CULTURAL LANDSCAPE

6.5

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Analyze the role of cultural landscape in political geography.

The world over, national politics is literally written on the landscape. State-driven initiatives for frontier settlement, economic development, and territorial control have profound effects on the landscape. Conversely, political writers and politicians look to landscape as a source of imagery to support or discredit political ideologies.

IMPRINT OF THE LEGAL CODE

Many laws affect the cultural landscape. Among the most noticeable are those that regulate the land-survey system because they often require that land be divided into specific geometric patterns. As a result, political boundaries can become highly visible (Figure 6.28). In Canada, for example, the laws of the French-speaking province of Québec encourage land survey in long, narrow parcels, but most English-speaking provinces, such as Ontario, use a rectangular system. Thus, the political border between Québec and Ontario can be spotted easily from the air.

257

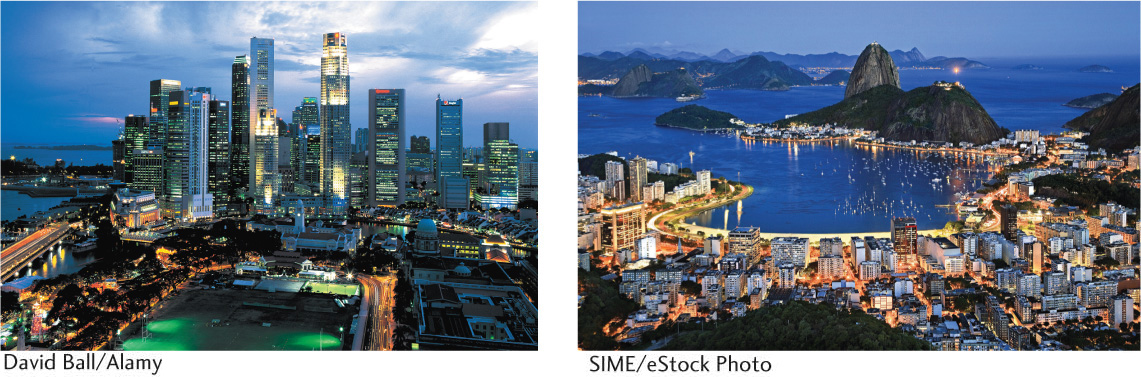

Legal imprints can also be seen in the cultural landscape of urban areas. In Rio de Janeiro, height restrictions on buildings have been enforced for a long time. The result is a waterfront lined with buildings of uniform height (Figure 6.29). By contrast, most American cities have no height restrictions, allowing skyscrapers to dominate the central city. The consequence is a jagged skyline for cities such as San Francisco or New York City. Many other cities around the world lack height restrictions, such as Malaysia’s Kuala Lumpur, which has the world’s tallest skyscrapers.

Perhaps the best example of how political philosophy and the legal code are written on the landscape is the so-called township and range system of the United States. The system is the brainchild of Thomas Jefferson—an early U.S. president and one of the authors of the U.S. Constitution—who chaired a national committee on land surveying that resulted in the U.S. Land Ordinance of 1785. Jefferson’s ideas for surveying, distributing, and settling the western frontier lands as they were cleared of Native Americans were based on a political philosophy of “agrarian democracy.” Jefferson believed that political democracy had to be founded on economic democracy, which in turn required a national pattern of equitable land-ownership by small-scale independent farmers. In order to achieve this agrarian democracy, the western lands would need to be surveyed into parcels that could then be sold at prices within reach of family farmers of modest means.

258

Jefferson’s solution was the township and range system, which established a grid of square-shaped “townships” with 6-mile (9.6-kilometer) sides across the Midwest and West. Each of these was then divided into 36 sections of 1 square mile (2.6 square kilometers), which were in turn divided into quarter-sections, and so on. Sections were to be the basic landholding unit for a class of independent farmers. Townships were to provide the structure for self-governing communities responsible for public schools, policing, and tax collection. With the exception of the 13 original colonies and a few other states or portions of states, a gridlike landscape was imposed on the entire country as a result of Jefferson’s political philosophy and accompanying land-survey system (Figure 6.30).

PHYSICAL PROPERTIES OF BOUNDARIES

Demarcated political boundaries can also be strikingly visible, forming border landscapes. Political borders are usually most visible where restrictions limit the movement of people between neighboring countries. Sometimes such boundaries are even lined with cleared strips, barriers, pillboxes, tank traps, and other obvious defensive installations. At the opposite end of the spectrum are international borders, such as that between Tanzania and Kenya in East Africa, that are unfortified, thinly policed, and in many places very nearly invisible. Even so, undefended borders of this type are usually marked by regularly spaced boundary pillars or cairns, customhouses, and guardhouses at crossing points (Figure 6.31).

Occasionally, present-day political boundaries reflect the durable landscape imprint of long-vanished cultures. Some of the best-known examples come from the ancient Roman Empire. In England, for example, many of today’s parish and township boundaries surrounding the city of Bath follow the property markers of ancient Roman villas. Probably the best known of the Roman landscape’s influence on present-day boundaries is Hadrian’s Wall in northern England. Named after a Roman Emperor, the wall was constructed as a fortification to defend against the unconquered peoples to the north. Today, Hadrian’s Wall parallels the modern border between England and Scotland (Figure 6.32).

THE IMPRESS OF CENTRAL AUTHORITY

Attempts to impose centralized government appear in many facets of the landscape. Railroad and highway patterns focused on the national core area, and radiating outward like the spokes of a wheel to reach the hinterlands of the country, provide good indicators of central authority. In Germany, the rail network developed largely before unification of the country in 1871. As a result, no focal point stands out. However, the superhighway system of autobahns, encouraged by Hitler as a symbol of national unity and power, tied the various parts of the Reich to such focal points as Berlin or the Ruhr industrial district.

The visibility of provincial borders within a country also reflects the central government’s strength and stability. Stable, secure countries, such as the United States, often permit considerable display of provincial borders. Displays aside, such borders are easily crossed. Most state boundaries in the United States are marked with signboards or other features announcing the crossing. By contrast, unstable countries, where separatism threatens national unity, often suppress such visible signs of provincial borders. Also in contrast, such “invisible” borders may be exceedingly difficult to cross when a separatist effort involves armed conflict.

259

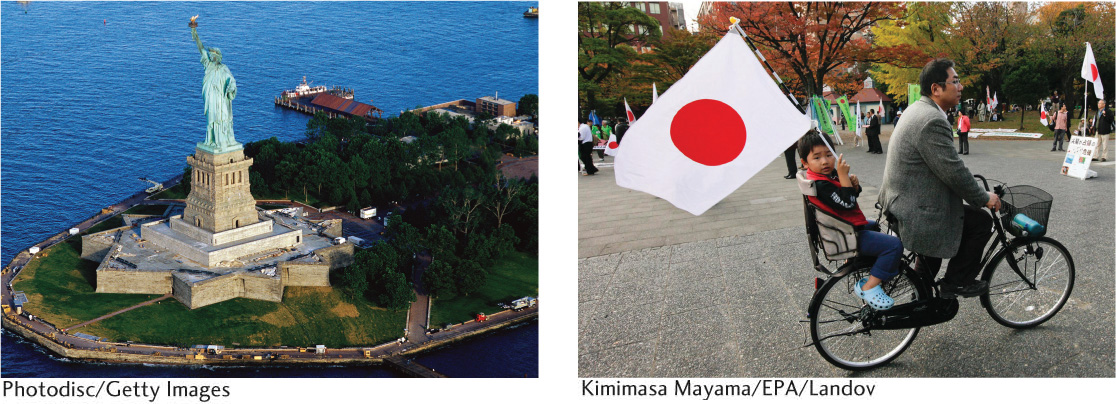

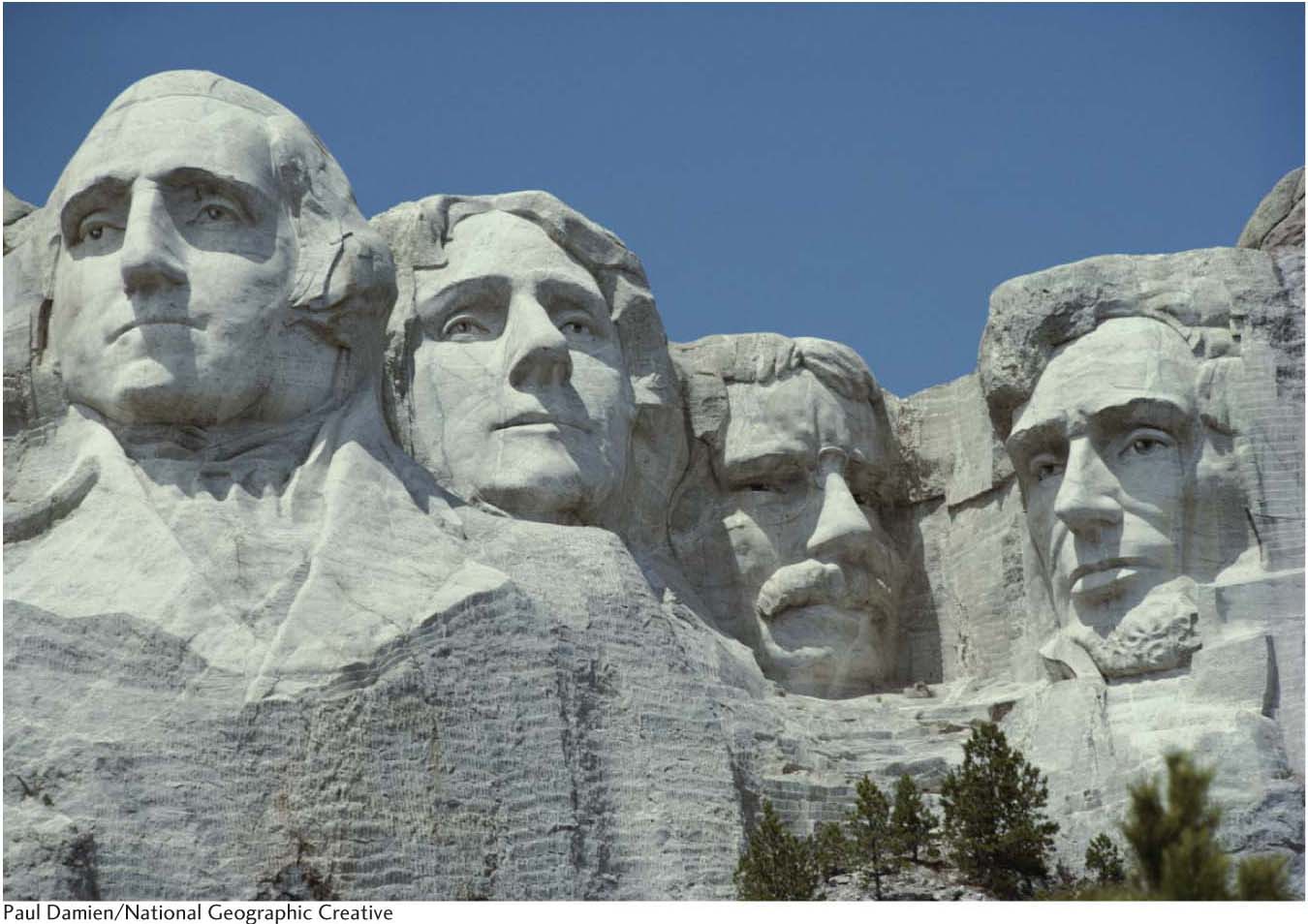

NATIONAL ICONOGRAPHY ON THE LANDSCAPE

The cultural landscape is rich in symbolism and visual metaphor, and political messages are often conveyed through such means. Statues of national heroes or heroines and of symbolic figures such as the goddess Liberty or Mother Russia form important parts of the political landscape, as do assorted monuments. The elaborate use of national colors can be visually very powerful as well. Landscape symbols such as the Rising Sun flag of Japan, the Statue of Liberty in New York Harbor, and the Latvian independence pillar in Riga (which stood untouched throughout half a century of Russian-Soviet rule) evoke deep patriotic emotions (Figure 6.33 and Figure 6.34). The sites of heroic (if often futile) resistance against invaders, as at Masada in Israel, prompt similar feelings of nationalism.

Some geographers theorize that the political iconography of landscape derives from an elite, dominant group in a country’s population and that its purpose is to legitimize or justify its power and control over an area. The dominant group seeks both to rally emotional support and to arouse fear in potential or real enemies. As a result, the iconographic political landscape is often controversial or contested, representing only one side of an issue. Look again at Figure 6.34. The area in which Mount Rushmore stands, the Black Hills, is sacred to the Native Americans who controlled the land before whites seized it. How might these Native Americans, the Lakota Sioux, perceive this monument? Are any other political biases contained in it? Cultural landscapes are always complicated and subject to differing interpretations and meanings, and political landscapes are no exception.

The landscapes of capital cities are important in shaping a sense of national identity and belonging. Geographer Diana Ter-Ghazaryan’s study of Armenia’s national capital, Yerevan, shows how central and contentious urban landscape design can be to national identity. After gaining independence from the Soviet Union, the Armenian political elite of the country began redesigning the capital city as part of a process of symbolically constructing a national identity for a modern, democratic Armenia. Ter-Ghazaryan identified three key sites that symbolically anchored the Yervan landscape: Opera Square, Northern Avenue, and Republic Square (Figure 6.35). The post-Soviet development of each of these sparked street protests over what Yerevan will become and what it means to be Armenian. National identity, especially in times of major political transition such as Armenia has experienced, can be a very contentious issue that is expressed through struggles over the physical landscape of a nation’s capital.

In a more contemporary study, geographer Gail Hollander has demonstrated the important symbolic role that the landscape and environment of the Florida Everglades have played in U.S. presidential elections (Figure 6.36). The symbolic role of the Everglades changed over time, from the 1928 presidential campaign to the present. In 1928 it was presented as worthless swampland. As such, it played a key role in the election of President Herbert Hoover, who promised to drain it for agricultural development. By the 1970s, it was seen as an endangered wetland in need of protection and ecological restoration. Thus, in virtually every present-day presidential campaign, the candidates’ positions on the Everglades are seen as indicators of their commitment to the environment. Photo opportunities in the park give both Democratic and Republican candidates alike a chance to symbolically link their political campaigns to the ecological restoration of what has come to be viewed as a national treasure.

260

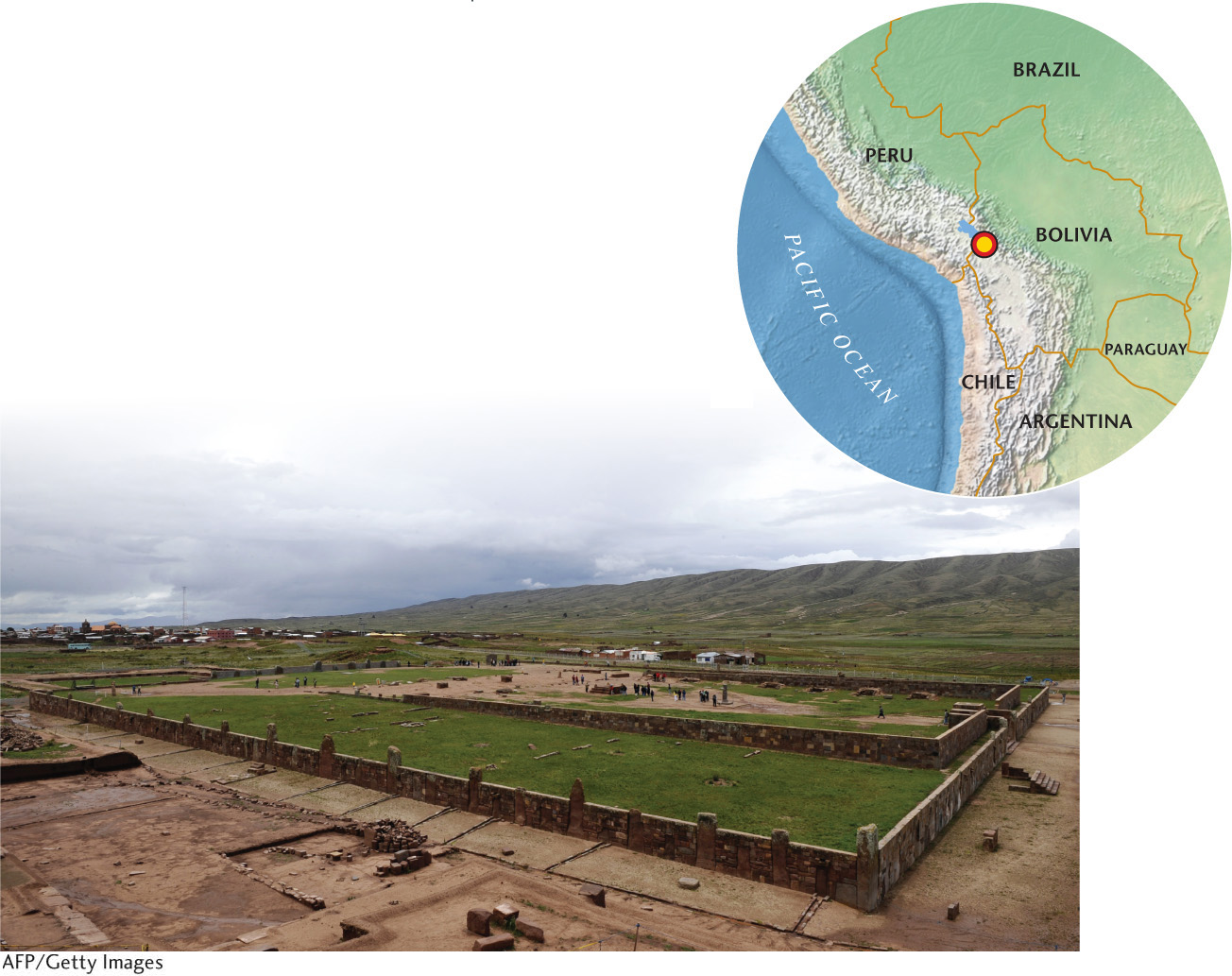

World Heritage Site: Tiwanaku: Spiritual and Political Center of the Tiwanaku Culture

World Heritage Site

Tiwanaku: Spiritual and Political Center of the Tiwanaku Culture

Tiwanaku is an ancient example of how cultural landscapes can reflect and reinforce centralized political authority. Inscribed by UNESCO in 2000, Tiwanaku served as the political and religious center of an empire that dominated the Altiplano region of the Andes Mountains between 400 and 900 c.e. It retains political geographic significance today as a symbol of Bolivian national identity.

◼ Tiwanaku was a sprawling planned city of 70,000 to 125,000 residents located near the southern shores of Lake Titicaca in Bolivia. Its ruins provide an exceptional example of pre-Incan civic architecture. The architecture and city layout symbolically reflect the site’s former role as an imperial center.

◼ Surrounding the imperial center were the towns and villages colonized by the Tiwanaku rulers. Even further out were the settlements that the center dominated, but did not colonize or conquer militarily. All of the areas were knitted together economically and politically by a network of alpaca caravan trade routes that stretched across the Altiplano and beyond. The central authority at Tiwanaku controlled the caravans.

◼ The Tiwanaku rulers developed an ideological and religious iconography (visual images and symbols used in art) that was embedded in the center’s architecture and then reproduced in the material life of the far-flung regions under its influence. For example, iconography originating from the center appeared on ceramic vessels and was reproduced on stone markers placed in peripheral settlements. Conversely, the rulers incorporated the iconography of the periphery into public architecture of the central city, thereby encouraging a variety of distant ethnic communities to identify themselves as part of a larger state. Thus, the symbolism embedded in civic architecture reinforces the idea of a periphery politically, culturally, and economically linked together through the center.

261

ANCIENT CIVIC ARCHITECTURE: Much of the ancient city has been erased by modern development, but the ruins of the monumental stone buildings in the ceremonial center remain protected. The architecture of the center, which is oriented toward the cardinal points, reflects both the complexity of the Tiwanaku Empire’s political structure as well as its religious nature.

◼ Tiwanaku culture perfected stone cutting, carving, and polishing and used those skills to create a monumental architecture as a projection of its power. A series of architectural structures—Kalasasaya’s Temple, Akapana’s Pyramid, and Pumapumku’s Pyramid—define the space of the center.

◼ Akapana’s Pyramid, originally rising over 18 meters, is the most commanding of the structures. Though since destroyed, a temple stood at the top, as is also common in Mesoamerican architecture.

◼ Kalasasaya’s Temple is a rectangular structure that likely functioned as an observatory. In its interior are two carved monoliths as well as the Gate of the Sun, a monumental sculpture standing 3 meters tall, 4 meters wide, and carved from a single stone. Multiple human and anthropomorphic animal carvings decorate the Gate of the Sun, with what is likely a major deity appearing at the top of the monument, at its center. Some archeologists suggest that the carvings on the gate constituted an agricultural calendar.

◼ Other architectural features in the ancient city include the Palace of Putuni and Kantatillita, which stands in tribute to the political and administrative authority of imperial rule.

TOURISM: Located only 70 kilometers west of La Paz, Bolivia, and served by public transportation, Tiwanaku is relatively accessible.

◼ Popular literature in the United States and Europe speculated (wrongly) that the site provides evidence that an advanced race of extraterrestrials once visited Earth. This notoriety has been a major draw for international tourists, particularly during astronomical events.

◼ Sometimes referred to as the “American Stonehenge,” thousands of visitors gather during the southern hemisphere’s winter solstice for a dawn ritual.

◼ Visitation has sparked a local tourist industry that has become the most important source of income in surrounding communities.

◼ Located near the southern shores of Lake Titicaca in Bolivia.

◼ Tiwanaku craftspeople perfected stone cutting, carving, and polishing, creating a monumental architecture as a projection of the center’s political power.

◼ Kalasasaya’s Temple, Akapana’s Pyramid, and Pumapumku’s Pyramid define the space of the center.

262

263