REGION

8.1

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Explain the connection between region and agriculture.

For thousands of years, farmers have found ways to cope with a range of environmental conditions, creating in the process an array of different types of food-producing systems. Collectively, these farming practices have constructed formal agricultural regions.

agricultural region

A geographic region defined by a distinctive combination of physical and environmental conditions; crop type; settlement patterns; and labor, cultivation, and harvesting practices.

318

During the past 500 years, colonialism, industrialization, and globalization have greatly altered existing practices and created new types of agricultural regions, such as plantations. One prominent trend over the past five centuries is the progressive, worldwide movement from extensive to intensive cultivation and husbandry. Extensive agriculture refers to the practices of farming and livestock raising that require low levels of labor and capital relative to the areal extent of land under production. Thus, extensive agriculture relies mostly on natural soil fertility and prevailing climate conditions. In contrast, intensive agriculture uses high levels of labor and capital relative to the size of the land holding. Increasingly, intensive agriculture overcomes local environmental constraints through irrigation; land reclamation; and the use of synthetic fertilizers, chemical pesticides and herbicides, and genetic engineering. Consequently, in order to understand agricultural regions, we need to consider the role of the environment, cultural factors, and the political and economic forces that influence a region.

extensive agriculture

The practices of farming and livestock raising using low levels of labor and capital relative to the areal extent of land under production, relying chiefly on natural soil fertility and prevailing climate.

intensive agriculture

The practices of farming and livestock raising using high levels of labor and capital relative to the size of the land holding, thus overcoming environmental constraints through irrigation, land reclamation, synthetic fertilizers, chemical pesticides and herbicides, and genetic engineering.

SWIDDEN CULTIVATION

Many of the peoples of tropical lowlands and hills in the Americas, Africa, and Southeast Asia practice a land-rotation agricultural system known as swidden cultivation. The term swidden is derived from an old English term meaning “burned clearing.” Using machetes, axes, and chainsaws, swidden cultivators chop away the undergrowth from small patches of land and kill the trees by removing a strip of bark completely around the trunk. After the dead vegetation dries out, the farmers set it on fire to clear the land. Because of these clearing techniques, swidden cultivation is also called slash-and-burn agriculture. Working with digging sticks or hoes, the farmers then plant a variety of crops in the ash-covered clearings, varying from the maize (corn), beans, bananas, and manioc of the Americas to the yams and non-irrigated rice grown in Southeast Asia (Figure 8.1). Different crops typically share the same clearing, a practice called intercropping. This technique allows taller, stronger crops to shelter lower, more fragile ones; reduces the chance of total crop losses from disease or pests; and provides the farmer with a varied diet. The complexity of many intercropping systems reveals the depth of knowledge acquired by swidden cultivators over many centuries. Relatively little tending of the plants is necessary until harvest time, and no fertilizer is applied to the fields because the ashes from the fire are a sufficient source of nutrients.

swidden cultivation

A type of agriculture characterized by land rotation in which temporary clearings are used for several years and then abandoned to be replaced by new clearings; also known as slash-and-burn agriculture.

intercropping

The practice of growing two or more different types of crops in the same field at the same time.

319

The planting and harvesting cycle is repeated in the same clearings for perhaps three to five years, until soil fertility begins to decline as nutrients are taken up by crops and not replaced. Subsequently, crop yields decline. These fields then are temporarily left fallow, and new clearings are prepared to replace them. Because the farmers periodically shift their cultivation plots, another commonly used term for the system is shifting cultivation. The abandoned cropland lies fallow for 10 to 20 years before farmers return to clear it and start the cycle again. Swidden cultivation represents one form of subsistence agriculture: food production mainly for the family and local community rather than for market.

subsistence agriculture

Farming to supply the minimum food and materials necessary to survive.

Although the technology of swidden may be simple, it has proved to be an efficient and adaptive strategy. Swidden farming, unlike some modern systems, is ecologically sustainable and has endured for millennia. Indeed, contemporary studies suggest that some swidden systems have actually enhanced biodiversity. Furthermore, swidden returns more calories of food for the calories spent on cultivation than does modern mechanized agriculture. In many tropical forest regions, swidden cultivation, unlike Western plantations, has left most of the forest intact over centuries of continuous use.

Nonetheless, swidden cultivation can be environmentally destructive under certain conditions. In poor countries with large landless populations, one often finds a front of pioneer swidden farmers advancing on the forests. In such situations, a range of institutional, economic, political, and demographic factors restrict poor farmers’ abilities to employ the methods of swidden agriculture in a sustainable way. In many tropical countries, for example, a small proportion of the population owns most of the best agricultural land, forcing the majority of farmers to clear forests to gain access to land. Another condition that may diminish the sustainability of swidden cultivation occurs when a population experiences a sudden increase in its rate of growth and political or social conditions restrict its mobility. Swidden cultivation, still widely practiced throughout the tropics, is thus a highly variable system, occurring in both sustainable and unsustainable forms.

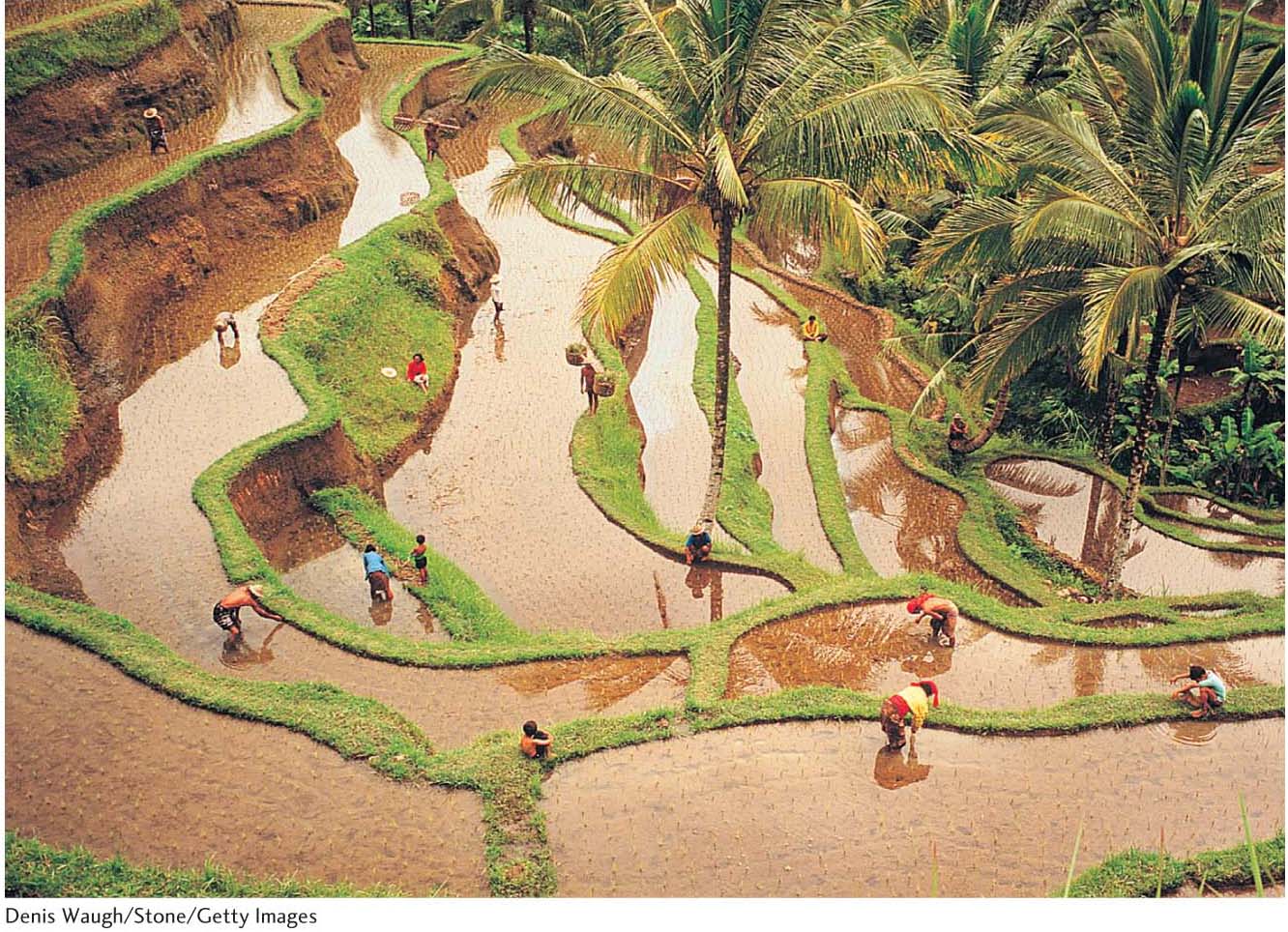

PADDY RICE FARMING

Peasant farmers in the humid tropical and subtropical parts of Asia practice a highly distinctive type of agriculture called paddy rice farming. Rice, the dominant paddy crop, forms the basis of civilizations in which almost all the caloric intake is of plant origin. From the monsoon coasts of India through the hills of southeastern China and on to the warmer parts of Korea and Japan stretches a broad region of diked, flooded rice fields, or paddies, many of which are perched on terraced hillsides (Figure 8.2). The terraced paddy fields form a striking cultural landscape (see Figure 1.15).

paddy rice farming

The cultivation of rice on a paddy, or small flooded field enclosed by mud dikes, practiced in the humid areas of the Far East.

A paddy rice farm of only 3 acres (1 hectare = 2.47 acres) is usually adequate to support a family because irrigated rice provides a very large output of food per unit of land. Still, paddy farmers must till their small patches intensively to harvest enough food. A system of irrigation that can deliver water when and where it is needed is key to success. In addition, large amounts of fertilizer must be applied to the land. Paddy farmers often plant and harvest the same parcel of land twice per year, a practice known as double-cropping. These systems are extremely productive, yielding more food per acre than many forms of industrialized agriculture in the United States.

double-cropping

Harvesting twice a year from the same parcel of land.

320

The modern era has witnessed a restructuring of paddy rice farming in more developed countries, such as Japan, Korea, and Taiwan. In some cases, the terrace structure has been reengineered to produce larger fields that can be worked with machines. In addition, dams, electric pumps, and reservoirs now provide a more reliable water supply, and high-yielding seeds, pesticides, and synthetic fertilizers boost production further. Most paddy rice farmers now produce mainly for urban markets.

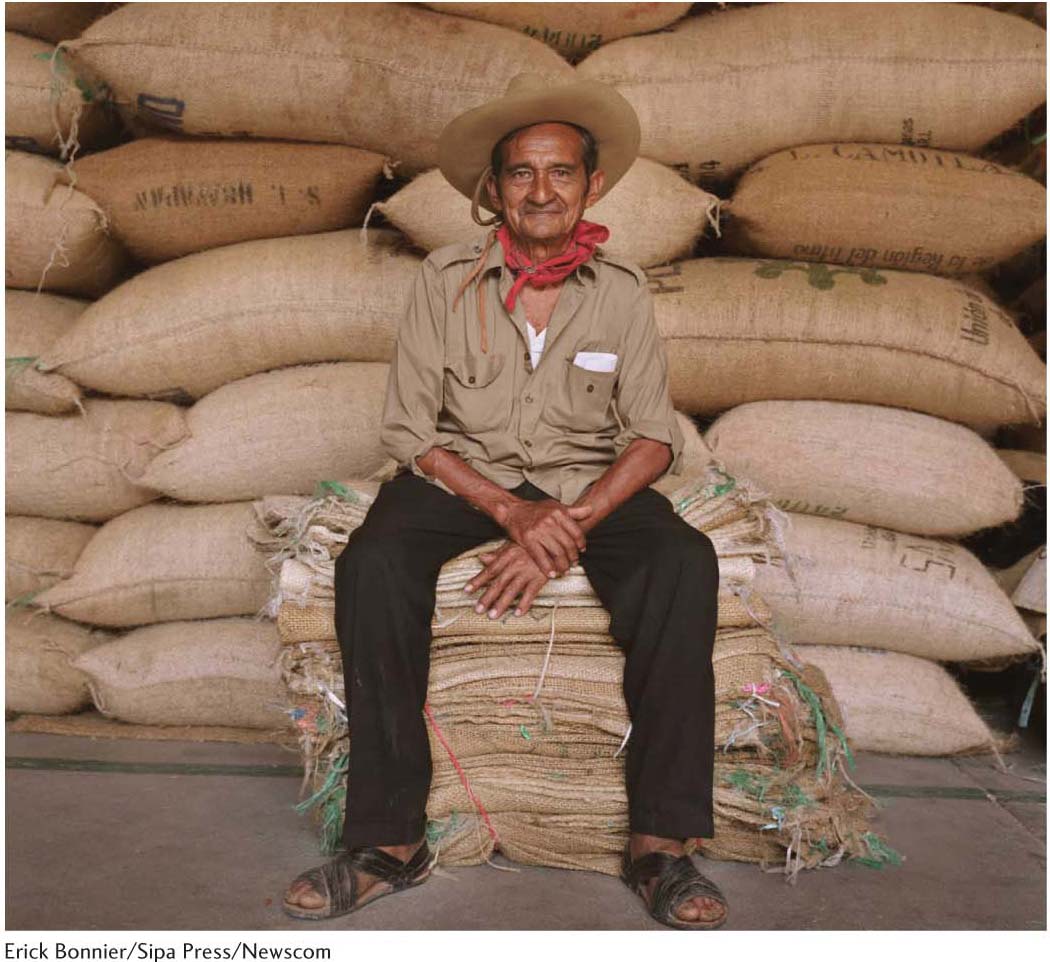

PEASANT GRAIN, ROOT, AND LIVESTOCK FARMING

In colder, drier Asian farming regions that are climatically unsuited to paddy rice farming—as well as in the river valleys of the Middle East, in parts of Europe, in Africa, and in the mountain highlands of Latin America and New Guinea—farmers practice a diverse system of agriculture based on bread grains, root crops, and herd livestock (Figure 8.3). Many geographers refer to these farmers as peasants, recognizing that they often represent a distinctive folk culture and socioeconomic class strongly rooted in the land. Peasants are small-scale farmers who own their fields, rely chiefly on family labor, and produce both for their own subsistence and for sale in the market. The dominant grain crops in these regions are wheat, barley, sorghum, millet, oats, and maize. Common cash crops— some of them raised for export— include cotton, flax, hemp, coffee, and tobacco (Figure 8.4).

peasant

Small-scale farmers who own their fields, rely chiefly on family labor, and produce both for their own subsistence and for sale in the market.

folk culture

A small, cohesive, stable, isolated, nearly self-sufficient group that is homogenous in custom and race; characterized by a strong family or clan structure, order maintained through sanctions based on religion or family, little division of labor other than between the sexes, frequent and strong interpersonal relationships, and a material culture consisting mainly of handmade goods.

These farmers also raise herds of cattle, pigs, sheep, and, in South America, llamas and alpacas. The livestock pull the plow; provide milk, meat, and wool; serve as beasts of burden; and produce manure for the fields. They also consume a portion of the grain harvest. In some areas, such as the Middle Eastern river valleys, the use of irrigation helps support this peasant system. In general, however, most modern agricultural technologies are beyond the financial reach of most peasants.

321

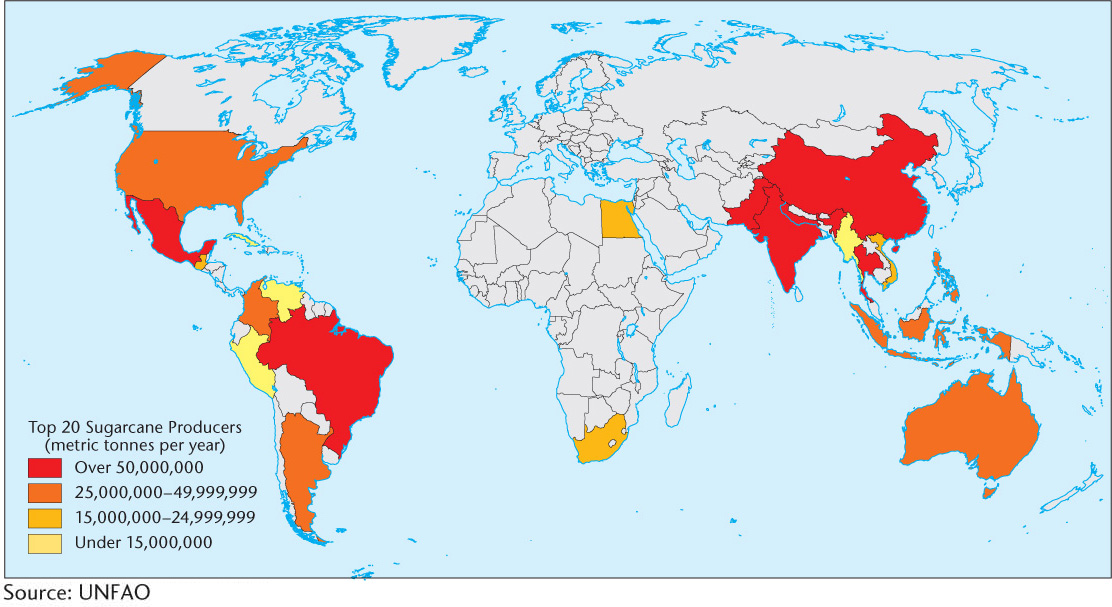

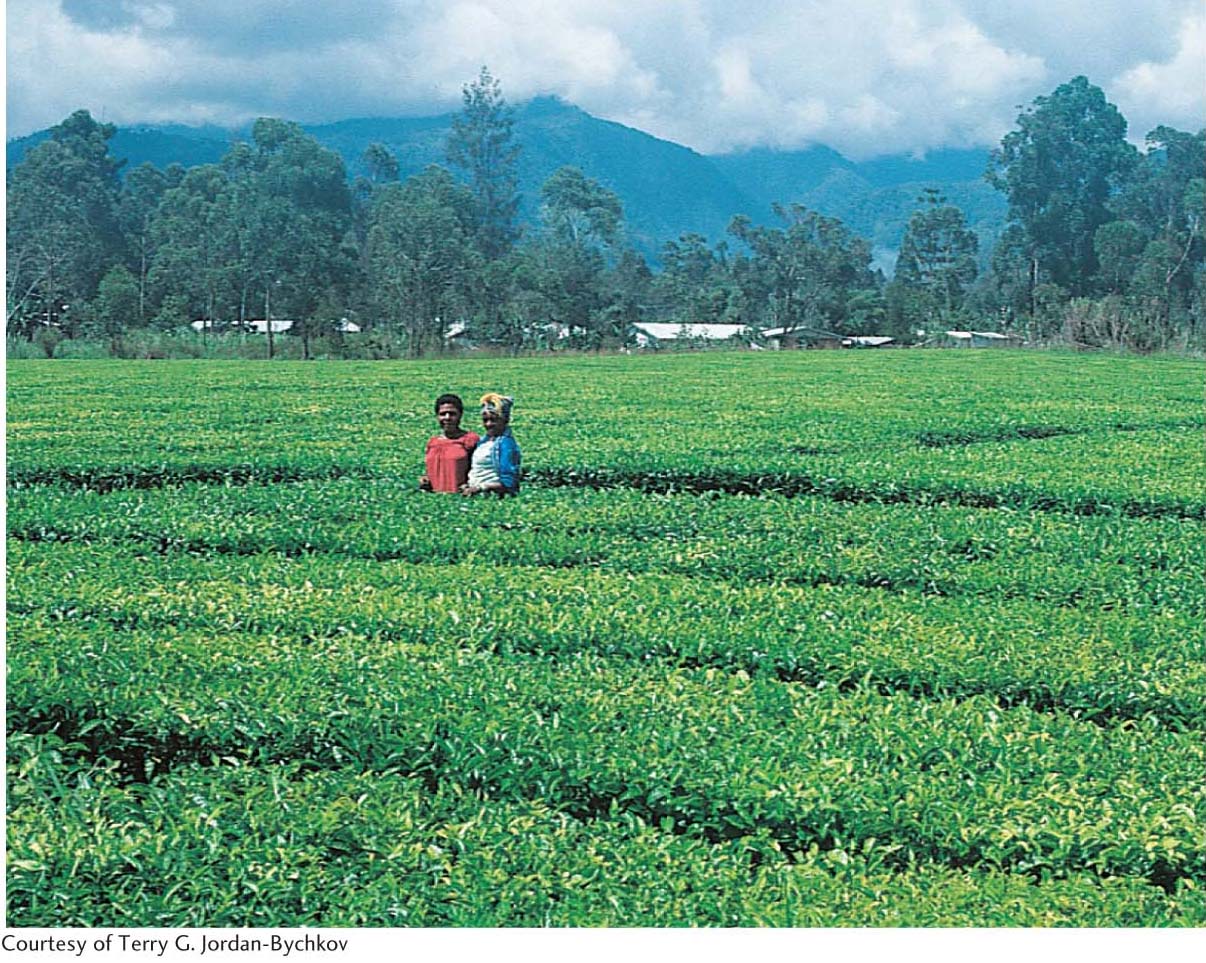

PLANTATION AGRICULTURE

In certain tropical and subtropical areas, Europeans and Americans introduced a commercial agricultural system called plantation agriculture. A plantation is a landholding devoted to capital-intensive, large-scale, specialized production of one tropical or subtropical crop for the global market. Each plantation district in the tropical and subtropical zones tends to specialize in one crop. Plantation agriculture has long relied on large amounts of manual labor, initially in the form of slave labor and later as wage labor. The plantation system originated in the 1400s on Portuguese-owned sugarcane-producing islands off the coast of tropical West Africa—Säo Tomé and Principe—but the greatest concentrations now exist in the American tropics, Southeast Asia, and tropical South Asia (Figure 8.5). Historically, most plantations have been located near the seacoast, close to the shipping lanes that carry their produce to nontropical lands such as Europe, the United States, and Japan.

plantation agriculture

A system of monoculture for producing export crops requiring relatively large amounts of land and capital; originally dependent on slave labor.

plantation

A large landholding devoted to specialized production of a tropical cash crop.

Workers usually live right on the plantation, where a rigid social and economic segregation of labor and management produces a two-class society of the wealthy and the poor. As a result of the concentration of ownership and production, a handful of multinational corporations, such as Chiquita and Dole, control the largest share of plantations globally. Tension between labor and management is not uncommon, and the societal ills of the plantation system remain far from cured (Figure 8.6).

322

Plantations provided the base for European and American economic expansion into tropical Asia, Africa, and Latin America. They maximize the production of luxury crops for Europeans and Americans, such as sugarcane, bananas, coffee, coconuts, spices, tea, cacao, pineapples, rubber, and tobacco (Figure 8.7). Similarly, textile factories require cotton, sisal, jute, hemp, and other fiber crops from the plantation areas. Much of the profit from these plantations is exported, along with the crops themselves, to Europe and North America, another source of political friction between countries of the global North and South.

MARKET GARDENING

The growth of urban markets in the last few centuries also gave rise to other commercial forms of agriculture, including market gardening, also known as truck farming. Unlike plantations, truck farms are located in developed countries and specialize in intensively cultivated nontropical fruits, vegetables, and vines. They raise no livestock. Many districts concentrate on a single product, such as wine, table grapes, raisins, olives, oranges, apples, lettuce, or potatoes, and the entire farm output is raised for sale rather than for consumption on the farm (Figure 8.8). Many truck farmers participate in cooperative marketing arrangements and depend on migratory seasonal farm laborers to harvest their crops. Market garden districts appear in most industrialized countries. In the United States, a broken belt of market gardens extends from California eastward through the Gulf and Atlantic coast states, with scattered districts in other parts of the country. The lands around the Mediterranean Sea are dominated by market gardens. In regions with mild climates, such as California, Florida, and the Mediterranean region, winter vegetables are a common market crop raised for sale in colder regions of the higher latitudes.

market gardening

Farming devoted to specialized fruit, vegetable, or vine crops for sale rather than consumption.

323

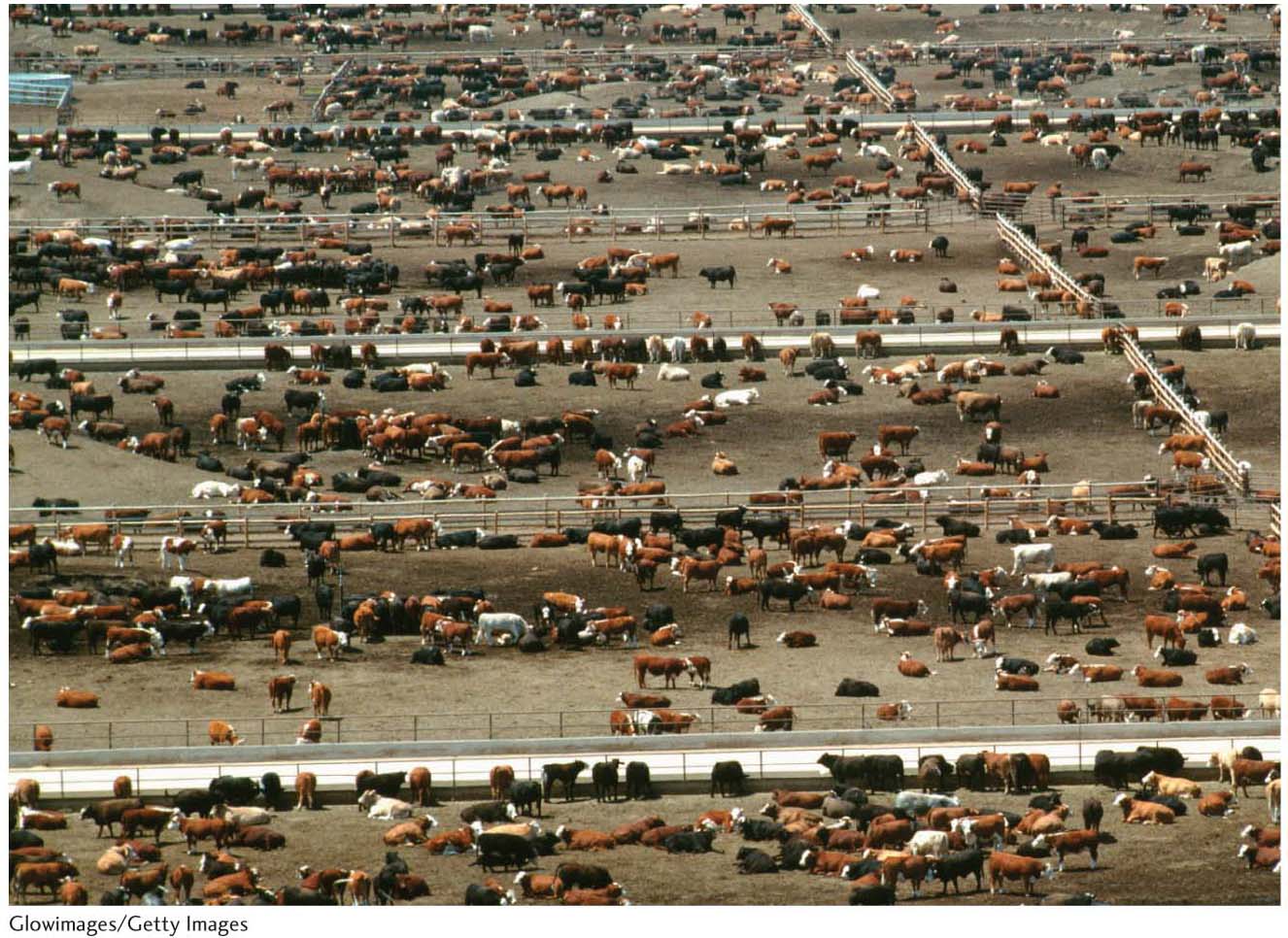

LIVESTOCK FATTENING

In livestock fattening, farmers raise and fatten cattle and hogs for slaughter. One of the most highly developed fattening are as is the famous Corn Belt of the U.S. Midwest, where farmers raise corn and soybeans to feed cattle and hogs. Typically, slaughterhouses are located close to feedlots, creating a new meat-producing region, which is often dependent on mobile populations of cheap immigrant labor. A similar system prevails over much of western and central Europe, though the feed crops there more commonly are oats and potatoes. Other zones of commercial livestock fattening appear in overseas European settlement zones such as southern Brazil and South Africa.

livestock fattening

A commercial type of agriculture that produces fattened cattle and hogs for meat.

One of the central traditional characteristics of livestock fattening is the combination of crops and animal husbandry. Farmers breed many of the animals they fatten, especially hogs. In the last half of the twentieth century, livestock fatteners began to specialize their activities; some concentrated on breeding animals, others on preparing them for market. In the factorylike feedlot, farmers raise imported cattle and hogs on purchased feed (Figure 8.9). Increases in the amount of land and crop harvest dedicated to beef production have accompanied the growth in feedlot size and number. In the United States, across Europe, and in European settlement zones around the globe, 51 to 75 percent of all grain raised goes to livestock fattening.

feedlot

A factorylike farm devoted to either livestock fattening or dairying; all feed is imported and no crops are grown on the farm.

The livestock fattening and slaughtering industry has become increasingly concentrated, on both the national and global scales. In 1980 in the United States, the top four companies accounted for 41 percent of all slaughtered cattle. By 2000 the top four companies were slaughtering 81 percent of all feedlot cattle. One company alone accounted for 35 percent. Corporate conglomerates such as ConAgra and Cargill control much of the beef supply through their domination of the grain market and ownership of feedlots and slaughterhouses. The concentration of the industry has extended north and south across the border, primarily spurred by the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Cargill owns beef operations in more than 60 countries. One industry observer concludes that three multinational companies control the entire global beef industry.

324

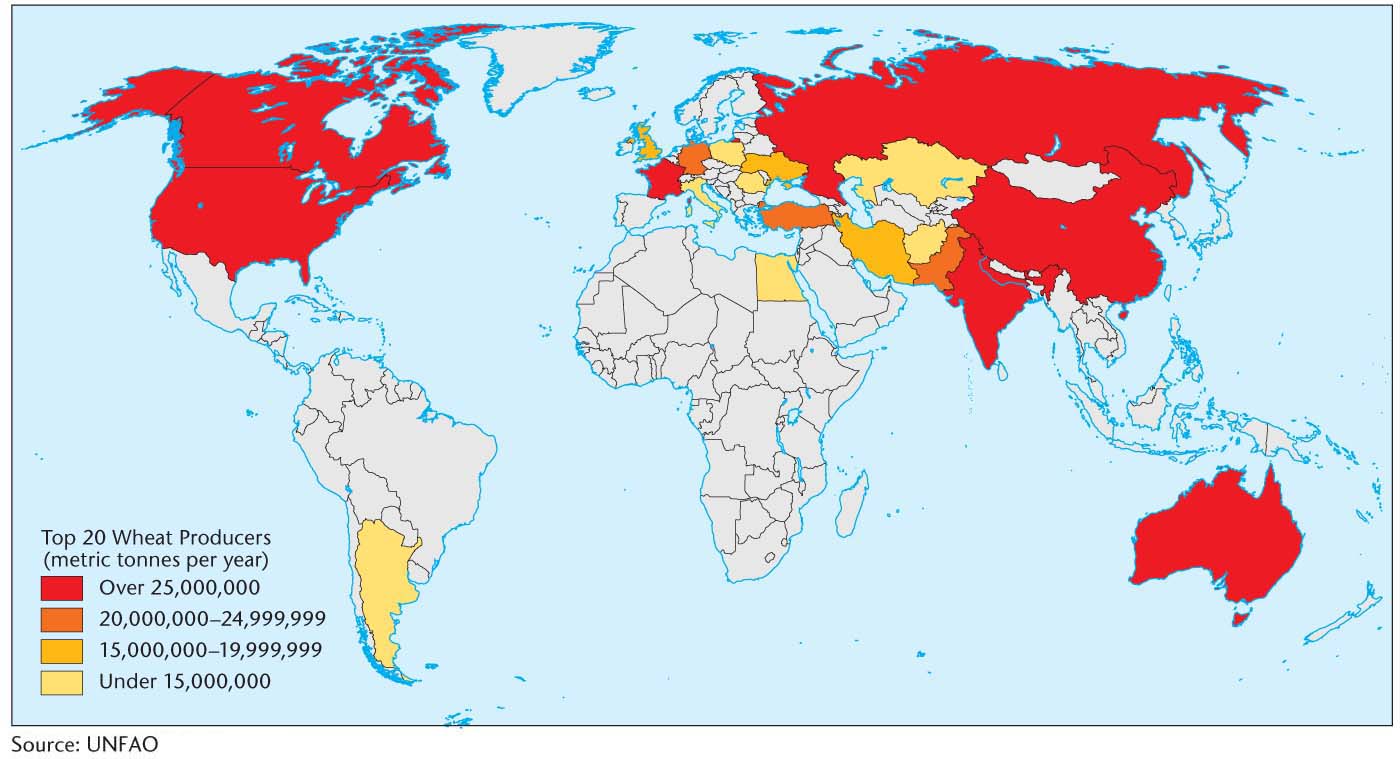

GRAIN FARMING

Grain farming is a type of specialized agriculture in which farmers grow primarily wheat, rice, or corn for commercial markets. The United States is the world’s leading wheat and corn exporter. The United States, Canada, Australia, the European Union (EU), and Argentina together account for more than 85 percent of all wheat exports, while the United States alone accounts for about 70 percent of world corn exports (Figure 8.10). Wheat belts stretch through Australia, the Great Plains of interior North America, the steppes of Russia and Ukraine, and the pampas of Argentina. Farms in these areas generally are very large, ranging from family-run wheat farms to giant corporate operations (Figure 8.11).

Widespread use of machinery, synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, and genetically engineered seed varieties enables grain farmers to operate on this large scale. The planting and harvesting of grain are more completely mechanized than any other form of agriculture. Commercial rice farmers employ such techniques as sowing grain from airplanes. Harvesting is usually done by hired migratory crews operating corporation-owned machines (Figure 8.12). Perhaps grain farming’s ultimate development is the suitcase farm, found in the Wheat Belt of the northern Great Plains of the United States. The people who own and operate these farms do not live on the land. Most of them own several suitcase farms, lined up in a south-to-north row through the Plains states. They keep fleets of farm machinery, which they send north with crews of laborers along the string of suitcase farms to plant, fertilize, and harvest the wheat. The progressively later ripening of the grain as one moves north allows these farmers to maintain and harvest crops on all their farms with the same crew and the same machinery. Except for visits by migratory crews, the suitcase farms are uninhabited.

suitcase farm

In American commercial grain agriculture, a farm on which no one lives; planting and harvesting are done by hired migratory crews.

325

Such highly mechanized, absentee-owned, large-scale operations, or agribusinesses, have mostly replaced the small, husband- and wife-operated American family farm, an important part of the U.S. rural heritage. Geographer Ingolf Vogeler documented the decline of small family farms in the American countryside and argued that U.S. governmental policies, prompted by the forces of globalization, have consistently favored the interests of agribusiness, thereby hastening this decline. Family-owned farms continue to play an important role, but they now operate mostly as large agribusinesses that own or lease many far-flung grain fields.

DAIRYING

In many ways, the specialized production of dairy goods closely resembles livestock fattening. In the large dairy belts of the northern United States from New England to the upper Midwest, western and northern Europe, southeastern Australia, and northern New Zealand, the keeping of dairy cows depends on the large-scale use of pastures. In colder areas, some acreage must be devoted to winter feed crops, especially hay. Dairy products vary from region to region, depending, in part, on how close the farmers are to their markets. Dairy belts near large urban centers usually produce milk, which is more perishable, while those farther away specialize in butter, cheese, or processed milk. An extreme case is New Zealand, which, because of its remote location from world markets, produces much butter.

326

As with livestock fattening, in recent decades a rapidly increasing number of dairy farmers have adopted the feedlot system and now raise their cattle on feed purchased from other sources. Often situated on the suburban fringes of large cities for quick access to market, the dairy feedlots operate like factories. Like industrial factory owners, feedlot dairy owners rely on hired laborers to help maintain their herds. Dairy feedlots are another indicator of the rise of globalization-induced agribusiness and the decline of the family farm. By easing trade barriers, globalization compels U.S. dairy farmers to compete with producers in other parts of the world. Huge feedlots, a factory-style organization of production, automation, the concentration of ownership, and the increasing size of dairy farms are responses to this intense competition.

NOMADIC HERDING

In the dry or cold lands of the Eastern Hemisphere, particularly in the deserts, prairies, and savannas of Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, and the interior of Eurasia, nomadic livestock herders graze cattle, sheep, goats, and camels. North of the tree line in Eurasia, the cold tundra forms a zone of nomadic herders who raise reindeer. The common characteristic of all nomadic herding is mobility. Herders move with their livestock in search of forage for the animals as seasons and range conditions change. Some nomads migrate from lowlands in winter to mountains in summer; others shift from desert areas during the rainy season to adjacent semiarid plains in the dry season or from tundra in summer to nearby forests in winter. Some nomads herd while mounted on horses, such as the Mongols of East Asia, or on camels, such as the Bedouin of the Arabian Peninsula. Others, such as the Rendile of East Africa, herd cattle, goats, and sheep on foot.

nomadic livestock herder

A member of a group that continually moves with its livestock in search of forage for its animals.

Their need for mobility dictates that the nomads’ few material possessions be portable, including the tents used for housing (Figure 8.13). Their mobile lifestyle also affects how wealth is measured. Typically, in nomadic cultures, wealth is based on the size of livestock holdings rather than on the accumulation of property and personal possessions. Usually, the nomads obtain nearly all of life’s necessities from livestock products or by bartering with the farmers of adjacent river valleys and oases.

For a number of different reasons, nomadic herding has been in decline since the early twentieth century. Some national governments established policies encouraging nomads to practice sedentary cultivation of the land. This practice was begun in the nineteenth century by British and French colonial administrators in North Africa because it allowed greater control of the people by the central governments. Today, many nomads are voluntarily abandoning their traditional life to seek jobs in urban areas or in the Middle Eastern oil fields. Recent severe drought in sub-Saharan Africa’s Sahel region, which decimated nomadic livestock herds, was a further impetus to abandon nomadic life.

sedentary cultivation

Farming in fixed and permanent fields.

327

In recent decades, research conducted by geographers and anthropologists in Africa’s semiarid environments has revealed the sound logic of nomadic herding practices. These studies demonstrate that nomadic cultures’ pasture and livestock management strategies are rational responses to an erratic and unpredictable environment. Rainfall is highly irregular in time and space, and herding practices must adjust. The most important nomadic strategy is mobility, which allows herders to take fullest advantage of the resulting variations in range productivity. These findings have led to a new appreciation of nomadic herding cultures and may cause governments to reconsider sedentarization programs, thus postponing the demise of herding cultures.

LIVESTOCK RANCHING

Superficially, ranching might seem similar to nomadic herding. It is, however, a fundamentally different livestock-raising system. Although both nomadic herders and livestock ranchers specialize in animal husbandry to the exclusion of crop raising and both live in arid or semiarid regions, livestock ranchers have fixed places of residence and operate as individuals rather than within a communal or tribal organization. In addition, ranchers raise livestock on a large scale for market, not for their own subsistence.

ranching

The commercial raising of herd livestock on a large landholding.

Livestock ranchers are found worldwide in areas with environmental conditions that are too harsh for crop production. They raise only two kinds of animals in large numbers: cattle and sheep. Ranchers in the United States, Canada, tropical and subtropical Latin America, and the warmer parts of Australia specialize in cattle raising. Midlatitude ranchers in cooler and wetter climates specialize in sheep. Sheep production is geographically concentrated to such a degree that only three countries—Australia, China, and New Zealand—account for 56 percent of the world’s export wool.

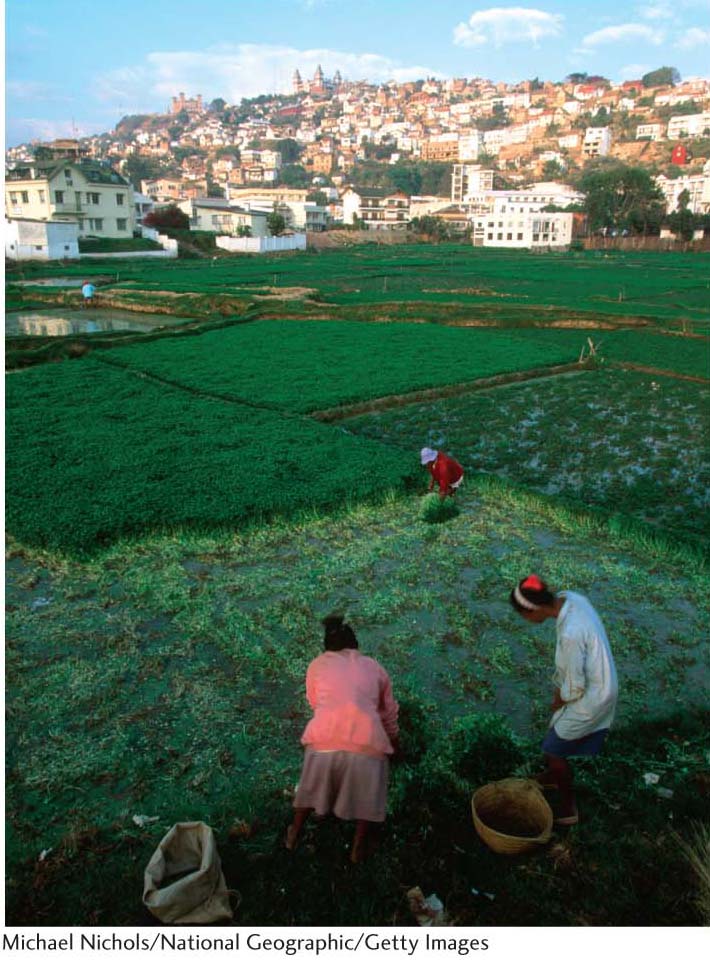

URBAN AGRICULTURE

The United Nations (UN) calculated that in 2008 the human species passed a milestone. For the first time in history, more people live in cities than in the countryside. As this global-scale rural-to-urban migration gained momentum, a distinct form of agriculture rose in significance. We might best call this urban agriculture. Millions of city dwellers, especially in Third World countries, now produce enough vegetables, fruit, meat, and milk from tiny urban or suburban plots to provide most of their food, often with a surplus to sell (Figure 8.14). In China, urban agriculture now provides 90 percent or more of all the vegetables consumed in the cities. In the African metropolises of Kampala and Dar es Salaam, 70 percent of the poultry and 90 percent of the leafy vegetables consumed in the cities, respectively, come from urban lands. In 2010 the UN Food and Agriculture Organization convened the first symposium on urban agriculture in Africa in recognition of the important role it will play in feeding the continent’s twenty-first-century urban residents.

urban agriculture

The raising of food, including fruit, vegetables, meat, and milk, inside cities, especially common in the Third World.

Geographer Susanne Freidberg has conducted research demonstrating the importance of urban agriculture to family income and food security in West Africa. Focusing on the city of Bobo-Dioulasso in Burkina Faso, Freidberg showed that though plots were small, urban agriculture offered residents “a culturally meaningful way to fulfill their roles as food producers and family providers.” In its heyday in the 1970s and 1980s, urban farming provided substantial incomes from vegetable sales in both the domestic and export markets. Since then, collapsing demand and the deterioration of environmental conditions have threatened the enterprise and undermined cooperation and trust within Bobo-Dioulasso’s urban agricultural communities.

328

In the developed world, urban agriculture is becoming more prevalent despite, or perhaps in reaction to, the fact that food sourcing is increasingly globalized. The reasons for the boom in urban agriculture in cities such as Vancouver, Canada, and London are complex. However, almost everywhere it is seen as a partial solution to the problems of food insecurity and lack of access to nutritious foods in cities. The work of geographer Nik Heynen has shown that solving food insecurity is integral to improving urban social justice in the United States. It tends to be poorer residents, often members of marginalized minority groups, who lack access to a healthy diet. Similarly in Europe, the World Health Organization (WHO) has identified the poor availability of and inequitable access to nutritious vegetables and fruits in cities, especially for vulnerable groups, as a major twenty-first-century problem for the region. According to the WHO, the promotion of local food production in European cities will aid in reducing urban poverty and inequalities.

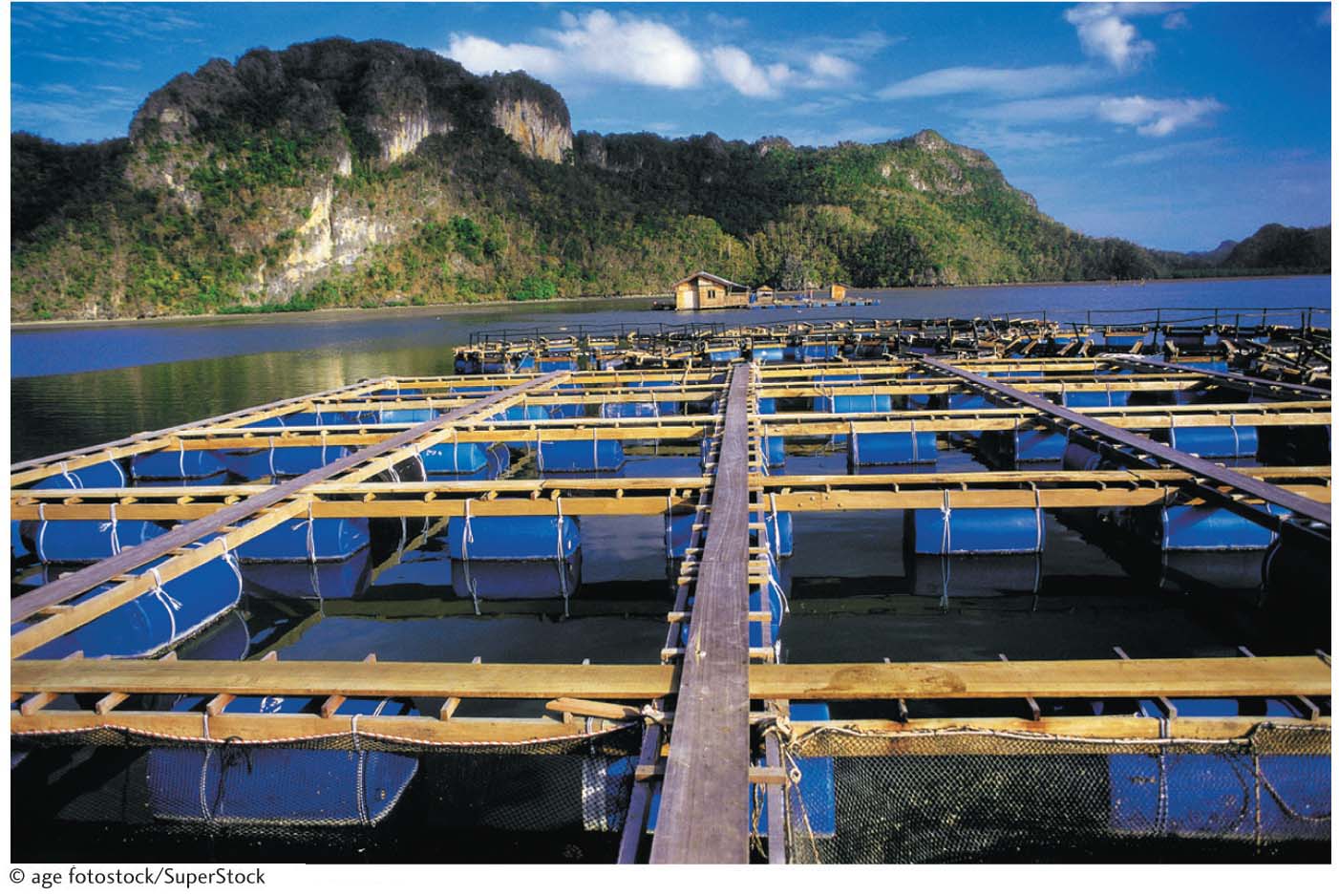

FARMING THE WATERS

Most of us don’t think of the ocean when discussing agriculture. In fact, however, every year more and more of our animal protein is produced through aquaculture: the cultivation and harvesting of aquatic organisms under controlled conditions. Aquaculture includes mariculture, shrimp farming, oyster farming, fish farming, pearl cultivation, and more. In the heart of Brooklyn, New York, urban aquaculture thrives in a laboratory, where fish bound for New York City restaurants are harvested from indoor tanks. Aquaculture has its own distinctive cultural landscapes of containment ponds, rafts, nets, tanks, and buoys (Figure 8.15). Like terrestrial agriculture, there is a marked regional character to aquacultural production.

aquaculture

The cultivation, under controlled conditions, of aquatic organisms, primarily for food but also for scientific and aquarium uses.

mariculture

A branch of aquaculture specific to the cultivation of marine organisms, often involving the transformation of coastal environments and the production of distinctive new landscapes.

Aquaculture is an ancient practice, dating back at least 4500 years. Older local practices, sometimes referred to as traditional aquaculture, involve simple techniques such as constructing retention ponds to trap fish or “seeding” flooded rice fields with shrimp. Commercial aquaculture, the industrialized, large-scale protein factories driving today’s production growth, is a contemporary phenomenon. The greatest leaps in technology and production have occurred mostly since the 1970s.

At the turn of the twenty-first century, aquaculture was experiencing phenomenal growth worldwide, growing nearly four times faster than all terrestrial animal food-producing sectors combined. Aquaculture is a key reason that per-capita protein availability has more than kept pace with population growth in recent decades. For example, China’s population grew 63 percent from 1970 to 2010, while its per-capita protein supply derived from aquaculture went from 1 kilogram to over 36 kilograms. By 2011 aquaculture accounted for nearly two-thirds of all fish and seafood produced worldwide, compared with only 4 percent in 1970. Aquaculture’s share of production is projected to continue growing as demand for seafood increases and wild fish stocks decline.

329

The extraordinary expansion of food production by aquaculture has come with high costs to the environment and human health. As with industrialized agriculture, most commercial aquaculture relies on large energy and chemical inputs, including antibiotics and artificial feeds made from the wastes of poultry and hog processing. Such production practices tend to concentrate toxins in farmed fish, creating a potential health threat to consumers. The discharge from fish farms, which is equivalent to the sewage from a small city, can pollute nearby natural aquatic ecosystems. Around the tropics, especially tropical Asia, the expansion of commercial shrimp farms is contributing to the loss of highly biodiverse coastal mangrove forests.

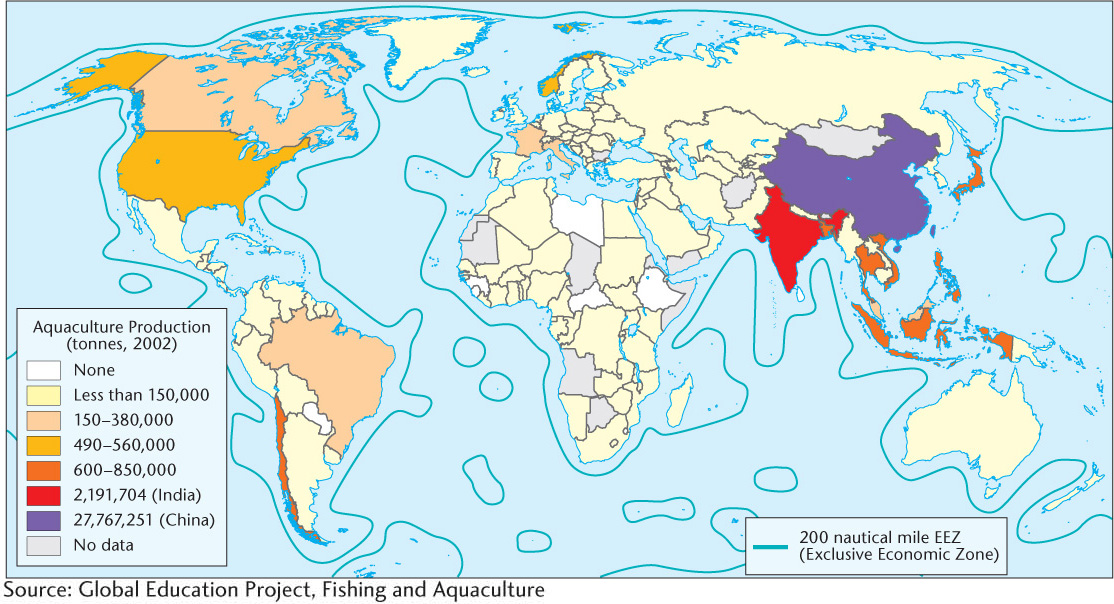

Although aquaculture can take place just about anywhere that water is found, strong regional patterns do exist. Mariculture is prevalent along tropical coasts, particularly in the mangrove forest zone. Marine coastal zones in general, especially in protected gulfs and estuaries, have high concentrations of mariculture. On a global scale, China dwarfs all other regions, producing over two-thirds of the world’s farmed seafood (Figure 8.16). Asia and the Pacific regions combined produce over 90 percent of the world’s total.

If you order shrimp, trout, or salmon for dinner at any of the myriad restaurant chains, you will almost certainly be eating farmed protein. As the populations of wild species decline and the price of captured fish increases, farmed seafood will increasingly move into the breach. If trends continue, we may be among the last generations to enjoy affordable fresh-caught wild fish.

NONAGRICULTURAL AREAS

Areas of extreme climate, particularly deserts and subarctic forests, do not support any form of agriculture. Such lands are found predominantly in much of Canada and Siberia. Often these areas are inhabited by hunting-and-gathering groups of native peoples, such as the Inuit, who gain a livelihood by hunting game, fishing where possible, and gathering edible and medicinal wild plants. Twelve thousand years ago, all humans lived as hunter-gatherers. Today, fewer than 1 percent of humans do. Given the various inroads of the modern world, even these people rarely depend entirely on hunting and gathering. In most hunting-and-gathering societies, a division of labor by gender occurs. Males perform most of the hunting and fishing, whereas females carry out the equally important task of gathering harvests from wild plants. Hunter-gatherers generally rely on a great variety of animals and plants for their food.

hunting and gathering

The killing of wild game and the harvesting of wild plants to provide food in traditional cultures.

330