MOBILITY

8.2

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Analyze the role mobility plays in the spatial and cultural patterns of agricultural production and food consumption.

Some of the variation among the agriculture regions we’ve discussed results from cultural diffusion. Agriculture and its many components are inventions; they arose as innovations in certain source areas and diffused to other parts of the worid. Mobility, as we shall see, is key in the expansion and functioning of the modern global food system.

cultural diffusion

The spread of elements of culture from the point of origin over an area.

ORIGINS AND DIFFUSION OF PLANT DOMESTICATION

Agriculture probably began with the domestication of plants. A domesticated plant is one that is deliberately planted, protected, cared for, and used by humans. Such plants are genetically distinct from their wild ancestors because they result from selective breeding by agriculturists. Accordingly, they tend to be bigger than wild species, bearing larger and more abundant fruit or grain. For example, the original wild “Indian maize” grew on a cob only one-tenth the size of the cobs of domesticated maize.

domesticated plant

A plant deliberately planted and tended by humans that is genetically distinct from its wild ancestors as a result of selective breeding.

331

Plant domestication and improvement constituted a process, not an event. It began as the gradual culmination of hundreds, or even thousands, of years of close association between humans and the natural vegetation. The first step in domestication was perceiving that a certain plant was useful, which led initially to its protection and eventually to deliberate planting.

Cultural geographer Carl Johannessen suggests that the domestication process can still be observed. He believes that by studying current techniques used by native subsistence farmers in places such as Central America, we can gain insight into the methods of the first farmers of prehistoric antiquity. Johannessen’s study of the present-day cultivation of the pejibaye palm tree in Costa Rica revealed that native cultivators actively engage in seed selection. All choose the seed of fresh fruit from superior trees, those that bear particularly desirable fruit, as determined by size, flavor, texture, and color. Superior seed stocks are built up gradually over the years, with the result that elderly farmers generally have the best selections. Seeds are shared freely within family and clan groups, allowing rapid diffusion of desirable traits.

The widespread association of female deities with agriculture suggests that it was women who first worked the land. Recall the almost universal division of labor in hunting-gathering-fishing societies. Because women had day-to-day contact with wild plants and their mobility was constrained by childbearing, they probably played the larger role in early plant domestication.

LOCATING CENTERS OF DOMESTICATION

When, where, and how did these processes of plant domestication develop? Most experts now believe that the process of domestication was independently invented at many different times and locations. Geographer Carl Sauer, who conducted pioneering research on the origins and dispersal of plant and animal domestication, was one of the first to propose this explanation.

Sauer believed that domestication did not develop in response to hunger. He maintained that necessity was not the mother of agricultural invention, because starving people must spend every waking hour searching for food and have no time to devote to the leisurely experimentation required to domesticate plants. Instead, he suggested this invention was accomplished by peoples who had enough food to remain settled in one place and devote considerable time to plant care. The first farmers were probably sedentary folk rather than migratory hunter-gatherers. He reasoned that domestication did not occur in grasslands or large river floodplains, because primitive cultures would have had difficulty coping with the thick sod and periodic floodwaters. Sauer also believed that the hearth areas of domestication must have been in regions of great biodiversity where many different kinds of wild plants grew, thus providing abundant vegetative raw material for experimentation and crossbreeding. Such areas typically occur in hilly districts, where climates change with differing sun exposure and elevation above sea level.

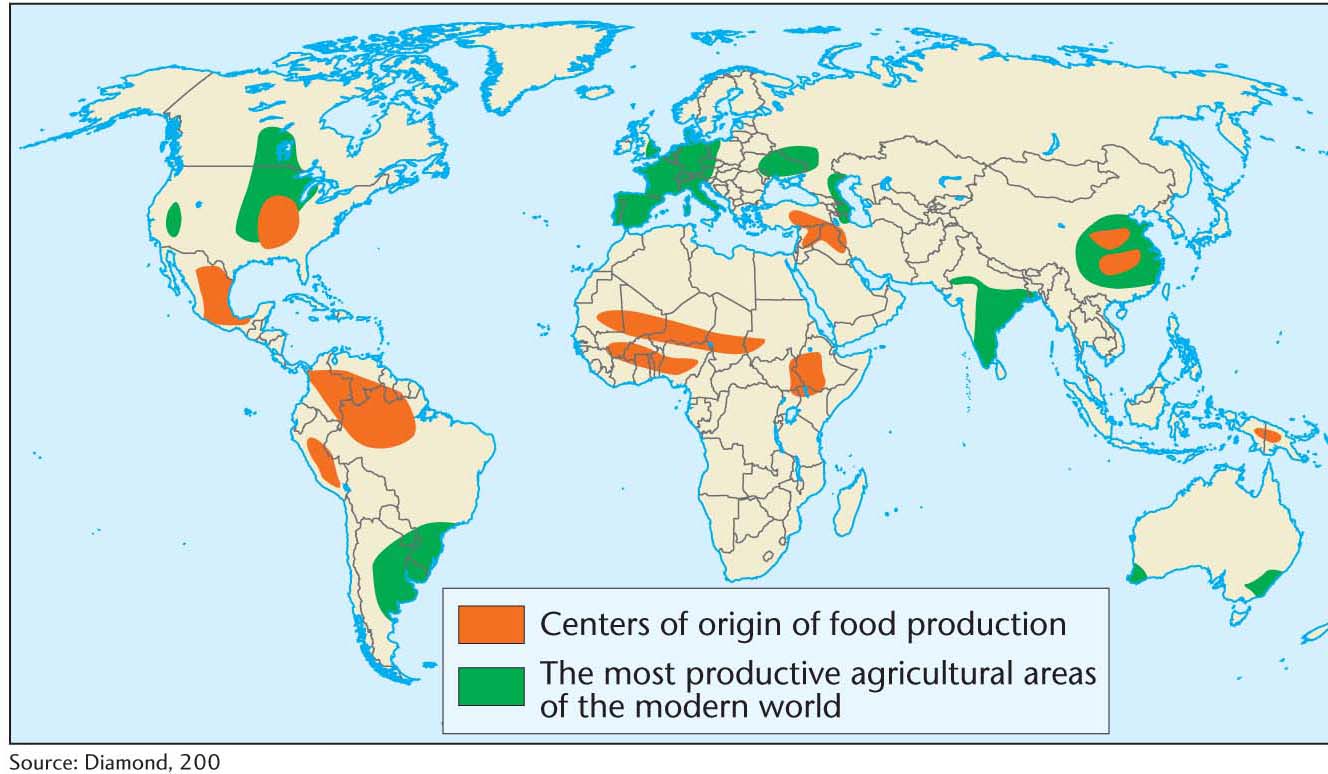

Geographers, archaeologists, and, increasingly, genetic scientists continue to investigate the geographic origins of domestication. Because the conditions conducive to domestication are relatively rare, most agree that agriculture arose independently in at most nine regions (Figure 8.17). All of these have made significant contributions to the modern global food system. For example, the Fertile Crescent in the Middle East is the origin of the great bread grains of wheat, barley, rye, and oats that are so key to our modern diets. This region is also home to the first domesticated grapes, apples, and olives. China and New Guinea provided rice, bananas, and sugarcane, while the African centers gave us peanuts, yams, and coffee. Native Americans in Mesoamerica created another important center of domestication, from which came crops such as maize (corn), tomatoes, and beans. Farmers in the Andes domesticated the potato. While crop diffusions out of these nine regions have occurred over the millennia, the forces of globalization have now made even the rarest of local domesticates available around the world.

332

The dates of earliest domestication are continually being updated by new research findings. Until recently, archaeological evidence suggested that the oldest center is the Fertile Crescent, where crops were first domesticated roughly 10,000 years ago. However, domestication dates for other regions are constantly being pushed back by new discoveries. Most dramatically, in the Peruvian Andes archaeologists recently excavated domesticated seeds of squash and other crops that they dated to 9240 years before the present. These seeds were associated with permanent dwellings, irrigation canals, and storage structures, suggesting that farming societies were established in the Americas 10,000 years ago, similar to the dating of the Fertile Crescent.

PETS OR MEAT? TRACING ANIMAL DOMESTICATION

A domesticated animal is one that depends on people for food and shelter and that differs from wild species in physical appearance and behavior as a result of controlled breeding and frequent contact with humans. Animal domestication apparently occurred later in prehistory than did the first planting of crops—with the probable exception of the dog, whose companionship with humans appears to be much more ancient. Typically, people value domesticated animals and take care of them for some utilitarian purpose. Certain domesticated animals, such as the pig and the dog, probably attached themselves voluntarily to human settlements to feast on garbage. At first, perhaps, humans merely tolerated these animals, later adopting them as pets or as sources of meat.

domesticated animal

An animal kept for some utilitarian purpose whose breeding is controlled by humans and whose survival is dependent on humans; domesticated animals differ genetically and behaviorally from wild animals.

The early farmers in the Fertile Crescent deserve credit for the first great animal domestications, most notably that of herd animals. The wild ancestors of major herd animals—such as cattle, pigs, horses, sheep, and goats—lived primarily in a belt running from Syria and southeastern Turkey eastward across Iraq and Iran to central Asia. Farmers in the Middle East were also the first to combine domesticated plants and animals in an integrated system, the antecedent of the peasant grain, root, and livestock farming described earlier. These people began using cattle to pull the plow, a revolutionary invention that greatly increased the acreage under cultivation. In other regions, such as southern Asia and the Americas, far fewer domestications took place, in part because suitable wild animals were less numerous. The llama, alpaca, guinea pig, Muscovy duck, and turkey were among the few American domesticates.

MODERN MOBILITIES

Over the past 500 years, European exploration and colonialism were instrumental in redistributing a wide variety of crops on a global scale: maize and potatoes from North America to Eurasia and Africa, wheat and grapes from the Fertile Crescent to the Americas, and West African rice to the Carolinas and Brazil.

333

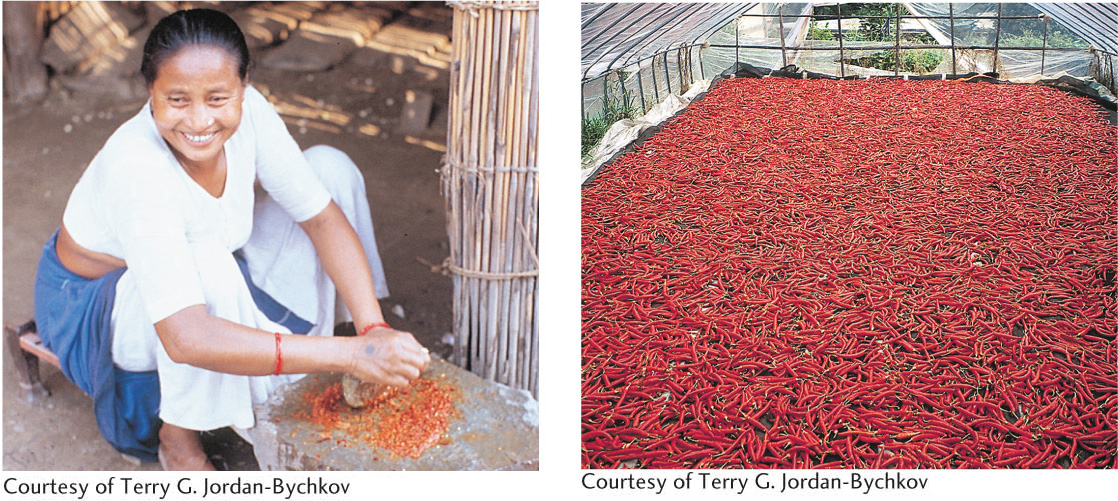

The diffusion of specific crops continues, extending the process begun many millennia ago. The introduction of the lemon, orange, grape, and date palm by Spanish missionaries in eighteenth-century California, where no agriculture existed in the Native American era, is a recent example of relocation diffusion. This was part of a larger process of multidirectional diffusion. Eastern Hemisphere crops were introduced to the Americas, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa through the mass emigrations from Europe over the past 500 years. Crops from the Americas diffused in the opposite direction. For example, chili peppers and maize, carried by the Portuguese to their colonies in South Asia, became staples of diets all across that region (Figure 8.18).

relocation diffusion

The spread of an innovation or other element of culture that occurs with the bodily relocation (migration) of the individual or group responsible for the innovation.

In cultural geography, our understanding of agricultural diffusion focuses on more than just the crops; it also includes an analysis of the cultures and indigenous technical knowledge systems in which they are embedded. For example, geographer Judith Carney’s study of the diffusion of African rice (Oryza glaberrima), which was domesticated independently in the inland delta area of West Africa’s Niger River, shows the importance of indigenous knowledge. European planters and slave owners carried more than seeds across the Atlantic from Africa to cultivate in the Americas. The Africans taken into slavery, particularly women from the Gambia River region, had the knowledge and skill to cultivate rice. Slave owners actively sought slaves from specific ethnic groups and geographic locations in the West African rice-producing zone, suggesting that they knew about and needed Africans’ skills and knowledge. Carney argues that the “association of agricultural skills with certain African ethnicities within a specific geographic region” means that research on agricultural diffusion must address the relation of culture to technology and the environment.

indigenous technical knowledge

Highly localized knowledge about environmental conditions and sustainable land-use practices.

334

Not all innovations involve expansion diffusion and spread wavelike across the land; less orderly patterns are more typical. The green revolution in Asia provides an example. The green revolution is a product of modern agricultural science that involves the development of high-yield hybrid varieties of crops, increasingly genetically engineered, coupled with extensive use of chemical fertilizers. The high-yield crops of the green revolution tend to be less resistant to insects and diseases, necessitating the widespread use of pesticides. The green revolution, then, promises larger harvests but ties the farmer to greatly increased expenditures for seed, fertilizer, and pesticides. It enmeshes the farmer in the global corporate economy. In some countries, most notably India, the green revolution diffused rapidly in the latter half of the twentieth century. By contrast, countries such as Myanmar resisted the revolution, favoring traditional methods. An uneven pattern of acceptance still characterizes the paddy rice areas today.

green revolution

The recent introduction of high-yield hybrid crops and chemical fertilizers and pesticides into traditional Asian agricultural systems, most notably paddy rice farming, with attendant increases in production and ecological damage.

The green revolution illustrates how cultural and economic factors influence patterns of diffusion. In India, for example, new hybrid rice and wheat seeds first appeared in 1966. These crops required chemical fertilizers and protection by pesticides, but with the new hybrids, India’s 1970 grain production output was double its 1950 level. However, poorer farmers— the great majority of India’s agriculturists—could not afford the capital expenditures for chemical fertilizer and pesticides, and the gap between rich and poor farmers widened. Many of the poor became displaced from the land and flocked to the overcrowded cities of India, aggravating urban problems. To make matters worse, the use of chemicals and poisons on the land heightened environmental damage.

The widespread adoption of hybrid seeds has created another problem: the loss of plant diversity or genetic variety. Before hybrid seeds diffused around the world, each farm developed its own distinctive seed types through the annual harvest-time practice of saving seeds from the better plants for the next season’s sowing. Enormous genetic diversity vanished almost instantly when farmers began purchasing hybrids rather than saving seed from the last harvest. “Gene banks” have belatedly been set up to preserve what remains of domesticated plant variety, not just in the areas affected by the green revolution but also in the American Corn Belt and many other agricultural regions where hybrids are now dominant. In sum, the green revolution has been a mixed blessing.

LABOR MOBILITY

Agriculture, more than any other modern economic endeavor, is constrained by the rhythms of nature. Biological cycles associated with planting and harvesting are reflected in cycles of labor demand. Seeds must be planted at the right moment to take advantage of seasonal conditions. When crops ripen, they must be harvested, often in a matter of days or weeks. In between, labor demand is minimal, so farmers face a dilemma. They need to mobilize a large labor force for harvesting crops, but keeping a year-round work force raises farm production costs. One solution has been to rely on migratory labor.

In the United States, the use of migrant workers has been central to the growth and profitability of farming. In his study of labor and landscape in California, geographer Don Mitchell found that the mechanization and intensification of farming created ever greater extremes in seasonal labor demand, lessening the demand for labor during nonharvest periods while still requiring manual labor for the increased harvests. Farmers thus developed an agricultural industry based on migratory labor, employing cultural and racial stereotypes to depress farm wages and tighten employers’ control over farmworkers. Mitchell noted that through much of the twentieth century, California growers surmised that “hispanic, black, or Asian workers . . . were ‘naturally’ better suited to agricultural tasks,” and prevailing racist attitudes allowed them to “pay nonwhite workers a lower wage than white workers.” Ultimately, the federal government provided the legal mechanism, called the Bracero Program, by which contract workers were brought from Mexico to California during periods of peak labor demand. Migrant workers lived in substandard housing, were paid less than a living wage, and were deported back to Mexico if they complained.

migrant workers

Most broadly, this term refers to people working outside of their home country. Migrant workers are particularly critical to large-scale commercial agriculture.

335

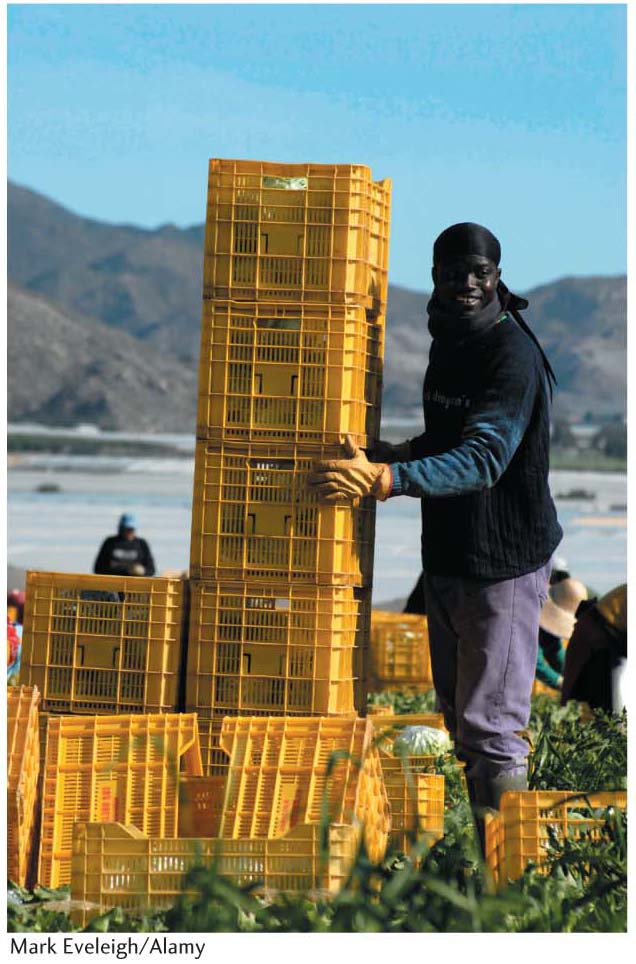

The case of California’s migrant workers is not unusual. Geographer Gail Hollander has documented the use of migratory labor in the development of Florida’s sugarcane region. Florida produces 20 percent of the U.S. sugar supply, which until the 1990s was harvested entirely by hand by migrant workers imported seasonally from “former slave plantation economies of the Caribbean.” Like their California counterparts, growers relied on racial stereotypes to argue that only blacks were suitable for cutting cane in Florida. The federal government also established a special federal immigration program like Bracero to import Caribbean migrant workers for the Florida harvest and repatriate them afterward. Migrant farmworkers remain ubiquitous today in other regions, too, such as the European Union. A recent agricultural boom in Mediterranean coastal Spain relies heavily on North African migrant workers, many of them undocumented immigrants, who are subject to persistent racial prejudices (Figure 8.19).