CONCLUSION

CONCLUSION

We have seen that the ancient human endeavor called agriculture varies markedly from region to region and is reflected in formal agricultural regions; we have also seen that we can better understand this complicated pattern through the themes of mobility, the global food system, nature-culture interactions, and agricultural landscape. Once again, we have seen the interwoven character of the five themes of cultural geography. In many fundamental ways, the agricultural revolution changed humankind. In equally dramatic fashion, the Industrial Revolution sparked further changes. We will use the five themes to guide an exploration of the industrial world in the next chapter.

361

DOING GEOGRAPHY

DOING GEOGRAPHY

The Global Geography of Food

Until recently, people throughout history obtained the food they needed either by growing it themselves or procuring it directly from nearby farmers. The choice and availability of food were limited and changed seasonally. About 100 years ago, this situation began to change dramatically as the pace of urbanization and industrialization accelerated. Today, very few people in developed countries grow their own food or even know where the food they eat was produced or who produced it. Where does our food come from? Who produces and sells it? Your task for this exercise is to find out.

This exercise can be organized as a group or individual project. As a group project, students can be assigned to research particular categories of food, such as meat and poultry, cereals and grains, fruits and vegetables, and dairy products. As an individual project, you should begin with a typical day’s meals and identify all their ingredients (don’t forget the seasonings and cooking oils used in preparing them).

Steps to Tracing the Global Geography of Food

Step 1:

The project starts at the food markets where you usually shop. For much of the information you will need, you can refer to the labels on the food items. For some items, such as fish, poultry, and meat, you may need to speak to the butcher or store manager. Find out, as specifically as possible, where the food item was produced. Find out the name of the company that marketed the product and, if available, the name of the parent company.

Step 2:

After collecting this basic information, you will need to log on to the Internet to do further research (the web sites listed in this chapter should be helpful). Organize a list of companies and the food products they market; then locate the geographic origins of each food product.

Step 3:

Now look for patterns.

■Which and how many companies are involved and what proportion of the food supply does each control?

■What proportion and which kinds of food are produced in other countries? Do certain kinds of foods tend to be produced closer to the market than others?

■Do certain kinds of food more so than others tend to be marketed by large corporations?

■Can you think of explanations for the patterns you identify?

You may wish to take this investigation to a greater depth.

■Can you determine from your research what conditions exist where the food is produced? For example, what landscape changes occur when regions begin producing for the global food system?

■How is production structured? Is it organized into large corporate plantations or small peasant farm plots?

■What are the ethical and social justice dimensions of food production?

■What are conditions like for workers?

■Have concerns over the treatment of animals been raised?

■Have environmental or human health concerns been raised?

362

SEEING GEOGRAPHY

SEEING GEOGRAPHY

Reading Agricultural Landscapes

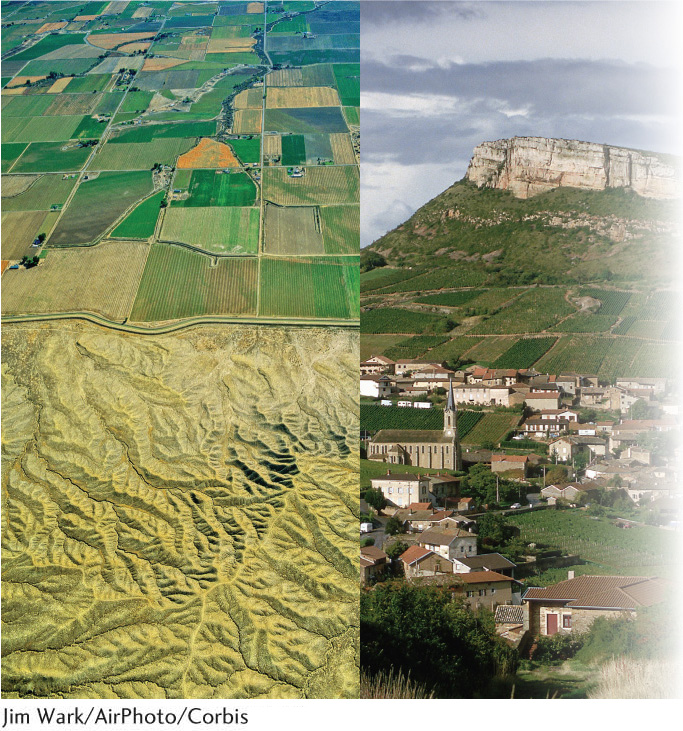

What differences can you “read” in these landscapes? Can you determine their locations?

Two types of contemporary agricultural landscapes.

(Left: Jim Wark/AirPhoto/Corbis; Right: Michael Busselle.)

Take a careful look at the two photos shown here and systematically identify the differences in each, beginning with the one on the left. The most striking aspect of this aerial landscape shot is the abrupt division between the cultivated land at the top and the noncultivated land at the bottom. Looking closely, we see that an irrigation channel forms the boundary between the two. A second prominent feature of the landscape is the checkerboard pattern of the fields and the straight roads forming their boundaries. Other details emerge as you look more closely. For example, the settlement pattern consists of isolated, sparsely arranged farmsteads separated by large expanses of cultivated fields. You might also note that the uncultivated land is brown and treeless and that trees in the cultivated portion are found only along the watercourses.

The landscape features in the photo on the right are nearly the opposite of those in the image on the left. Settlement is clustered in a densely populated village centered on a church and town square. The fields are of irregular sizes and shapes and form a band of cultivated land around the concentrations of houses, some of which are built of stone. There is no clear evidence of irrigation. Trees and shrubs are concentrated in the outermost band but also occur throughout the landscape, which overall appears verdant.

Putting all these visual clues together leads us to conclude that the landscape on the left must be somewhere in the western United States. We know this region was surveyed and settled under the township and range system, which explains the isolated farmsteads and checkerboard pattern. We also know that much of the western United States is arid or semiarid, which explains the need for irrigation and the general lack of trees and green vegetation in the bottom half of the photo. In fact, this is a photo of Mack, Colorado, where irrigation meets the desert. The landscape on the right is probably located in Europe. The large church in the center and dense cluster of houses suggest the settlement pattern of a historical market town. The irregular fields and their close proximity to the town are explained by deep historical patterns of land ownership and the reliance on foot travel in preindustrial agriculture. The verdant landscape and absence of irrigation suggest the temperate climate characteristic of western Europe. In fact, you are looking at the vineyard region of Saöne-et-Loire, France.

363

Chapter 8 LEARNING OBJECTIVES REEXAMINED

Chapter 8

LEARNING OBJECTIVES REEXAMINED

8.1

Explain the connection between region and agriculture.

How is the theme of region relevant to agriculture?

8.2

Analyze the role mobility plays in the spatial and cultural patterns of agricultural production and food consumption.

What role does cultural diffusion play in the variation of agriculture regions?

8.3

Describe how the processes of globalization alter the geography of agriculture.

How does globalization affect the availability and variety of food in specific places?

8.4

Understand how nature-culture relations are expressed through the production and consumption of food.

What role does sustainability play in nature-culture relations?

8.5

Relate how agriculture is expressed within the cultural landscape.

What is meant by the agricultural landscape and what does it tell us about cultures?

KEY TERMS

Match each of the terms on the left with its definition on the right. Click on the term first and then click on the matching definition. As you match them correctly they will move to the bottom of the activity.

Question

agribusiness agricultural landscape agricultural region agriculture aquaculture biofuel cadastral pattern conventional agriculture cool chain core-periphery cultural diffusion culturally preadapted desertification domesticated animal domesticated plant double-cropping extensive agriculture feedlot folk culture foodborne disease outbreaks genetically modified (GM) crops globalization green revolution hamlet hunting and gathering indigenous technical knowledge intensive agriculture intercropping livestock fattening mariculture market gardening migrant workers monoculture nomadic livestock herder organic agriculture paddy rice farming peasant plantation plantation agriculture ranching relocation diffusion sedentary cultivation subsistence agriculture suitcase farm survey pattern sustainability swidden cultivation urban agriculture | The commercial raising of herd livestock on a large landholding. The recent introduction of high-yield hybrid crops and chemical fertilizers and pesticides into traditional Asian agricultural systems, most notably paddy rice farming, with attendant increases in production and ecological damage. The raising of only one crop on a huge tract of land in agribusiness. A farmer belonging to a folk culture and practicing a traditional system of agriculture. A process whereby human actions unintentionally turn productive lands into deserts through agricultural and pastoral misuse, destroying vegetation and soil to the point where they cannot regenerate. The survival of a land-use system for centuries or millennia without destruction of the environmental base, allowing generation after generation to continue to live there. The cultivation, under controlled conditions, of aquatic organisms, primarily for food but also for scientific and aquarium uses. Plants whose genetic characteristics have been altered through recombinant DNA technology. The cultural landscape of agricultural areas. Broadly, this term refers to any form of energy derived from biological matter, increasingly used in reference to replacements for fossil fuels in internal combustion engines, industrial processes, and the heating and cooling of buildings. A system of monoculture for producing export crops requiring relatively large amounts of land and capital; originally dependent on slave labor. Farming devoted to specialized fruit, vegetable, or vine crops for sale rather than consumption. A factorylike farm devoted to either livestock fattening or dairying; all feed is imported and no crops are grown on the farm. The widely adopted commercial, industrialized form of farming that uses a range of synthetic fertilizers, insecticides, and herbicides to control pests and maximize productivity; a term that emerged following the creation of alternative forms, such as organic farming. The cultivation of rice on a paddy, or small flooded field enclosed by mud dikes, practiced in the humid areas of the Far East. The practice of growing two or more different types of crops in the same field at the same time. (See cultural preadaptation) The cultivation of domesticated crops and the raising of domesticated animals. Highly localized knowledge about environmental conditions and sustainable land-use practices. The killing of wild game and the harvesting of wild plants to provide food in traditional cultures. A type of agriculture characterized by land rotation in which temporary clearings are used for several years and then abandoned to be replaced by new clearings; also known as slash-and-burn agriculture. A form of farming that relies on manuring, mulching, and biological pest control and rejects the use of synthetic fertilizers, insecticides, herbicides, and genetically modified crops. When two or more people acquire the same illness from the same contaminated food or drink. A small rural settlement, smaller than a village. Highly mechanized, large-scale farming, usually under corporate ownership. An animal kept for some utilitarian purpose whose breeding is controlled by humans and whose survival is dependent on humans; domesticated animals differ genetically and behaviorally from wild animals. A plant deliberately planted and tended by humans that is genetically distinct from its wild ancestors as a result of selective breeding. The raising of food, including fruit, vegetables, meat, and milk, inside cities, especially common in the Third World. A branch of aquaculture specific to the cultivation of marine organisms, often involving the transformation of coastal environments and the production of distinctive new landscapes. The binding together of all the lands and peoples of the world into an integrated system driven by capitalistic free markets, in which cultural diffusion is rapid, independent states are weakened, and cultural homogenization is encouraged. A large landholding devoted to specialized production of a tropical cash crop. Harvesting twice a year from the same parcel of land. Most broadly, this term refers to people working outside of their home country. Migrant workers are particularly critical to large-scale commercial agriculture. The refrigeration and transport technologies that allow for the distribution of perishables. A concept based on the tendency of both formal and functional culture regions to consist of a core or node, in which defining traits are purest or functions are headquartered, and a periphery that is tributary and displays fewer of the defining traits. Farming in fixed and permanent fields. A geographic region defined by a distinctive combination of physical and environmental conditions; crop type; settlement patterns; and labor, cultivation, and harvesting practices. A pattern of original land survey in an area. A small, cohesive, stable, isolated, nearly self-sufficient group that is homogeneous in custom and race; characterized by a strong family or clan structure, order maintained through sanctions based in the religion or family, little division of labor other than that between the sexes, frequent and strong interpersonal relationships, and a material culture consisting mainly of handmade goods. The expenditure of much labor and capital on a piece of land to increase its productivity. In contrast, extensive agriculture involves less labor and capital. The spread of an innovation or other element of culture that occurs with the bodily relocation (migration) of the individual or group responsible for the innovation. A member of a group that continually moves with its livestock in search of forage for its animals. The practices of farming and livestock raising using low levels of labor and capital relative to the areal extent of land under production, relying chiefly on natural soil fertility and prevailing climate. Farming to supply the minimum food and materials necessary to survive. The spread of elements of culture from the point of origin over an area. The shapes formed by property borders; the pattern of land ownership. A commercial type of agriculture that produces fattened cattle and hogs for meat. In American commercial grain agriculture, a farm on which no one lives; planting and harvesting are done by hired migratory crews. |

Agricultural Geography on the Internet

You can learn more about agricultural geography on the Internet at the following web sites:

Agriculture, Food, and Human Values (AFHVS)

Founded in 1987, AFHVS promotes interdisciplinary research and scholarship in the broad areas of agriculture and rural studies. The organization sponsors an annual meeting and publishes a journal by the same name.

Food First

Founded in 1975 by author-activist Francis Moore Lappé, Food First is a nonprofit, “people’s” think tank and clearinghouse for information and political action. The organization highlights root causes and value-based solutions to hunger and poverty around the world, with a commitment to establishing food as a fundamental human right.

International Food Policy Research Institute

Learn about strategies for more efficient planning for world food supplies and enhanced food production from a group concerned with hunger and malnutrition. Part of this site deals with domesticated plant biodiversity.

Resources for the Future

This well-respected center for independent social science research was the first U.S. think tank on the environment and natural resources. This site contains a great deal of information related to the environmental aspects of global food and agriculture.

United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)

Discover an agency that focuses on expanding world food production and spreading new techniques for improving agriculture as it strives to predict, avert, or minimize famines.

United States Department of Agriculture

Look up a wealth of statistics about American farming from the principal federal regulatory and planning agency dealing with agriculture.

364

Urban Agriculture Notes

This is the site of Canada’s Office of Urban Agriculture. It concerns itself with all manner of subjects, from rooftop gardens to composting toilets to air pollution and community development. It encompasses mental and physical health, entertainment, building codes, rats, fruit trees, herbs, recipes, and much more.

World Bank Group

Read about an agency that provides development funds to countries, particularly in economically distressed regions. It is a driving force behind globalization and agribusiness.

Worldwatch Institute

Learn about a privately financed organization focused on long-range trends, particularly food supply, population growth, and ecological deterioration.

Your Food Environment Atlas

A powerful, interactive mapping site that currently includes 90 indicators of the food environment ranging from store/restaurant proximity to income and poverty measures.

Sources

Andrews, Jean. 1993. “Diffusion of Mesoamerican Food Complex to Southeastern Europe.” Geographical Review 83: 194-204.

Bassett, Thomas, and Alex Winter-Nelson. 2010. The Atlas of World Hunger. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bourne, Joel, Jr. 2007. “Biofuels: Boon or Boondoggle.” National Geographic Magazine 212(4): 38-59.

Boyd, William, and Michael Watts. 1997. “Agroindustrial Just-In-Time: The Chicken Industry and Postwar American Capitalism.” In M. Watts and D. Goodman (eds.), Globalizing Food: Agrarian Questions and Global Restructuring, pp. 192-225. London: Routledge.

Carney, Judith. 2001. Black Rice: The African Origins of Rice Cultivation in the Americas. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Carter, Eric, Bianca Silva, and Graciela Guzman. 2013. “Migration, Acculturation, and Environmental Values: The Case of Mexican Immigrants in Central Iowa.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 130(1): 129-147.

Centers for Disease Control. Tracking and Reporting Foodborne Disease Outbreaks. http://www.cdc.gov/Features/dsFoodborneOutbreaks/.

Chakravarti, A. K. 1973. “Green Revolution in India.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 63: 319-330.

Cowan, C. Wesley, and Patty J. Watson (eds.). 1992. The Origins of Agriculture: An International Perspective. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Cross, John A. 1994. “Agroclimatic Hazards and Fishing in Wisconsin.” Geographical Review 84: 277-289.

Darby, H. Clifford. 1956. “The Clearing of the Woodland in Europe.” In William L. Thomas, Jr. (ed.), Man’s Role in Changing the Face of the Earth, pp. 183-216. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Demangeon, Albert. 1946. La France. Paris: Armand Colin.

Diamond, Jared. 2002. “Evolution, Consequences and Future of Plant and Animal Domestication.” Nature 418: 700-707.

Dillehay, T., J. Rossen, T. Andres, and D. Williams. 2007. “Preceramic Adoption of Peanut, Squash, and Cotton in Northern Peru.” Science 316(5833): 1890-1893.

Global Education Project. 2014. Earth: A Graphic Look at the State of the World. “Fisheries and Agriculture.” http://www.theglobaleducationproject.org/earth/fisheries-and-aquaculture.php.

Ewald, Ursula. 1977. “The von Thünen Principle and Agricultural Zonation in Colonial Mexico.” Journal of Historical Geography 3: 123-133.

Freidberg, Susanne. 2001. “Gardening on the Edge: The Conditions of Un-sustainability on an African Urban Periphery.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 91(2): 349-369.

Griffin, Ernst. 1973. “Testing the von Thünen Theory in Uruguay.” Geographical Review 63: 500-516.

Griliches, Zvi. 1960. “Hybrid Corn and the Economics of Innovation.” Science 132 (26 July): 275-280.

Guthman, Julie. 2004. Agrarian Dreams: The Paradox of Organic Farming in California. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Harris, Gardiner. 2013. “Farmers Change over Spices’ Link to Food Ills.” New York Times, 27 August, A1.

Hewes, Lewlie. 1973. The Suitcase Farming Frontier: A Study in the Historical Geography of the Central Great Plains. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Heynen, Nik. 2010. “Cooking Up Non-Violent Civil Disobedient Direct Action for the Hungry: Food Not Bombs and the Resurgence of Radical Democracy.” Urban Studies 47(6): 1225-1240.

Hidore, John J. 1963. “Relationship Between Cash Grain Farming and Landforms.” Economic Geography 39: 84-89.

Hollander, Gail. 2008. Raising Cane in the ‘Glades: The Global Sugar Trade and the Transformation of Florida. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Horvath, Ronald J. 1969. “Von Thünen’s Isolated State and the Area Around Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 59: 308-323.

ISAAA. 2007. International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-biotech Applications web site. http://www.isaaa.org.

Johannessen, Carl L. 1966. “The Domestication Processes in Trees Reproduced by Seed: The Pejibaye Palm in Costa Rica.” Geographical Review 56: 363-376.

Mathews, Kenneth, Jason Bernstein, and Jean Buzby. 2003. “International Trade of Meat and Poultry Products and Food Safety Issues.” In Jean Buzby (ed.), International Trade and Food Safety: Economic Theory and Case Studies. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service.

Millstone, Erik, and Tim Lang. 2003. The Penguin Atlas of Food. New York: Penguin.

Mitchell, Don. 1996. The Lie of the Land: Migrant Workers and the California Landscape. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Murphey, Rhoads. 1951. “The Decline of North Africa Since the Roman Occupation: Climatic or Human?” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 41: 116-131.

Norberg-Hodge, Helena, Todd Merrifield, and Steven Gorelick. 2002. Bringing the Food Economy Home: Local Alternatives to Global Agribusiness. London: Zed.

Popper, Deborah E., and Frank Popper. 1987. “The Great Plains: From Dust to Dust.” Planning 53(12): 12-18.

Saarinen, Thomas F. 1966. Perception of Drought Hazard on the Great Plains. University of Chicago, Department of Geography, Research Paper No. 106. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

365

Sauer, Carl O. 1952. Agricultural Origins and Dispersals. New York: American Geographical Society.

Sauer, Jonathan D. 1993. Historical Geography of Crop Plants. Boca Raton, Fla.: CRC Press.

Schlenker, Wolfram, and David B. Lobell. 2010. “Robust Negative Impacts of Climate Change on African Agriculture.” Environmental Research Letters 5(1): 1-8.

Strom, Stephanie. 2013. “Food Supplier Grapples with Frequent Recalls.” New York Times, 29 August, B1.

Thrower, Norman J. W. 1966. Original Survey and Land Subdivision. Chicago: Rand McNally.

United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization. 2013. Food Outlook. Rome: UNFAO.

U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2004. Economic Research Service web site. http://www.ers.usda.gov.

Vogeler, Ingolf. 1981. The Myth of the Family Farm: Agribusiness Dominance of United States Agriculture. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press.

von Thünen, Johann Heinrich. 1966. Von Thünen’s Isolated State: An English Edition of Der Isolierte Staat. Carla M. Wartenberg (trans.). Elmsford, N.Y.: Pergamon.

Wallander, Steven, Roger Claassen, and Cynthia Nickerson. 2011. The Ethanol Decade: An Expansion of U.S. Corn Production, 2000-09. Economic Information Bulletin Number 79. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service.

Westcott, Paul. 2007. Ethanol Expansion in the United States: How Will the Agricultural Sector Adjust? Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service.

Wilken, Gene C. 1987. Good Farmers: Traditional Agricultural and Resource Management in Mexico and Central America. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Zimmerer, Karl. 1996. Changing Fortunes: Biodiversity and Peasant Livelihood in the Peruvian Andes. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Ten Recommended Books on Agricultural Geography

(For additional suggested readings, see the Contemporary Human Geography LaunchPad: macmillanhighered.com/launchpad/DomoshCHG1e.)

Bassett, Thomas, and Alex Winter-Nelson. 2010. The Atlas of World Hunger. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. The authors map out the geography and causes of world hunger from a critical social science perspective.

Clay, Jason. 2004. World Agriculture and the Environment: A Commodity-by-Commodity Guide to Impacts and Practices. Washington, D.C., and Covelo, Calif.: Island Press. This book describes the environmental effects resulting from the production of 22 major crops; it is global in scope and encyclopedic in detail.

Denham, Tim, Jose Iriarte, and Luc Vrydaghs (eds.). 2007. Rethinking Agriculture: Archeological and Ethnoarcheological Perspectives. Walnut Creek, Calif.: Left Coast Press. An edited volume bringing together geographers, anthropologists, and archaeologists to present the latest research findings on the origins of early agriculture in non-Eurasian regions.

Freidberg, Susanne. 2010. Fresh: A Perishable History. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. A wonderfully written cultural and historical geography study of the pursuit of freshness in the global food system. The range of topics is sweeping and includes every link in the commodity chain from farm to table.

Gertel, Jorg, and Richard Le Heron (eds.). 2011. Economic Spaces of Pastoral Production and Commodity Systems. Williston, Vt.: Ashgate Press. A deeply ethnographic collection of studies on pastoralism in the twenty-first century. It provides an enlightening set of comparative cases from around the world, including countries typically underrep-resented in such collections.

Millstone, Erik, and Tim Lang. 2008. The Atlas of Food: Who Eats What, Where, and Why. 2nd ed. Berkeley: University of California Press. A book packed with information on global agriculture on a wide range of topics, including genetically modified crops, fast food, organic farming, and more, all presented in brilliantly detailed maps.

Morgan, Kevin, Terry Marsden, and Jonathan Murdoch. 2006. Worlds of Food: Place, Power and Provenance in the Food Chain. Oxford: Oxford University Press. A valuable contribution to twenty-first-century studies of the global food system. Its authors link recent cultural shifts in food preference to the emergence of an alternative geography of agriculture that emphasizes the importance of place and region.

Sauer, Carl O. 1969. Seeds, Spades, Hearths, and Herds. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. The renowned American cultural geographer presents his theories on the origins of plant and animal domestication—the beginnings of agriculture.

Watts, M., and D. Goodman (eds.). 1997. Globalizing Food: Agrarian Questions and Global Restructuring. London: Routledge. This edited volume, containing primarily the work of geographers, analyzes globalization and the biotechnological revolution in agriculture.

Woods, Michael. Rural. 2011. New York: Routledge. Part of the “Key Ideas in Geography” series from the publisher. This is wide-ranging synopsis of the latest geographic research on the rural, including but not limited to issues of food and agriculture. It is particularly strong in addressing the themes of globalization and landscape in contemporary rural spaces.

Journals in Agricultural Geography

Agriculture and Human Values. An interdisciplinary journal dedicated to the study of ethical questions surrounding agricultural practices and food. Published by Kluwer. Volume 1 appeared in 1984. Visit the homepage of the journal at http://link.springer.com/journal/10460.

Journal of Agrarian Change. A journal focusing on agrarian political economy, featuring both historical and contemporary studies of the dynamics of production, property, and power. Published by John Wiley & Sons. Volume 1 appeared in 2000. Visit the homepage of the journal at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/10.1111/(ISSN)1471-0366.

Journal of Peasant Studies. One of the leading journals of rural development, especially focused on marginalized agricultural communities and social groups in Third World regions. Published by Taylor & Francis. Volume 1 appeared in 1973. Visit the homepage of the journal at http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fjps20#.UokN85hZ6ew.

Journal of Rural Studies. An international interdisciplinary journal ranked as the best of its kind. Published by Pergamon, an imprint of Elsevier Science, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Volume 1 appeared in 1985. Visit the homepage of the journal at http://www.journals.elsevier.com/journal-of-rural-studies/.