REGION

9.1

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Discuss the history of development and how it has shaped, and reshaped, regions.

You may have had the experience of traveling to countries or regions where the everyday conditions of life seem so much more difficult than the conditions you are accustomed to at home. If you haven’t traveled to such places, you certainly have seen enough television shows, movies, and Internet content to understand that the everyday lives of people in different parts of the world, including their access to housing, food, and health care, may differ greatly from yours. You may also notice differences within your own neighborhood, town, or city, in the quality of life of the people who live around you.

We’ve already touched on many development-related topics throughout the book, which tells you that development is a concept that reaches into many areas of human geography. In the chapter introduction that you just read, we also noted that development includes but exceeds mere wealth as defined in economic terms. It is important to understand exactly what is meant by development and how this idea has evolved, because the term is a powerful one that has literally shaped and reshaped the world in which we live.

373

374

DEVELOPMENT: A BRIEF HISTORY

The term development emerged in the post-World War II era when scholars as well as government and policy officials, particularly those in the United States, became concerned that the standard of living in many regions of the world was quite low. By standard of living, they were referring to such things as literacy rates, infant mortality, life expectancy, and poverty levels. They realized that, in general, a low standard of living was most prevalent in countries whose economies were based primarily on subsistence agriculture (see Chapter 8). These officials and scholars believed that introducing new technologies and skills would enable these countries to develop more productive forms of agriculture, and that industrialization—the transformation of raw materials into commodities—would follow. These new economic initiatives would then lead to a higher standard of living. Transforming the economic structure of a region in order to raise the standard of living is what at that time was known as development. The term development referred to a process of both economic and social transformation, and provided a way of categorizing different regions of the world.

One of the earliest and most influential models of the process of economic development was suggested by the economist W. W. Rostow in 1962. Rostow posited that economic development was a process that all regions of the world would go through and experience in similar ways. His model assumed that regions would progress in a linear fashion through defined economic stages as they developed, much like an airplane pulling out of the gate, taxiing along the runway, taking off, and ultimately flying high. The first stage, which he called a “traditional” economy, is one that is based on agriculture and has limited access to or knowledge of advanced technologies: in other words, the economy is undeveloped. This first stage would be followed by a series of other stages characterized by increasing technological sophistication and the introduction of industrialization. Rostow’s final stage, called the “age of high mass consumption,” is the stage that he saw as characteristic of economies in the United States and much of western Europe. In this final stage of development, industrialization has gained such momentum that goods and services are widely available and most people can accumulate wealth to such a degree that they no longer have to worry about meeting basic needs. According to Rostow, the reason some countries were developed while others were not was that they were simply at different stages along the same flight path. Eventually, however, all nations would reach the “cruising altitude” of development as defined by high levels of mass consumption.

Rostow’s model has been criticized by scholars for a variety of reasons. While the simplicity of the model is appealing, its assumptions about the world often don’t match up to reality. For example, the model suggests that countries and regions proceed along the path to development in isolation from one another. But as we will see in this chapter, different countries and their economies are interlinked in complex ways; for example, if one country’s economy is based primarily on producing goods and services, it needs other regions and economies to supply its food and raw materials. In addition, the model assumes that all economies will develop without obstacles from other countries, and we know that this is rarely true, since, for example, some countries may deliberately try to block economic development in other countries that they think will become their competitors. Indeed, some critics of Rostow’s approach claimed that developed countries—those enjoying high levels of mass consumption—depended on the exploitation and impoverishment of other regions in order to achieve their success. The cheap natural and human resources of less developed regions were exploited in order to permit more developed regions to enrich themselves. In other words, underdevelopment of some places is an active process that goes hand-in-hand with the development of others. Finally, the end goal of Rostow’s development model—consuming lots of material goods—may not be considered as desirable as other goals, such as political freedom or decent working conditions.

375

In this chapter, we use the terms developing and developed to refer to different regions of the world, but we don’t assume, like the Rostow model does, that there is a normal and linear progression from one stage of development to another. We use the term developing to refer to regions whose economies include not only a good deal of subsistence activities but also some manufacturing and service activities. In these regions, people are often unable to accumulate wealth, since they produce just enough, or at times not enough, food and other resources for their own immediate needs. These countries therefore have a lower GDP and are considered relatively poor. We use the term developed to refer to those regions of the world whose economies are based more on manufacturing, services, and information. These regions have a higher GDP and are considered wealthier because people living there are better able to accumulate resources. The landscape of development is a complex one, as individual cities, regions, and countries can contain a mixture of developed as well as underdeveloped places.

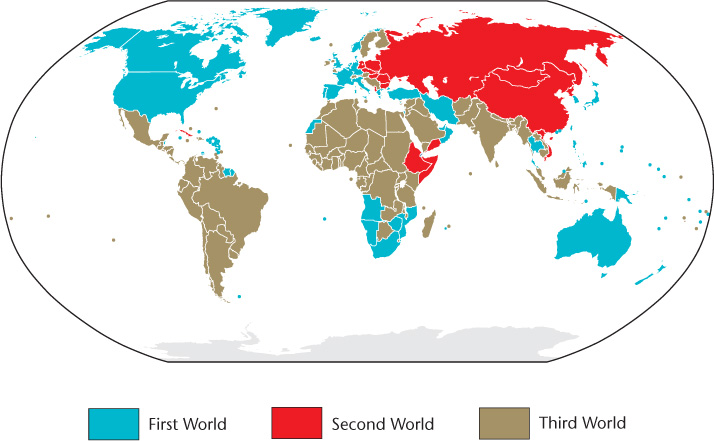

There have been other ways of using notions of development to categorize the world into regions. For instance, during the mid-twentieth century, the world was seen as being divided into the First, Second, and Third Worlds (Figure 9.9). The First World represented the world’s wealthy, democratic, capitalist nations, while the Third World was made up of poor countries. Because the so-called Cold War was the principal frame for power from the end of World War II in 1945 to the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, these labels also had political meanings. The Second World consisted of those countries that were ruled by communist or socialist governments and had central or command economies, rather than capitalist ones. The Third World nations were not aligned with either the First or Second World. After 1991 the terms First, Second, and Third World had primarily economic connotations, along with the Fourth World, those regions considered to be so poor that they existed beyond the reach of contemporary society.

First World

A term used to describe the group of wealthy, democratic, capitalist nations across the world.

Third World

A term used to describe the world’s poor nations as a group. During the Cold War era, these were also the nations that were not communist or socialist; in other words, they were not aligned with either the First or Second World.

Second World

A term used during the Cold War era to describe the group of countries that were communist or socialist in their governmental philosophy, and had centrally planned rather than free-market economic systems.

Fourth World

A term used to describe the world’s poorest nations.

376

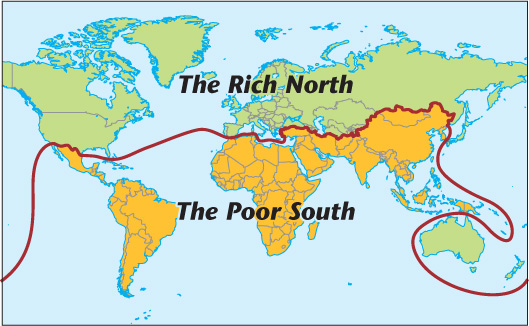

In the 1970s, West German Chancellor Willy Brandt proposed what came to be known as the Brandt Line as a way of understanding the world. The Brandt Line divided the countries of the world into two regions: wealthy and poor (Figure 9.10). Notice that wealthy countries tend to be in the Northern Hemisphere, while poorer ones are in the Southern Hemisphere.

Brandt Line

Division of the countries of the world into two regions: wealthy and poor. The Brandt Line is nam ed after former West German Chancellor Willy Brandt, and was a concept commonly applied in the 1970s through the 1980s.

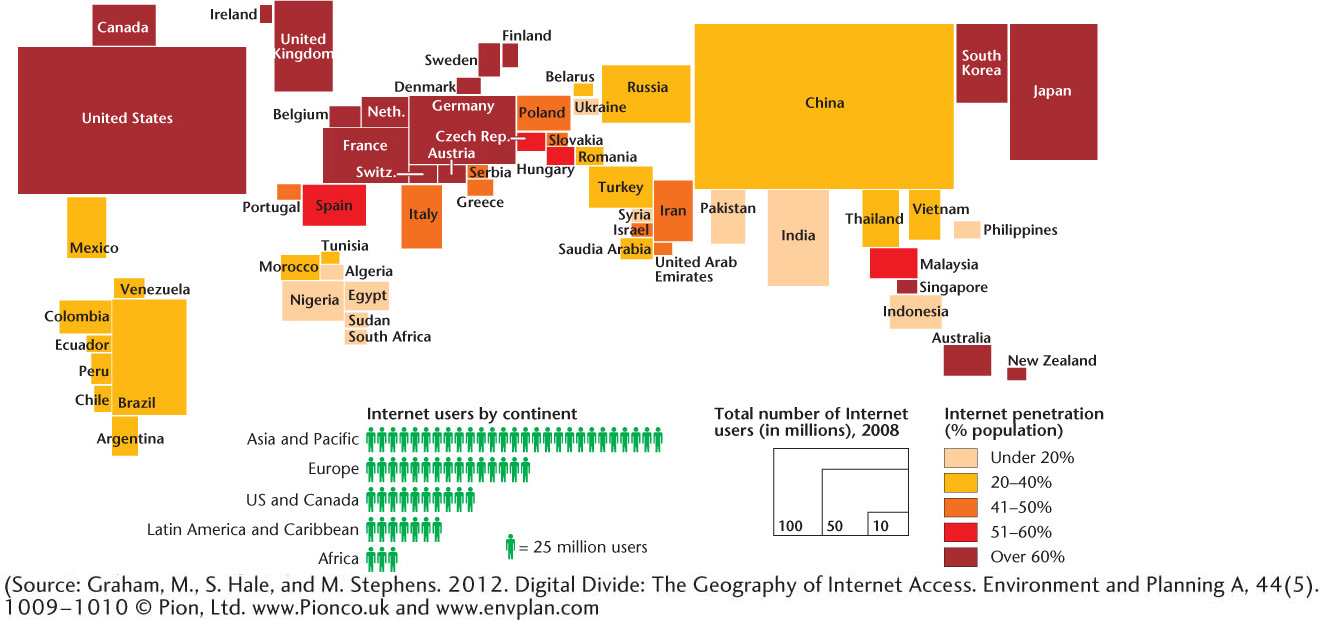

By the 1980s, however, many places in the so-called Third World had made significant economic advances, and the Cold War had lost some of its traction as an organizing framework with which to understand power in the world. Thus, the division of the globe into different regions, by the political and economic criteria represented by the four worlds, or the “have” versus “have-not” distinction demarcated by the Brandt Line, fell out of fashion. Today, you can find divisions of the globe that focus on its more contemporary development aspects—for instance, highlighting the world’s fast-emerging economies, or those with access to resources such as technology, which distinguish the current haves from have-nots (Figure 9.11).

CATEGORIZING TYPES OF ECONOMIC ACTIVITY BY SECTOR

In order to fully understand the differences and similarities between regions, it is helpful to distinguish the types of economic activities that characterize them. In general, scholars divide types of economic activities into four broad categories, or sectors. Primary sector activities involve extracting natural resources from the Earth. Fishing, farming, hunting, lumbering, oil extraction, and mining are examples of primary industries. Secondary sector activities process the raw materials extracted by primary industries, transforming them into more usable forms. Ore is converted into steel; logs are milled into lumber; and fish are processed and canned. Manufacturing is a more common way of referring to secondary industries. Manufacturing activities are found throughout the world, but, as we will discuss later in this chapter, they tend to cluster in particular areas because of favorable circumstances such as cheap power sources or available labor.

primary sector

The set of economic activities that involves extracting natural resources from the Earth.

secondary sector

The set of economic activities that involves processing the raw materials extracted by primary sector activities into usable goods. Commonly referred to as manufacturing.

In parts of the world where people import the bulk of their manufactured products, economic activities are dominated by services. Services comprise the tertiary sector, which refers to all the different types of work necessary to move goods and resources around and deliver them to people. So wide is the range of services that some geographers find it useful to distinguish three different types: transportation/communication services, producer services, and consumer services. Finally, the fastest-emerging set of economic activity is occurring in the quaternary sector. The quaternary sector includes intellectual and informational activities.

tertiary sector

The set of economic activities that refers to all the different types of work necessary to move goods and resources around and deliver them to people; in other words, service activities.

quaternary sector

Intellectual and informational economic activities.

377

DEVELOPMENT ACTORS

Now that you have some idea of the various definitions and approach es to development, it is logical to ask who “does” development and what kinds of activities count as development?

Traditionally, there have been several major actors in the field of development. International bodies specifically charged with some aspect of economic development, many of them emerging from the aftermath of World War Two, include the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and the United Nations Development Programme. Others are more focused on basic needs fulfillment, such as the World Health Organization that targets disease eradication or Oxfam that provides hunger relief. Such bodies have played longstanding and visible roles in international development by setting agendas for development, providing expertise, and coordinating policies and people. Some churches and religiously affiliated nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) also provide development assistance in cash or in kind. Sometimes their assistance is offered internationally, but it can be locally targeted at specific neighborhoods.

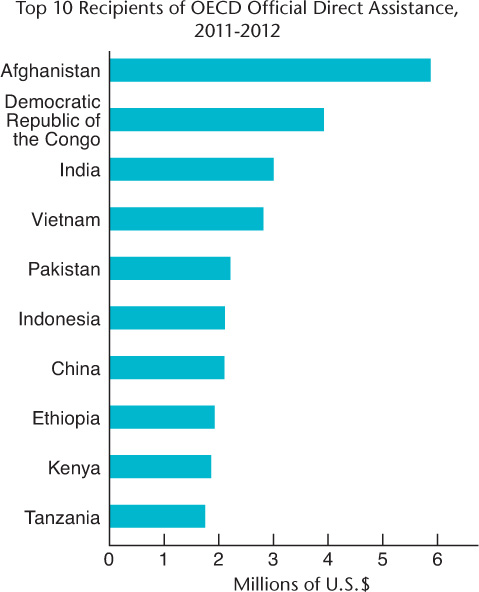

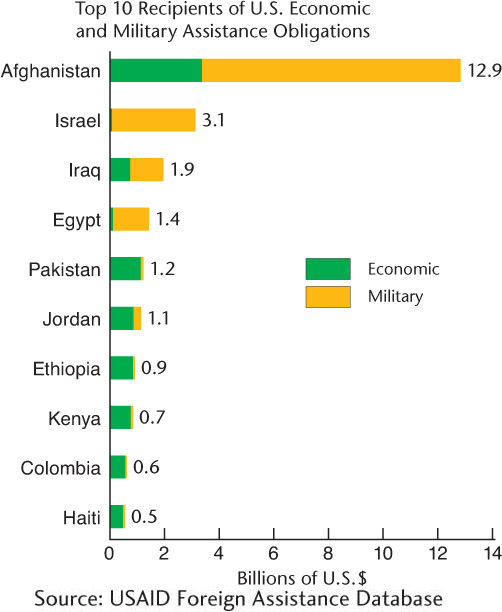

National governments, both individually and working together, are also significant development players. Groups of countries, particularly wealthy ones such as member nations of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) or the Group of 8 (G-8), have been very influential in shaping the course of economic development through promoting international trade. Individual nations also have played decisive roles thanks to their economic might as well as their political influence. Though the United States gives more total foreign aid than any other country in the world—around $50 billion per year—other countries dispense much more on a per capita basis. In 2011 direct assistance to other countries from the United States stood at $97 per capita, while Norway gave $936 per capita and Canada $150 per capita. The world average was $134 per capita (Figure 9.12). The United States has been criticized for channeling much of its international development assistance toward promoting its foreign policy agenda and supporting military and political allies around the world (Figure 9.13).

378

Corporations can be significant development agents as well. Business Insider recently noted that if Walmart were a country, its revenues would be equivalent to the GDP of the 25th largest national economy in the world. In other words, Walmart would be bigger than Norway, Exxon Mobil would be larger than Thailand, General Electric would outrank New Zealand, and Apple would come in ahead of Ecuador. Of course, corporations are not countries and in some important ways the comparison is an unfair one. Yet, the analogy does a good job of highlighting just how economically powerful corporations can be. Some corporations are noted for their development-related investments, which are framed as an aspect of corporate social responsibility. Walmart, for instance, gave cash and in-kind (primarily food) donations nationally and internationally in 2012 amounting to over a billion dollars, or 4.5 percent of its pretax profits for 2011. While corporate leaders argue that national governments and NGOs have until now done little to alleviate poverty and provide basic needs, their critics accuse corporations of being interested in donating solely in order to grow their market share and brand loyalty in impoverished places.

379

Individuals associated with corporations can also become quite active in the arena of international development. Perhaps the most recognizable illustration of this is Bill Gates, who amassed a multibillion dollar fortune as co-founder of Microsoft. Now the head of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, he directs his energy and wealth toward supporting development efforts aimed at alleviating poverty and disease and promoting education globally. In 2008 investment guru Warren Buffett pledged multiple billions to the foundation. He was at the time the world’s wealthiest individual. Buffett and Gates are the first and second most generous philanthropists in the United States, respectively (Figure 9.14). Here, criticisms focus on the individuals’ motivations for giving; namely, tax breaks.

Despite the criticisms, all of these development actors are “on the radar.” In other words, they are visible, recognized, and legitimate participants in the development enterprise. But, it is important to know that there are development actors and activities that are not sanctioned or recognized. For instance, Mexico’s drug lords consider themselves to be the primary source of development aid to regions of the country that have been neglected by the Mexican government for many years. In some states, such as Sinaloa, drug cartels have long based their activities both as producers of locally grown marijuana and heroin, and traffickers for these drugs and for cocaine from South America. Drug lords are often the only investors concerned with building local schools, parks, and infrastructure in rural areas. In 2012 one Sinaloa cartel kingpin, Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzmán, was ranked at #63 on Forbes’s list of the world’s most powerful people.

Indeed, the story that such cartels tell the local people who grow and traffic narcotics on their behalf is that they are merely taking from the wealthy, drug-addicted gringos and giving back to Mexico’s forgotten poor. In other words, drug lords paint themselves as Robin Hood figures enacting social justice on behalf of the downtrodden. It is a powerful narrative, told in quasi-religious terms through the patron saint of narcotraffickers, Jesus Malverde, and in the lyrics of so-called narco-corridos: traditional Mexican ballads (corridos) singing the praises of drug lords.

It is important to emphasize that acknowledging how drug cartels and kingpins have channeled some of their wealth into local development activities in the places where they operate is not the same as condoning these activities. Indeed, Mexico’s drug cartels are engaged in some of the most violent criminal behavior ever seen, seriously threatening the rule of law. Yet it is worth asking, are the sorts of criticisms leveled at the drug lords in some ways similar to those directed at legitimate development actors? More broadly, is development just about helping people, or is it also about controlling them? Finally, and importantly for you as students of geography, what is the future role of powerful and wealthy countries as the world’s primary development actors? The emergence of development alliances among countries that were formerly the recipients of development aid, discussed under Globalization, provides yet another example of how the contemporary regional geographies of development are changing.

380