Preface

To confine our attention to terrestrial matters would be to limit the human spirit.

–STEPHEN HAWKING

Our knowledge about the universe is expanding at a phenomenal rate. New discoveries are being made in many astronomical realms: astronomers are probing the extent of water on the Moon, developing new theories of how the solar system formed, finding planets orbiting numerous stars, and discovering stars and stellar remnants with unexpected properties, among myriad other things.

Many of these scientific updates are included in this edition. I am also pleased to include a wide variety of modern learning techniques and new features in the tenth edition of Discovering the Universe while still providing the wide range of factual topics that are a hallmark of this text.

In the realm of astronomy education, educators continue to develop methods to help students understand how to think like scientists and grasp the core concepts, even when scientific theories are at odds with students’ prior beliefs and misconceptions. In-class interactivities, such as students responding to questions with “clickers,” enrich the classroom experience. Online materials provide tutorials and practice questions that turn students from passive into active learners.

The tenth edition of Discovering the Universe continues to present concepts clearly and accurately to students, while strengthening the pedagogical tools to make the learning process even more worthwhile. The pedagogy includes:

- presenting the observations and underlying physical concepts needed to connect astronomical observations to theories that explain them coherently and meaningfully;

- using both textual and graphical information to present concepts for students who learn in different ways;

- addressing student misconceptions in a respectful but rigorous manner, helping readers to understand why modern scientific views are correct;

- using analogies from everyday life to make cosmic phenomena more concrete;

- providing visually rich timelines that connect astronomical discoveries with other events throughout history;

- providing the dates of the lives of all the people introduced in the text to help students relate discoveries to the historical times in which they occurred;

- expanding student perspectives and confronting misconceptions by exploring plausible alternative situations (asking “What if…?” questions);

- pointing students toward cutting-edge research in “Frontiers yet to be discovered” sections;

- linking material presented in the book with enhanced material offered electronically.

Many Features Bring The Universe Into Clearer Focus

What If…? margin questions about important concepts stretch students’ thinking using hypothetical situations. These questions help to correct misconceptions by explaining to students what strange effects and consequences would result if their initial misconceptions were true.

New theory of planet formation Chapter 5 now presents the Nice (pronounced niece) theory of solar system formation, walking students through a fully up-to-date picture of how the interactions between the Sun and planets evolved. Its effects are discussed in Chapters 6–9.

Margin questions about important concepts are presented in most sections of the book. These questions encourage students to frequently test themselves and correct their beliefs before errors accumulate. For example, after learning about inertia, students are asked how, while driving in a car, they can show that their bodies have inertia. (They could put on the brakes and feel themselves being restrained by the seatbelts.) Answers to approximately one-third of the margin questions appear at the end of this text.

xii

Margin photos provide a connection between the concepts being presented and their applications in everyday life.

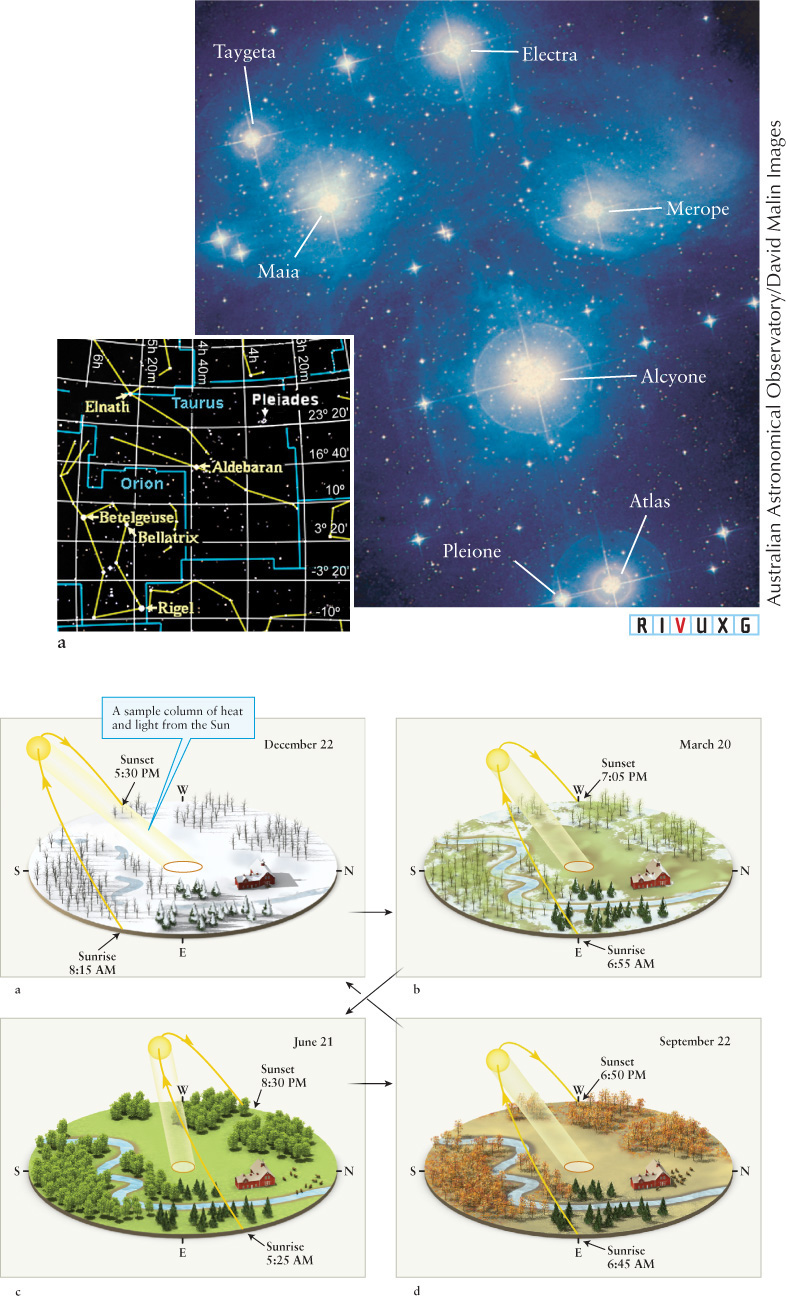

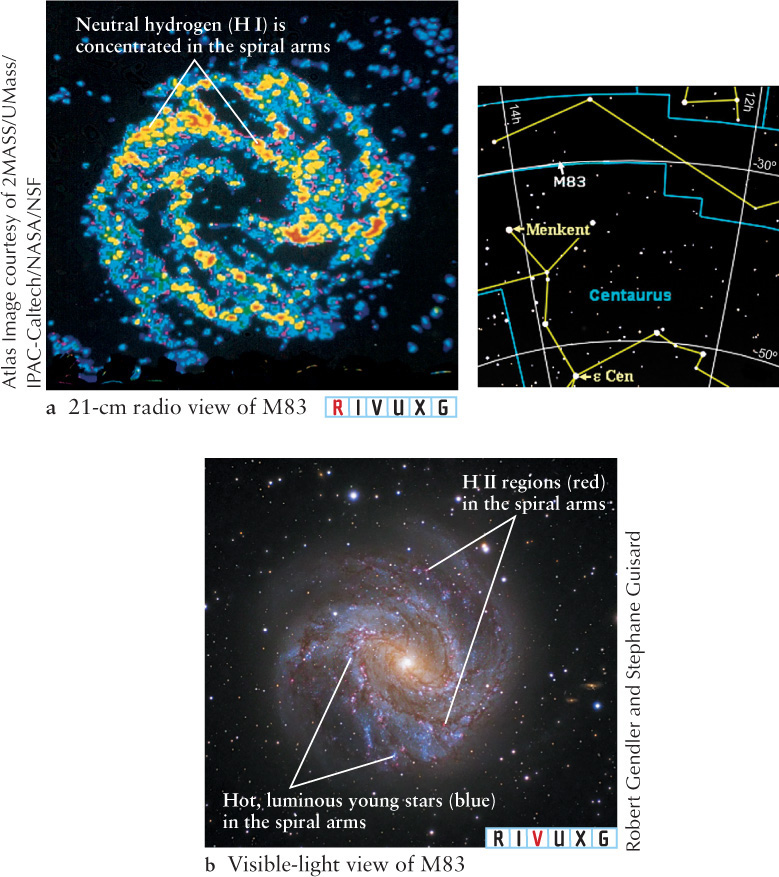

Margin charts show the location in the sky of important astronomical objects cited in the text. Sufficient detail in the margin charts allows students to locate the objects with either the unaided eye or a small telescope, as appropriate. In this example, an image of the Pleiades star cluster is shown with a star chart of the constellation Aldebaran, in which it lies, among other constellations.

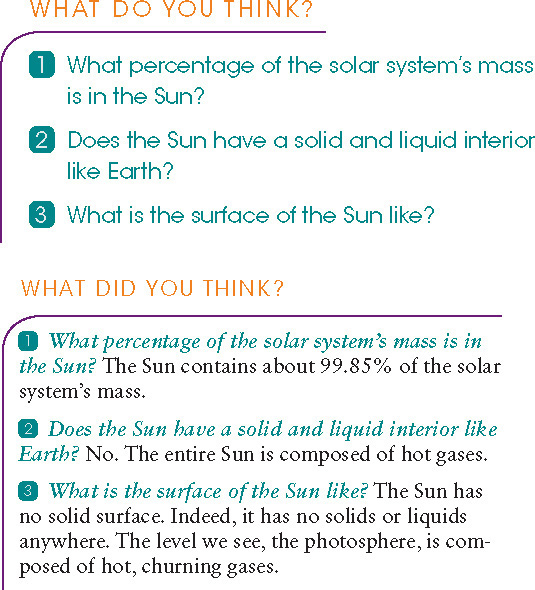

Dynamic art Summary figures appear throughout the book to show either the interactions between important concepts or the evolution of important objects. For example, the location of the Sun in the sky, which varies over the seasons, as does the corresponding intensity of the light and the appropriate ground cover, is shown in a sequence of drawings combined into one figure.

Revised coverage of planet classification The categories of planets, dwarf planets, and small solar system objects are explained and reconciled with the existing classes of objects, including planets, moons, asteroids, meteoroids, and comets. Also explained is how Pluto fits more comfortably with the dwarf planets than with the eight planets.

Deeper focus on fundamental student understanding Discovering the Universe is well known for the clarity of its exposition, but that doesn’t mean we can’t do better. In this edition, a variety of concepts have been fine-tuned to help students better understand them. Some of these are misconception-rich subjects, while others are topics that require exquisite attention to words with multiple meanings.

Proven Features Support Learning

What Do You Think? and What Did You Think? questions in each chapter ask students to consider their present beliefs and actively compare them with the correct science presented in the book. Numbered icons mark the places in the text where each concept is discussed. Encouraging students to think about what they believe is true and then work through the correct science step-by-step has proved to be an effective teaching technique, especially when time constraints prevent instructors from working with students individually or in small groups as they try to reconcile incorrect beliefs with proper science.

xiii

Chapter opening narratives introduce and launch the chapter’s topics and provide students with a context for understanding the material.

Learning objectives underscore the key chapter concepts.

Section headings are brief sentences that summarize section content and serve as a quick study guide to the chapter when reread.

Icons link the text to Web material

Starry Night™ icons link the text to a specific interactivity in the Starry Night™ observing programs.

Starry Night™ icons link the text to a specific interactivity in the Starry Night™ observing programs. Video icons link the text to relevant video clips available on the textbook’s Web site.

Video icons link the text to relevant video clips available on the textbook’s Web site. Animation icons link the text to animated figures available on the textbook’s Web site.

Animation icons link the text to animated figures available on the textbook’s Web site.

Guided Discovery boxes offer hands-on experience with astronomy. Several use the Starry Night™ software.

An Astronomer’s Toolbox introduces some of the algebraic equations used in astronomy. Most of the material in the book is descriptive, so essential equations are set off in numbered boxes to maintain the flow of the material. The toolboxes also contain worked examples, additional explanations, and practice doing calculations; answers are given at the end of the book. All the equations are summarized in Appendix C.

xiv

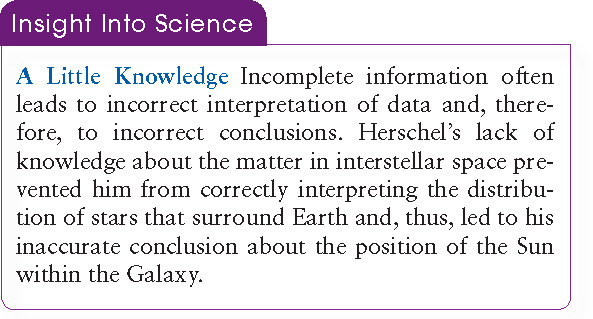

Insight Into Science boxes are brief asides that relate topics to the nature of scientific inquiry and encourage critical thinking.

Wavelength tabs with photographic images show whether an image was made with radio waves (R), infrared radiation (I), visible light (V), ultraviolet light (U), X-rays (X), or gamma rays (G).

Review and practice material

- Summary of Key Ideas is a bulleted list of key concepts.

- What Did You Think? questions at the end of each chapter answer the What Do You Think? questions posed at the beginning of the chapter.

- Key Words, Review Questions, and Advanced Questions help students understand the chapter material.

- Discussion Questions offer interesting topics to spark lively, insightful debate.

- Web Questions take students to the Web for further study.

- NEW: Got It? Questions ask students about either big picture concepts related to the chapter or questions associated with common misconceptions about that material (or both!).

- Observing Projects, featuring Starry Night™ activities, ask students to be astronomers themselves.

What If… Selected chapters conclude with a “What If…” essay that encourages critical thinking by speculating on how changes in the universe could have profound effects on Earth.

An Astronomer’s Almanac, a dynamic timeline that relates discoveries in astronomy to other historical events, opens each of the four Parts of the text. These almanacs provide strong context for the information presented.

Multimedia

FOR STUDENTS

Electronic Versions

Discovering the Universe is offered in two electronic versions. One is an Interactive e-Book, available as part of LaunchPad, described below. The other is a PDF-based e-Book from CourseSmart, available through www.coursesmart.com. These options are provided to offer students and instructors flexibility in their use of course materials.

CourseSmart e-Book

Discovering the Universe CourseSmart e-Book offers the complete text in an easy-to-use, flexible format. Students can choose to view the CourseSmart e-Book online or to download it to their computer or a mobile device, such as iPad, iPhone, or Android device. To help students study and mirror the experience of a printed textbook, CourseSmart e-Books feature notetaking, highlighting, and bookmark features.

ONLINE LEARNING OPTIONS

Discovering the Universe supports instructors with a variety of online learning preferences. Its rich array of resources and platforms provides solutions according to each instructor’s teaching method. Students can also access resources through the Companion Web Site.

LaunchPad: Because Technology Should Never Get in the Way

At W. H. Freeman, we are committed to providing online instructional materials that meet the needs of instructors and students in powerful, yet simple ways—powerful enough to dramatically enhance teaching and learning, yet simple enough to use right away.

xv

We have taken what we’ve learned from thousands of instructors and hundreds of thousands of students to create a new generation of technology: LaunchPad. LaunchPad offers our acclaimed content curated and organized for easy assignment in a breakthrough user interface in which power and simplicity go hand in hand.

Curated LaunchPad units make class prep a whole lot easier

Combining a curated collection of video, tutorials, animations, projects, multimedia activities and exercises, and e-Book content, LaunchPad’s interactive units give instructors building blocks to use as is or as a starting point for their own learning units. An entire unit’s worth of work can be assigned in seconds, drastically saving the amount of time it takes to have the course up and running.

LearningCurve

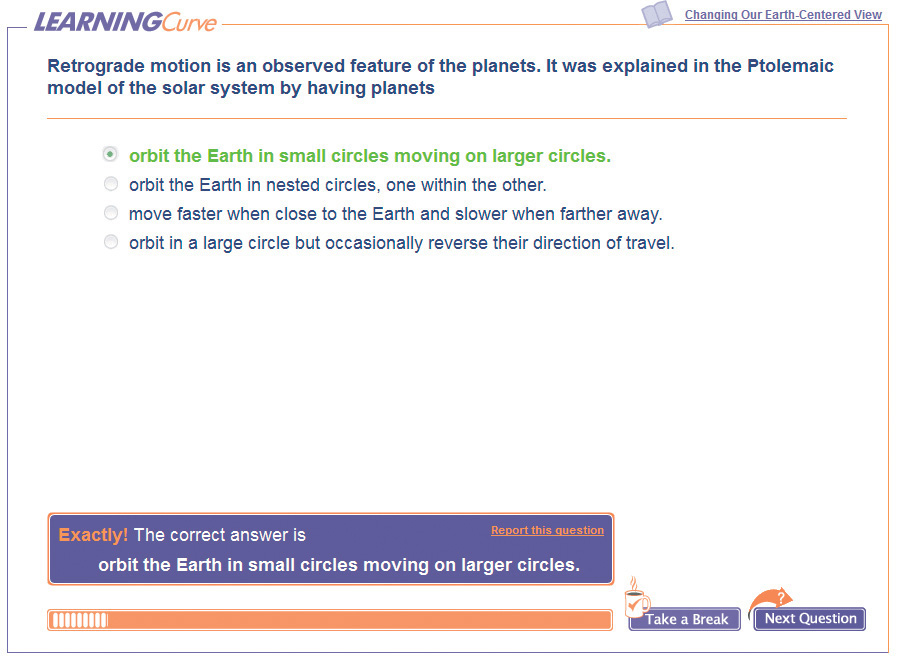

- Powerful adaptive quizzing, a gamelike format, direct links to the e-Book, instant feedback, and the promise of better grades make using LearningCurve a no-brainer.

- Customized quizzing tailored to the text adapts to students’ responses and provides material at different difficulty levels and topics based on student performance. Students love the simple yet powerful system, and instructors can access class reports to help refine lecture content.

xvi

Interactive e-Book

The Interactive e-Book is a complete online version of the textbook with easy access to rich multimedia resources. All text, graphics, tables, boxes, and end-of-chapter resources are included in the e-Book, and the e-Book provides instructors and students with powerful functionality to tailor their course resources to fit their needs.

- Quick, intuitive navigation to any section or subsection

- Full-text search, including the Glossary and Index

- Sticky-note feature allows users to place notes anywhere on the screen, and choose the note color for easy categorization.

- “Top-note” feature allows users to place a prominent note at the top of the page to provide a more significant alert or reminder.

- Text highlighting in a variety of colors

Astronomy Tutorials

These self-guided, concept-driven experiential walkthroughs engage students in the process of scientific discovery as they make observations, draw conclusions, and apply their knowledge. Astronomy tutorials combine multimedia resources, activities, and quizzes.

Image Map Activities

These activities use figures and photographs from the text to assess key ideas, helping students to develop their visual literacy. Students must click the appropriate section(s) of the image and answer corresponding questions.

Animations, Videos, Interactive Exercises, Flashcards

Other LaunchPad resources highlight key concepts in introductory astronomy.

Assignments for Online Quizzing, Homework, and Self-Study

Instructors can create and assign automatically graded homework and quizzes from the complete test bank, which is preloaded in LaunchPad. All quiz results feed directly into the instructor’s gradebook.

Scientific American Newsfeed

To demonstrate the continued process of science and the exciting new developments in astronomy, the Scientific American Newsfeed delivers regularly updated material from the well-known magazine. Articles, podcasts, news briefs, and videos on subjects related to astronomy are selected for inclusion by Scientific American’s editors. The Newsfeed provides several updates per week, and instructors can archive or assign the content they find most valuable.

Gradebook

The included gradebook quickly and easily allows instructors to look up performance metrics for a whole class, for individual students and for individual assignments. Having ready access to this information can help both in lecture prep and in making office hours more productive and efficient.

Sapling Learning

Developed by educators with both online expertise and extensive classroom experience, Sapling Learning provides highly effective interactive homework and instruction that improve student learning outcomes for the problem-solving disciplines. Sapling Learning offers enjoyable teaching and effective learning experiences that are distinctive in three important ways:

- Ease of use: Sapling Learning’s easy-to-use interface keeps students engaged in problem-solving, not struggling with the software.

- Targeted instructional content: Sapling Learning increases student engagement and comprehension by delivering immediate feedback and targeted instructional content.

- Unsurpassed service and support: Sapling Learning makes teaching more enjoyable by providing a dedicated Masters and Ph.D. level colleague to service instructors’ unique needs throughout the course, including content customization.

We offer bundled packages with all versions of our texts that include Sapling Learning Online Homework.

STUDENT COMPANION WEB SITE

The Companion Web site at www.whfreeman.com/dtu10e features a variety of study and review resources designed to help students understand the concepts. The open-access Web site includes the following:

- Online quizzing offers questions and answers with instant feedback to help students study, review, and prepare for exams. Instructors can access results through an online database or they can have results e-mailed directly to their accounts.

- Animations and videos both original and NASA- created, are keyed to specific chapters.

- Flashcards offer help with vocabulary and definitions.

STARRY NIGHT™

Starry Night™ is a brilliantly realistic planetarium software package. It is designed for easy use by anyone with an interest in the night sky. See the sky from anywhere on Earth or lift off and visit any solar system body or any location up to 20,000 light-years away. View 2,500,000 stars along with more than 170 deep-space objects such as galaxies, star clusters, and nebulae. Travel 15,000 years in time, check out the view from the International Space Station, and see planets up close from any one of their moons. Included are stunning OpenGL graphics. Handy star charts can be printed to explore outdoors. A download code for Starry Night™ is available with the text upon request.

xvii

OBSERVING PROJECTS USING STARRY NIGHT™

by T. Alan Clark and William J. F. Wilson, University of Calgary, and Marcel Bergman

ISBN 1-4641-2502-3

Available for packaging with the text and compatible with both PC and Mac, this workbook contains a variety of comprehensive lab activities for use with Starry Night™. The Observing Projects workbook can also be packaged with th Starry Night™ software.

FOR INSTRUCTORS

TEST BANK CD-ROM

Windows and Mac versions on one disc,

ISBN 1-4641-6878-4

More than 3,500 multiple-choice questions are section-referenced. The easy-to-use CD-ROM allows instructors to add, edit, resequence, and print questions to suit their needs.

ONLINE COURSE MATERIALS (BLACKBOARD, MOODLE, SAKAI, CANVAS)

As a service for adopters, we will provide content files in the appropriate online course format, including the instructor and student resources for the textbook. The files can be used as is or can be customized to fit specific needs. Prebuilt quizzes, animations, and activities, among other materials, are included.

CLASSROOM PRESENTATION AND INTERACTIVITY

A set of online lecture presentations created in PowerPoint allows instructors to tailor their lectures to suit their own needs using images and notes from the textbook. These presentations are available on the instructor portion of the companion Web site.

CLICKER QUESTIONS

Written by Neil Comins, these questions can be used as lecture launchers with or without a classroom response system such as iClicker. Each chapter includes questions relating to figures from the text and common misconceptions, as well as writing questions for instructors who would like to add a writing or class discussion element to their lectures.

Acknowledgments

I am deeply grateful to the astronomers and teachers who reviewed the manuscript of this edition. This is a stronger and better book because of their conscientious efforts:

Miah M. Adel, University of Arkansas, Pine Bluff

Steven Ball, LeTourneau University

Kirsten R. Bernabee, Idaho State University

Bruce W. Bridenbecker, Copper Mountain College

Eric Centauri, University of Tulsa

Larry A. Ciupik, Indiana University Northwest

Michael K. Durand, California State University, Dominguez Hills

Gregory J. Falabella, Wagner College

Tim Farris, Volunteer State Community College

Rica Sirbaugh French, MiraCosta College

Wayne K. Guinn, Lon Morris College

Richard Ignace, East Tennessee State University

Alex Ignatiev, University of Houston

Mahmoud Khalili, Northeastern Illinois University

Kevin Krisciunas, Texas A&M University

Peter Lanagan, College of Southern Nevada

Shawn T. Langan, University of Nebraska, Lincoln

James Lauroesch, University of Louisville

Lauren Likkel, University of Wisconsin, Eau Claire

Jane H. MacGibbon, University of North Florida

Melissa A. Morris, Arizona State University

Douglas Nagy, Ursinus College

Christopher Palma, Pennsylvania State University

Billy L. Quarles, University of Texas, Arlington

Susan R. Rolke, Franklin Pierce University

Richard Ross, Rock Valley College

Mehmet Alper Sahiner, Seton Hall University

Kelli Corrado Spangler, Montgomery County Community College

Philip T. Spickler, Bridgewater College

Aaron R. Warren, Purdue University North Central

Lee C. Widmer, Xavier University

I would also like to thank the many people whose advice on previous editions has had an ongoing influence:

John Anderson, University of North Florida

Kurt S. J. Anderson, New Mexico State University

Gordan Baird, University of Arizona

Nadine G. Barlow, Northern Arizona University

Henry E. Bass, University of Mississippi

J. David Batchelor, Community College of Southern Nevada

Jill Bechtold, University of Arizona

Peter A. Becker, George Mason University

Ralph L. Benbow, Northern Illinois University

John Bieging, University of Arizona

xviii

Greg Black, University of Virginia

John C. (Jack) Brandt, University of New Mexico

James S. Brooks, Florida State University

John W. Burns, Mt. San Antonio College

Gene Byrd, University of Alabama

Eugene R. Capriotti, Michigan State University

Eric D. Carlson, Wake Forest University

Jennifer L. Cash, South Carolina State University

Michael W. Castelaz, Pisgah Astronomical Research Institute

Gerald Cecil, University of North Carolina

David S. Chandler, Porterville College

David Chernoff, Cornell University

Erik N. Christensen, South Florida Community College

Tom Christensen, University of Colorado, Colorado Springs

Chris Clemens, University of North Carolina

Christine Clement, University of Toronto

Halden Cohn, Indiana University

John Cowan, University of Oklahoma

Antoinette Cowie, University of Hawaii

Charles Curry, University of Waterloo

James J. D’Amario, Harford Community College

Purnas Das, Purdue University

Peter Dawson, Trent University

John M. Dickey, University of Minnesota, Twin Cities

John D. Eggert, Daytona Beach Community College

Stephen S. Eikenberry, University of Florida

Bernd Enders, College of Marin

Andrew Favia, University of Maine

Rica French, Mira Costa College

Robert Frostick, West Virginia State College

Martin Gaskell, University of Nebraska

Richard E. Griffiths, Carnegie Mellon University

Bruce Gronich, University of Texas, El Paso

Siegbert Hagmann, Kansas State University

Thomasanna C. Hail, University of Mississippi

Javier Hasbun, University of West Georgia

David Hedin, Northern Illinois University

Chuck Higgins, Pennsylvania State University

Scott S. Hildreth, Chabot College

Thomas Hockey, University of Northern Iowa

Mark Hollabaugh, Normandale Community College

J. Christopher Hunt, Prince George’s Community College

James L. Hunt, University of Guelph

Nathan Israeloff, Northeastern College

Francine Jackson, Framingham State College

Fred Jacquin, Onondaga Community College

Kenneth Janes, Boston University

Katie Jore, University of Wisconsin–Steven’s Point

William C. Keel, University of Alabama

William Keller, St. Petersburg Junior College

Marvin D. Kemple, Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis

Pushpa Khare, University of Illinois at Chicago

F. W. Kleinhaus, Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis

Agnes Kim, Georgia College & State University

Rob Klinger, Parkland College

H. S. La, Clayton State University

Patick M. Len, Cuesta College

John Patrick Lestrade, Mississippi State University

C. L. Littler, University of North Texas

M. A. K. Lohdi, Texas Tech University

Michael C. LoPresto, Henry Ford Community College

Phyllis Lugger, Indiana University

R. M. MacQueen, Rhodes College

Robert Manning, Davidson College

Paul Mason, University of Texas, El Paso

P. L. Matheson, Salt Lake Community College

Steve May, Walla Walla Community College

Rahul Mehta, University of Central Arkansas

Ken Menningen, University of Wisconsin–Steven’s Point

J. Scott Miller, University of Louisville

Scott Miller, Pennsylvania State University

L. D. Mitchell, Cambria County Area Community College

J. Ward Moody, Brigham Young University

Siobahn M. Morgan, University of Northern Iowa

Steven Mutz, Scottsdale Community College

Charles Nelson, Drake University

Gerald H. Newsom, Ohio State University

Bob O’Connell, College of the Redwoods

William C. Oelfke, Valencia Community College

Richard P. Olenick, University of Dallas

John P. Oliver, University of Florida

Ron Olowin, St. Mary’s College of California

Melvyn Jay Oremland, Pace University

Jerome A. Orosz, San Diego State University

David Patton, Trent University

Jon Pedicino, College of the Redwoods

Sidney Perkowitz, Emory University

Lawrence Pinsky, University of Houston

Eric Preston, Indiana State University

David D. Reid, Wayne State University

Adam W. Rengstorf, Indiana University

James A. Roberts, University of North Texas

Henry Robinson, Montgomery College

Dwight P. Russell, University of Texas, El Paso

Barbara Ryden, Ohio State University

Itai Seggev, University of Mississippi

Larry Sessions, Metropolitan State University

C. Ian Short, Florida Atlantic University

xix

John D. Silva, University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth

Michael L. Sitko, University of Cincinnati

Earl F. Skelton, University of California at Berkeley

George F. Smoot, University of California at Berkeley

Alex G. Smith, University of Florida

Jack Sulentic, University of Alabama

David Sturm, University of Maine, Orono

Paula Szkody, University of Washington

Michael T. Vaughan, Northeastern University

Andreas Veh, Kenai Peninsula College

John Wallin, George Mason University

William F. Welsh, San Diego State University

R. M. Williamon, Emory University

Gerard Williger, University of Louisville

J. Wayne Wooten, Pensacola Junior College

Edward L. (Ned) Wright, University of California at Los Angeles

Jeff S. Wright, Elon College

Nicolle E. B. Zellner, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute

I would like to add my special thanks to the wonderfully supportive staff at W. H. Freeman and Company who make the revision process so enjoyable. Among others, these people include Jessica Fiorillo, Alicia Brady, Brittany Murphy, Kerry O’Shaughnessy, Courtney Lyons, Amy Thorne, Victoria Tomaselli, Sheena Goldstein, Matt McAdams, and Susan Wein. Thanks also go to my copyeditor and indexer, Louise Ketz, and proofreader, Patti Brecht. Thank you to T. Alan Clark, Marcel W. Bergman, and William J. F. Wilson for their work on the Starry Night™ material. Warm thanks also to David Sturm, University of Maine, Orono, for his help in collecting current data on objects in the solar system; to my graduate student, Andrej Favia, for his expert work on identifying, categorizing, and addressing misconceptions about astronomy; to my UM astronomy colleague David Batuski; and to my wife, Sue, for her patience and support while preparing this book.

Neil F. Comins

xx

xxi