Chapter 2. Chapter 2: Science Literacy and the Process of Science

What is information literacy...

Guiding Question 2.5

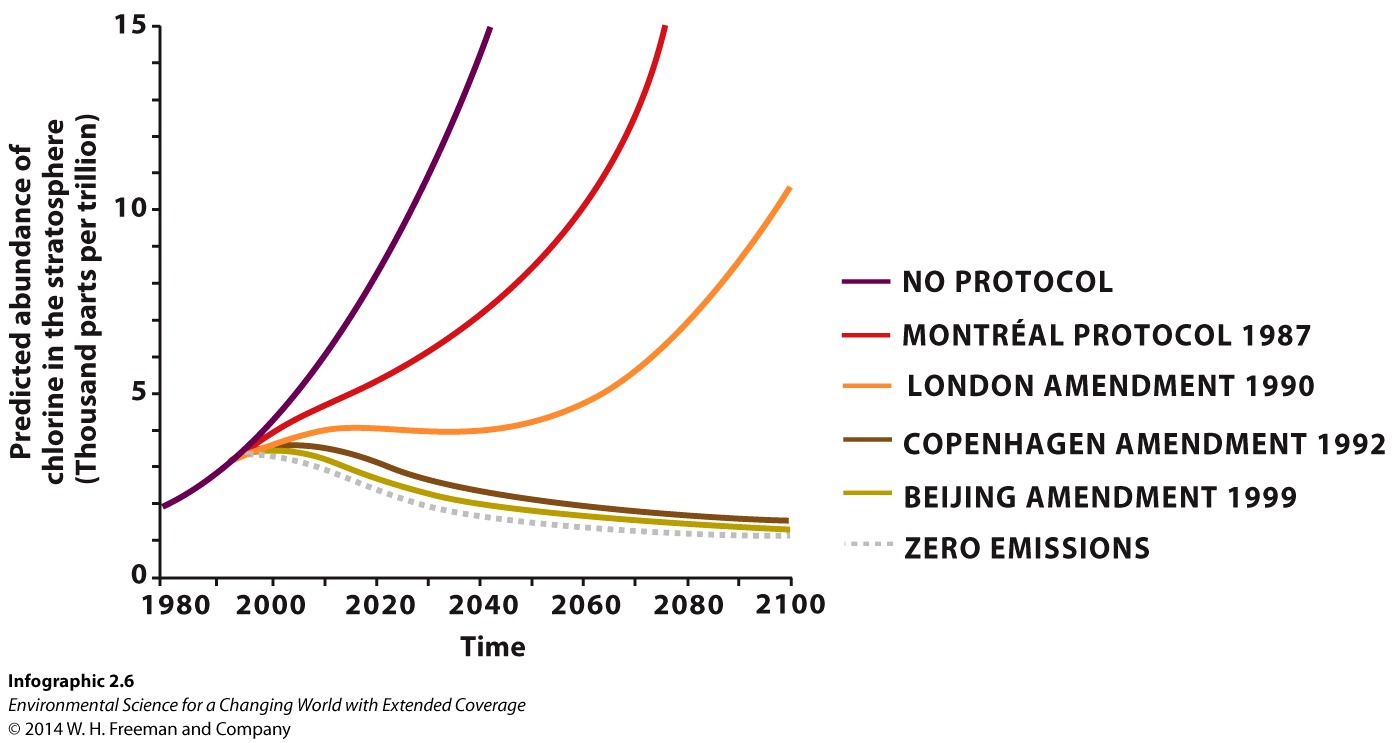

How did scientists, policy makers, and world leaders take the science about ozone depletion and turn it into policy?

Why You Should Care

As with experts in any field, scientists often have a difficult time getting non-experts to understand the value and implications of their findings. The Montréal Protocol is one of the best examples of scientists succeeding at using evidence to lead to policy changes that are helping a negative situation.

Test Your Vocabulary

Choose the correct term for each of the following definitions:

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Plan that allows room for altering strategies as new information comes in or the situation itself changes. | |

| Acting in a way that leaves a safety margin when the data are uncertain or severe consequences are possible. | |

| A formalized plan that addresses a desired outcome or goal. | |

| A plan to deal with the problem of ozone depletion, most notably by phasing out the use of dangerous chemicals such as CFCs. | |

| The mathematical evaluation of experimental data to determine how likely it is that any difference observed is due to the variable being tested. |

Question Sequence

1.

Why is the plan for reducing CFC production called the Montréal Protocol, and why are all of its amendments also named after cities?

2.

What role did the precautionary principle have to play in the adoption of the Montréal Protocol?

3.

Why is there more than one line for ozone depletion in this graph?

4.

How do you think scientists came up with the different predictions for ozone depletion?

5.

Is there any way to know for certain now if the various amendments to the Montréal Protocol will reduce ozone-depleting gases by the end of the century? Why?

Short-Answer Questions

Similar to the findings that CFCs released by human activity into the atmosphere coincided with depletion of the ozone layer, atmospheric scientists have also discovered a relationship between the human release of so-called "greenhouse gases," such as carbon dioxide and methane, and an average increase in global temperature. Like the Montréal Protocol, the Kyoto Protocol was an international compact to reduce emissions of these gases, but unlike the Montréal Protocol, it was never ratified by enough countries to make it a viable agreement.

1) Why do you think that some countries did not ratify the Kyoto Protocol if there was scientific evidence to indicate that reducing greenhouse-gas emissions would prevent further global climate change?

2) Is the case of the Kyoto Protocol an example of using the precautionary principle? Why or why not?

3) The evidence linking greenhouse-gas emissions to climate change is mostly based on observational studies. Do you think countries would be more likely to act on greenhouse-gas limits if there were experimental evidence as well? Why?

4) Some experts are of the opinion that the way the scientists conduct science and refer to their work makes it difficult for public-policy makers to change laws based on the scientists’ findings. Do you think this is true? Why?

2. Yes, those involved decided that the evidence of potential negative repercussions was conclusive enough that action should be taken.

3. Experiments do show causation more clearly than observational studies, so the short answer is yes, experimental evidence would likely be more convincing. That being said, it is difficult to impossible to experiment on a scale large enough to simulate the atmosphere, so any experiment used to show human-influenced global climate change could potentially be as suspect as the current observational studies. Furthermore, you have learned that there is often a disconnect between science and public policy. A legislature with political reasons not to act is apt to ignore any evidence that isn't 100% conclusive, which (as you have learned) doesn't happen in science.

4. There are many examples of this, but a notable obstacle is the perception that science "proves" something.

Activity results are being submitted...