MLA-style project (David Craig)

Craig 1

David Craig

Professor Turkman

English 219

8 December 2011

Messaging: The Language of Youth Literacy

The English language is under attack. At least, that is what many people seem to believe. From concerned parents to local librarians, everyone seems to have a negative comment on the state of youth literacy today. They fear that the current generation of grade school students will graduate with an extremely low level of literacy, and they point out that although language education hasn’t changed, kids are having more trouble reading and writing than in the past. When asked about the cause of this situation, many adults pin the blame on technologies such as texting and instant messaging, arguing that electronic shortcuts create and compound undesirable reading and writing habits and discourage students from learning conventionally correct ways to use language. But although the arguments against messaging are passionate, evidence suggests that they may not hold up.

The disagreements about messaging shortcuts are profound, even among academics. John Briggs, an English professor at the University of California, Riverside, says, “Americans have always been informal, but now the informality of precollege culture is so ubiquitous that many students have no practice in using language in any formal setting at all” (qtd. in McCarroll). Such objections are not new; Sven Birkerts of Mount Holyoke College argued in 1999 that “[students] read more casually. They strip-mine what they read” online and consequently produce “quickly generated, casual prose” (qtd. in Leibowitz A67). However, academics are also among the defenders of texting and instant messaging (IM), with some suggesting that messaging may be a beneficial force in the development of youth literacy because it promotes regular contact with words and the use of a written medium for communication.

Texting and instant messaging allow two individuals who are separated by any distance to engage in real-time, written communication.

Craig 2

Although such communication relies on the written word, many messagers disregard standard writing conventions. For example, here is a snippet from an IM conversation between two teenage girls:1

Teen One: sorry im talkinto like 10 ppl at a time

Teen Two: u izzyful person

Teen Two: kwel

Teen One: hey i g2g

As this brief conversation shows, participants must use words to communicate via texting and messaging, but their words do not have to be in standard English.

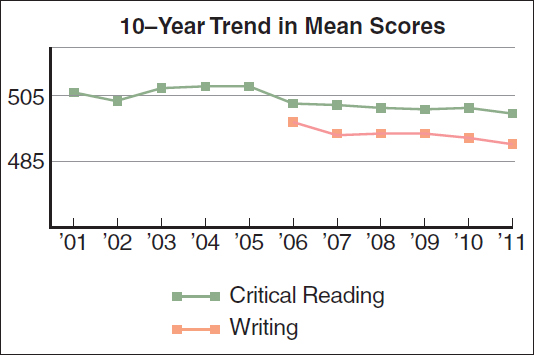

The issue of youth literacy does demand attention because standardized test scores for language assessments, such as the verbal and writing sections of the College Board’s SAT, have declined in recent years. This trend is illustrated in a chart distributed by the College Board as part of its 2011 analysis of aggregate SAT data (see Fig. 1).

The trend lines illustrate a significant pattern that may lead to the conclusion that youth literacy is on the decline. These lines display the ten-year paths (from 2001 to 2011) of reading and writing scores, respectively. Within this period, the average verbal score dropped a few points—and appears to be headed toward a further decline in the future.

1. This transcript of an IM conversation was collected on 20 Nov. 2011. The teenagers’ names are concealed to protect privacy

Craig 3

Based on the preceding statistics, parents and educators appear to be right about the decline in youth literacy. And this trend coincides with another phenomenon: digital communication is rising among the young. According to the Pew Internet & American Life Project, 85 percent of those aged 12-17 at least occasionally write text messages, instant messages, or comments on social networking sites (Lenhart, Arafeh, Smith, and Macgill). In 2001, the most conservative estimate based on Pew numbers showed that American youths spent, at a minimum, nearly three million hours per day on messaging services (Lenhart and Lewis 20). These numbers are now exploding thanks to texting, which was “the dominant daily mode of communication” for teens in 2012 (Lenhart), and messaging on popular social networking sites such as Facebook and Tumblr.

In the interest of establishing the existence of a messaging language, I analyzed 11,341 lines of text from IM conversations between youths in my target demographic: U.S. residents aged twelve to seventeen. Young messagers voluntarily sent me chat logs, but they were unaware of the exact nature of my research. Once all of the logs had been gathered, I went through them, recording the number of times messaging language was used in place of conventional words and phrases. Then I generated graphs to display how often these replacements were used.

During the course of my study, I identified four types of messaging language: phonetic replacements, acronyms, abbreviations, and inanities. An example of phonetic replacement is using ur for you are. Another popular type of messaging language is the acronym; for a majority of the people in my study, the most common acronym was lol, a construction that means laughing out loud. Abbreviations are also common in messaging, but I discovered that typical IM abbreviations, such as etc., are not new to the English language. Finally, I found a class of words that I call “inanities.” These words include completely new words or expressions, combinations of several slang categories, or simply nonsensical variations of other words.

Craig 4

My favorite from this category is lolz, an inanity that translates directly to lol yet includes a terminating z for no obvious reason.

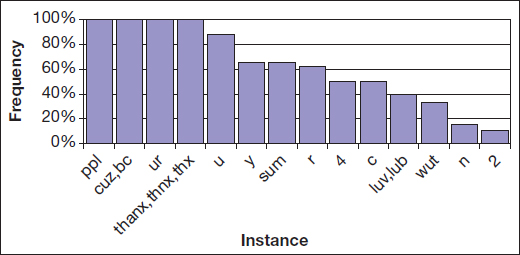

In the chat transcripts that I analyzed, the best display of typical messaging lingo came from the conversations between two thirteen-year-old Texan girls, who are avid IM users. Figure 2 is a graph showing how often they used certain phonetic replacements and abbreviations. On the y-axis, frequency of replacement is plotted, a calculation that compares the number of times a word or phrase is used in messaging language with the total number of times that it is communicated in any form. On the x-axis, specific messaging words and phrases are listed.

My research shows that the Texan girls use the first ten phonetic replacements or abbreviations at least 50 percent of the time in their normal messaging writing. For example, every time one of them writes see, there is a parallel time when c is used in its place. In light of this finding, it appears that the popular messaging culture contains at least some elements of its own language. It also seems that much of this language is new: no formal dictionary yet identifies the most common messaging words and phrases. Only in the heyday of the telegraph or on the rolls of a stenographer would you find a similar situation, but these “languages” were never a popular medium of youth communication. Texting and instant messaging, however, are very popular among young people and continue to generate attention and debate in academic circles.

Craig 5

My research shows that messaging is certainly widespread, and it does seem to have its own particular vocabulary, yet these two factors alone do not mean it has a damaging influence on youth literacy. As noted earlier, however, some people claim that the new technology is a threat to the English language. In an article provocatively titled “Texting Makes U Stupid,” historian Niall Ferguson argues, “The good news is that today’s teenagers are avid readers and prolific writers. The bad news is that what they are reading and writing are text messages.” He goes on to accuse texting of causing the United States to “[fall] behind more-literate societies.”

The critics of messaging are numerous. But if we look to the field of linguistics, a central concept—metalinguistics—challenges these criticisms and leads to a more reasonable conclusion—that messaging has no negative impact on a student’s development of or proficiency with traditional literacy.

Scholars of metalinguistics offer support for the claim that messaging is not damaging to those who use it. As noted earlier, one of the most prominent components of messaging language is phonetic replacement, in which a word such as everyone becomes every1. This type of wordplay has a special importance in the development of an advanced literacy, and for good reason. According to David Crystal, an internationally recognized scholar of linguistics at the University of Wales, as young children develop and learn how words string together to express ideas, they go through many phases of language play. The singsong rhymes and nonsensical chants of preschoolers are vital to their learning language, and a healthy appetite for such wordplay leads to a better command of language later in life (182).

As justification for his view of the connection between language play and advanced literacy, Crystal presents an argument for metalinguistic awareness. According to Crystal, metalinguistics refers to the ability to “step back” and use words to analyze how language works:

Craig 6

If we are good at stepping back, at thinking in a more abstract way about what we hear and what we say, then we are more likely to be good at acquiring those skills which depend on just such a stepping back in order to be successful—and this means, chiefly, reading and writing. … [T]he greater our ability to play with language, … the more advanced will be our command of language as a whole. (Crystal 181)

If we accept the findings of linguists such as Crystal that metalinguistic awareness leads to increased literacy, then it seems reasonable to argue that the phonetic language of messaging can also lead to increased metalinguistic awareness and, therefore, increases in overall literacy. As messagers develop proficiency with a variety of phonetic replacements and other types of texting and messaging words, they should increase their subconscious knowledge of metalinguistics.

Metalinguistics also involves our ability to write in a variety of distinct styles and tones. Yet in the debate over messaging and literacy, many critics assume that either messaging or academic literacy will eventually win out in a person and that the two modes cannot exist side by side. This assumption is, however, false. Human beings ordinarily develop a large range of language abilities, from the formal to the relaxed and from the mainstream to the subcultural. Mark Twain, for example, had an understanding of local speech that he employed when writing dialogue for Huckleberry Finn. Yet few people would argue that Twain’s knowledge of this form of English had a negative impact on his ability to write in standard English.

However, just as Mark Twain used dialects carefully in dialogue, writers must pay careful attention to the kind of language they use in any setting. The owner of the language Web site The Discouraging Word, who is an anonymous English literature graduate student at the University of Chicago, backs up this idea in an e-mail to me:

What is necessary, we feel, is that students learn how to shift between different styles of writing—that, in other words, the abbreviations and shortcuts of messaging should be used online … but that they should not be used in an essay submitted to a teacher. … Messaging might even be considered … a different way of reading and writing, one that requires specific and unique skills shared by certain communities.

Craig 7

The analytical ability that is necessary for writers to choose an appropriate tone and style in their writing is, of course, metalinguistic in nature because it involves the comparison of two or more language systems. Thus, youths who grasp multiple languages will have a greater natural understanding of metalinguistics. More specifically, young people who possess both messaging and traditional skills stand to be better off than their peers who have been trained only in traditional or conventional systems. Far from being hurt by their online pastime, instant messagers can be aided in standard writing by their experience with messaging language.

The fact remains, however, that youth literacy seems to be declining. What, if not messaging, is the main cause of this phenomenon? According to the College Board, which collects data on several questions from its test takers, course work in English composition and grammar classes decreased by 14 percent between 1992 and 2002 (Carnahan and Coletti 11). The possibility of messaging causing a decline in literacy seems inadequate when statistics on English education for US youths provide other evidence of the possible causes. Simply put, schools in the United States are not teaching English as much as they used to. Rather than blaming texting and messaging language alone for the decline in literacy and test scores, we must also look toward our schools’ lack of focus on the teaching of standard English skills.

My findings indicate that the use of messaging poses virtually no threat to the development or maintenance of formal language skills among American youths aged twelve to seventeen. Diverse language skills tend to increase a person’s metalinguistic awareness and, thereby, his or her ability to use language effectively to achieve a desired purpose in a particular situation. The current decline in youth literacy is not due to the rise of texting and messaging. Rather, fewer young students seem to be receiving an adequate education in the use of conventional English. Unfortunately, it may always be fashionable to blame new tools for old problems, but in the case of messaging, that blame is not warranted. Although messaging may expose literacy problems, it does not create them.

Craig 8

Works Cited

Carnahan, Kristin, and Chiara Coletti. Ten-Year Trend in SAT Scores Indicates Increased Emphasis on Math Is Yielding Results: Reading and Writing Are Causes for Concern. New York: College Board, 2002. Print.

College Board. “2011 SAT Trends.” Collegeboard.org. College Board, 14 Sept. 2011. Web. 6 Dec. 2012.

Crystal, David. Language Play. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1998. Print.

The Discouraging Word. “Re: Messaging and Literacy.” Message to the author. 13 Nov. 2012. E-mail.

Ferguson, Niall. “Texting Makes U Stupid.” Newsweek 158.12 (2011): 11. Academic Search Premier. Web. 7 Dec. 2012.

Leibowitz, Wendy R. “Technology Transforms Writing and the Teaching of Writing.” Chronicle of Higher Education 26 Nov. 1999: A67-68. Print.

Lenhart, Amanda. Teens, Smartphones, & Texting. Pew Research Center’s Internet & Amer. Life Project, 19 Mar. 2012. PDF file.

Lenhart, Amanda, Sousan Arafeh, Aaron Smith, and Alexandra Macgill. Writing, Technology & Teens. Pew Research Center’s Internet & Amer. Life Project, 24 Apr. 2008. PDF file.

Lenhart, Amanda, and Oliver Lewis. Teenage Life Online: The Rise of the Instant-Message Generation and the Internet’s Impact on Friendships and Family Relationships. Pew Research Center’s Internet & Amer. Life Project, 21 June 2001. PDF file.

McCarroll, Christina. “Teens Ready to Prove Text-Messaging Skills Can Score SAT Points.” Christian Science Monitor 11 Mar. 2005. Web. 10 Dec. 2012.