Occasions for Argument

Occasions for Argument

In a fifth-century BCE textbook of rhetoric (the art of persuasion), the philosopher Aristotle provides an ingenious strategy for classifying arguments based on their perspective on time — past, future, and present. His ideas still help us to appreciate the role arguments play in society in the twenty-first century. As you consider Aristotle’s occasions for argument, remember that all such classifications overlap (to a certain extent) and that we live in a world much different than his.

Arguments about the Past

Debates about what has happened in the past, what Aristotle called forensic arguments, are the red meat of government, courts, businesses, and academia. People want to know who did what in the past, for what reasons, and with what liability. When you argue a speeding ticket in court, you are making a forensic argument, claiming perhaps that you weren’t over the limit or that the officer’s radar was faulty. A judge will have to decide what exactly happened in the past in the unlikely case you push the issue that far.

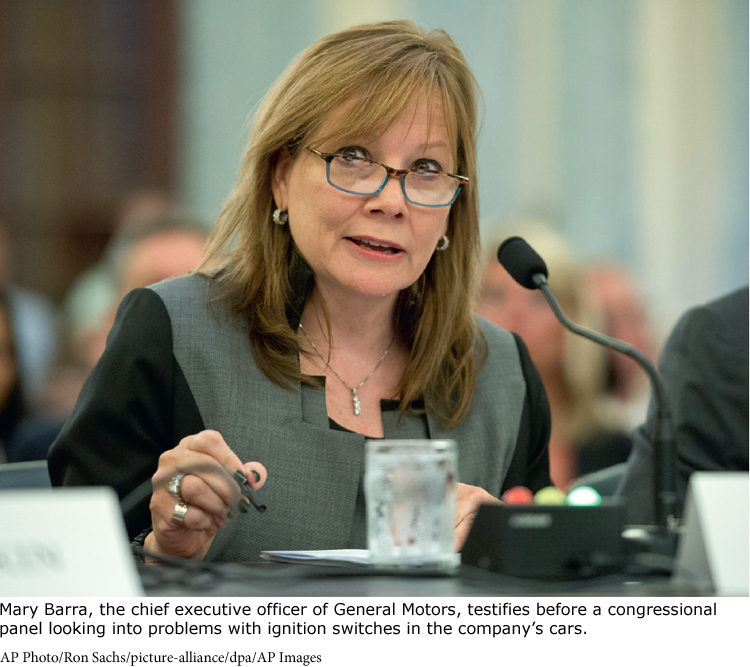

More consequentially, in 2014 the federal government and General Motors found themselves deeply involved in arguments about the past as investigators sought to determine just exactly how the massive auto company had allowed a serious defect in the ignition switches of its cars to go undisclosed and uncorrected for a decade. Drivers and passengers died or were injured as engines shut down and airbags failed to go off in subsequent collisions. Who at General Motors was responsible for not diagnosing the fault? Were any engineers or executives liable for covering up the problem? And how should victims of this product defect or their families be compensated? These were all forensic questions to be thoroughly investigated, argued, and answered by regulatory panels and courts.

From an academic perspective, consider the lingering forensic arguments over Christopher Columbus’s “discovery” of America. Are his expeditions cause for celebration or notably unhappy chapters in human history? Or some of both? Such arguments about past actions — heated enough to spill over into the public realm — are common in disciplines such as history, philosophy, and ethics.

Amy Davidson’s article “Four Ways the Riley Ruling Matters for the NSA” predicts some probable outcomes of an important Supreme Court decision.

Arguments about the Future

Debates about what will or should happen in the future — deliberative arguments — often influence policies or legislation for the future. Should local or state governments allow or even encourage the use of self-driving cars on public roads? Should colleges and universities lend support to more dual-credit programs so that students can earn college credits while still in high school? Should coal-fired power plants be phased out of our energy grid? These are the sorts of deliberative questions that legislatures, committees, or school boards routinely address when making laws or establishing policies.

But arguments about the future can also be speculative, advancing by means of projections and reasoned guesses, as shown in the following passage from an essay by media maven Marc Prensky. He is arguing that it is time for some college or university to be the first to ban physical, that is to say paper, books on its campus, a controversial proposal to say the least:

Colleges and professors exist, in great measure, to help “liberate” and connect the knowledge and ideas in books. We should certainly pass on to our students the ability to do this. But in the future those liberated ideas — the ones in the books (the author’s words), and the ones about the books (the reader’s own notes, all readers’ thoughts and commentaries) — should be available with a few keystrokes. So, as counterintuitive as it may sound, eliminating physical books from college campuses would be a positive step for our 21st-century students, and, I believe, for 21st-century scholarship as well. Academics, researchers, and particularly teachers need to move to the tools of the future. Artifacts belong in museums, not in our institutions of higher learning.

— Marc Prensky, “In the 21st-Century University, Let’s Ban Books”

Arguments about the Present

Arguments about the present — what Aristotle terms epideictic or ceremonial arguments — explore the current values of a society, affirming or challenging its widely shared beliefs and core assumptions. Epideictic arguments are often made at public and formal events such as inaugural addresses, sermons, eulogies, memorials, and graduation speeches. Members of the audience listen carefully as credible speakers share their wisdom. For example, as the selection of college commencement speakers has grown increasingly contentious, Ruth J. Simmons, the first African American woman to head an Ivy League college, used the opportunity of such an address (herself standing in for a rejected speaker) to offer a timely and ringing endorsement of free speech. Her words perfectly illustrate epideictic rhetoric:

Universities have a special obligation to protect free speech, open discourse and the value of protest. The collision of views and ideologies is in the DNA of the academic enterprise. No collision avoidance technology is needed here. The noise from this discord may cause others to criticize the legitimacy of the academic enterprise, but how can knowledge advance without the questions that overturn misconceptions, push further into previously impenetrable areas of inquiry and assure us stunning breakthroughs in human knowledge? If there is anything that colleges must encourage and protect it is the persistent questioning of the status quo. Our health as a nation, our health as women, our health as an industry requires it.

— Ruth J. Simmons, Smith College, 2014

Perhaps more common than Smith’s impassioned address are values arguments that examine contemporary culture, praising what’s admirable and blaming what’s not. In the following argument, student Latisha Chisholm looks at the state of rap music after Tupac Shakur:

With the death of Tupac, not only did one of the most intriguing rap rivalries of all time die, but the motivation for rapping seems to have changed. Where money had always been a plus, now it is obviously more important than wanting to express the hardships of Black communities. With current rappers, the positive power that came from the desire to represent Black people is lost. One of the biggest rappers now got his big break while talking about sneakers. Others announce retirement without really having done much for the soul or for Black people’s morale. I equate new rappers to NFL players that don’t love the game anymore. They’re only in it for the money. . . . It looks like the voice of a people has lost its heart.

— Latisha Chisholm, “Has Rap Lost Its Soul?”

As in many ceremonial arguments, Chisholm here reinforces common values such as representing one’s community honorably and fairly.

RESPOND •

In a recent magazine, newspaper, or blog, find three editorials — one that makes a forensic argument, one a deliberative argument, and one a ceremonial argument. Analyze the arguments by asking these questions: Who is arguing? What purposes are the writers trying to achieve? To whom are they directing their arguments? Then decide whether the arguments’ purposes have been achieved and how you know.

Occasions for Argument

| Past | Future | Present | |

|---|---|---|---|

| What is it called? | Forensic | Deliberative | Epideictic |

| What are its concerns? | What happened in the past? | What should be done in the future? | Who or what deserves praise or blame? |

| What does it look like? | Court decisions, legal briefs, legislative hearings, investigative reports, academic studies | White papers, proposals, bills, regulations, mandates | Eulogies, graduation speeches, inaugural addresses, roasts |