Kinds of Argument

Kinds of Argument

Yet another way of categorizing arguments is to consider their status or stasis — that is, the specific kinds of issues they address. This approach, called stasis theory, was used in ancient Greek and Roman civilizations to provide questions designed to help citizens and lawyers work their way through legal cases. The status questions were posed in sequence because each depended on answers from the preceding ones. Together, the queries helped determine the point of contention in an argument — where the parties disagreed or what exactly had to be proven. A modern version of those questions might look like the following:

Did something happen?

What is its nature?

What is its quality or cause?

What actions should be taken?

Each stasis question explores a different aspect of a problem and uses different evidence or techniques to reach conclusions. You can use these questions to explore the aspects of any topic you’re considering. You’ll discover that we use the stasis issues to define key types of argument in Part 2.

Did Something Happen? Arguments of Fact

There’s no point in arguing a case until its basic facts are established. So an argument of fact usually involves a statement that can be proved or disproved with specific evidence or testimony. For example, the question of pollution of the oceans — is it really occurring? — might seem relatively easy to settle. Either scientific data prove that the oceans are being dirtied as a result of human activity, or they don’t. But to settle the matter, writers and readers need to ask a number of other questions about the “facts”:

Where did the facts come from?

Are they reliable?

Is there a problem with the facts?

Where did the problem begin and what caused it?

For more on arguments based on facts, see Chapters 4 and 8.

What Is the Nature of the Thing? Arguments of Definition

Some of the most hotly debated issues in American life today involve questions of definition: we argue over the nature of the human fetus, the meaning of “amnesty” for immigrants, the boundaries of sexual assault. As you might guess, issues of definition have mighty consequences, and decades of debate may nonetheless leave the matter unresolved. Here, for example, is how one type of sexual assault is defined in an important 2007 report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice by the National Institute of Justice:

We consider as incapacitated sexual assault any unwanted sexual contact occurring when a victim is unable to provide consent or stop what is happening because she is passed out, drugged, drunk, incapacitated, or asleep, regardless of whether the perpetrator was responsible for her substance use or whether substances were administered without her knowledge. We break down incapacitated sexual assault into four subtypes...

— “The Campus Sexual Assault (CSA) Study: Final Report”

The specifications of the definition go on for another two hundred words, each of consequence in determining how sexual assault on college campuses might be understood, measured, and addressed.

Of course many arguments of definition are less weighty than this, though still hotly contested: Is playing video games a sport? Can Batman be a tragic figure? Is Hillary Clinton a moderate or a progressive? (For more about arguments of definition, see Chapter 9.)

What Is the Quality or Cause of the Thing? Arguments of Evaluation

Arguments of evaluation present criteria and then measure individual people, ideas, or things against those standards. For instance, a Washington Post story examining long-term trend lines in SAT reading scores opened with this qualitative assessment of the results:

Reading scores on the SAT for the high school class of 2012 reached a four-decade low, putting a punctuation mark on a gradual decline in the ability of college-bound teens to read passages and answer questions about sentence structure, vocabulary and meaning on the college entrance exam. . . . Scores among every racial group except for those of Asian descent declined from 2006 levels. A majority of test takers — 57 percent — did not score high enough to indicate likely success in college, according to the College Board, the organization that administers the test.

— Lyndsey Layton and Emma Brown, “SAT Reading Scores Hit a Four-Decade Low”

The final sentence is particularly telling, putting the test results in context. More than half the high school test-takers may not be ready for college-level readings.

In examining a circumstance or situation like this, we are often led to wonder what accounts for it: Why are the test scores declining? Why are some groups underperforming? And, in fact, the authors of the brief Post story do follow up on some questions of cause and effect:

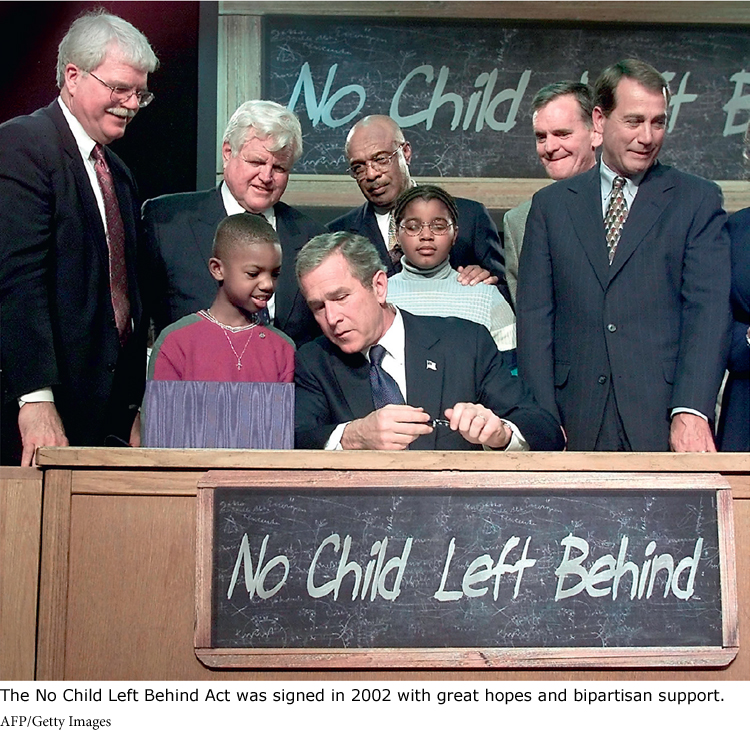

The 2012 SAT scores come after a decade of efforts to raise test scores under the No Child Left Behind law, the federal education initiative crafted by President George W. Bush. Critics say the law failed to address the barriers faced by many test takers.

“Some kids are coming to school hungry, some without the health care they need, without the vocabulary that middle-class kids come to school with, even in kindergarten,” said Helen F. Ladd, a professor of public policy and economics at Duke University.

Although evaluations differ from causal analyses, in practice the boundaries between stasis questions are often porous: particular arguments have a way of defining their own issues.

For much more about arguments of evaluation, see Chapter 10; for causal arguments, see Chapter 11.

What Actions Should Be Taken? Proposal Arguments

After facts in a controversy have been confirmed, definitions agreed on, evaluations made, and causes traced, it may be time for a proposal argument answering the question Now, what do we do about all this? For example, in developing an argument about out-of-control student fees at your college, you might use all the prior stasis questions to study the issue and determine exactly how much and for what reasons these costs are escalating. Only then will you be prepared to offer knowledgeable suggestions for action. In examining a nationwide move to eliminate remedial education in four-year colleges, John Cloud offers a notably moderate proposal to address the problem:

Students age twenty-two and over account for 43 percent of those in remedial classrooms, according to the National Center for Developmental Education… . [But] 55 percent of those needing remediation must take just one course. Is it too much to ask them to pay extra for that class or take it at a community college?

— John Cloud, “Who’s Ready for College?”

For more about proposal arguments, see Chapter 12.