Appealing to Audiences

Appealing to Audiences

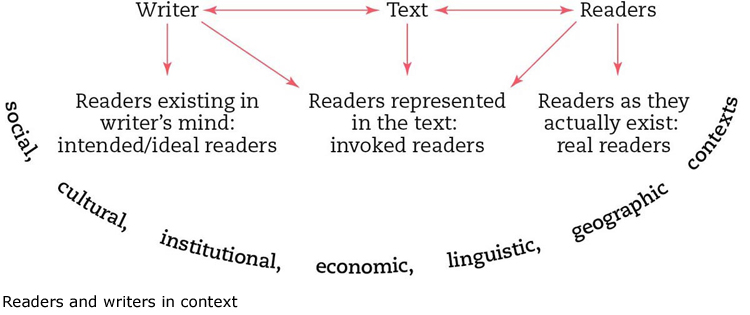

Exploring all the occasions and kinds of arguments available will lead you to think about the audience(s) you are addressing and the specific ways you can appeal to them. Audiences for arguments today are amazingly diverse, from the flesh-and-blood person sitting across a desk when you negotiate a student loan to your “friends” on social media, to the “ideal” reader you imagine for whatever you are writing. The figure below suggests just how many dimensions an audience can have as writers and readers negotiate their relationships with a text, whether it be oral, written, or digital.

As you see there, texts usually have intended readers, the people writers hope and expect to address — let’s say, routine browsers of a newspaper’s op-ed page. But writers also shape the responses of these actual readers in ways they imagine as appropriate or desirable — for example, maneuvering readers of editorials into making focused and knowledgeable judgments about politics and culture. Such audiences, as imagined and fashioned by writers within their texts, are called invoked readers.

Making matters even more complicated, readers can respond to writers’ maneuvers by choosing to join the invoked audiences, to resist them, or maybe even to ignore them. Arguments may also attract “real” readers from groups not among those that writers originally imagined or expected to reach. You may post something on the Web, for instance, and discover that people you did not intend to address are commenting on it. (For them, the experience may be like reading private email intended for someone else: they find themselves drawn to and fascinated by your ideas!) As authors of this book, we think about students like you whenever we write: you are our intended readers. But notice how in dozens of ways, from the images we choose to the tone of our language, we also invoke an audience of people who take writing arguments seriously. We want you to become that kind of reader.

So audiences are very complicated and subtle and challenging, and yet you somehow have to attract and even persuade them. As always, Aristotle offers an answer. He identified three time-tested appeals that speakers and writers can use to reach almost any audience, labeling them pathos, ethos, and logos — strategies as effective today as they were in ancient times, though we usually think of them in slightly different terms. Used in the right way and deployed at the right moment, emotional, ethical, and logical appeals have enormous power, as we’ll see in subsequent chapters.

RESPOND •

You can probably provide concise descriptions of the intended audience for most textbooks you have encountered. But can you detect their invoked audiences — that is, the way their authors are imagining (and perhaps shaping) the readers they would like to have? Carefully review this entire first chapter, looking for signals and strategies that might identify the audience and readers invoked by the authors of Everything’s an Argument.

Emotional Appeals: Pathos

Emotional appeals, or pathos, generate emotions (fear, pity, love, anger, jealousy) that the writer hopes will lead the audience to accept a claim. Here is an alarming sentence from a book by Barry B. LePatner arguing that Americans need to make hard decisions about repairing the country’s failing infrastructure:

When the I-35W Bridge in Minneapolis shuddered, buckled, and collapsed during the evening rush hour on Wednesday, August 1, 2007, plunging 111 vehicles into the Mississippi River and sending thirteen people to their deaths, the sudden, apparently inexplicable nature of the event at first gave the appearance of an act of God.

— Too Big to Fall: America’s Failing Infrastructure and the Way Forward

If you ever drive across a bridge, LePatner has probably gotten your attention. His sober and yet descriptive language helps readers imagine the dire consequence of neglected road maintenance and bad design decisions. Making an emotional appeal like this can dramatize an issue and sometimes even create a bond between writer and readers. (For more about emotional appeals, see Chapter 2.)

Ethical Appeals: Ethos

When writers or speakers come across as trustworthy, audiences are likely to listen to and accept their arguments. That trustworthiness (along with fairness and respect) is a mark of ethos, or credibility. Showing that you know what you are talking about exerts an ethical appeal, as does emphasizing that you share values with and respect your audience. Once again, here’s Barry LePatner from Too Big to Fall, shoring up his authority for writing about problems with America’s roads and bridges by invoking the ethos of people even more credible:

For those who would seek to dismiss the facts that support the thesis of this book, I ask them to consult the many professional engineers in state transportation departments who face these problems on a daily basis. These professionals understand the physics of bridge and road design, and the real problems of ignoring what happens to steel and concrete when they are exposed to the elements without a strict regimen of ongoing maintenance.

It’s a sound rhetorical move to enhance credibility this way. For more about ethical appeals, see Chapter 3.

Logical Appeals: Logos

Appeals to logic, or logos, are often given prominence and authority in U.S. culture: “Just the facts, ma’am,” a famous early TV detective on Dragnet used to say. Indeed, audiences respond well to the use of reasons and evidence — to the presentation of facts, statistics, credible testimony, cogent examples, or even a narrative or story that embodies a sound reason in support of an argument. Following almost two hundred pages of facts, statistics, case studies, and arguments about the sad state of American bridges, LePatner can offer this sober, logical, and inevitable conclusion:

We can no longer afford to ignore the fact that we are in the midst of a transportation funding crisis, which has been exacerbated by an even larger and longer-term problem: how we choose to invest in our infrastructure. It is not difficult to imagine the serious consequences that will unfold if we fail to address the deplorable conditions of our bridges and roads, including the increasingly higher costs we will pay for goods and services that rely on that transportation network, and a concomitant reduction in our standard of living.

For more about logical appeals, see Chapter 4.

Bringing It Home: Kairos and the Rhetorical Situation

In Greek mythology, Kairos — the youngest son of Zeus — was the god of opportunity. In images, he is most often depicted as running, and his most unusual characteristic is a shock of hair on his forehead. As Kairos dashes by, you have a chance to seize that lock of hair, thereby seizing the opportune moment; once he passes you by, however, you have missed that chance.

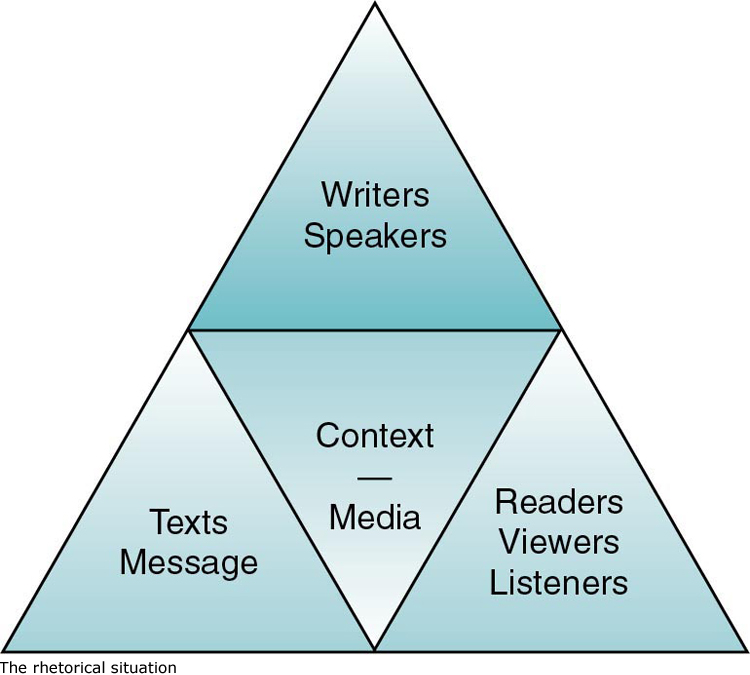

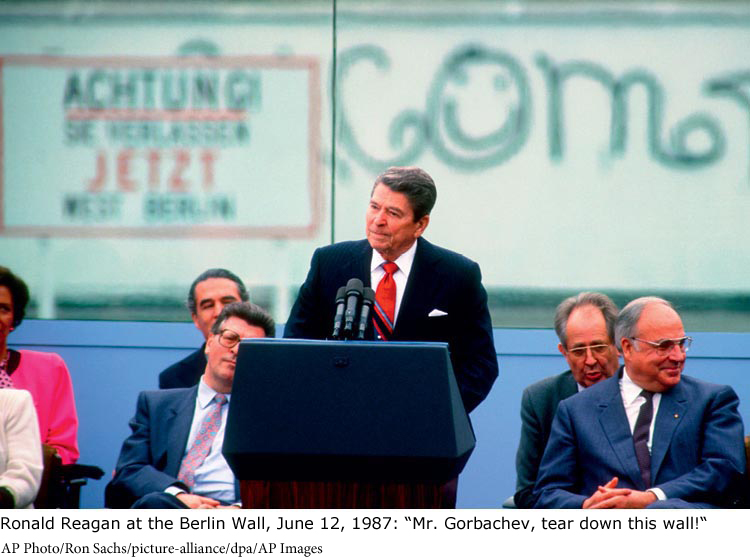

Kairos is also a term used to describe the most suitable time and place for making an argument and the most opportune ways of expressing it. It is easy to point to shimmering rhetorical moments, when speakers find exactly the right words to stir an audience: Franklin Roosevelt’s “We have nothing to fear but fear itself,” Ronald Reagan’s “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall,” and of course Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I have a dream . . .” But kairos matters just as much in less dramatic situations, whenever speakers or writers must size up the core elements of a rhetorical situation to decide how best to make their expertise and ethos work for a particular message aimed at a specific audience. The diagram above hints at the dynamic complexity of the rhetorical situation.

But rhetorical situations are embedded in contexts of enormous social complexity. The moment you find a subject, you inherit all the knowledge, history, culture, and technological significations that surround it. To lesser and greater degrees (depending on the subject), you also bring personal circumstances into the field — perhaps your gender, your race, your religion, your economic class, your habits of language. And all those issues weigh also upon the people you write to and for.

So considering your rhetorical situation calls on you to think hard about the notion of kairos. Being aware of your rhetorical moment means being able to understand and take advantage of dynamic, shifting circumstances and to choose the best (most timely) proofs and evidence for a particular place, situation, and audience. It means seizing moments and enjoying opportunities, not being overwhelmed by them. Doing so might even lead you to challenge the title of this text: is everything an argument?

That’s what makes writing arguments exciting.

RESPOND •

Take a look at the bumper sticker below, and then analyze it. What is its purpose? What kind of argument is it? Which of the stasis questions does it most appropriately respond to? To what audiences does it appeal? What appeals does it make and how?