Using Emotions to Build Bridges

Using Emotions to Build Bridges

You may sometimes want to use emotions to connect with readers to assure them that you understand their experiences or “feel their pain,” to borrow a sentiment popularized by President Bill Clinton. Such a bridge is especially important when you’re writing about matters that readers regard as sensitive. Before they’ll trust you, they’ll want assurances that you understand the issues in depth. If you strike the right emotional note, you’ll establish an important connection. That’s what Apple founder Steve Jobs does in a much-admired 2005 commencement address in which he tells the audience that he doesn’t have a fancy speech, just three stories from his life:

My second story is about love and loss. I was lucky. I found what I loved to do early in life. Woz [Steve Wozniak] and I started Apple in my parents’ garage when I was twenty. We worked hard and in ten years, Apple had grown from just the two of us in a garage into a $2 billion company with over four thousand employees. We’d just released our finest creation, the Macintosh, a year earlier, and I’d just turned thirty, and then I got fired. How can you get fired from a company you started? Well, as Apple grew, we hired someone who I thought was very talented to run the company with me, and for the first year or so, things went well. But then our visions of the future began to diverge, and eventually we had a falling out. When we did, our board of directors sided with him, and so at thirty, I was out, and very publicly out. . . .

I didn’t see it then, but it turned out that getting fired from Apple was the best thing that could have ever happened to me. The heaviness of being successful was replaced by the lightness of being a beginner again, less sure about everything. It freed me to enter one of the most creative periods in my life. During the next five years I started a company named NeXT, another company named Pixar and fell in love with an amazing woman who would become my wife. Pixar went on to create the world’s first computer-animated feature film, Toy Story, and is now the most successful animation studio in the world.

— Steve Jobs, “You’ve Got to Find What You Love, Jobs Says”

In no obvious way is Jobs’s recollection a formal argument. But it prepares his audience to accept the advice he’ll give later in his speech, at least partly because he’s speaking from meaningful personal experiences.

A more obvious way to build an emotional tie is simply to help readers identify with your experiences. If, like Georgina Kleege, you were blind and wanted to argue for more sensible attitudes toward blind people, you might ask readers in the first paragraph of your argument to confront their prejudices. Here Kleege, a writer and college instructor, makes an emotional point by telling a story:

The excerpt from Shabana Mir’s book Muslim American Women on Campus opens with comments that unify the undergraduate experience.

I tell the class, “I am legally blind.” There is a pause, a collective intake of breath. I feel them look away uncertainly and then look back. After all, I just said I couldn’t see. Or did I? I had managed to get there on my own — no cane, no dog, none of the usual trappings of blindness. Eyeing me askance now, they might detect that my gaze is not quite focused. . . . They watch me glance down, or towards the door where someone’s coming in late. I’m just like anyone else.

— Georgina Kleege, “Call It Blindness”

Given the way she narrates the first day of class, readers are as likely to identify with the students as with Kleege, imagining themselves sitting in a classroom, facing a sightless instructor, confronting their own prejudices about the blind. Kleege wants to put her audience on the edge emotionally.

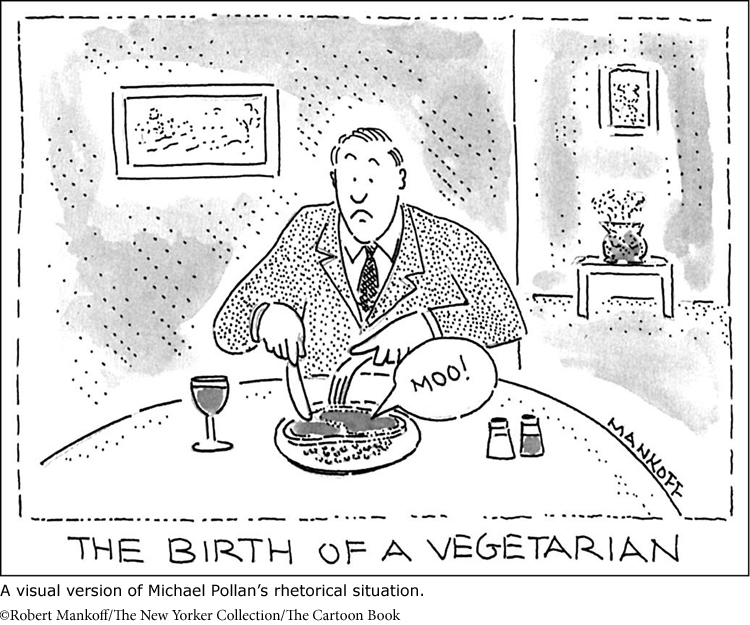

Let’s consider another rhetorical situation: how do you win over an audience when the logical claims that you’re making are likely to go against what many in the audience believe? Once again, a slightly risky appeal to emotions on a personal level may work. That’s the tack that Michael Pollan takes in bringing readers to consider that “the great moral struggle of our time will be for the rights of animals.” In introducing his lengthy exploratory argument, Pollan uses personal experience to appeal to his audience:

The first time I opened Peter Singer’s Animal Liberation, I was dining alone at the Palm, trying to enjoy a rib-eye steak cooked medium-rare. If this sounds like a good recipe for cognitive dissonance (if not indigestion), that was sort of the idea. Preposterous as it might seem to supporters of animal rights, what I was doing was tantamount to reading Uncle Tom’s Cabin on a plantation in the Deep South in 1852.

— Michael Pollan, “An Animal’s Place”

In creating a vivid image of his first encounter with Singer’s book, Pollan’s opening builds a bridge between himself as a person trying to enter into the animal rights debate in a fair and open-minded, if still skeptical, way and readers who might be passionate about either side of this argument.