4.1 Arguments Based on Facts and Reason: Logos

4

Arguments Based on Facts and Reason: Logos

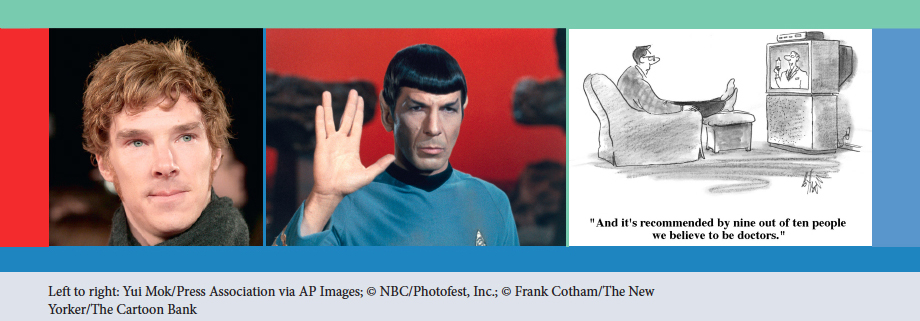

These three images say a lot about the use and place of logic (logos) in Western and American culture. The first shows Benedict Cumberbatch from the BBC TV series Sherlock, just one of many actors to play Arthur Conan Doyle’s much-loved fictional detective Sherlock Holmes, who solves perplexing crimes by using precise observation and impeccable logic. The second refers to an equally popular TV (and film) series character, Spock, the Vulcan officer in Star Trek who tries to live a life guided by reason alone — his most predicable observation being some version of “that would not be logical.” The third is a cartoon spoofing a pseudo-logical argument (nine out of ten prefer X) made so often in advertising that it has become something of a joke.

These images attest to the prominent place that logic holds for most people: like Holmes, we want to know the facts on the assumption that they will help us make sound judgments. We admire those whose logic is, like Spock’s, impeccable. So when arguments begin, “Nine out of ten authorities recommend,” we respond favorably: those are good odds. But the three images also challenge reliance on logic alone: Sherlock Holmes and Spock are characters drawn in broad and often parodic strokes; the “nine out of ten” cartoon itself spoofs abuses of reason. Given a choice, however, most of us profess to respect and even prefer appeals to logos — that is, claims based on facts, evidence, and reason — but we’re also inclined to read factual arguments within the context of our feelings and the ethos of people making the appeals.