Using Reason and Common Sense

Using Reason and Common Sense

If you don’t have “hard facts,” you can turn to those arguments Aristotle describes as “constructed” from reason and common sense. The formal study of such reasoning is called logic, and you probably recognize a famous example of deductive reasoning, called a syllogism:

All human beings are mortal.

Socrates is a human being.

Therefore, Socrates is mortal.

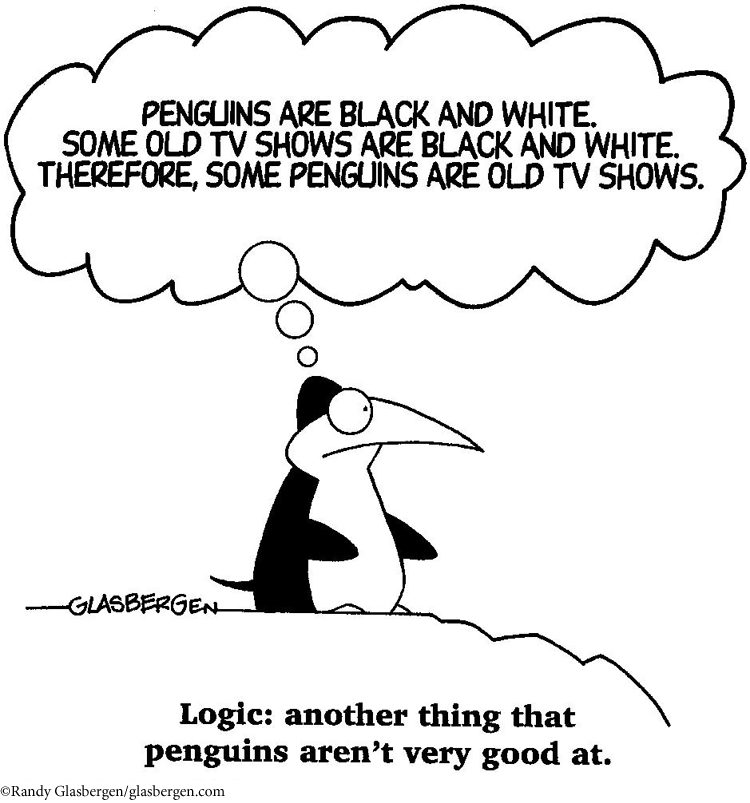

In valid syllogisms, the conclusion follows logically — and technically — from the premises that lead up to it. Many have criticized syllogistic reasoning for being limited, and others have poked fun at it, as in the cartoon below.

But we routinely see something like syllogistic reasoning operating in public arguments, particularly when writers take the time to explain key principles. Consider the step-by-step reasoning Michael Gerson uses to explain why exactly it was wrong for the Internal Revenue Service in 2010–2011 to target specific political groups, making it more difficult for them to organize politically:

Why does this matter deserve heightened scrutiny from the rest of us? Because crimes against democracy are particularly insidious. Representative government involves a type of trade. As citizens, we cede power to public officials for important purposes that require centralized power: defending the country, imposing order, collecting taxes to promote the common good. In exchange, we expect public institutions to be evenhanded and disinterested. When the stewards of power — biased judges or corrupt policemen or politically motivated IRS officials — act unfairly, it undermines trust in the whole system.

— Michael Gerson, “An Arrogant and Lawless IRS”

Gerson’s criticism of the IRS actions might be mapped out by the following sequence of statements.

Crimes against democracy undermine trust in the system.

Treating taxpayers differently because of their political beliefs is a crime against democracy.

Therefore, IRS actions that target political groups undermine the American system.

Few writers, of course, think about formal deductive reasoning when they support their claims. Even Aristotle recognized that most people argue perfectly well using informal logic. To do so, they rely mostly on habits of mind and assumptions that they share with their readers or listeners — as Gerson essentially does in his paragraph.

In Chapter 7, we describe a system of informal logic that you may find useful in shaping credible appeals to reason — Toulmin argument. Here, we briefly examine some ways that people use informal logic in their everyday lives. Once again, we begin with Aristotle, who used the term enthymeme to describe an ordinary kind of sentence that includes both a claim and a reason but depends on the audience’s agreement with an assumption that is left implicit rather than spelled out. Enthymemes can be very persuasive when most people agree with the assumptions they rest on. The following sentences are all enthymemes:

We’d better cancel the picnic because it’s going to rain.

Flat taxes are fair because they treat everyone the same.

I’ll buy a PC instead of a Mac because it’s cheaper.

Sometimes enthymemes seem so obvious that readers don’t realize that they’re drawing inferences when they agree with them. Consider the first example:

We’d better cancel the picnic because it’s going to rain.

Let’s expand the enthymeme a bit to say more of what the speaker may mean:

We’d better cancel the picnic this afternoon because the weather bureau is predicting a 70 percent chance of rain for the remainder of the day.

Embedded in this brief argument are all sorts of assumptions and fragments of cultural information that are left implicit but that help to make it persuasive:

Picnics are ordinarily held outdoors.

When the weather is bad, it’s best to cancel picnics.

Rain is bad weather for picnics.

A 70 percent chance of rain means that rain is more likely to occur than not.

When rain is more likely to occur than not, it makes sense to cancel picnics.

For most people, the original statement carries all this information on its own; the enthymeme is a compressed argument, based on what audiences know and will accept.

But sometimes enthymemes aren’t self-evident:

Be wary of environmentalism because it’s religion disguised as science.

iPhones are undermining civil society by making us even more focused on ourselves.

It’s time to make all public toilets unisex because to do otherwise is discriminatory.

In these cases, you’ll have to work much harder to defend both the claim and the implicit assumptions that it’s based on by drawing out the inferences that seem self-evident in other enthymemes. And you’ll likely also have to supply credible evidence; a simple declaration of fact won’t suffice.