Rhetorical Analysis:

6

Rhetorical Analysis

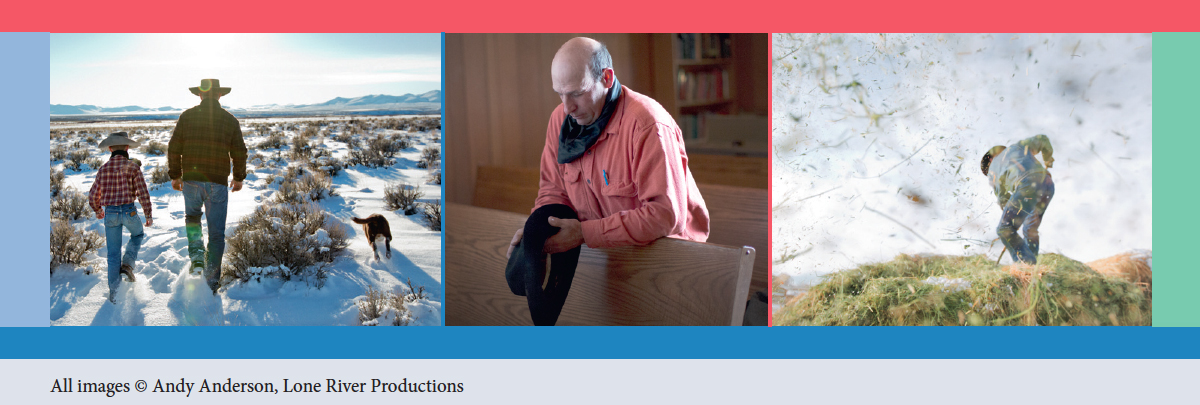

If you watched the 2013 Super Bowl between the Baltimore Ravens and the San Francisco 49ers, you may remember the commercial. For two solemn minutes, still photographs of rural America and the people who work there moved across the screen accompanied by the unmistakable voice of the late Paul Harvey reading words he had first delivered in 1978. Maria Godoy of NPR described it this way: “It may not have been as dramatic as the stadium blackout that halted play for more than a half-hour, or as extravagant as Beyonce’s halftime show. But for many viewers of Super Bowl XLVII, one of the standout moments was a deceptively simple ad for the Dodge Ram called ‘God Made a Farmer.’” It was a fourth quarter interrupted by cattle, churches, snowy farmyards, bales of hay, plowed fields, hardworking men, and a few sturdy women. Occasionally, a slide discreetly showed a Ram truck, sponsor of the video, but there were no overt sales pitches — only a product logo in the final frame. Yet visits to the Ram Web site spiked immediately, and sales of Ram pickups did too. (The official video has been viewed on YouTube more than 17 million times.)

So how to account for the appeal of such an unconventional and unexpected commercial? That would be the work of a rhetorical analysis, the close reading of a text or, in this case, a video commercial, to figure out exactly how it functions. Certainly, the creators of “God Made a Farmer” counted on the strong emotional appeal of the photographs they’d commissioned, guessing perhaps that the expert images and Harvey’s spellbinding words would contrast powerfully with the frivolity and emptiness of much Super Bowl ad fare:

God said, “I need somebody willing to sit up all night with a newborn colt. And watch it die. Then dry his eyes and say, ‘Maybe next year.’”

They pushed convention, too, by the length of the spot and the muted product connection, doubtless hoping to win the goodwill of a huge audience suddenly all teary-eyed in the midst of a football game. And they surely gained the respect of a great many truck-buying farmers.

Rhetorical analyses can also probe the contexts that surround any argument or text — its impact on a society, its deeper implications, or even what it lacks or whom it excludes. Predictably, the widely admired Ram commercial (selected #1 Super Bowl XLVII spot by Adweek) acquired its share of critics, some attacking it for romanticizing farm life, others for ignoring the realities of industrial agriculture. And not a few writers noted what they regarded as glaring absences in its representation of farmers. Here, for instance, is copywriter and blogger Edye Deloch-Hughes, offering a highly personal and conflicted view of the spot in what amounts to an informal rhetorical analysis:

. . . I was riveted by the still photography and stirring thirty-five-year-old delivery of legendary radio broadcaster Paul Harvey. But as I sat mesmerized, I waited to see an image that spoke to my heritage. What flashed before me were close-ups of stoic white men whose faces drowned out the obligatory medium shots of a minority token or two; their images minimized against the amber waves of grain.

God made a Black farmer too. Where was my Grandpa, Grandma and Great Granny? My Auntie and Uncle Bolden? And didn’t God make Hispanic and Native American farmers? They too were under-represented.

I am the offspring of a century and a half of African-American caretakers of the land, from Arkansas, Mississippi and Louisiana, who experienced their toils and troubles, their sun ups and sun downs. Their injustices and beat-downs. I wrestled with my mixed emotions; loving the commercial and feeling dejected at the same time.

. . . Minimizing positive Black imagery and accomplishments is as American as wrestling cattle. We’re often footnotes or accessories in history books, TV shows, movies and magazines as well as TV commercials. When content is exceptional, the omission is harder to recognize or criticize. Some friends of mine saw — or rather felt — the omission as I did. Others did not. I say be aware and vocal about how you are represented — if represented at all, otherwise your importance and relevance will be lost.

— Edye Deloch-Hughes, “So God Made a Black Farmer Too”

As this example suggests, whenever you undertake a rhetorical analysis, follow your instincts and look closely. Why does an ad for a cell phone or breakfast sandwich make people want one immediately? How does an op-ed piece in the Washington Post suddenly change your long-held position on immigration? A rhetorical analysis might help you understand. Dig as deep as you can into the context of the item you are analyzing, especially when you encounter puzzling, troubling, or unusually successful appeals — ethical, emotional, or logical. Ask yourself what strategies a speech, editorial, opinion column, film, or ad spot employs to move your heart, win your trust, and change your mind — or why, maybe, it fails to do so.