Looking at Style

Looking at Style

Even a coherent argument full of sound evidence may not connect with readers if it’s dull, off-key, or offensive. Readers naturally judge the credibility of arguments in part by how stylishly the case is made — even when they don’t know exactly what style is (for more on style, see Chapter 13). Consider how these simple, blunt sentences from the opening of an argument shape your image of the author and probably determine whether you’re willing to continue to read the whole piece:

We are young, urban, and professional. We are literate, respectable, intelligent, and charming. But foremost and above all, we are unemployed.

— Julia Carlisle, “Young, Privileged, and Unemployed”

The strong, straightforward tone and the stark juxtaposition of being “intelligent” with “unemployed” set the style for this letter to the editor.

Now consider the brutally sarcastic tone of Nathaniel Stein’s hilarious parody of the Harvard grading policy, a piece he wrote following up on a professor’s complaint of out-of-control grade inflation at the school. Stein borrows the formal language of a typical “grading standards” sheet to mock the decline in rigor that the professor has lamented:

The A+ grade is used only in very rare instances for the recognition of truly exceptional achievement.

For example: A term paper receiving the A+ is virtually indistinguishable from the work of a professional, both in its choice of paper stock and its font. The student’s command of the topic is expert, or at the very least intermediate, or beginner. Nearly every single word in the paper is spelled correctly; those that are not can be reasoned out phonetically within minutes. Content from Wikipedia is integrated with precision. The paper contains few, if any, death threats. . . .

An overall course grade of A+ is reserved for those students who have not only demonstrated outstanding achievement in coursework but have also asked very nicely.

Finally, the A+ grade is awarded to all collages, dioramas and other art projects.

— Nathaniel Stein, “Leaked! Harvard’s Grading Rubric”

Both styles probably work, but they signal that the writers are about to make very different kinds of cases. Here, style alone tells readers what to expect.

Manipulating style also enables writers to shape readers’ responses to their ideas. Devices as simple as repetition, parallelism, or even paragraph length can give sentences remarkable power. Consider this passage from an essay by Sherman Alexie in which he explores the complex reaction of straight men to the announcement of NBA star Jason Collins that he is gay:

Homophobic basketball fans will disparage his skills, somehow equating his NBA benchwarmer status with his sexuality. But let’s not forget that Collins is still one of the best 1,000 basketball players in the world. He has always been better than his modest statistics would indicate, and his teams have been dramatically more efficient with him on the court. He is better at hoops than 99.9 percent of you are at anything you do. He might not be a demigod, but he’s certainly a semi-demigod. Moreover, his basketball colleagues universally praise him as a physically and mentally tough player. In his prime, he ably battled that behemoth known as Shaquille O’Neal. Most of all, Collins is widely regarded as one of the finest gentlemen to ever play the game. Generous, wise, and supportive, he’s a natural leader. And he has a degree from Stanford University.

In other words, he’s a highly attractive dude.

— Sherman Alexie, “Jason Collins Is the Envy of Straight Men Everywhere”

In this passage, Alexie uses a sequence of short, direct, and roughly parallel sentences (“He is . . . He might . . . He ably battled . . . He has”) to present evidence justifying the playful point he makes in a pointedly emphatic, one-sentence paragraph. The remainder of his short essay then amplifies that point.

In a rhetorical analysis, you can explore such stylistic choices. Why does a formal style work for discussing one type of subject matter but not another? How does a writer use humor or irony to underscore an important point or to manage a difficult concession? Do stylistic choices, even something as simple as the use of contractions or personal pronouns, bring readers close to a writer, or do technical words and an impersonal voice signal that an argument is for experts only?

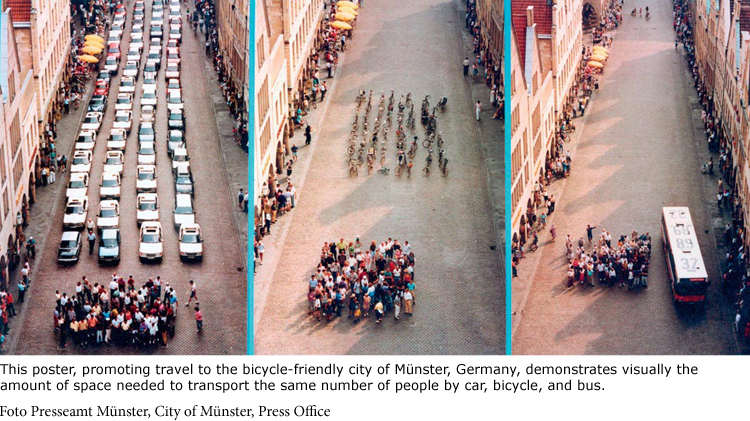

To describe the stylistic effects of visual arguments, you may use a different vocabulary and talk about colors, camera angles, editing, balance, proportion, fonts, perspective, and so on. But the basic principle is this: the look of an item — whether a poster, an editorial cartoon, or a film documentary — can support the message that it carries, undermine it, or muddle it. In some cases, the look will be the message. In a rhetorical analysis, you can’t ignore style.

RESPOND •

Find a recent example of a visual argument, either in print or on the Internet. Even though you may have a copy of the image, describe it carefully in your paper on the assumption that your description is all readers may have to go on. Then make a judgment about its effectiveness, supporting your claim with clear evidence from the “text.”