The Classical Oration

The Classical Oration

The authors of this book once examined a series of engineering reports and found that — to their great surprise — these reports were generally structured in ways similar to those used by Greek and Roman rhetors two thousand years ago. Thus, this ancient structuring system is alive and well in twenty-first-century culture. The classical oration has six parts, most of which will be familiar to you, despite their Latin names:

Exordium: You try to win the attention and goodwill of an audience while introducing a topic or problem.

danah boyd and Kate Crawford provide a narratio that establishes a context for their argument when they examine the motivations behind Big Data in Six Provocations for Big Data.

Narratio: You present the facts of the case, explaining what happened when, who is involved, and so on. The narratio puts an argument in context.

Partitio: You divide up the topic, explaining what the claim is, what the key issues are, and in what order they will be treated.

Confirmatio: You offer detailed support for the claim, using both logical reasoning and factual evidence.

Refutatio: You carefully consider and respond to opposing claims or evidence.

Peroratio: You summarize the case and move the audience to action.

This structure is powerful because it covers all the bases: readers or listeners want to know what your topic is, how you intend to cover it, and what evidence you have to offer. And you probably need a reminder to present a pleasing ethos when beginning a presentation and to conclude with enough pathos to win an audience over completely. Here, in outline form, is a five-part updated version of the classical pattern, which you may find useful on many occasions:

Introduction

gains readers’ interest and willingness to listen

establishes your qualifications to write about your topic

establishes some common ground with your audience

demonstrates that you’re fair and even-handed

states your claim

Background

presents information, including personal stories or anecdotes that are important to your argument

Lines of Argument

presents good reasons, including logical and emotional appeals, in support of your claim

Alternative Arguments

carefully considers alternative points of view and opposing arguments

notes the advantages and disadvantages of these views

explains why your view is preferable to others

Conclusion

summarizes the argument

elaborates on the implications of your claim

makes clear what you want the audience to think or do

reinforces your credibility and perhaps offers an emotional appeal

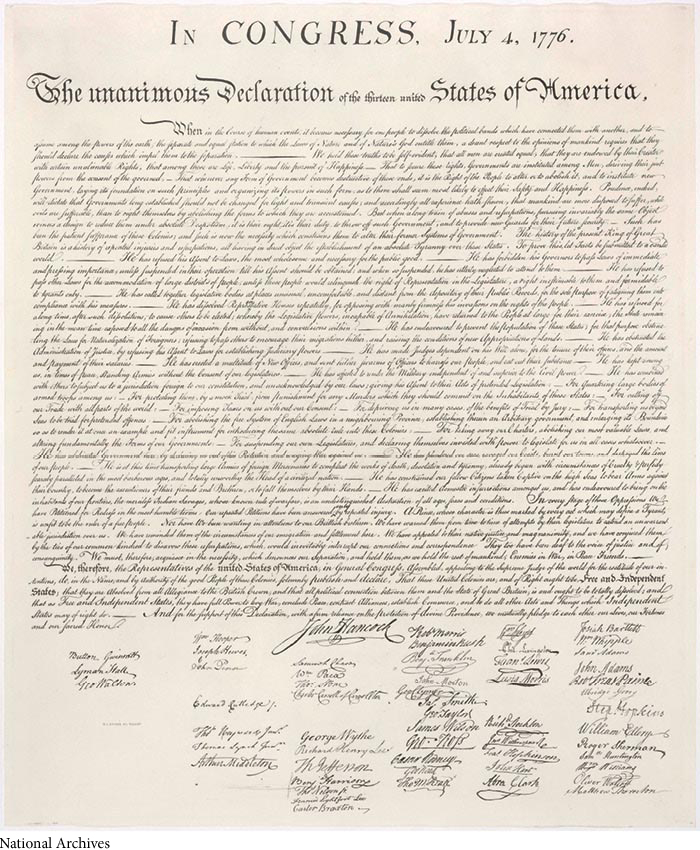

Not every piece of rhetoric, past or present, follows the structure of the oration or includes all its components. But you can identify some of its elements in successful arguments if you pay attention to their design. Here are the words of the 1776 Declaration of Independence:

— Opens with a brief exordium explaining why the document is necessary, invoking a broad audience in acknowledging a need to show “a decent respect to the opinions of mankind.” Important in this case, the lines that follow explain the assumptions on which the document rests.

When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness — that to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed — That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive to these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it and to institute new Government, laying its Foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government and to provide new Guards for their future security. — Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world.

— A narratio follows, offering background on the situation: because the government of George III has become destructive, the framers of the Declaration are obligated to abolish their allegiance to him.

— Arguably, the partitio begins here, followed by the longest part of the document (not reprinted here), a confirmatio that lists the “long train of abuses and usurpations” by George III.

— Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1776

The authors might have structured this argument by beginning with the last two sentences of the excerpt and then listing the facts intended to prove the king’s abuse and tyranny. But by choosing first to explain the purpose and “self-evident” assumptions behind their argument and only then moving on to demonstrate how these “truths” have been denied by the British, the authors forge an immediate connection with readers and build up to the memorable conclusion. The structure is both familiar and inventive — as your own use of key elements of the oration should be in the arguments you compose.