Developing a Factual Argument

Developing a Factual Argument

Entire Web sites are dedicated to finding and posting errors from news and political sources. Some, like Media Matters for America and Accuracy in Media, take overtly partisan stands. Here’s a one-day sampling of headlines from Media Matters:

Hillary Clinton Overcompensates on Foreign Policy Because She’s a Woman

Fox Host Defends Calling Michelle Obama Fat

Fox News Decries Granting Undocumented Children Their Right to Public Education

And here’s a listing from Accuracy in Media:

An Inside Look at How Democrats Rig the Election Game

Why Obamacare Is Unfixable

The American Left: Friends to Our Country’s Enemies

It would be hard to miss the blatant political agendas at work on these sites.

Other fact-checking organizations have better reputations when it comes to assessing the truths behind political claims and media presentations. Though both are also routinely charged with bias, Pulitzer Prize–winning PolitiFact.com and FactCheck.org at least make an effort to be fair-minded across a broader political spectrum. FactCheck, for example, provides a detailed analysis of the claims it investigates in relatively neutral and denotative language, and lists the sources its researchers used — just as if its writers were doing a research paper. At its best, FactCheck.org demonstrates what one valuable kind of factual argument can accomplish.

Any factual argument that you might compose — from how you state your claim to how you present evidence and the language you use — should be similarly shaped by the occasion for the argument and a desire to serve the audiences that you hope to reach. We can offer some general advice to help you get started.

RESPOND •

The Annenberg Public Policy Center at the University of Pennsylvania hosts FactCheck.org, a Web site dedicated to separating facts from opinion or falsehood in the area of politics. It claims to be politically neutral. Find a case that interests you, either a recent controversial item listed on its homepage or another from its archives. Carefully study the item. Pay attention to the devices that FactCheck uses to suggest or ensure objectivity and the way that it handles facts and statistics. Then offer your own brief factual argument about the site’s objectivity.

Identifying an Issue

To offer a factual argument of your own, you need to identify an issue or problem that will interest you and potential readers. Look for situations or phenomena — local or national — that seem out of the ordinary in the expected order of things. For instance, you might notice that many people you know are deciding not to attend college. How widespread is this change, and who are the people making this choice?

In their report “Student Veterans/Service Members’ Engagement in College and University Life and Education,” Young M. Kim and James S. Cole offer an argument of fact when they present data from the National Survey of Student Engagement.

Or follow up claims that strike you as at odds with the facts as you know them or believe them. Maybe you doubt explanations being offered for your favorite sport team’s current slump or for the declining number of minority men in your college courses. Or you might give a local spin to factual questions that other people have already formulated on a national level. Do people in your town seem to be flocking to high-MPG vehicles or resisting bans on texting while driving or smoking in public places outdoors? You will likely write a better paper if you take on a factual question that genuinely interests you.

In fact, whole books are written when authors decide to pursue factual questions that intrigue them. But you want to be careful not to argue matters that pose no challenge for you or your audiences. You’re not offering anything new if you just try to persuade readers that smoking is harmful to their well-being. So how about something fresh in the area of health?

Quick preliminary research and reading might allow you to move from an intuition to a hypothesis, that is, a tentative statement of your claim: Having a dog is good for your health. As noted earlier, factual arguments often provoke other types of analysis. In developing this claim, you’d need to explain what “good for your health” means, potentially an argument of definition. You’d also likely find yourself researching causes of the phenomenon if you can demonstrate that it is factual. As it turns out, your canine hypothesis would have merit if you defined “good for health” as “encouraging exercise.” Here’s the lead to a New York Times story reporting recent research:

If you’re looking for the latest in home exercise equipment, you may want to consider something with four legs and a wagging tail.

Several studies now show that dogs can be powerful motivators to get people moving. Not only are dog owners more likely to take regular walks, but new research shows that dog walkers are more active overall than people who don’t have dogs.

One study even found that older people are more likely to take regular walks if the walking companion is canine rather than human.

— Tara Parker-Pope, “Forget the Treadmill. Get a Dog,” March 14, 2011

As always, there’s another side to the story: what if people likely to get dogs are the very sort already inclined to be more physically active? You could explore that possibility as well (and researchers have) and then either modify your initial hypothesis or offer a new one. That’s what hypotheses are for. They are works in progress.

RESPOND •

Working with a group of colleagues, generate a list of twenty favorite “mysteries” explored on TV shows, in blogs, or in tabloid newspapers. Here are three to get you started — the alien crash landing at Roswell, the existence of Atlantis, and the uses of Area 51. Then decide which — if any — of these puzzlers might be resolved or explained in a reasonable factual argument and which ones remain eternally mysterious and improbable. Why are people attracted to such topics? Would any of these items provide material for a noteworthy factual argument?

Researching Your Hypothesis

How and where you research your subject will depend, naturally, on your subject. You’ll certainly want to review Chapter 18, “Finding Evidence,” Chapter 19, “Evaluating Sources,” and Chapter 20, “Using Sources,” before constructing an argument of fact. Libraries and the Web will provide you with deep resources on almost every subject. Your task will typically be to separate the best sources from all the rest. The word best here has many connotations: some reputable sources may be too technical for your audiences; some accessible sources may be pitched too low or be too far removed from the actual facts.

Read the chapter from Scott L. Montgomery’s book Does Science Need a Global Language? English and the Future of Research. What kinds of research does Montgomery use? Does the fact that much of the research is apparent only in his footnotes impact his argument?

You’ll be making judgment calls like this routinely. But do use primary sources whenever you can. For example, when gathering a comment from a source on the Web, trace it whenever possible to its original site, and read the comment in its full context. When statistics are quoted, follow them back to the source that offered them first to be sure that they’re recent and reputable. Instructors and librarians can help you appreciate the differences. Understand that even sources with pronounced biases can furnish useful information, provided that you know how to use them, take their limitations into account, and then share what you know about the sources with your readers.

Sometimes, you’ll be able to do primary research on your own, especially when your subject is local and you have the resources to do it. Consider conducting a competent survey of campus opinions and attitudes, for example, or study budget documents (often public) to determine trends in faculty salaries, tuition, student fees, and so on. Primary research of this sort can be challenging because even the simplest surveys or polls have to be intelligently designed and executed in a way that samples a representative population (see Chapter 4). But the work could pay off in an argument that brings new information to readers.

Refining Your Claim

As you learn more about your subject, you might revise your hypothesis to reflect what you’ve discovered. In most cases, these revised hypotheses will grow increasingly complex and specific. Following are three versions of essentially the same claim, with each version offering more information to help readers judge its merit:

Americans really did land on the moon, despite what some people think!

Since 1969, when the Eagle supposedly landed on the moon, some people have been unjustifiably skeptical about the success of the United States’ Apollo program.

Despite plentiful hard evidence to the contrary — from Saturn V launches witnessed by thousands to actual moon rocks tested by independent labs worldwide — some people persist in believing falsely that NASA’s moon landings were actually filmed on deserts in the American Southwest as part of a massive propaganda fraud.

The additional details about the subject might also suggest new ways to develop and support it. For example, conspiracy theorists claim that the absence of visible stars in photographs of the moon landing is evidence that it was staged, but photographers know that the camera exposure needed to capture the foreground — astronauts in their bright space suits — would have made the stars in the background too dim to see. That’s a key bit of evidence for this argument.

As you advance in your research, your thesis will likely pick up even more qualifying words and expressions, which help you to make reasonable claims. Qualifiers — words and phrases such as some, most, few, for most people, for a few users, under specific conditions, usually, occasionally, seldom, and so on — will be among your most valuable tools in a factual argument. (See “Using Qualifiers” in Chapter 7, “Structuring Arguments” for more on qualifiers.)

Sometimes it is important to set your factual claim into a context that helps explain it to others who may find it hard to accept. You might have to concede some ground initially in order to see the broader picture. For instance, professor of English Vincent Carretta anticipated strong objections after he uncovered evidence that Olaudah Equiano — the author of The Interesting Narrative (1789), a much-cited autobiographical account of his Middle Passage voyage and subsequent life as a slave — may actually have been born in South Carolina and not in western Africa. Speaking to the Chronicle of Higher Education about why Equiano may have fabricated his African origins to serve a larger cause, Carretta explains:

“Whether [Equiano] invented his African birth or not, he knew that what that movement needed was a first-person account. And because they were going after the slave trade, it had to be an account of someone who had been born in Africa and was brought across the Middle Passage. An African American voice wouldn’t have done it.”

— Jennifer Howard, “Unraveling the Narrative”

Carretta asks readers to appreciate that the new facts that he has discovered about The Interesting Narrative do not undermine the work’s historical significance. If anything, his research has added new dimensions to its meaning and interpretation.

Deciding Which Evidence to Use

In this chapter, we’ve blurred the distinction between factual arguments for scientific and technical audiences and those for the general public (in magazines, blogs, social media sites, television documentaries, and so on). In the former kind of arguments, readers will expect specific types of evidence arranged in a formulaic way. Such reports may include a hypothesis, a review of existing research on the subject, a description of methods, a presentation of results, and finally a formal discussion of the findings. If you are thinking “lab report,” you are already familiar with an academic form of a factual argument with precise standards for evidence.

Less scientific factual arguments — claims about our society, institutions, behaviors, habits, and so on — are seldom so systematic, and they may draw on evidence from a great many different media. For instance, you might need to review old newspapers, scan videos, study statistics on government Web sites, read transcripts of congressional hearings, record the words of eyewitnesses to an event, glean information by following experts on Twitter, and so on. Very often, you will assemble your arguments from material found in credible, though not always concurring, authorities and resources — drawing upon the factual findings of scientists and scholars, but perhaps using their original insights in novel ways.

For example, you might be intrigued by a comprehensive report from the Kaiser Family Foundation (2010) providing the results of a study of more than 2,000 eight- to eighteen-year-old American children:

The study found that the average time spent reading books for pleasure in a typical day rose from 21 minutes in 1999 to 23 minutes in 2004, and finally to 25 minutes in 2010. The rise of screen-based media has not melted children’s brains, despite ardent warnings otherwise: “It does not appear that time spent using screen media (TV, video games and computers) displaces time spent with print media,” the report stated. Teens are not only reading more books, they’re involved in communities of like-minded book lovers.

— Hannah Withers and Lauren Ross, “Young People Are Reading More Than You”

Reading about these results, however, may raise some new questions for you: Is twenty-five minutes of reading a day really something to be happy about? What is the quality of what these young people are reading? Such questions might lead you to do a new study that could challenge the conclusion of the earlier research by bringing fresh facts to the table.

Often, you may have only a limited number of words or pages in which to make a factual argument. What do you do then? You present your best evidence as powerfully as possible. But that’s not difficult. You can make a persuasive factual case with just a few examples: three or four often suffice to make a point. Indeed, going on too long or presenting even good data in ways that make it seem uninteresting or pointless can undermine a claim.

Presenting Your Evidence

In Hard Times (1854), British author Charles Dickens poked fun at a pedagogue he named Thomas Gradgrind, who preferred hard facts before all things human or humane. When poor Sissy Jupe (called “girl number twenty” in his awful classroom) is unable at his command to define horse, Gradgrind turns to his star pupil:

“Bitzer,” said Thomas Gradgrind. “Your definition of a horse.”

“Quadruped. Graminivorous. Forty teeth, namely twenty-four grinders, four eyeteeth, and twelve incisive. Sheds coat in the spring; in marshy countries, sheds hoofs, too. Hoofs hard, but requiring to be shod with iron. Age known by marks in mouth.” Thus (and much more) Bitzer.

“Now girl number twenty,” said Mr. Gradgrind. “You know what a horse is.”

— Charles Dickens, Hard Times

But does Bitzer? Rattling off facts about a subject isn’t quite the same thing as knowing it, especially when your goal is, as it is in an argument of fact, to educate and persuade audiences. So you must take care how you present your evidence.

Factual arguments, like any others, take many forms. They can be as simple and pithy as a letter to the editor (or Bitzer’s definition of a horse) or as comprehensive and formal as a senior thesis or even a dissertation. Such a thesis might have just two or three readers mainly interested in the facts you are presenting and the competence of your work. So your presentation can be lean and relatively simple.

But to earn the attention of readers in some more public forum, you may need to work harder to be persuasive. For instance, Pew Research Center’s May 2014 formal report, Young Adults, Student Debt, and Economic Well-Being, which spends time introducing its authors and establishing their expertise, is twenty-three pages long, cites a dozen sources, and contains sixteen figures and tables. Like many such studies, it also includes a foreword, an overview, and a detailed table of contents. All these elements help readers find the facts they need while also establishing the ethos of the work, making it seem serious, credible, well conceived, and worth reading.

Considering Design and Visuals

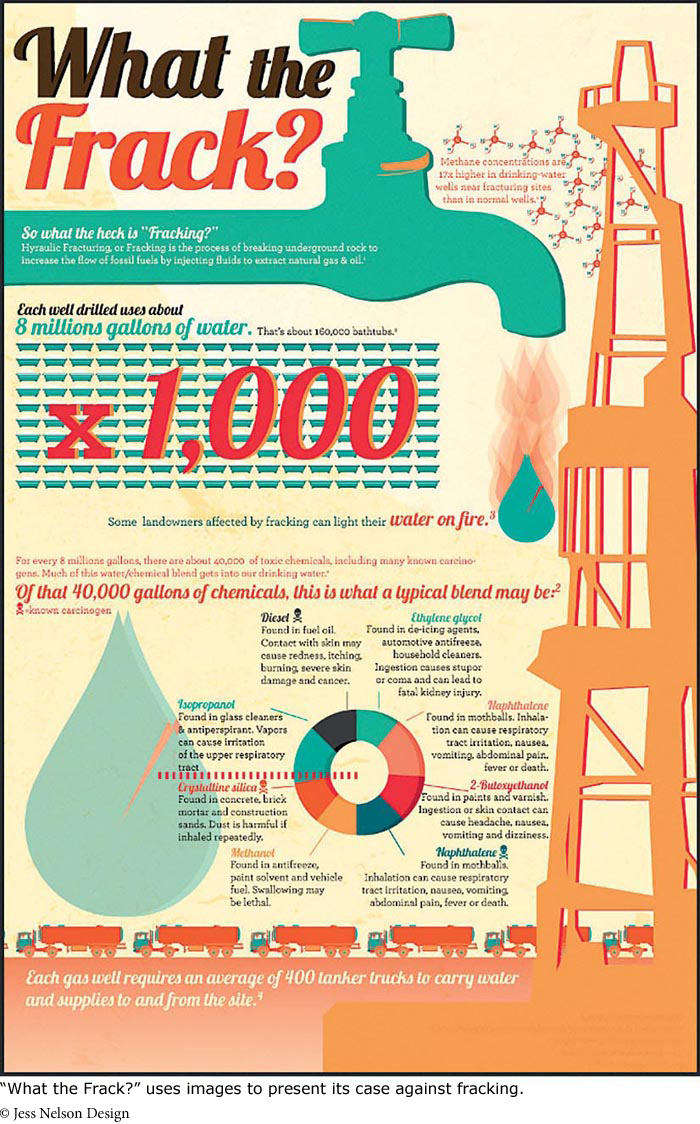

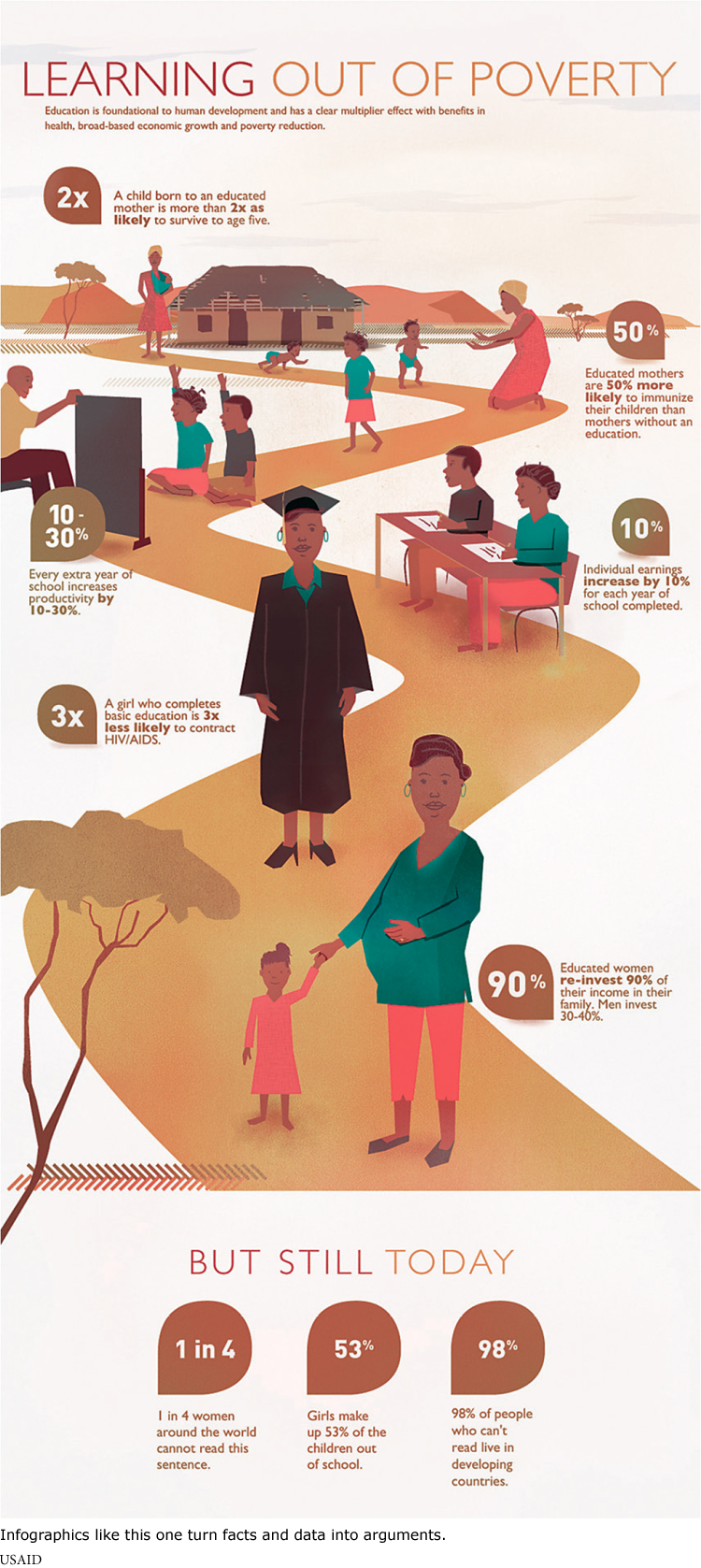

When you prepare a factual argument, consider how you can present your evidence most effectively. Precisely because factual arguments often rely on evidence that can be measured, computed, or illustrated, they benefit from thoughtful, even artful presentation of data. If you have lots of examples, you might arrange them in a list (bulleted or otherwise) and keep the language in each item roughly parallel. If you have an argument that can be translated into a table, chart, or graph (see Chapter 14), try it. And if there’s a more dramatic medium for your factual argument — a Prezi slide show, a multimedia mashup, a documentary video posted via a social network — experiment with it, checking to be sure it would satisfy the assignment.

For an example of how to use design and visuals in a factual argument, see the annotated metadata screenshot in “What Your Email Metadata Told the NSA about You” by Rebecca Greenfield. How does design reinforce the argument?

Images and photos — from technical illustrations to imaginative re-creations — have the power to document what readers might otherwise have to imagine, whether actual conditions of drought, poverty, or a disaster like devastating typhoon Haiyan that displaced over 4 million people in the Philippines in 2013, or the dimensions of the Roman forum as it existed in the time of Julius Caesar. Readers today expect the arguments they read to include visual elements, and there’s little reason not to offer this assistance if you have the technical skills to create them.

Consider the rapid development of the genre known as infographics — basically data presented in bold visual form. These items can be humorous and creative, but many, such as “Learning Out of Poverty,” above, make powerful factual arguments even when they leave it to viewers to draw their own conclusions. Just search “infographics” on the Web to find many examples.