What the Numbers Show about N.F.L. Player Arrests

What the Numbers Show about N.F.L. Player Arrests

NEIL IRWIN

180

Off-the-field violence by professional football players is coming under new focus this week after the release of a video involving the star Baltimore Ravens running back Ray Rice, followed by a bungled response by the National Football League.

But what do the numbers show about N.F.L. players’ tangles with the law more broadly? Are some teams’ players more likely to get into legal trouble? Are arrests rising or falling? What are the most common offenses?

USA Today maintains a database of arrests, charges, and citations of N.F.L. players for anything more serious than a traffic citation. Maintained by Brent Schrotenboer, it goes back to 2000 and covers, to date, 713 instances in which pro football players have had a run-in with the law that was reported by the news media.

181

The data set is imperfect; after all, it depends on news media outlets finding out about every time a third-string offensive lineman is pulled over for driving drunk, and so some arrests may well fall through the cracks. Moreover, arrests are included even if charges are dropped or the player is found not guilty, so it presumably includes legal run-ins in which the player did nothing wrong.

Finally, for purposes of these tabulations, a simple drug possession charge in which no one was hurt counts the same as a case like that of Mr. Rice, who is on tape punching his fiancée out cold (she is now his wife), or even that of the former New England Patriot Aaron Hernandez, who is in jail awaiting trial on murder charges.

But with those caveats aside, here’s what the data show about how pro football players are interacting with the law. The numbers show a league in which drunk-driving arrests are a continuing problem and domestic violence charges are surprisingly common; in which the teams that have the most players getting in legal trouble don’t always fit the impressions fans might have; and in which teams with high arrest rates tend to stay that way over time.

One N.F.L. player in 40 is arrested in a given year. There are 32 teams, each with 53 players on its roster plus another eight on its practice squad (plus more players who show up for training camp but do not make the team, but we didn’t attempt to account for them). Thus over the nearly 15 years that the USA Today data goes back, the 713 arrests mean that 2.53 percent of players have had a serious run-in with the law in an average year. That may sound bad, but the arrest rate is lower than the national average for men in that age range.

Arrests peaked in the mid-2000s, and are way down this year. The peak year for arrests of N.F.L. players was 2006, followed closely by 2007 and 2008. (These are calendar years, not N.F.L. seasons.) One important caveat: The apparent increase could be a result of increased coverage of professional athletes’ legal troubles by Internet media. In other words, we don’t know for sure whether more N.F.L. players were being arrested in those years, or whether TMZ and other outlets were better positioned to find out about it.

Despite the Ray Rice episode, 2014 is on track to be the year with the fewest arrests of N.F.L. players on record. Through Sept. 10, there had only been 21. If the final four months of the year proceed at the same pace of arrests as the first eight, that will come to 28, well below the previous low of 36 in 2004.

182

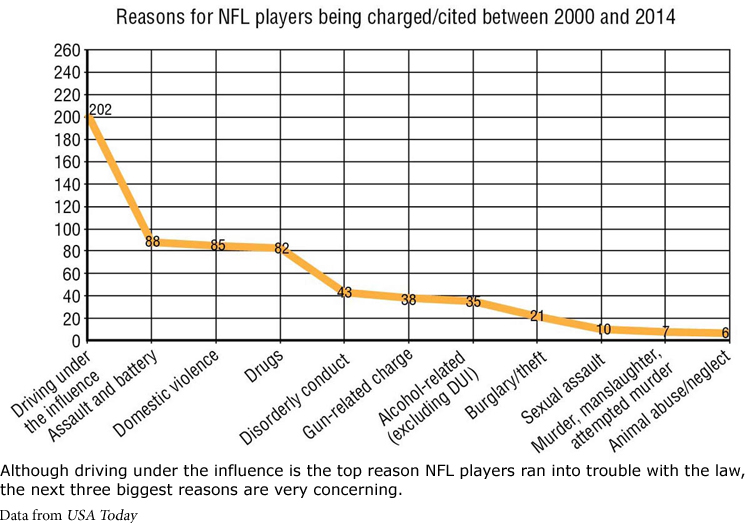

The most common accusation is driving while drunk, but domestic violence is a big problem. Some 28 percent of the arrests in the database were for driving under the influence, with 202 incidents. Other frequent categories of charges include assault and battery (88 cases) and drug-related offenses (82). This data is also a reminder that domestic violence has been a problem among N.F.L. players since long before Ray and Janay Rice got on that Atlantic City elevator: There have been 85 charges for domestic violence and related offenses since 2000.

The Minnesota Vikings have had the most players arrested since 2000. The number of arrests by team range from a low of 11 (tie between the Arizona Cardinals and St. Louis Rams) versus a high of 44 (the Vikings), with the Cincinnati Bengals and Denver Broncos close behind. (The Houston Texans also have 11 but started playing in 2002.)

To look at it a different way, across the league from 2000 through 2013, 2.53 percent of players were arrested per year, but for the Vikings, that number is 5 percent. For the teams tied for fewest arrests, it is 1.3 percent.

183

The Ravens have received negative publicity over Rice, whom they fired, and over other players’ legal troubles this year, but their 22 player arrests since 2000 make them right at the leaguewide average. The Oakland Raiders have cultivated an image of being a franchise for tough, rowdy bad boys. The team’s players, however, have had 19 scrapes with the law since 2000, below average.

The frequency of arrests in a franchise tends to be consistent over time. One might imagine that the number of players from a given franchise who are arrested is a random phenomenon. Maybe, in the rankings above, for example, the Vikings and the Bengals were just unlucky and the Cardinals and Rams were just lucky.

But there’s a simple way to test that. If the results were random, you would expect there to be no correlation between the number of player arrests in one time period with a subsequent time period. You could even imagine a negative correlation, if teams that had a run of players getting in trouble took extra care not to sign players reputed to have character issues.

But that is not what happened over the last 14 years. If you chart the number of arrests of players from each franchise in the first seven years of the data, 2000 to 2006, versus the number of arrests that franchise experienced from 2007 to 2013, the correlation is a pretty solid 53 percent. [This] shows a clear pattern in which those franchises with high numbers of arrests in the early years also tended to have high numbers of arrests in later years and vice versa.

The data don’t tell us anything about why these patterns are so persistent, but there are two possibilities that seem to stand out. First, there could be club culture. The top management of a franchise may send a message to personnel scouts and coaches that they are either more or less tolerant of signing players who have had legal problems in the past. (One might imagine that the personal style of the coach could play a role as well, but coaches tend not to have long tenures in the modern N.F.L.; no coach has led his team continuously for the entirety of the time covered by this arrest data, though the Patriots’ Bill Belichick misses that honor by only a few weeks, having been hired in late January 2000.)

184

Second, there is geography. Different cities have different patterns of living and different approaches to law enforcement. Perhaps players for the Jets and the Giants (both with persistently low arrest rates) are at less risk of arrest for D.U.I. because people are less likely to need to drive themselves to nightclubs in Manhattan. Or perhaps in some cities, young African-American men driving expensive cars attract more police attention than in others.

Regardless of the reasons, a handful of franchises have persistently higher numbers of players who end up being arrested, and may want to learn from their rivals in other cities as to why.