Developing an Evaluative Argument

Developing an Evaluative Argument

Developing an argument of evaluation can seem like a simple process, especially if you already know what your claim is likely to be. To continue the movie theme for one more example:

Citizen Kane is the finest film ever made by an American director.

Having established a claim, you would then explore the implications of your belief, drawing out the reasons, warrants, and evidence that might support it:

Claim |

Citizen Kane is the finest film ever made by an American director . . . |

Reason |

. . . because it revolutionizes the way we see the world. |

Warrant |

Great films change viewers in fundamental ways. |

Evidence |

Shot after shot, Citizen Kane presents the life of its protagonist through cinematic images that viewers can never forget. |

The warrant here is, in effect, an implied statement of criteria — in this case, the quality that defines “great film” for the writer. It may be important for the writer to share that assumption with readers and perhaps to identify other great films that similarly make viewers appreciate new perspectives.

As you can see, in developing an evaluative argument, you’ll want to pay special attention to criteria, claims, and evidence.

Formulating Criteria

Although even casual evaluations (The band sucks!) might be traced to reasonable criteria, most people don’t defend their positions until they are challenged (Oh yeah?). Similarly, writers who address readers with whom they share core values rarely discuss their criteria in great detail. A film critic like the late Roger Ebert (see “Qualitative Evaluations” in Chapter 10, “Evaluations”) isn’t expected to restate all his principles every time he writes a movie review. Ebert assumes that his readers will — over time — come to appreciate his standards. Still, criteria can make or break a piece.

What criteria do Barbara Kingsolver and Steven L. Hopp use to distinguish heirloom tomatoes from those normally found in the grocery store? What arguments do their criteria support?

So spend time developing your criteria of evaluation. What exactly makes a shortstop an all-star? Why is a standardized test an unreliable measure of intelligence? Fundamentally, what distinguishes an inspired rapper from a run-of-the-mill one? List the possibilities and then pare them down to the essentials. If you offer vague, dull, or unsupportable principles, expect to be challenged.

You’re most likely to be vague about your beliefs when you haven’t thought (or read) enough about your subject. Push yourself at least as far as you imagine readers will. Anticipate readers looking over your shoulder, asking difficult questions. Say, for example, that you intend to argue that anyone who wants to stay on the cutting edge of personal technology will obviously want Apple’s latest iPad because it does so many amazing things. But what does that mean exactly? What makes the device “amazing”? Is it that it gives access to email and the Web, has a high-resolution screen, offers an astonishing number of apps, and makes a good e-reader? These are particular features of the device. But can you identify a more fundamental quality to explain the product’s appeal, such as an iPad user’s experience, enjoyment, or feeling of productivity? You’ll often want to raise your evaluation to a higher level of generality like this so that your appraisal of a product, book, performance, or political figure works as a coherent argument, and not just as a list of random observations.

Be certain, too, that your criteria of evaluation apply to more than just your topic of the moment. Your standards should make sense on their own merits and apply across the board. If you tailor your criteria to get the outcome you want, you are doing what is called “special pleading.” You might be pleased when you prove that the home team is awesome, but it won’t take skeptics long to figure out how you’ve cooked the books.

RESPOND •

Local news and entertainment magazines often publish “best of” issues or articles that catalog their readers’ and editors’ favorites in such categories as “best place to go on a first date,” “best ice cream sundae,” and “best dentist.” Sometimes the categories are specific: “best places to say ‘I was retro before retro was cool’” or “best movie theater seats.” Imagine that you’re the editor of your own local magazine and that you want to put out a “best of” issue tailored to your hometown. Develop ten categories for evaluation. For each category, list the evaluative criteria that you would use to make your judgment. Next, consider that because your criteria are warrants, they’re especially tied to audience. (The criteria for “best dentist,” for example, might be tailored to people whose major concern is avoiding pain, to those whose children will be regular patients, or to those who want the cheapest possible dental care.) For several of the evaluative categories, imagine that you have to justify your judgments to a completely different audience. Write a new set of criteria for that audience.

Making Claims

In evaluations, claims can be stated directly or, more rarely, strongly implied. For most writers, strong statements followed by reasonable qualifications work best. Consider the differences between the following three claims and how much greater the burden of proof is for the first claim:

Jessica Williams is the funniest “correspondent” ever on The Daily Show.

Jessica Williams has emerged as one of the funniest of The Daily Show’s “correspondents.”

Jessica Williams may come to be regarded as one of the funniest and most successful of the “correspondents” on The Daily Show.

Here’s a second set of examples demonstrating the same principle, that qualifications generally make a claim of evaluation easier to deal with and smarter:

The Common Core Standards movement sure is a dumb idea.

The Common Core Standards movement in educational reform is likely to do more harm than good.

While laudable in their intentions to raise standards and improve student learning, the Common Core Standards adopted throughout the United States continue to put so high a premium on testing that they may well undermine the goals they seek to achieve.

The point of qualifying a statement isn’t to make evaluative claims bland but to make them responsible and reasonable. Consider how Reagan Tankersley uses the criticisms of a musical genre he enjoys to frame a claim he makes in its defense:

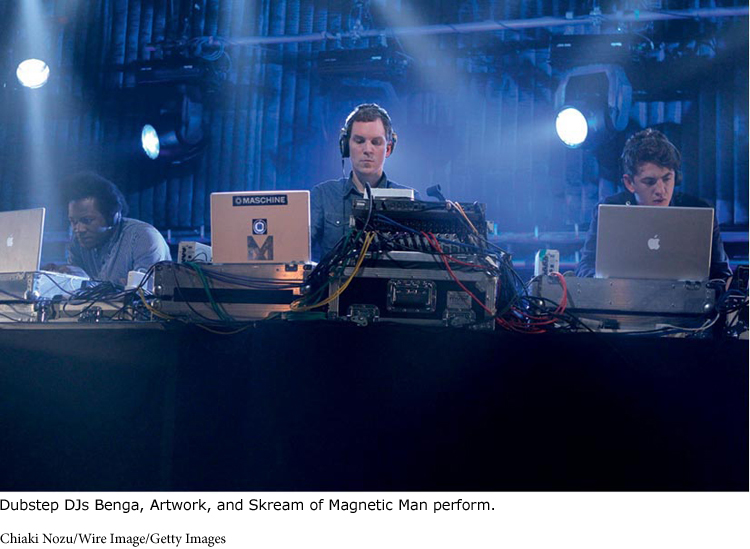

Structurally, dubstep is a simple musical form, with formulaic progressions and beats, something that gives a musically tuned ear little to grasp or analyze. For this reason, a majority of traditionally trained musicians find the genre to be a waste of time. These people have a legitimate position. . . . However, I hold that it is the simplicity of dubstep that makes it special: the primal nature of the song is what digs so deeply into fans. It accesses the most primitive area in our brains that connects to the uniquely human love of music.

— Reagan Tankersley, “Dubstep: Why People Dance”

Tankersley doesn’t pretend that dubstep is something it’s not, nor does he expect his argument to win over traditionally minded critics. Yet he still makes a claim worth considering.

One tip: Nothing adds more depth to an opinion than letting others challenge it. When you can, use the resources of the Internet or local discussion boards to get responses to your opinions or topic proposals. It can be eye-opening to realize how strongly people react to ideas or points of view that you regard as perfectly normal. Share your claim and then, when you’re ready, your first draft with friends and classmates, asking them to identify places where your ideas need additional support, either in the discussion of criteria or in the presentation of evidence.

Presenting Evidence

Generally, the more evidence in an evaluation the better, provided that the evidence is relevant. For example, in evaluating the performance of two laptops, the speed of their processors would be essential; the quality of their keyboards or the availability of service might be less crucial yet still worth mentioning. But you have to decide how much detail your readers want in your argument. For technical subjects, you might make your basic case briefly and then attach additional supporting documents at the end — tables, graphs, charts — for those who want more data.

Sheryll Cashin analyzes the implications of affirmative action in the introduction to her book Place, Not Race: A New Vision of Opportunity in America. What evidence does she use to support her stance that the system is broken?

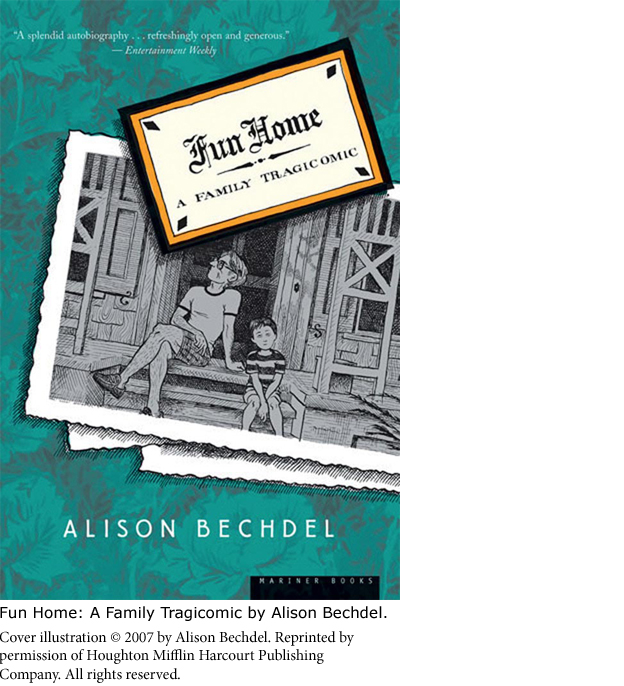

Just as important as relevance in selecting evidence is presentation. Not all pieces of evidence are equally convincing, nor should they be treated as such. Select evidence that is most likely to influence your readers, and then arrange the argument to build toward your best material. In most cases, that best material will be evidence that’s specific, detailed, memorable, and derived from credible sources. The details in these paragraphs from Sean Wilsey’s review of Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic, a graphic novel by Alison Bechdel, tell you precisely what makes the work “lush,” “absorbing,” and well worth reading:

It is a pioneering work, pushing two genres (comics and memoir) in multiple new directions, with panels that combine the detail and technical proficiency of R. Crumb with a seriousness, emotional complexity, and innovation completely its own. Then there are the actual words. Generally this is where graphic narratives stumble. Very few cartoonists can also write — or, if they can, they manage only to hit a few familiar notes. But Fun Home quietly succeeds in telling a story, not only through well-crafted images but through words that are equally revealing and well chosen. Big words, too! In 232 pages this memoir sent me to the dictionary five separate times (to look up “bargeboard,” “buss,” “scutwork,” “humectant,” and “perseverated”).

A comic book for lovers of words! Bechdel’s rich language and precise images combine to create a lush piece of work — a memoir where concision and detail are melded for maximum, obsessive density. She has obviously spent years getting this memoir right, and it shows. You can read Fun Home in a sitting, or get lost in the pictures within the pictures on its pages. The artist’s work is so absorbing you feel you are living in her world.

— Sean Wilsey, “The Things They Buried”

The details in this passage make the case that Alison Bechdel’s novel is one that pushes both comics and memoirs in new directions.

In evaluation arguments, don’t be afraid to concede a point when evidence goes contrary to the overall claim you wish to make. If you’re really skillful, you can even turn a problem into an argumentative asset, as Bob Costas does in acknowledging the flaws of baseball great Mickey Mantle in the process of praising him:

None of us, Mickey included, would want to be held to account for every moment of our lives. But how many of us could say that our best moments were as magnificent as his?

— Bob Costas, “Eulogy for Mickey Mantle”

RESPOND •

Take a close look at the cover of Alison Bechdel’s graphic novel Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic. In what various ways does it make an argument of evaluation designed to make you want to read the work? Examine other books, magazines, or media packages (such as video game or software boxes) and describe any strategies they use to argue for their merit.

Considering Design and Visuals

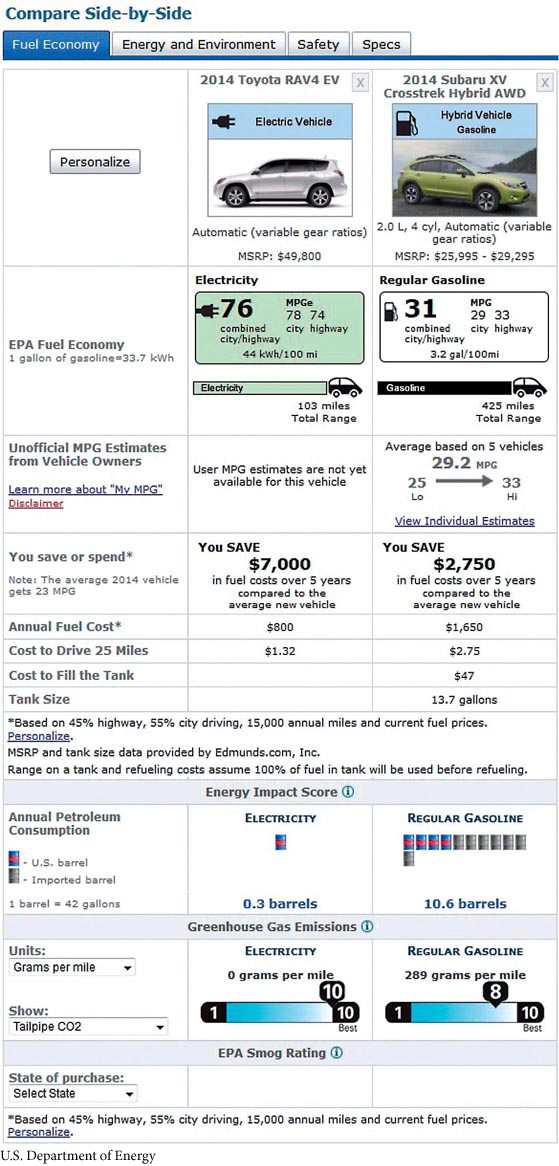

Visual components play a significant role in many arguments of evaluation, especially those based on quantitative information. As soon as numbers are involved in supporting a claim, think about ways to arrange them in tables, charts, graphs, or infographics to make the information more accessible to readers. Visual elements are especially helpful when comparing items. Indeed, a visual spread like the one in the federal government’s comparison of electric and hybrid cars becomes an argument in itself about the vehicles the government has analyzed for fuel economy. The facts seem to speak for themselves because they are presented with care and deliberation. In the same way, you will want to make sure that you use similar care when using visuals to inform and persuade readers.

But don’t ignore other basic design features of a text — such as headings for the different criteria you’re using or, in online evaluations, links to material related to your subject.