Can a Playground Be Too Safe?

Can a Playground Be Too Safe?

JOHN TIERNEY

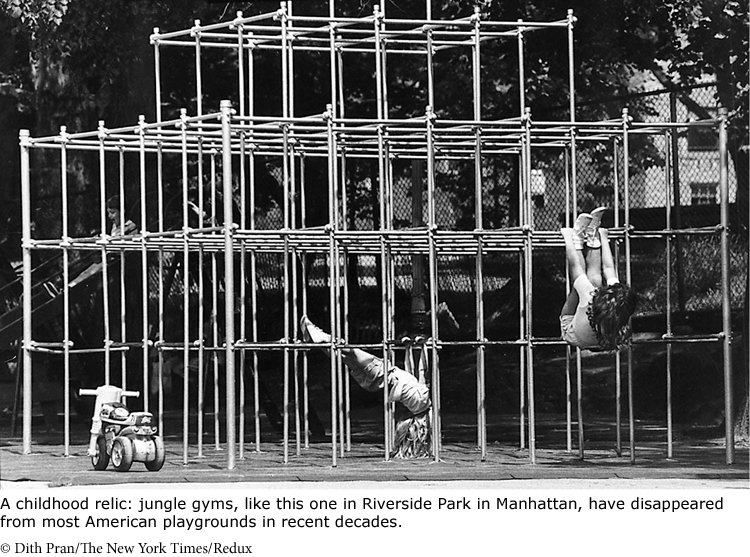

When seesaws and tall slides and other perils were disappearing from New York’s playgrounds, Henry Stern drew a line in the sandbox. As the city’s parks commissioner in the 1990s, he issued an edict concerning the ten-foot-high jungle gym near his childhood home in northern Manhattan.

“I grew up on the monkey bars in Fort Tryon Park, and I never forgot how good it felt to get to the top of them,” Mr. Stern said. “I didn’t want to see that playground bowdlerized. I said that as long as I was parks commissioner, those monkey bars were going to stay.”

His philosophy seemed reactionary at the time, but today it’s shared by some researchers who question the value of safety-first playgrounds. Even if children do suffer fewer physical injuries — and the evidence for that is debatable — the critics say that these playgrounds may stunt emotional development, leaving children with anxieties and fears that are ultimately worse than a broken bone.

“Children need to encounter risks and overcome fears on the playground,” said Ellen Sandseter, a professor of psychology at Queen Maud University in Norway. “I think monkey bars and tall slides are great. As playgrounds become more and more boring, these are some of the few features that still can give children thrilling experiences with heights and high speed.”

After observing children on playgrounds in Norway, England, and Australia, Dr. Sandseter identified six categories of risky play: exploring heights, experiencing high speed, handling dangerous tools, being near dangerous elements (like water or fire), rough-and-tumble play (like wrestling), and wandering alone away from adult supervision. The most common is climbing heights.

“Climbing equipment needs to be high enough, or else it will be too boring in the long run,” Dr. Sandseter said. “Children approach thrills and risks in a progressive manner, and very few children would try to climb to the highest point for the first time they climb. The best thing is to let children encounter these challenges from an early age, and they will then progressively learn to master them through their play over the years.”

Sometimes, of course, their mastery fails, and falls are the common form of playground injury. But these rarely cause permanent damage, either physically or emotionally. While some psychologists — and many parents — have worried that a child who suffered a bad fall would develop a fear of heights, studies have shown the opposite pattern: A child who’s hurt in a fall before the age of nine is less likely as a teenager to have a fear of heights.

By gradually exposing themselves to more and more dangers on the playground, children are using the same habituation techniques developed by therapists to help adults conquer phobias, according to Dr. Sandseter and a fellow psychologist, Leif Kennair, of the Norwegian University for Science and Technology.

“Risky play mirrors effective cognitive behavioral therapy of anxiety,” they write in the journal Evolutionary Psychology, concluding that this “anti-phobic effect” helps explain the evolution of children’s fondness for thrill-seeking. While a youthful zest for exploring heights might not seem adaptive — why would natural selection favor children who risk death before they have a chance to reproduce? — the dangers seemed to be outweighed by the benefits of conquering fear and developing a sense of mastery.

“Paradoxically,” the psychologists write, “we posit that our fear of children being harmed by mostly harmless injuries may result in more fearful children and increased levels of psychopathology.”

The old tall jungle gyms and slides disappeared from most American playgrounds across the country in recent decades because of parental concerns, federal guidelines, new safety standards set by manufacturers and — the most frequently cited factor — fear of lawsuits.

Shorter equipment with enclosed platforms was introduced, and the old pavement was replaced with rubber, wood chips, or other materials designed for softer landings. These innovations undoubtedly prevented some injuries, but some experts question their overall value.

“There is no clear evidence that playground safety measures have lowered the average risk on playgrounds,” said David Ball, a professor of risk management at Middlesex University in London. He noted that the risk of some injuries, like long fractures of the arm, actually increased after the introduction of softer surfaces on playgrounds in Britain and Australia.

“This sounds counterintuitive, but it shouldn’t, because it is a common phenomenon,” Dr. Ball said. “If children and parents believe they are in an environment which is safer than it actually is, they will take more risks. An argument against softer surfacing is that children think it is safe, but because they don’t understand its properties, they overrate its performance.”

Reducing the height of playground equipment may help toddlers, but it can produce unintended consequences among bigger children. “Older children are discouraged from taking healthy exercise on playgrounds because they have been designed with the safety of the very young in mind,” Dr. Ball said. “Therefore, they may play in more dangerous places, or not at all.”

Fear of litigation led New York City officials to remove seesaws, merry-go-rounds, and the ropes that young Tarzans used to swing from one platform to another. Letting children swing on tires became taboo because of fears that the heavy swings could bang into a child.

“What happens in America is defined by tort lawyers, and unfortunately that limits some of the adventure playgrounds,” said Adrian Benepe, the current parks commissioner. But while he misses the Tarzan ropes, he’s glad that the litigation rate has declined, and he’s not nostalgic for asphalt pavement.

“I think safety surfaces are a godsend,” he said. “I suspect that parents who have to deal with concussions and broken arms wouldn’t agree that playgrounds have become too safe.” The ultra-safe enclosed platforms of the 1980s and 1990s may have been an overreaction, Mr. Benepe said, but lately there have been more creative alternatives.

“The good news is that manufacturers have brought out new versions of the old toys,” he said. “Because of height limitations, no one’s building the old monkey bars anymore, but kids can go up smaller climbing walls and rope nets and artificial rocks.”

Still, sometimes there’s nothing quite like being ten feet off the ground, as a new generation was discovering the other afternoon at Fort Tryon Park. A soft rubber surface carpeted the pavement, but the jungle gym of Mr. Stern’s youth was still there. It was the prime destination for many children, including those who’d never seen one before, like Nayelis Serrano, a ten-year-old from the South Bronx who was visiting her cousin.

When she got halfway up, at the third level of bars, she paused, as if that was high enough. Then, after a consultation with her mother, she continued to the top, the fifth level, and descended to recount her triumph.

“I was scared at first,” she explained. “But my mother said if you don’t try, you’ll never know if you could do it. So I took a chance and kept going. At the top I felt very proud.” As she headed back for another climb, her mother, Orkidia Rojas, looked on from a bench and considered the pros and cons of this unfamiliar equipment.

“It’s fun,” she said. “I’d like to see it in our playground. Why not? It’s kind of dangerous, I know, but if you just think about danger you’re never going to get ahead in life.”

John Tierney is a journalist and coauthor of the book Willpower: Rediscovering the Greatest Human Strength (2011). He writes the science column “Findings” for the New York Times, where this piece was originally published on July 18, 2011. You will note that, as a journalist, Tierney cites sources without documenting them formally. An academic version of this argument might offer both in-text citations and a list of sources at the end.