Understanding and Categorizing Proposals

Understanding and Categorizing Proposals

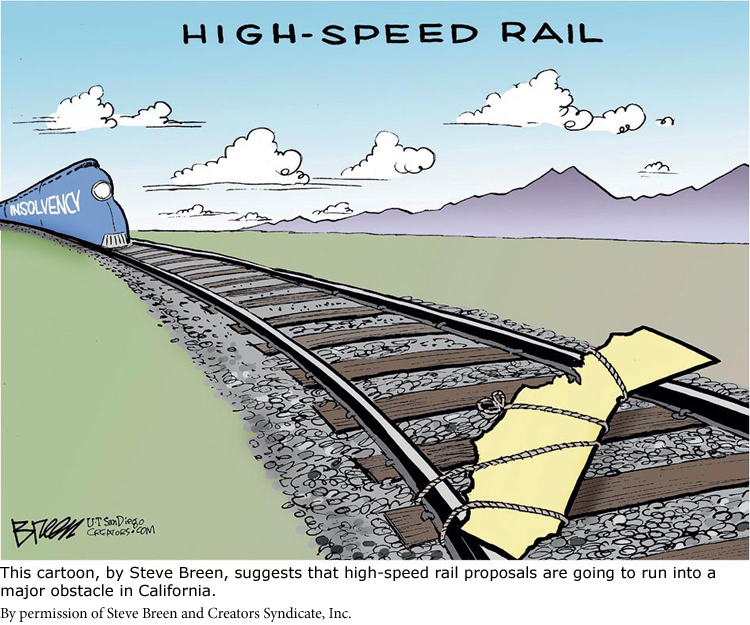

We live in an era of big proposals — complex programs for health care reform, bold dreams to privatize space exploration, multibillion-dollar designs for high-speed rail systems, ceaseless calls to improve education, and so many other such ideas brought down to earth by sobering proposals for budget reform and deficit reduction. As a result, there’s often more talk than action because persuading people (or legislatures) to do something — or anything! — is always hard. But that’s what proposal arguments do: they provide thoughtful reasons for supporting or sometimes resisting change.

Such arguments, whether national or local, formal or casual, are important not only on the national scene but also in all of our lives. How many proposals do you make or respond to in one day? A neighbor might suggest that you volunteer to help clean up an urban creek bed; a campus group might demand that students get better seats at football games; a supervisor might ask for ideas to improve customer satisfaction at a restaurant; you might offer an ad agency reasons to hire you as a summer intern — or propose to a friend that you take in the latest zombie film. In each case, the proposal implies that some action should take place and suggests that there are sound reasons why it should.

In their simplest form, proposal arguments look something like this:

Proposals come at us so routinely that it’s not surprising that they cover a dizzyingly wide range of possibilities. So it may help to think of proposal arguments as divided roughly into two kinds — those that focus on specific practices and those that focus on broad matters of policy. Here are several examples of each kind:

Proposals about Practices

The college should allow students to pay tuition on a month-by-month basis.

Commercial hotels should stop opposing competitors like Airbnb.

College athletes should be paid for the services they provide.

Proposals about Policies

The college should adopt a policy guaranteeing that students in all majors can graduate in four years.

The United Nations should make saving the oceans from pollution a global priority.

Major Silicon Valley firms should routinely reveal the demographic makeup of their workforces.

RESPOND •

People write proposal arguments to solve problems and to change the way things are. But problems aren’t always obvious: what troubles some people might be no big deal to others. To get an idea of the range of problems people face on your campus (some of which you may not even have thought of as problems), divide into groups, and brainstorm about things that annoy you on and around campus, including wastefulness in the cafeterias, 8:00 a.m. classes, and long lines for football or concert tickets. Ask each group to aim for at least a dozen gripes. Then choose three problems, and as a group, discuss how you’d prepare a proposal to deal with them.