Style in Arguments

13

Style in Arguments

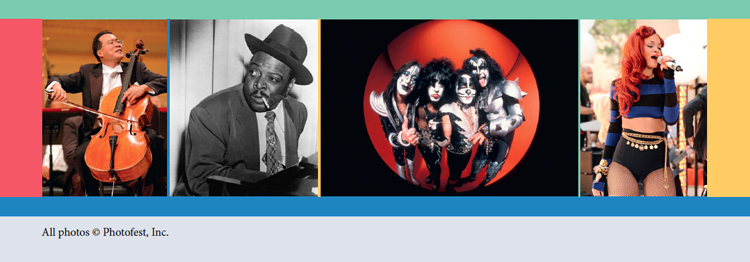

The images above all reflect the notable styles of musicians from different times and musical traditions: Yo-Yo Ma, Count Basie, Kiss, and Rihanna. One could argue that these performers craft images to define their stage personalities, but how they present themselves also reflects the music they play and the audiences they perform for. Imagine Yo-Yo Ma appearing in Kiss makeup at Carnegie Hall. It doesn’t work.

Writers, too, like to think of themselves as creating styles that express their ethos and life experiences — and they do. But in persuasive situations, style is also a matter of the specific choices they make — strategically and self-consciously — to influence audiences.

So it’s not surprising that writers adapt their voices to a range of rhetorical situations, from very formal to very casual. At the formal and professional end of the scale, consider the opening paragraph of a dissent by Justice Sonia Sotomayor to a Supreme Court decision affecting affirmative action in Michigan public universities. Writing doesn’t get much more consequential than this, and that earnestness is reflected in the justice’s sober, authoritative, but utterly clear style:

We are fortunate to live in a democratic society. But without checks, democratically approved legislation can oppress minority groups. For that reason, our Constitution places limits on what a majority of the people may do. This case implicates one such limit: the guarantee of equal protection of the laws. Although that guarantee is traditionally understood to prohibit intentional discrimination under existing laws, equal protection does not end there. Another fundamental strand of our equal protection jurisprudence focuses on process, securing to all citizens the right to participate meaningfully and equally in self-government. That right is the bedrock of our democracy, for it preserves all other rights.

— Sonia Sotomayor, dissenting opinion, April 22, 2014

Contrast this formal style (perhaps the equivalent of Yo-Yo Ma’s tuxedo?) to the more personal language Alexis C. Madrigal uses in an article for the Atlantic to argue that we are finally tiring of the relentless “stream” of information pouring down on us via social media. His subject is serious and his readers are too, but Madrigal employs a rougher style to express the resentment of people he sees as victimized by a once-promising technology that trivializes everything:

Nowadays, I think all kinds of people see and feel the tradeoffs of the stream, when they pull their thumbs down at the top of their screens to receive a new update from their social apps.

It is too damn hard to keep up. And most of what’s out there is crap.

When the half-life of a post is half a day or less, how much time can media makers put into something? When the time a reader spends on a story is (on the high end) two minutes, how much time should media makers put into something?

— Alexis C. Madrigal, “2013: The Year ‘the Stream’ Crested”

Just a paragraph later, Madrigal again tunes his style to accommodate both high and low notes (maybe riffing like Count Basie?). First, he alludes to one of the toughest novels of the twentieth century, and then he chooses sentence structures — a fragment followed by two very short, emphatic, not-quite-parallel clauses — to mark the contrast between the formidable book and social media:

I am not joking when I say: it is easier to read Ulysses than it is to read the Internet. Because at least Ulysses has an end, an edge. Ulysses can be finished. The Internet is never finished.

Far more casual in subject matter and style is a blog item by Huffington Post book editor Claire Fallon, arguing (tongue-in-cheek) that Shakespeare’s Romeo is one of those literary figures readers just love to hate. The range of Fallon’s vocabulary choices — from “most romantic dude” to “penchant for wallowing” — suggests the (Rihanna-like?) playfulness of the exercise. Style is obviously a big part of Fallon’s game:

Romeo, Romeo, wherefore art thou such a wishy-washy doofus? Shakespeare himself would likely be baffled by the elevation of Romeo to the position of “most romantic dude in literature” — he spends his first scene in the play insisting he’s heartbroken over a girl he goes on to completely forget about the second he catches a glimpse of Juliet! Poor Rosaline (or rather, nice bullet-dodging, Rosaline). Romeo’s apparent penchant for wallowing in the romantic misery of unrequited love finds a new target in naive Juliet, who then dies for a guy who probably would have forgotten about her as soon as their honeymoon ended. Yes, Romeo is self-absorbed, fickle, and rather whiny, but we clearly love him anyway.

— Claire Fallon, “11 Unlikeable Classical Book Characters We Love to Hate”

As you might guess from these examples, style always involves making choices about language across a wide range of situations. Style can be public or personal, conventional or creative, and everything in between. When you write, you’ll find that you have innumerable tools and options for expressing yourself exactly as you need to. This chapter introduces you to some of them.