New Audiences in New Media

New Audiences in New Media

When it comes to making arguments, perhaps the most innovative aspect of new media is its ability to summon audiences. Since ancient times (see “Appealing to Audiences” in Chapter 1, “Everything's an Argument”), rhetoricians have emphasized the need to frame arguments to influence people, but new media and social networks now create places for specific audiences to emerge and make the arguments themselves, assembling them in bits and pieces, one comment or supporting link at a time. Audiences muster around sites that represent their perspectives on politics or mirror their social conditions and interests.

“It’s Not OK Cupid: Co-Founder Defends User Experiments” is aimed at an audience made possible by technology: those interested in the phenomenon of online dating.

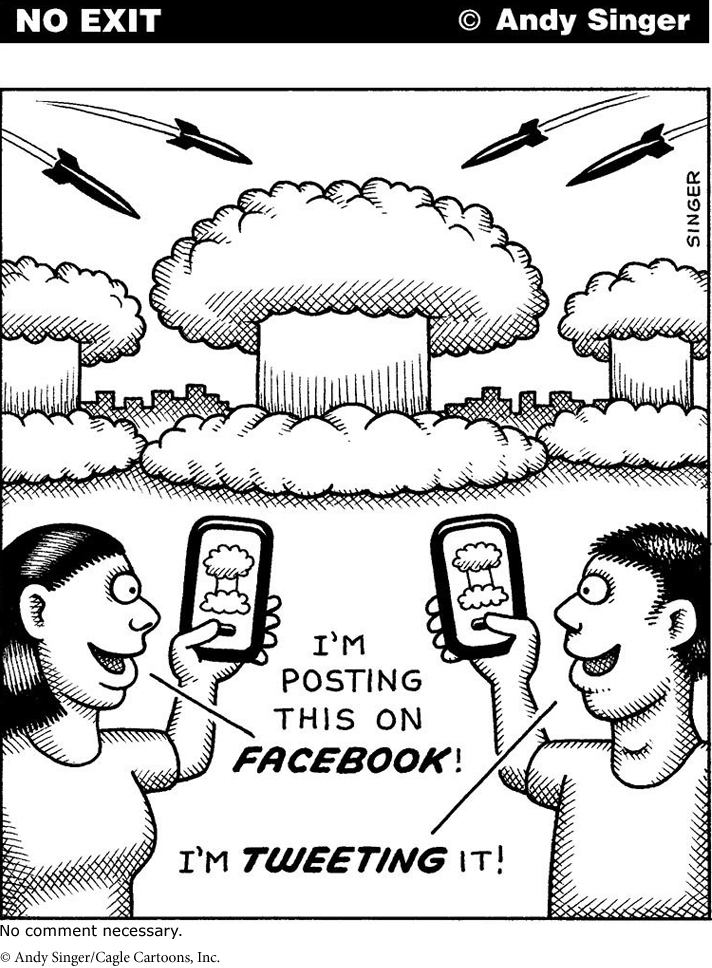

It seems natural. Democrats engage with different blog sites than do Libertarians; champions of immigration or gun rights advocates have their favored places too. Within social networks themselves, supporters of causes can join existing activist communities or create new alliances among people with compatible views. And then all those individuals contribute to the never-ending newsfeeds: links, favorite books and authors, preferred images or slogans, illustrative videos, and so on. They stir the pot and generate still more energy, concern, and emotion. It can be very exciting or begin to sound like an echo chamber. But activity within virtual communities itself is potent and powerful. Some have attributed President Obama’s second-term electoral victory, in part, to the buzz his campaign generated within social media. These days, assembling an audience may be just as important as making or winning arguments.

That principle may help account for the Twitter phenomenon. There, celebrities and political figures alike, for a wide variety of reasons, attract “followers” cued into their occasional 140-character musings (Hillary Clinton: 1.6M followers; Pope Francis: 4.2M; Taylor Swift: 40M+). In some respects, “following” becomes a measure of ethos, the trust and connection people have in the person offering a point of view (see Chapter 3). Sometimes that ethos is largely just about media fame, but in other cases it may measure genuine influence that public figures have earned by virtue of their ideas or opinions. People who sign on as their followers signal their willingness to listen to their Twitter commentary — ideas they probably agree with already.

But logos would seem to have little chance of emerging in a platform like Twitter: can you do much more than make a bare claim or two in the few words and symbols allowed? That’s where hashtags come in. Hashtags are words prefixed with a # sign in a Twitter posting to identify a topic and place around which an audience may gather. It provides a way of linking related comments within the vast environment or, just as important, drawing audiences to specific ideas. This is the point, for instance, of Mrs. Obama holding up a card with the #BringBackOurGirls hashtag (see the opening photo in Chapter 1, “Everything's an Argument”) — using her ethos to attract an even larger audience to the issue she and many others support. So, once again, the audience in new media becomes a tangible object — its political power evident in the sheer number of people weighing in on controversies, expressing their sentiments succinctly, but also accumulating a sense of direction, solidarity, and gravity. It’s also why political journalists or print publications now routinely identify trending hashtags in their reporting or even direct audiences to Twitter to track breaking stories or social movements as they unfold there.

It’s a kind of suasion Aristotle could not have imagined.