Understanding What Academic Argument Is

Understanding What Academic Argument Is

Academic argument covers a wide range of writing, but its hallmarks are an appeal to reason and a faith in research. As a consequence, such arguments cannot be composed quickly, casually, or off the top of one’s head. They require careful reading, accurate reporting, and a conscientious commitment to truth. But academic pieces do not tune out all appeals to ethos or emotion: today, we know that these arguments often convey power and authority through their impressive lists of sources and their immediacy. But an academic argument crumbles if its facts are skewed or its content proves to be unreliable.

Look, for example, how systematically Susannah Fox and Lee Rainie, director and codirector of the Pew Internet Project, present facts and evidence in arguing that the Internet has been, overall, a big plus for society and individuals alike.

[Today,] 87% of American adults now use the Internet, with near-saturation usage among those living in households earning $75,000 or more (99%), young adults ages 18–29 (97%), and those with college degrees (97%). Fully 68% of adults connect to the Internet with mobile devices like smartphones or tablet computers.

The adoption of related technologies has also been extraordinary: Over the course of Pew Research Center polling, adult ownership of cell phones has risen from 53% in our first survey in 2000 to 90% now. Ownership of smartphones has grown from 35% when we first asked in 2011 to 58% now.

Impact: Asked for their overall judgment about the impact of the Internet, toting up all the pluses and minuses of connected life, the public’s verdict is overwhelmingly positive: 90% of Internet users say the Internet has been a good thing for them personally and only 6% say it has been a bad thing, while 3% volunteer that it has been some of both. 76% of Internet users say the Internet has been a good thing for society, while 15% say it has been a bad thing and 8% say it has been equally good and bad.

—Susannah Fox and Lee Rainie, “The Web at 25 in the U.S.”

Note, too, that these writers draw their material from research and polls conducted by the Pew Research Center, a well-known and respected organization. Chances are you immediately recognize that this paragraph is an example of a researched academic argument.

Nicholas Ostler’s conference paper “Is It Globalization That Endangers Languages?” meets the criteria listed here for academic argument and provides a potential model for your own writing.

You can also identify academic argument by the way it addresses its audiences. Some academic writing is clearly aimed at specialists in a field who are familiar with both the subject and the terminology that surrounds it. As a result, the researchers make few concessions to general readers unlikely to encounter or appreciate their work. You see that single-mindedness in this abstract of an article about migraine headaches in a scientific journal: it quickly becomes unreadable to nonspecialists.

Abstract

Migraine is a complex, disabling disorder of the brain that manifests itself as attacks of often severe, throbbing head pain with sensory sensitivity to light, sound and head movement. There is a clear familial tendency to migraine, which has been well defined in a rare autosomal dominant form of familial hemiplegic migraine (FHM). FHM mutations so far identified include those in CACNA1A (P/Q voltage-gated Ca(2+) channel), ATP1A2 (N(+)-K(+)-ATPase) and SCN1A (Na(+) channel) genes. Physiological studies in humans and studies of the experimental correlate—cortical spreading depression (CSD)—provide understanding of aura, and have explored in recent years the effect of migraine preventives in CSD. . . .

—Peter J. Goadsby, “Recent Advances in Understanding Migraine Mechanisms, Molecules, and Therapeutics,” Trends in Molecular Medicine (January 2007)

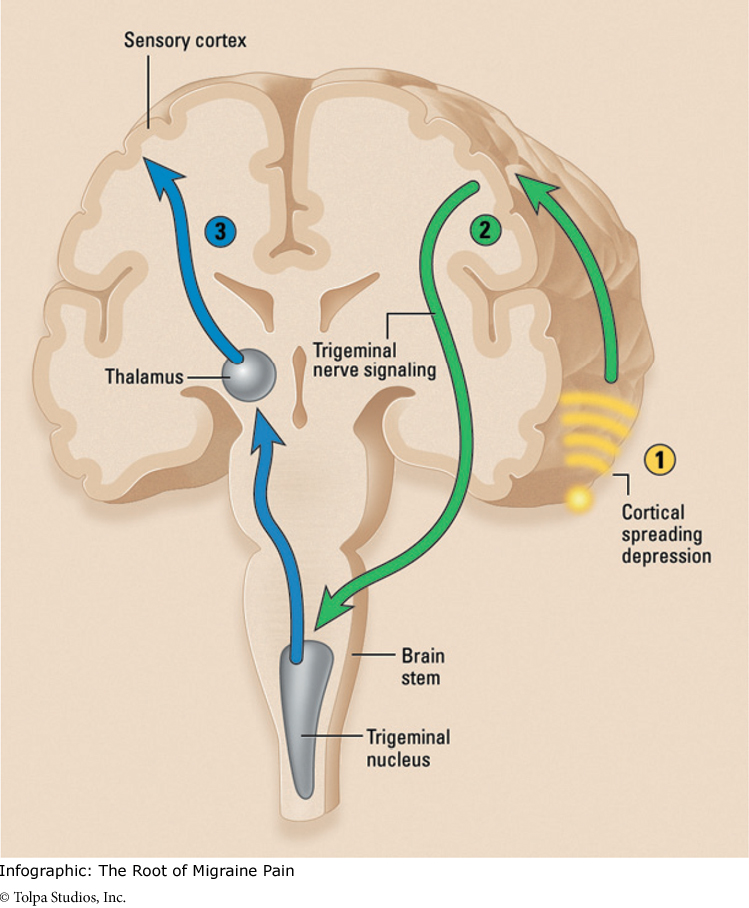

Yet this very article might later provide data for a more accessible argument in a magazine such as Scientific American, which addresses a broader (though no less serious) readership. Here’s a selection from an article on migraine headaches from that more widely read journal (see also the infographic below.)

At the moment, only a few drugs can prevent migraine. All of them were developed for other diseases, including hypertension, depression and epilepsy. Because they are not specific to migraine, it will come as no surprise that they work in only 50 percent of patients—and, in them, only 50 percent of the time—and induce a range of side effects, some potentially serious.

Recent research on the mechanism of these antihypertensive, antiepileptic and antidepressant drugs has demonstrated that one of their effects is to inhibit cortical spreading depression. The drugs’ ability to prevent migraine with and without aura therefore supports the school of thought that cortical spreading depression contributes to both kinds of attacks. Using this observation as a starting point, investigators have come up with novel drugs that specifically inhibit cortical spreading depression. Those drugs are now being tested in migraine sufferers with and without aura. They work by preventing gap junctions, a form of ion channel, from opening, thereby halting the flow of calcium between brain cells.

—David W. Dodick and J. Jay Gargus, “Why Migraines Strike,” Scientific American (August 2008)

Such writing still requires attention, but it delivers important and comprehensible information to any reader seriously interested in the subject and the latest research on it.

Even when academic writing is less technical and demanding, its style will retain a degree of formality. In academic arguments, the focus is on the subject or topic rather than the authors, the tone is straightforward, the language is largely unadorned, and all the i’s are dotted and t’s crossed. Here’s an abstract for an academic paper written by a scholar of communications on the Burning Man phenomenon, demonstrating those qualities:

Every August for more than a decade, thousands of information technologists and other knowledge workers have trekked out into a barren stretch of alkali desert and built a temporary city devoted to art, technology, and communal living: Burning Man. Drawing on extensive archival research, participant observation, and interviews, this paper explores the ways that Burning Man’s bohemian ethos supports new forms of production emerging in Silicon Valley and especially at Google. It shows how elements of the Burning Man world—including the building of a socio-technical commons, participation in project-based artistic labor, and the fusion of social and professional interaction—help shape and legitimate the collaborative manufacturing processes driving the growth of Google and other firms. The paper thus develops the notion that Burning Man serves as a key cultural infrastructure for the Bay Area’s new media industries.

—Fred Turner, “Burning Man at Google: A Cultural Infrastructure for New Media Production”

You might imagine a different and far livelier way to tell a story about the annual Burning Man gathering in Nevada, but this piece respects the conventions of its academic field.

Another way you likely identify academic writing—especially in term papers or research projects—is by the way it draws upon sources and builds arguments from research done by experts and reported in journal articles and books. Using an evenhanded tone and dealing with all points of view fairly, such writing brings together multiple voices and intriguing ideas. You can see these moves in just one paragraph from a heavily documented student essay examining the comedy of Chris Rock:

The breadth of passionate debate that [Chris] Rock’s comedy elicits from intellectuals is evidence enough that he is advancing discussion of the foibles of black America, but Rock continually insists that he has no political aims: “Really, really at the end of the day, the only important thing is being funny. I don’t go out of my way to be political” (qtd. in Bogosian 58). His unwillingness to view himself as a black leader triggers Justin Driver to say, “[Rock] wants to be caustic and he wants to be loved” (32). Even supporters wistfully sigh, “One wishes Rock would own up to the fact that he’s a damned astute social critic” (Kamp 7).

—Jack Chung, “The Burden of Laughter: Chris Rock Fights Ignorance His Way”

Readers can quickly tell that author Jack Chung has read widely and thought carefully about how to support his argument.

As you can see even from these brief examples, academic arguments cover a broad range of topics and appear in a variety of media—as a brief note in a journal like Nature, for example, a poster session at a conference on linguistics, a short paper in Physical Review Letters, a full research report in microbiology, or an undergraduate honors thesis in history. What do all these projects have in common? One professor we know defines academic argument as “carefully structured research,” and that seems to us to be a pretty good definition.

Conventions in Academic Argument Are Not Static

Far from it. In fact, the rise of new technologies and the role that blogs, wikis, social media sites, and other digital discourses play in all our lives are affecting academic writing as well. Thus, scholars today are pushing the envelope of traditional academic writing in some fields. Physicians, for example, are using narrative (rather than charts) more often in medicine to communicate effectively with other medical personnel. Professional journals now sometimes feature serious scholarly work in new formats—such as comics (as in legal scholar Jamie Boyle’s work on intellectual property, or Nick Sousanis’s Columbia University PhD dissertation, which is entirely in comic form). And student writers are increasingly producing serious academic arguments using a wide variety of modalities, including sound, still and moving images, and more.