Considering the Rhetorical Situation

Considering the Rhetorical Situation

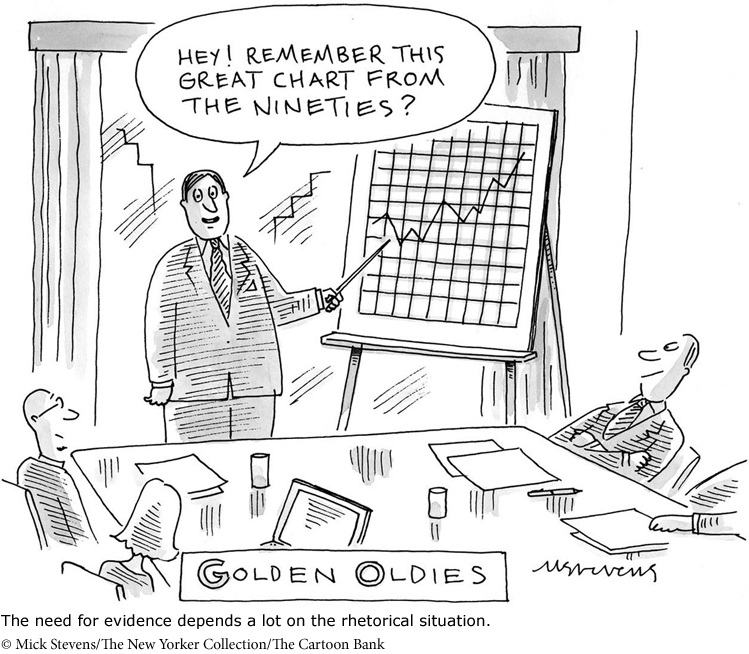

To be most persuasive, evidence should match the time and place in which you make your argument — that is to say, your rhetorical situation. For example, arguing that government officials in the twenty-first century should use the same policies to deal with economic troubles that were employed in the middle of the twentieth might not be convincing on its own. After all, almost every aspect of the world economy has changed in the past fifty years. In the same way, a writer may achieve excellent results by citing a detailed survey of local teenagers as evidence for education reform in her small rural hometown, but she may have less success using the same evidence to argue for similar reforms in a large inner-city community.

College writers also need to consider the fields that they’re working in. In disciplines such as experimental psychology or economics, quantitative data — the sort that can be observed and counted — may be the best evidence. In many historical, literary, or philosophical studies, however, the same kind of data may be less appropriate or persuasive, or even impossible to come by. As you become more familiar with a discipline, you’ll gain a sense of what it takes to support a claim. The following questions will help you understand the rhetorical situation of a particular field:

What kinds of data are preferred as evidence? How are such data gathered and presented?

How are definitions, causal analyses, evaluations, analogies, and examples used as evidence?

How does the field use firsthand and secondhand sources as evidence? What kinds of data are favored?

How are statistics or other numerical information used and presented as evidence? Are tables, charts, or graphs commonly used? How much weight do they carry?

What or who counts as an authority in this field? How are the credentials of authorities established?

What weight do writers in the field give to precedence — that is, to examples of similar actions or decisions made in the past?

Is personal experience allowed as evidence? When?

How are quotations used as part of evidence?

How are still or moving images or sound(s) used as part of evidence, and how closely are they related to the verbal parts of the argument being presented?

As these questions suggest, evidence may not always travel well from one field to another. Nor does it always travel easily from culture to culture. Differing notions of evidence can lead to arguments that go nowhere fast. For instance, when Italian journalist Oriana Fallaci interviewed Ayatollah Khomeini, Iran’s supreme leader, in 1979, she argued in a way that’s common in North American and Western European cultures: she presented claims that she considered to be adequately backed up with facts (“Iran denies freedom to people. . . . Many people have been put in prison and even executed, just for speaking out in opposition”). In response, Khomeini relied on very different kinds of evidence — analogies (“Just as a finger with gangrene should be cut off so that it will not destroy the whole body, so should people who corrupt others be pulled out like weeds so they will not infect the whole field”) and, above all, the authority of the Qur’an. Partly because of these differing beliefs about what counts as evidence, the interview ended unsuccessfully.