Using Data and Evidence from Research Sources

Using Data and Evidence from Research Sources

The evidence you will use in most academic arguments — books, articles, videos, documents, photographs and other images — will likely come from sources you locate in libraries, in databases, or online. How well you can navigate these complex territories will determine the success of many of your academic and professional projects. Research suggests that most students overestimate their ability to manage these tools and, perhaps more important, don’t seek the help they need to find the best materials for their projects. We can’t cover all the nuances of doing academic research here, but we can at least point you in the right directions.

Explore library resources: printed works and databases. Your college library has printed materials (books, periodicals, reference works) as well as terminals that provide access to its electronic catalogs, other libraries’ catalogs via the Internet, and numerous proprietary databases (such as Academic Search Complete, Academic OneFile, JSTOR) not available publicly on the Web. Crucially, libraries also have librarians whose job it is to guide you through these resources, help you identify reputable materials, and show you how to search for materials efficiently. The best way to begin a serious academic argument then is often with a trip to the library or a discussion with your professor or librarian. Also be certain that you know your way around the library. If not, ask the staff there to help you locate the following tools: general and specialized encyclopedias; biographical resources; almanacs, yearbooks, and atlases; book and periodical indexes; specialized indexes and abstracts; the circulation computer or library catalog; special collections; audio, video, and art collections; and the interlibrary loan office.

At the outset of a project, determine what kinds of sources you will need to support your project. (You might also review your assignment to see whether you’re required to consult different kinds of sources.) If you’ll use print sources, find out whether they’re readily available in your library or whether you must make special arrangements (such as an interlibrary loan) to acquire them. For example, your argument for a senior thesis might benefit from material available mostly in old newspapers and magazines: access to them might require time and ingenuity. If you need to locate other nonprint sources (such as audiotapes, videotapes, artwork, or photos), find out where those are kept and whether you need special permission to examine them.

Most academic resources, however, will be on the shelves or available electronically through databases. Here’s when it’s important to understand the distinction between library databases and the Internet/Web. Your library’s computers hold important resources that aren’t on the Web or aren’t available to you except through the library’s system. The most important of these resources is the library’s catalog of its holdings (mostly books), but college libraries also pay to subscribe to scholarly databases — for example, guides to journal and magazine articles, the Academic Search Complete database (which holds the largest collection of multidisciplinary journals), the LexisNexis database of news stories and legal cases, and compilations of statistics — that you can use for free.

You should consult these electronic sources through your college library, perhaps even before turning to the Web. But using these professional databases isn’t always easy or intuitive, even when you can reach them on your own computer. You likely need to learn how to focus and narrow your searches (by date, field, types of material, and so on) so that you don’t generate unmanageable lists of irrelevant items. That’s when librarians or your instructor can help, so ask them for assistance. They expect your questions.

For example, librarians can draw your attention to the distinction between subject headings and keywords. The Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH) are standardized words and phrases that are used to classify the subject matter of books and articles. Library catalogs and databases usually use the LCSH headings to index their contents by author, title, publication date, and subject headings. When you do a subject search of the library’s catalog, you need to use the exact wording of the LCSH headings. On the other hand, searches with keywords use the computer’s ability to look for any term in any field of the electronic record. So keyword searching is less restrictive, but you’ll have to think hard about your search terms to get usable results and to learn how to limit or expand your search.

Determine, too, early on, how current your sources need to be. If you must investigate the latest findings about, say, a new treatment for malaria, check very recent periodicals, medical journals, and the Web. If you want broader, more detailed coverage and background information, look for scholarly books. If your argument deals with a specific time period, newspapers, magazines, and books written during that period may be your best assets.

How many sources should you consult for an academic argument? Expect to look over many more sources than you’ll end up using, and be sure to cover all major perspectives on your subject. Read enough sources to feel comfortable discussing it with someone with more knowledge than you. You don’t have to be an expert, but your readers should sense that you are well informed.

Explore online resources. Chances are your first instinct when you need to find information is to do a quick keyword search on the Web, which in many instances will take you to a source in Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia launched by Jimmy Wales in 2001. For years, many teachers and institutions argued that the information on Wikipedia was suspect and could not be used as a reliable source. Times have changed, however, and many serious research efforts now include a stop at Wikipedia. As always, however, let the buyer beware: you need to verify the credibility of all of your sources! If you intend to support a serious academic argument, remember to approach the Web carefully and professionally.

Like the catalogs and databases in your college library, the Internet offers two ways to search for sources related to an argument — one using subject categories and one using keywords. A subject directory organized by categories (such as you might find at About.com) allows you to choose a broad category like “entertainment” or “science,” and then click on increasingly narrow categories like “movies” or “astronomy,” and then “thrillers” or “the solar system,” until you reach a point where you’re given a list of Web sites or the opportunity to do a keyword search.

With the second kind of Internet search option, a search engine, you start right off with a keyword search — filling in a blank, for example, on Google’s homepage. Because the Internet contains vastly more material than even the largest library catalog or database, exploring it with a search engine requires careful choices and combinations of keywords. For an argument about the fate of the antihero in contemporary films, for example, you might find that film and hero produce far too many possible matches, or hits. You might further narrow the search by adding a third keyword — say, American or current. In doing such searches, you’ll need to observe the search logic that is followed by a particular database. Using and between keywords (movies and heroes) usually indicates that both terms must appear in a file for it to be called up. Using or between keywords usually instructs the computer to locate every file in which either one word or the other shows up, and using not tells the computer to exclude files containing a particular word from the search results (movies not heroes).

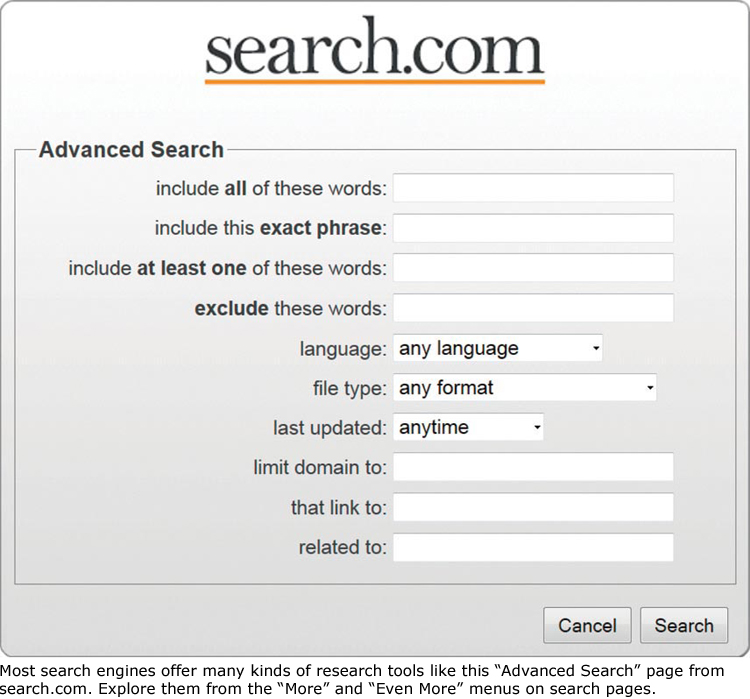

More crucial with a tool like Google is to discover how the resources of the site itself can refine your choice or direct you to works better suited to academic argument. When you search for any term, you can click “Advanced Search” at the bottom of the results page and bring up a full screen of options to narrow your search in important ways.

But that’s not the end of your choices. With an academic argument, you might want to explore your topic in either Google Books or Google Scholar. Both resources send you to the level of materials you might need for a term paper or professional project. And Google offers other options as well: it can direct you to images, photographs, blogs, and so on. The lesson is simple. If your current Web searches typically involve no more than using the first box that a search engine offers, you aren’t close to using all the power available to you. Explore that tool you use all the time and see what it can really do.