Collecting Data on Your Own

Collecting Data on Your Own

Not all your supporting materials for an academic argument must come from print or online sources. You can present research that you have carried out or been closely involved with; this kind of research usually requires that you collect and examine data. Here, we discuss the kinds of firsthand research that student writers do most often.

Perform experiments. Academic arguments can be supported by evidence you gather through experiments. In the sciences, data from experiments conducted under rigorously controlled conditions is highly valued. For other kinds of writing, more informal experiments may be acceptable, especially if they’re intended to provide only part of the support for an argument.

If you want to argue, for instance, that the recipes in Bon Appétit magazine are impossibly tedious to follow and take far more time than the average person wishes to spend preparing food, you might ask five or six people to conduct an experiment — following two recipes from a recent issue and recording and timing every step. The evidence that you gather from this informal experiment could provide some concrete support — by way of specific examples — for your contention.

But such experiments should be taken with a grain of salt (maybe organic in this case). They may not be effective with certain audiences. And if your experiments can easily be attacked as skewed or sloppily done (“The people you asked to make these recipes couldn’t cook a Pop-Tart”), then they may do more harm than good.

Make observations. “What,” you may wonder, “could be easier than observing something?” You just choose a subject, look at it closely, and record what you see and hear. But trained observers say that recording an observation accurately requires intense concentration and mental agility. If observing were easy, all eyewitnesses would provide reliable stories. Yet experience shows that when several people observe the same phenomenon, they generally offer different, sometimes even contradictory, accounts of those observations.

Before you begin an observation yourself, decide exactly what you want to find out, and anticipate what you’re likely to see. Do you want to observe an action that is repeated by many people — perhaps how people behave at the checkout line in a grocery store? Or maybe you want to study a sequence of actions — for instance, the stages involved in student registration, which you want to argue is far too complicated. Or maybe you are motivated to examine the interactions of a notoriously contentious campus group. Once you have a clear sense of what you’ll analyze and what questions you’ll try to answer through the observation, use the following guidelines to achieve the best results:

Make sure that the observation relates directly to your claim.

Brainstorm about what you’re looking for, but don’t be rigidly bound to your expectations.

Develop an appropriate system for collecting data. Consider using a split notebook page or screen: on one side, record the minute details of your observations; on the other, record your thoughts or impressions.

Be aware that the way you record data will affect the outcome, if only in respect to what you decide to include in your observational notes and what you leave out.

Record the precise date, time, and place of the observation(s).

You may be asked to prepare systematic observations in various science courses, including anthropology or psychology, where you would follow a methodology and receive precise directions. But observation can play a role in other kinds of arguments and use various media: a photo essay, for example, might serve as an academic argument in some situations.

Conduct interviews. Some evidence is best obtained through direct interviews. If you can talk with an expert — in person, on the phone, or online — you might obtain information you couldn’t have gotten through any other type of research. In addition to an expert opinion, you might ask for firsthand accounts, biographical information, or suggestions of other places to look or other people to consult. The following guidelines will help you conduct effective interviews:

Determine the exact purpose of the interview, and be sure it’s directly related to your claim.

Set up the interview well in advance. Specify how long it’ll take, and if you wish to record the session, ask permission to do so.

Prepare a written list of both factual and open-ended questions. (Brainstorming with friends can help you come up with good questions.) Leave plenty of space for notes after each question. If the interview proceeds in a direction that you hadn’t expected but that seems promising, don’t feel that you have to cover every one of your questions.

Record the subject’s full name and title, as well as the date, time, and place of the interview.

Be sure to thank those people whom you interview, either in person or with a follow-up letter or email message.

A serious interview can be eye-opening when the questions get a subject to reveal important experiences or demonstrate his or her knowledge or wisdom.

In his article “Immigrants Who Speak Indigenous Languages Encounter Isolation,” Kirk Semple draws on several different surveys to provide the necessary factual grounding for his argument.

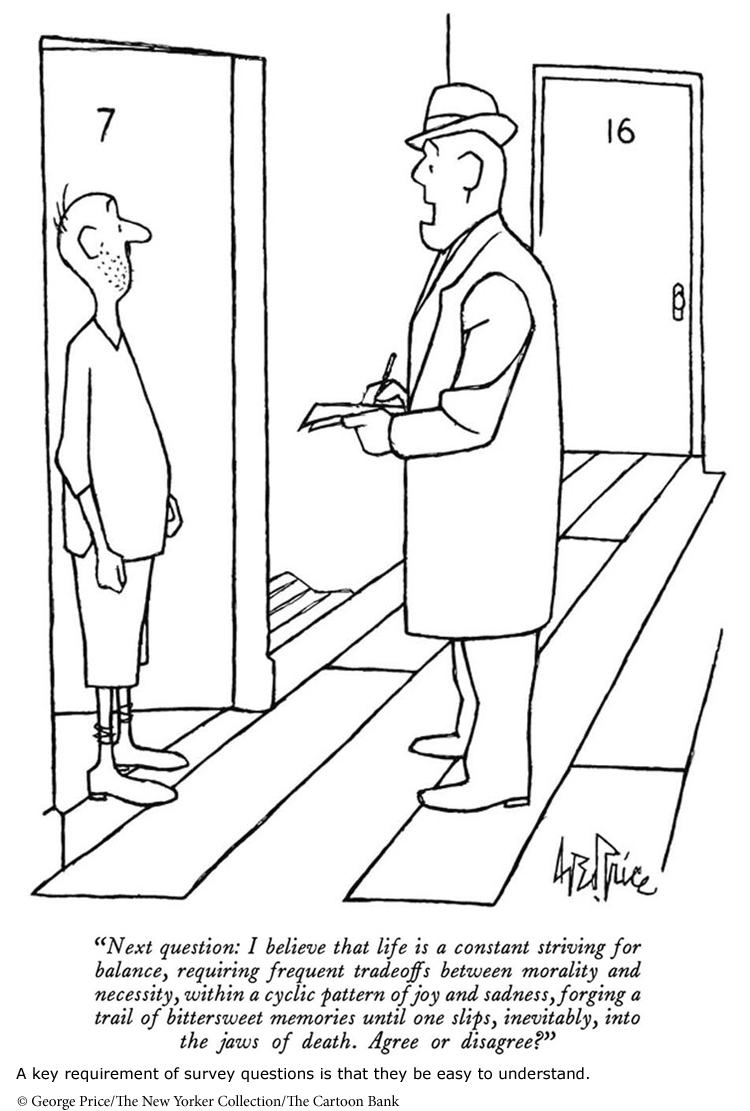

Use questionnaires to conduct surveys. Surveys usually require the use of questionnaires. Questions should be clear, easy to understand, and designed so that respondents’ answers can be easily analyzed. Questions that ask respondents to say “yes” or “no” or to rank items on a scale (1 to 5, for example, or “most helpful” to “least helpful”) are particularly easy to tabulate. Because tabulation can take time and effort, limit the number of questions you ask. Note also that people often resent being asked to answer more than about twenty questions, especially online.

Here are some other guidelines to help you prepare for and carry out a survey:

Ask your instructor if your college or university requires that you get approval from the local Institutional Review Board (IRB) to conduct survey research. Many schools waive this requirement if students are doing such research as part of a required course, but you should check to make sure. Securing IRB permission usually requires filling out a series of online forms, submitting all of your questions for approval, and asking those you are surveying to sign a consent form saying they agree to participate in the research.

Write out your purpose in conducting the survey, and make sure that its results will be directly related to your purpose.

Brainstorm potential questions to include in the survey, and ask how each relates to your purpose and claim.

Figure out how many people you want to contact, what the demographics of your sample should be (for example, men in their twenties or an equal number of men and women), and how you plan to reach these people.

Draft questions that are as free of bias as possible, making sure that each calls for a short, specific answer.

Think about possible ways that respondents could misunderstand you or your questions, and revise with these points in mind.

Test the questions on several people, and revise those questions that are ambiguous, hard to answer, or too time-consuming to answer.

If your questionnaire is to be sent by mail or email or posted on the Web, draft a cover letter explaining your purpose and giving a clear deadline. For mail, provide an addressed, stamped return envelope.

On the final draft of the questionnaire, leave plenty of space for answers.

Proofread the final draft carefully. Typos will make a bad impression on those whose help you’re seeking.

After you’ve done your tabulations, set out your findings in clear and easily readable form, using a chart or spreadsheet if possible.

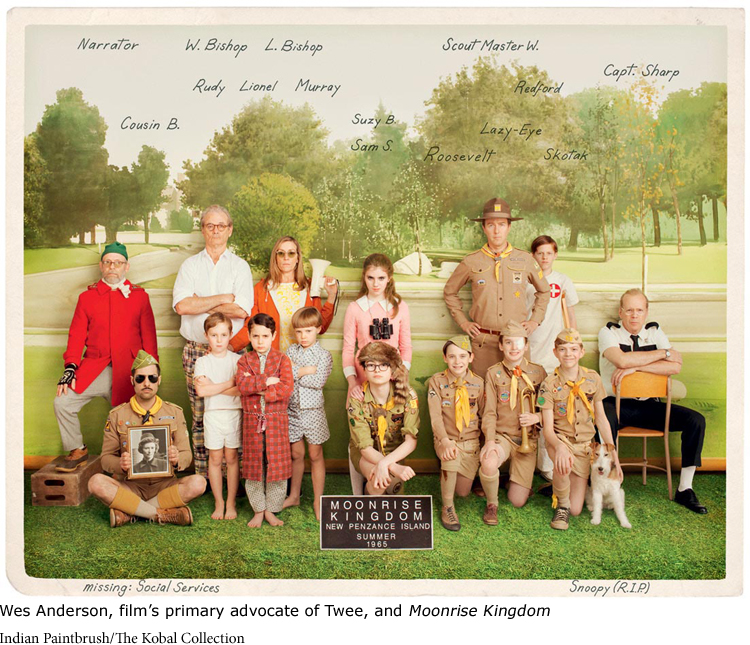

Draw upon personal experience. Personal experience can serve as powerful evidence when it’s appropriate to the subject, to your purpose, and to the audience. If it’s your only evidence, however, personal experience usually won’t be sufficient to carry the argument. Your experiences may be regarded as merely “anecdotal,” which is to say possibly exceptional, unrepresentative, or even unreliable. Nevertheless, personal experience can be effective for drawing in listeners or readers, as James Parker does in the following example. His full article goes on to argue that — in spite of his personal experience with it — the “Twee revolution” has some good things going for it, including an “actual moral application”:

Eight years ago or so, the alternative paper I was working for sent me out to review a couple of folk-noise-psych-indie-beardie-weirdie bands. I had a dreadful night. The bands were bad enough — “fumbling,” I scratched in my notebook, “infantile” — but what really did me in was the audience. Instead of baying for the blood of these lightweights . . . the gathered young people — behatted, bebearded, besmiling — obliged them with patters of validating applause. I had seen it before, this fond curiosity, this acclamation of the undercooked, but never so much of it in one place: the whole event seemed to exult in its own half-bakedness. Be as crap as you like was the message to the performers. The crapper, the better. We’re here for you. I tottered home, wrote a homicidally nasty nervous breakdown of a review, and decided I should take myself out of circulation for a while. No more live reviews until I calmed down. A wave of Twee — as I now realize — had just broken over my head.

— James Parker, The Atlantic, July/August 2014, p. 36

RESPOND •

The following is a list of general topic ideas from the Yahoo! Directory’s “Issues and Causes” page. Narrow one or two of the items down to a more specific subject by using research tools in the library or online such as scholarly books, journal articles, encyclopedias, magazine pieces, and/or informational Web sites. Be prepared to explain how the particular research resources influenced your choice of a more specific subject within the general subject area. Also consider what you might have to do to turn your specific subject into a full-blown topic proposal for a research paper assignment.

Age discrimination Poverty Child soldiers Racial profiling Climate change Solar power Corporal punishment Sustainable agriculture Drinking age Tax reform Educational equity Urban sprawl Immigration reform Video games Media ethics and accountability Violence in the NFL Military use of drones Whistleblowing Pornography Zoos Go to your library’s online catalog page and locate its list of research databases. You may find them presented in various ways: by subject, by field, by academic major, by type — even alphabetically. Try to identify three or four databases that might be helpful to you either generally in college or when working on a specific project, perhaps one you identified in the previous exercise. Then explore the library catalog to see how much you can learn about each of these resources: What fields do they report on? What kinds of data do they offer? How do they present the content of their materials (by abstract, by full text)? What years do they cover? What search strategies do they support (keyword, advanced search)? To find such information, you might look for a help menu or an “About” link on the catalog or database homepages. Write a one-paragraph description of each database you explore and, if possible, share your findings via a class discussion board, blog, or wiki.

What counts as evidence depends in large part on the rhetorical situation. One audience might find personal testimony compelling in a given case, whereas another might require data that only experimental studies can provide. Imagine that you want to argue that advertisements should not include demeaning representations of chimpanzees and that the use of primates in advertising should be banned. You’re encouraged to find out that a number of companies such as Honda and Puma have already agreed to such a ban, so you decide to present your argument to other companies’ CEOs and advertising officials. What kind of evidence would be most compelling to this group? How would you rethink your use of evidence if you were writing for the campus newspaper, for middle-schoolers, or for animal-rights group members? What can you learn about what sort of evidence each of these groups might value — and why?

Finding evidence for an argument is often a discovery process. Sometimes you’re concerned not only with digging up support for an already established claim but also with creating and revising tentative claims. Surveys and interviews can help you figure out what to argue, as well as provide evidence for a claim.

Interview a classmate with the goal of writing a brief proposal argument about the career that he/she should pursue. The claim should be something like My classmate should be doing X five years from now. Limit yourself to ten questions. Write them ahead of time, and don’t deviate from them. Record the results of the interview (written notes are fine; you don’t need to tape the interview). Then interview another classmate with the same goal in mind. Ask the same first question, but this time let the answer dictate the next nine questions. You still get only ten questions.

Which interview gave you more information? Which one helped you learn more about your classmate’s goals? Which one better helped you develop claims about his/her future?