Assessing Print Sources

Assessing Print Sources

Since you want information to be reliable and persuasive, it pays to evaluate each potential source thoroughly. The following principles can help you evaluate print sources:

Relevance. Begin by asking what a particular source will add to your argument and how closely the source is related to your argumentative claim. For a book, the table of contents and the index may help you decide. For an article, look for an abstract that summarizes its content. If you can’t think of a good reason for using the source, set it aside. You can almost certainly find something better.

Credentials of the author. Sometimes the author’s credentials are set forth in an article, in a book, or on a Web site, so be sure to look for them. Is the author an expert on the topic? To find out, you can gather information about the person on the Internet using a search engine like Yahoo! or Ask.com. Another way to learn about the credibility of an author is to search Google Groups for postings that mention the author or to check the Citation Index to find out how others refer to this author. If you see your source cited by other sources you’re using, look at how they cite it and what they say about it, which could provide clues to the author’s credibility.

Stance of the author. What’s the author’s position on the issue(s) involved, and how does this stance influence the information in the source? Does the author’s stance support or challenge your own views?

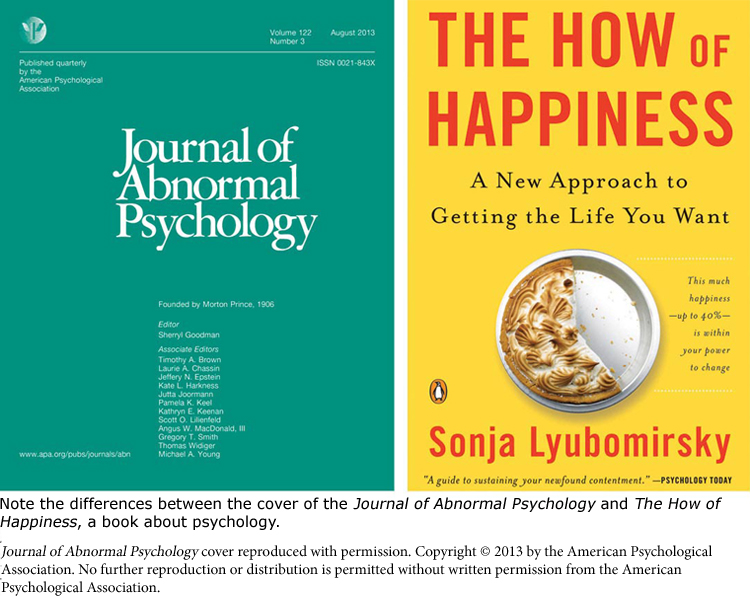

Credentials of the publisher or sponsor. If your source is from a newspaper, is it a major one (such as the Wall Street Journal or the Washington Post) that has historical credentials in reporting, or is it a tabloid? Is it a popular magazine like O: The Oprah Magazine or a journal sponsored by a professional group, such as the Journal of the American Medical Association? If your source is a book, is the publisher one you recognize or that has its own Web site? When you don’t know the reputation of a source, ask several people with more expertise: a librarian, an instructor, or a professional in the field.

Stance of the publisher or sponsor. Sometimes this stance will be obvious: a magazine called Save the Planet! will take a pro-environmental position, whereas one called America First! will probably take a conservative stance. But other times, you need to read carefully between the lines to identify particular positions and see how the stance affects the message the source presents. Start by asking what the source’s goals are: what does the publisher or sponsoring group want to make happen?

Page 431Currency. Check the date of publication of every book and article. Recent sources are often more useful than older ones, particularly in the sciences. However, in some fields (such as history and literature), the most authoritative works may well be the older ones.

Accuracy. Check to see whether the author cites any sources for the information or opinions in the article and, if so, how credible and current they are.

Level of specialization. General sources can be helpful as you begin your research, but later in the project you may need the authority or currency of more specialized sources. Keep in mind that highly specialized works on your topic may be difficult for your audience to understand.

Audience. Was the source written for a general readership? For specialists? For advocates or opponents?

Length. Is the source long enough to provide adequate details in support of your claim?

Availability. Do you have access to the source? If it isn’t readily accessible, your time might be better spent looking elsewhere.

Omissions. What’s missing or omitted from the source? Might such exclusions affect whether or how you can use the source as evidence?

Consider the differences in a publisher’s credentials by comparing Daniel J. Solove’s book excerpt, which was published by Yale University Press, and Amy Zimmerman’s engaging article from the Daily Beast. Do your expectations differ?