Charles A. Riley II, Disability and the Media: Prescriptions for Change

Charles A. Riley II is a professor of journalism at Baruch College, part of the City University of New York. He also served as editor in chief of WE, a now-defunct national bimonthly magazine that focused on disability issues. During his career, he has received several awards for his writing on issues relating to disability. (Riley is able-bodied, a fact that he believes has important consequences for his writing on these issues.) Among his books are Aristocracy and the Modern Imagination (1980); Disability and Business: Best Practices and Strategies for Inclusion (1980); Color Codes: Modern Theories of Color in Philosophy, Painting and Architecture, Literature, Music, and Psychology (1995); Small Business, Big Politics: What Entrepreneurs Need to Know to Use Their Growing Political Power (1996); and The Jazz Age in France (2004). The selections featured here come from Disability and the Media: Prescriptions for Change (2005). These selections include the opening pages of Riley’s preface as well as an appendix created by the National Center on Disability and Journalism in 2002 that offers guidelines for portraying people with disabilities in the media. As you read, note ways in which Riley marshals evidence to demonstrate a need for change and how the appendix constitutes a set of proposals to create that change.

527

Disability and the Media: Prescriptions for Change

CHARLES A. RILEY II

Every time Aimee Mullins sees her name in the papers she braces herself for some predictable version of the same headline followed by the same old story. Paralympian, actress, and fashion model, Mullins is a bilateral, below-the-knee amputee, who sprints a hundred meters in less than sixteen seconds on a set of running prostheses called Cheetahs because they were fashioned after the leg form of the world’s fastest animal. First, there are the headlines: “Overcoming All Hurdles” (she is not a hurdler, although she is a long jumper) or “Running Her Own Race,” “Nothing Stops Her,” or the dreaded overused “Profile in Courage.” Then come the clichés and stock scenes, from the prosthetist’s office to the winner’s podium. Many of the articles dwell on her success as the triumph of biomechanics, a “miracle of modern medicine,” turning her fairy tale into a Coppélia narrative (or a Six Million Dollar Woman movie sequel). From the local paper where she grew up (Allentown, Pennsylvania), to national exposure in Esquire and People and guest spots on Oprah, Mullins’s “inspiring” saga is recycled almost verbatim by well-meaning journalists for audiences who never seem to get enough of its feel-good message even if they never actually find out who Mullins is.

528

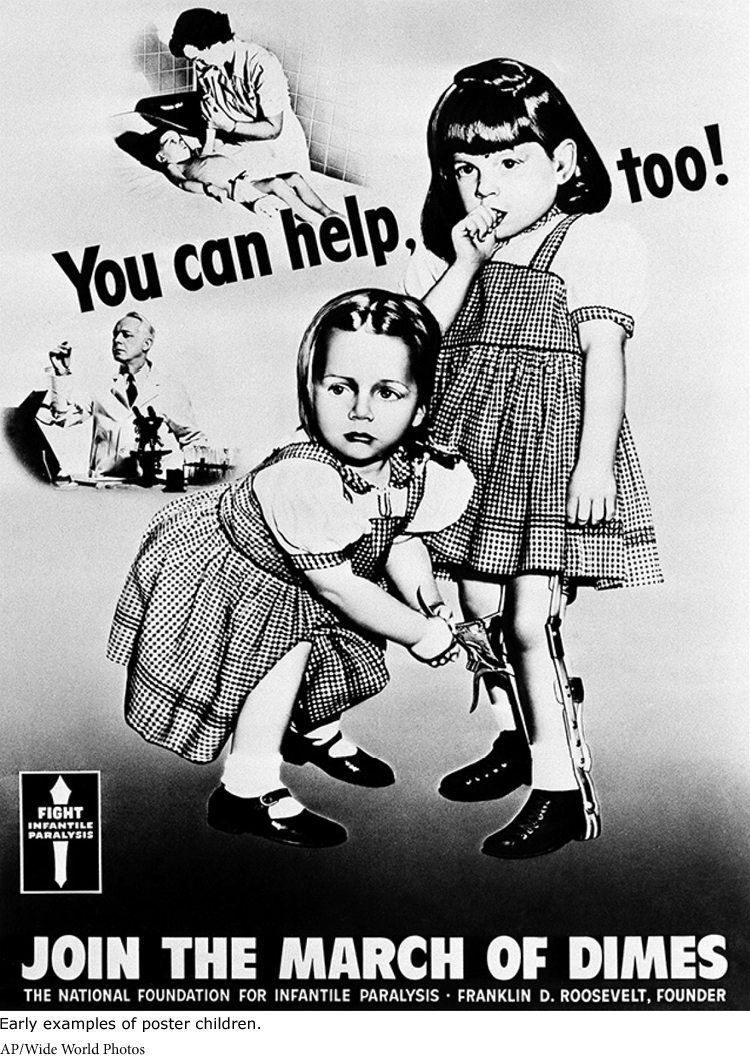

This is the patronizing, trivializing, and marginalizing ur-narrative of disability in the media today. The mainstream press finds it irresistible, but this steady diet of sugar has its dangers. The cliché has excluded the mature, fully realized coverage that people with disabilities have long deserved. For Mullins, it has translated into well over her Warholian fifteen minutes of fame, bringing her the financial rewards of sponsorships, motivational speaking gigs, and modeling contracts at the expense of being turned into a latter-day poster child. Stories about her rarely get around to mentioning that she was a Pentagon intern while making the dean’s list as an academic star in history and diplomacy at Georgetown, or that she is one of the actresses in Matthew Barney’s avant-garde Cremaster film series.

Before he offers his proposal, Riley first explains how stereotyping causes problems for the disabled. For more on causal arguments, see Chapter 11.

Mullins is not the only celebrity with a disability to be steamrolled out of three-dimensional humanity into allegorical flatness. All the branches of the media considered here, from print to television, radio and the movies (including advertisements) to multimedia and the Internet, are guilty of the same distillation of stories to meet their own, usually fiscal, ends. For example, even though her autobiography is remarkably ahead of its time in its anticipation of disability culture, by the time Helen Keller had been sweetened for movie audiences in Patty Duke’s version of her life, little was left out of the fiery trailblazer. In much the same way, Christopher Reeve and Michael J. Fox have been pigeonholed by print and television hagiographers as lab experiments and tragic heroes. Packaged to raise philanthropic or advertising dollars, they perform roles no less constrained than the pretty-boy parts they played on screen earlier in their lives.

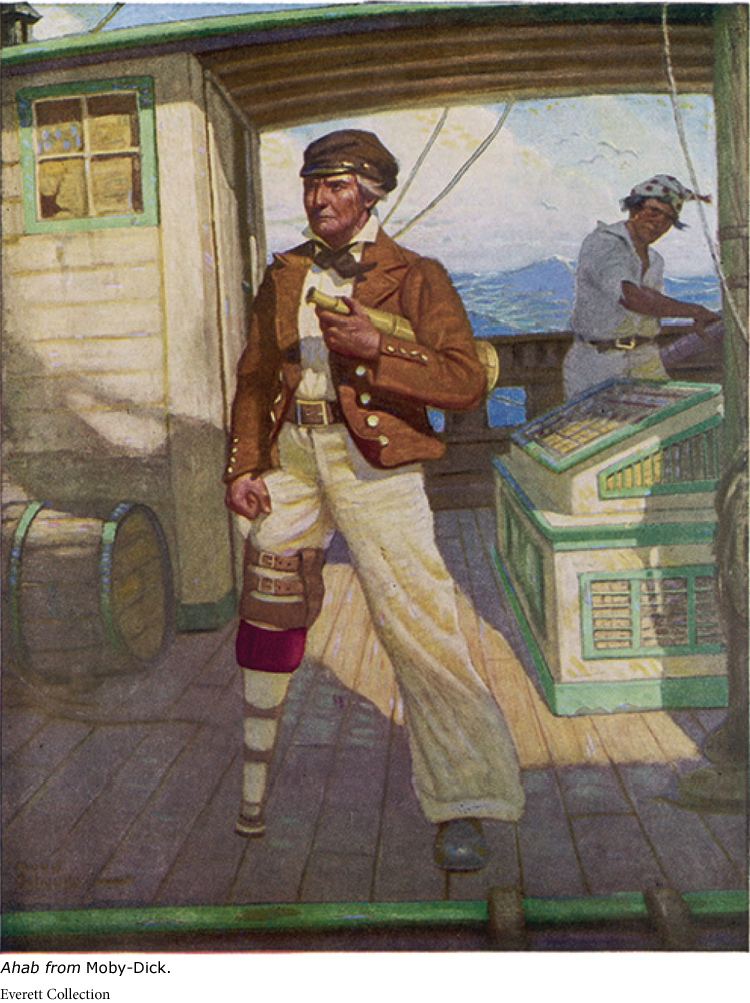

What is wrong with this picture? By jamming Mullins and the others into prefabricated stories — the supercrip, the medical miracle, the object of pity — writers and producers have outfitted them with the narrative equivalent of an ill-fitting set of prostheses. Each of these archetypal narratives has its way of reaching mass audiences, selling products (including magazines and movie tickets), and financially rewarding both the media outlet and the featured subject. In some ways, as optimists point out, this represents an improvement. We have had millennia of fiction and nonfiction depicting angry people with disabilities as villains, from Oedipus to Ahab to Dr. Strangelove. The vestigial traces of that syndrome still occasionally recur, although with far less frequency, in current movies or television series and in journalists’ fixation on the mental instability of violent criminals. However, today’s storytellers, including those in the disability media, are more likely to make people with disabilities into “heroes of assimilation,” to borrow a phrase from Erving Goffman’s seminal work on disability, Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity.

530

5 As Goffman knew too well, just as the stigmatization of the villain had its dilatory effects on societal attitudes, so too does relentless hagiography, particularly by transforming individuals into symbols and by playing on an audience’s sympathy and sense of superiority. Those who labor in the field of disability studies point out that disability culture and its unique strengths are absent from this story of normalization. Others would simply note that the individual is lost in the fable, an all-American morality tale that strikes one of the most resonant chords in the repertoire: redemption. Like the deathless Horatio Alger tale, the story of the hero of assimilation emphasizes many of the deepest values and beliefs of the Puritan tradition, especially the notion that suffering makes us stronger and better. An able-bodied person falls from grace (often literally falling or crashing, as in the case of many spinal cord injuries), progresses through the shadows of rehabilitation and depression, and by force of willpower along with religious belief pulls through to attain a quality of life that is less disabled, more normal, basking in the glow of recognition for beating the odds.

531

This pervasive narrative can be found in print, on television, in movies, in advertisements, and on the Web. Its corrosive effect on understanding and attitudes is as yet unnoticed. It is impossible to know the full degree of damage wreaked by the demeaning and wildly inaccurate portrayal of people with disabilities, nor is it altogether clear whether much current progress is being made. Painful as it is for me as an advocate to report the bad news, I cannot help but point out that the “movement” has slowed to a crawl in terms of political and economic advancement for 54 million Americans. The stasis that threatens is at least partly to be blamed on a reassuring, recurring image projected by the media that numbs nondisabled readers and viewers into thinking that all is well.

This study aims to expose the extent of the problem while pinpointing how writers, editors, photographers, filmmakers, advertisers, and the executives who give them their marching orders go wrong, or occasionally get it right. Through a close analysis of the technical means of representation, in conjunction with the commentary of leading voices in the disability community, I hope to guide future coverage to a more fair and accurate way of putting the disability story on screen or paper. Far from another stab at the political correctness target, the aim of this content analysis of journalism, film, advertising, and Web publishing is to cut through the accumulated clichés and condescension to find an adequate vocabulary that will finally represent the disability community in all its vibrant and fascinating diversity. Nothing like that will ever happen if the press and advertisers continue to think, write, and design as they have in the past.

APPENDIX A

GUIDELINES FOR PORTRAYING PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES IN THE MEDIA

Fear of the unknown. Inadequate experience. Incorrect or distorted information. Lack of knowledge. These shape some of the attitudinal barriers that people with disabilities face as they become involved in their communities.

People working in the media exert a powerful influence over the way people with disabilities are perceived. It’s important to the 54 million Americans with disabilities that they be portrayed realistically and that their disabilities are explained accurately.

Awareness is the first step toward change.

532

TIPS FOR REPORTING ON PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES

When referring to individuals with disabilities use “disability,” not “handicapped.”

Emphasize the person, not the disability or condition. Use “people with disabilities” rather than “disabled persons,” and “people with epilepsy” rather than “epileptics.”

Omit mention of an individual’s disability unless it is pertinent to the story.

Depict the typical achiever with a disability, not just the super-achiever.

Choose words that are accurate descriptions and have non-judgmental connotations.

People with disabilities live everyday lives and should be portrayed as contributing members of the community. These portrayals should:

Depict people with disabilities experiencing the same pain/pleasure that others derive from everyday life, e.g., work, parenting, education, sports and community involvement.

Feature a variety of people with disabilities when possible, not just someone easily recognized by the general public.

Depict employees/employers with disabilities working together.

Ask people with disabilities to provide correct information and assistance to avoid stereotypes in the media.

Portray people with disabilities as people, with both strengths and weaknesses.

APPROPRIATE WORDS WHEN PORTRAYING PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES

Never Use

victim — use: person who has/experienced/with.

[the] cripple[d] — use: person with a disability.

afflicted by/with — use: person has.

invalid — use: a person with a disability.

normal — most people, including people with disabilities, think they are.

patient — connotes sickness. Use: person with a disability.

Avoid Using

wheelchair bound/confined — use: uses a wheelchair or wheelchair user.

homebound employment — use: employed in the home.

Use with Care

courageous, brave, inspirational and similar words routinely used to describe persons with disabilities. Adaption to a disability does not necessarily mean someone acquires these traits.

533

INTERVIEWING PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES

When interviewing a person with a disability, relax! Conduct your interview as you would with anyone. Be clear and candid in your questioning and ask for clarification of terms or issues when necessary. Be upfront about deadlines, the focus of your story, and when and where it will appear.

Interviewing Etiquette

Shake hands when introduced to someone with a disability. People with limited hand use or artificial limbs do shake hands.

Speak directly to people with disabilities, not through their companions.

Don’t be embarrassed using such phrases as “See you soon,” “Walk this way” or “Got to run.” These are common expressions, and are unlikely to offend.

If you offer to help, wait until the offer is accepted.

Consider the needs of people with disabilities when planning events.

Conduct interviews in a manner that emphasizes abilities, achievements and individual qualities.

Don’t emphasize differences by putting people with disabilities on a pedestal.

This appendix offers a set of clear guidelines but sometimes does not explain the reasoning behind particular guidelines. Practice identifying the warrants, as described in Chapter 7, that lie behind these claims.

When Interviewing People with Hearing Disabilities

Attract the person’s attention by tapping on his or her shoulder or waving.

If you are interviewing someone with a partial hearing loss, ask where it would be most comfortable for you to sit.

If the person is lip-reading, look directly at him/her and speak slowly and clearly. Do not exaggerate lip movements or shout. Do speak expressively, as facial expressions, gestures and body movements will help him/her understand you.

Position yourself facing the light source and keep hands and food away from your mouth when speaking.

534

When Interviewing People with Vision Disabilities

Always identify yourself and anyone else who might be present.

When offering a handshake, say, “Shall we shake hands?”

When offering seating, place the person’s hand on the back or arm of the seat.

Let the person know if you move or need to end the conversation.

When Interviewing People with Speech Disabilities

Ask short questions that require short answers when possible.

Do not feign understanding. Try rephrasing your questions, if necessary.

When Interviewing People Using a Wheelchair or Crutches

Do not lean on a person’s wheelchair. The chair is part of his/her body space.

Sit or kneel to place yourself at eye level with the person you are interviewing.

Make sure the interview site is accessible. Check for:

Reserved parking for people with disabilities

A ramp or step-free entrance

Accessible restrooms

An elevator if the interview is not on the first floor

Water fountains and telephones low enough for wheelchair use

Be sure to notify the interviewee if there are problems with the location. Discuss what to do and make alternate plans.

WRITING ABOUT DISABILITY

One of the first and most significant steps to changing negative stereotypes and attitudes toward people with disabilities begins when we rethink the way written and spoken images are used to portray people with disabilities. The following is a brief, but important, list of suggestions for portraying people with disabilities in the media.

People with disabilities are not “handicapped,” unless there are physical or attitudinal barriers that make it difficult for them to participate in everyday activities. An office building with steps and no entry ramp creates a “handicapping” barrier for people who use wheelchairs. In the same way, a hotel that does not have a TTY/telephone (teletypewriter) creates a barrier for someone who is hearing disabled. It is important to focus on the person, not necessarily the disability. In writing, name the person first and then, if necessary, explain his or her disability. The same rule applies when speaking. Don’t focus on someone’s disability unless it’s crucial to the point being made.

535

In long, written materials, when many references have been made to persons with disabilities or someone who is disabled, it is acceptable for later references to refer to “disabled persons” or “disabled individuals.”

15 Because a person is not a condition or a disease, avoid referring to someone with a disability by his or her disability alone. For example, don’t say someone is a “post-polio” or a “C.P.” or an “epileptic.” Refer instead to someone who has post-polio syndrome, or has cerebral palsy, or has epilepsy.

Don’t use “disabled” as a noun because it implies a state of separateness. “The disabled” are not a group apart from the rest of society. When writing or speaking about people with disabilities, choose descriptive words and portray people in a positive light.

Avoid words with negative connotations:

Avoid calling someone a “victim.”

Avoid referring to people with disabilities as “cripples” or “crippled.” This is negative and demeaning language.

Don’t write or say that someone is “afflicted.”

Avoid the word “invalid” as it means, quite literally, “not valid.”

Write or speak about people who use wheelchairs. Wheelchair users are not “wheelchair-bound.”

Refer to people who are not disabled as “non-disabled” or “able-bodied.” When you call non-disabled people “normal,” the implication is that people with disabilities are not normal.

Someone who is disabled is only a patient to his or her physician or in a reference to medical treatment.

Avoid cliches. Don’t use “unfortunate,” “pitiful,” “poor,” “dumb,” “crip,” “deformed,” “retard,” “blind as a bat” or other patronizing and demeaning words.

In the same vein, don’t glamorize or make heroes of people with disabilities simply because they have adapted to their disabilities.

Your concerted efforts to use positive, non-judgmental respectful language when referring to people with disabilities in writing and in everyday speaking can go a long way toward helping to change negative stereotypes.

These guidelines are used by permission. Copyright © 2002, National Center on Disability and Journalism.

RESPOND •

536

In what ways does Riley contend that the media and popular culture wrongly stereotype people with disabilities? What negative consequences follow from this stereotyping for such people? For those who do not have disabilities? Why?

How convincingly has Riley defined a problem or need, which is the first step in a proposal argument? (For a discussion of proposal arguments, see Chapter 12.)

What is your response to “Appendix A: Guidelines for Portraying People with Disabilities in the Media”? Are you familiar with the practices that these guidelines seek to prevent? Do you find the guidelines useful or necessary? Why or why not? What justification might be offered for why specific guidelines are important? (Here, you will want to choose three or four of the guidelines and make explicit the arguments in support of each of them.)

Look for some specific representations of people with disabilities in current media and popular culture — in advertisements, television programs, or movies. To what extent do these representations perpetuate the stereotypes that Riley discusses, “the supercrip, the medical miracle, the object of pity” (paragraph 4)? Write an argument of fact in which you present your findings. (For a discussion of arguments of fact, see Chapter 8.) If you do not find representations of people with disabilities in various media or in popular culture, that absence is significant and merits discussion and analysis.

Write an evaluative essay in which you assess the value of these guidelines. In other words, if the media follow these guidelines, what will the consequences be for the media? For society at large? To what extent will following these guidelines likely influence negative stereotypes about people with disabilities? (For a discussion of evaluative arguments, see Chapter 10.)

Click to navigate to this activity.