Christian Weisser, Sustainability

We open this chapter, which is devoted to food, with a reading about sustainability by Christian R. Weisser, an associate professor of English at Penn State Berks. Two of Weisser’s interests are environmental rhetoric and what we might term public rhetoric, moving rhetoric beyond classrooms into the world. He seeks to do just that in this selection, which is adapted from his introduction to Sustainability: A Bedford Spotlight Reader (2014). As Weisser notes, although the term was coined in Germany in 1804, discussions and debates about sustainability have grown exponentially in recent decades, representing one of the most significant discourses that define our era. And as you’ll see in reading the selections in this chapter, discussions about food quickly turn to questions of sustainability, whether the issue is eating locally or food insecurity in developing nations. Thus, sustainability serves as an appropriate framework for thinking about the complexity of these issues. As you read this selection, pay special attention to the ways that Weisser defines sustainability and how he justifies its importance.

Sustainability

CHRISTIAN R. WEISSER

WHAT IS SUSTAINABILITY?

You’ve probably heard the term “sustainability” in some context. It is likely that you’ve used some product or service that was labeled as sustainable, or perhaps you are aware of a campus or civic organization that focuses on sustainability. You may even recognize that sustainability has to do with preserving or maintaining resources; we often associate sustainability with things like recycling, using renewable energy sources like solar and wind power, and preserving natural spaces like rain forests and coral reefs. However, unless you have an inherent interest in sustainability, you probably haven’t thought much about what the term actually means. In fact, many people do not have a clear sense of what sustainability is or why it is so important. The following description will provide a starting point for your investigations of sustainability.

Simply put, sustainability is the capacity to endure or continue. If a thing or an activity is sustainable, it can be reused, recycled, or repeated in some way because it has not exhausted all of the resources or energy required to create it. Sustainability can be broadly defined as the ability of something to maintain itself, and biological systems such as wetlands or forests are good examples of sustainability because they remain diverse and productive over long periods of time. Seen in this way, sustainability has to do with preserving resources and energy over the long term rather than exhausting them quickly to meet short-term needs or goals.

Many current discussions about sustainability focus on the ways in which human activity — and human life itself — can be maintained in the future without exhausting all of our current resources. Historically, there has been a close correlation between the growth of human society and environmental degradation — as communities grow, the environment often declines. Sustainability seeks new ways of addressing that relationship, which would allow human societies and economies to grow without destroying or over-exploiting the environment or ecosystems in which those societies exist. The most widely quoted definition of sustainability comes from the Brundtland Report by the World Commission on Environment and Development in 1987, which defined sustainability as meeting “the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”

In other words, sustainability is based on the idea that human society should use industrial and biological processes that can be sustained indefinitely or at least for a very long time and that those processes should be cyclical rather than linear. The idea of “waste” is important here; a truly sustainable civilization would have little or no waste, and each turn of the industrial cycle would become the material for the next cycle. A basic premise of sustainability, then, is that many of our current practices are unsustainable and that human society will need to change to ensure that people in the future live in a world that is virtually no worse than the one we inherited.

5 As a quick example of sustainability, think about aluminum soda cans. In the past, many soda cans were used and thrown away without a whole lot of thought. Their creation, use, and disposal was a linear process, and lots of soda cans wound up in landfills and trash dumps. The practice of throwing them away was unsustainable because ready sources of aluminum are limited and landfills and trash dumps were filling with wasted cans. Consequently, governments and private corporations began to recycle aluminum soda cans, and today more than 100,000 soda cans are recycled each minute in the United States. In fact, today’s typical used soda can returns as a new can in just sixty days. A billion-dollar recycling industry has emerged, creating jobs and profits for the workers and businesses employed in that enterprise, while at the same time using limited resources more thoughtfully and reducing the impact on the environment. The process has become cyclical, resulting in the continued use of materials, rather than linear, in which a soda can is used once and then becomes waste. Many questions remain about the actual benefits of recycling, but most people agree that recycling is a more-sustainable solution than pitching our used soda cans into the trash.

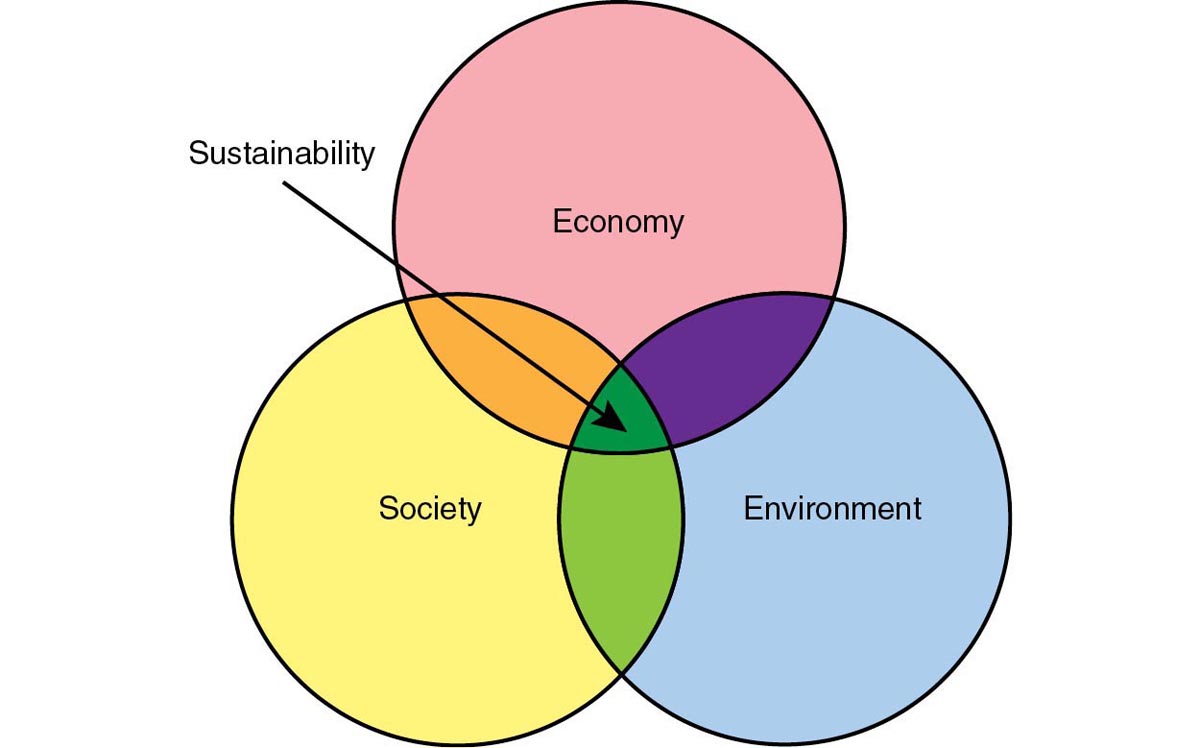

But sustainability is about more than just the economic benefits of recycling materials and resources. Although the economic factors are important, sustainability also accounts for the social and environmental consequences of human activity. This concept, referred to as the “three pillars of sustainability,” asserts that true sustainability depends on three interlocking factors: social equity, environmental preservation, and economic viability. Some describe this three-part model as People, Planet, Profit. First, people and communities must be treated fairly and equally — particularly with regard to eradicating global poverty and ending the environmental exploitation of poor countries and communities. Second, sustainable human activities must protect the earth’s environment. And, third, sustainability must be economically feasible — human development depends on the long-term production, use, and management of resources as part of a global economy. Only when all three of these pillars are incorporated can an activity or enterprise be described as sustainable. The following diagram illustrates the ways in which these three components intersect:

As this model should make clear, sustainability must consider the environment, society, and the economy to be successful. In fact, the earliest definitions of sustainability account for this relationship. The term sustainability first appeared in forestry studies in Germany in the 1800s, when forest overseers began to manage timber harvesting for continued use as a resource. In 1804, German forestry researcher Georg Hartig described sustainability as “utilizing forests to the greatest possible extent, but still in a way that future generations will have as much benefit as the living generation” (Schmutzenhofer 1992).1 Although our current definitions are quite different and much expanded from Hartig’s, sustainability still accounts for the need to preserve natural spaces, to use resources wisely, and to maintain them in an equitable manner for all human beings, both now and in the future.

Our current definitions of sustainability — particularly in the United States — are deeply influenced by our historical and cultural relationship with nature. Many American thinkers, writers, and philosophers have focused on the value of natural spaces, and they have contributed to our collective understanding about the relationship between humans and the environment. Their ideas contributed to the environmentalist movement that emerged in the second half of the twentieth century. Environmentalism advocates for the protection and restoration of nature, and grassroots environmental organizations lobby for changes in public policy and individual behavior to preserve the natural world. The Sierra Club, for example, is one of the oldest, largest, and most influential environmental organizations in the United States.

Environmentalism and sustainability have a lot in common. In fact, some people think that our current conversations about sustainability are the next development or evolution of environmentalism. However, earlier environmental debates often pitted the environment against the economy — nature vs. jobs — and this dichotomy created a rift between those supporting one side of the debate against the other. The battle between the “tree huggers” and the “greedy industrialists” left a lot of people out of the conversation. Many current discussions involving sustainability hope to bridge that gap by looking for possibilities that balance a full range of perspectives and interests — a win-win solution rather than a win-lose scenario. Sustainability encourages and provides incentives for change rather than mandating change, and the three pillars of sustainability emphasize this incorporation. Many sustainability advocates imagine new technologies as mechanisms to protect the planet while also creating economic opportunities and growth; other sustainable approaches simply endorse new ways of thinking and acting. In essence, sustainability looks for coordinated innovation to create a future that merges environmental, economic, and social interests rather than setting them in opposition.

WHY CONSIDER SUSTAINABILITY?

SUSTAINABILITY IS IMPORTANT

10 In some ways, sustainability is the most important conversation taking place in our society today. The earth is our home, and it provides all of the things we need for our survival and nourishment. However, that home has limited resources, and our collective future will depend on the successful management and use of those resources. We are living in a critical time, in which global supply of natural resources and ecosystem services is declining dramatically, while demand for these resources is escalating. From pollution, to resource depletion, to loss of biodiversity, to climate change, a growing human footprint is evident. This is not sustainable. We need to act differently if the world and its human and nonhuman inhabitants are to thrive in the future. Sustainability is about how we can preserve the earth and ensure the continued survival and nourishment of future generations. You and everyone you know will be affected in some way by the choices our society makes in the future regarding the earth and its resources. In fact, your very life may well depend on those choices.

SUSTAINABILITY IS RELEVANT

Sustainability impacts nearly all human endeavors, and it is tied to nearly every social, academic, and professional arena. When you consider sustainability in relation to science, business, economics, political science, art, music, literature, history — or indeed any field of study — you will no doubt see that ideas and assumptions about sustainability are important both to the shape of those fields and to the work done within them. Indeed, debates and conversations about sustainability can be found all around us — in the news, on television, in film, and perhaps even among people in your own family or social circles. Therefore, understanding sustainability will help you understand an important facet of your future life and work.

SUSTAINABILITY IS COMPLEX

Sustainability is a complex subject that involves many different topics, conversations, and perspectives. Much of what we think and do concerning sustainability emerges from “expert” opinions on scientific, economic, and political issues, and it may seem daunting to try to form your own opinions based on your limited knowledge. Even the experts often disagree, and it can be confusing and difficult to sort through the complexity of the issues involved in the sustainability conversation. In fact, you may feel as if the subject is better left to those experts to address. However, you should recognize that it is that very complexity that makes the subject of sustainability worth addressing. Sustainability is a broad and diverse subject with no clear answer or set of answers.

SUSTAINABILITY IS INTERDISCIPLINARY

Along with its complexity, sustainability is also an interdisciplinary subject. This means that it can be addressed or analyzed from many different academic perspectives and that various “disciplines” can be combined in its understanding. Interdisciplinary thinking is about crossing the boundaries of specific, traditional fields of study to look at a problem or subject in more holistic, comprehensive ways. In this respect, sustainability combines a variety of disciplines, including science, economics, politics, humanities, and others. In fact, it is hard to think of an academic discipline that could not contribute to the sustainability conversation.

SUSTAINABILITY IS A “DISCOURSE”

All intellectual endeavors involve participation in an ongoing conversation called a “discourse.” This is not the same type of conversation you might have with a roommate or with a group of friends; it is the type of conversation that takes place among many people over many years in various methods of expression: books, essays, articles, speeches, and other kinds of articulations. All university students are expected to develop skills to absorb, assimilate, and synthesize information gathered from various sources within various discourses and to find their own voice within them. This is a basic pattern in the creation of knowledge. Sustainability is an emerging conversation or “discourse” in our society — its definition is still developing, and the reading, writing, thinking, and talking that you do can contribute to that definition.

SUSTAINABILITY IS POLITICAL

15 Because sustainability is concerned with how we use limited resources on the earth, it is essentially a political issue. All of the debates surrounding sustainability are political, since they seek to change the ways people think and act, often with the goal of influencing public policy and law.

SUSTAINABILITY IS RHETORICAL

Simply defined, rhetoric is about the ways in which speakers or writers attempt to persuade or motivate an audience. An effective writer will make careful choices in the language, delivery, timing, and other factors involved in a piece of writing because he or she wants those words to be understood, accepted, and acted on. Because sustainability is such an important, complex, and political issue, it is vital to analyze the words and images that are used to define it.

SUSTAINABILITY IS PERSONAL

Sustainability affects each of us on a personal level. The communities we live in, the foods we eat, our modes of transportation, the jobs we pursue — each of these aspects of our lives and countless others are shaped by sustainable (or unsustainable) choices. By learning more about sustainability, you will learn more about the world you live in and the influence it has on your own personal well-being. Furthermore, each of us has the ability to choose sustainable behaviors to improve our own lives and the lives of those around us. Your own perspective on sustainability will likely evolve, and that evolution will shape your values and decision-making, enabling you to create a healthier, happier, and more sustainable lifestyle.

RESPOND •

This selection represents an extended definitional argument. Make a list of the definitions, characterizations, and examples Weisser gives of the notion of sustainability, noting the paragraph in which each occurs. (The list may be quite long. Recall that explaining what something is not or how current ways of thinking about something differ from earlier ways of thinking about a related set of topics represents a kind of characterization.)

Take the list you created in response to question 1 and label each of the definitions, characterizations, or examples of sustainability in terms of the kind of definition it represents. (Chapter 9 on arguments of definition discusses kinds of definitions.)

In paragraph 4, Weisser writes that life-sustaining processes need to be or become “cyclical rather than linear.” How, specifically, does he use the extended example of aluminum soda cans in paragraph 5 to illustrate and clarify the contrast between linear and cyclical processes?

Study the Venn diagram that Weisser uses to illustrate the meaning of sustainability. (Slightly different versions of the diagram recur frequently in discussions of sustainability.) How does this diagram help clarify the notion of sustainability? Does it clarify or emphasize aspects of the notion that the written definition does not? How so? How does it help support the distinction Weisser draws between the earlier environmentalist movement and current discussions of sustainability (paragraph 9)?

Page 609Using the information in this chapter and other research that you do, write a definitional argument in which you define the concept of sustainability. Obviously, you’ll have to determine which aspects of this concept are most important for you. You’ll also want to spend some time considering why you find these aspects to be the most important. What you learn may become part of your discussion. (If you quote or paraphrase this selection or other sources you consult, be sure to study Chapter 20, Chapter 21, and Chapter 22 which give you practical advice about how to incorporate and document sources correctly.)