Making a Visual Argument: Claire Ironside, Apples to Oranges

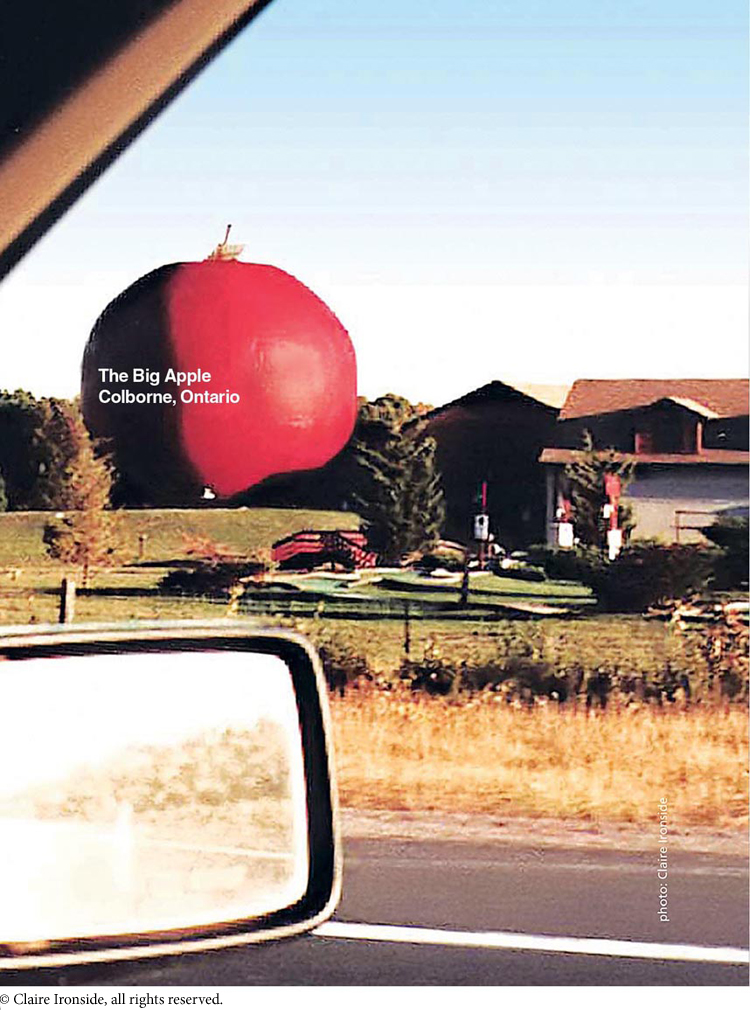

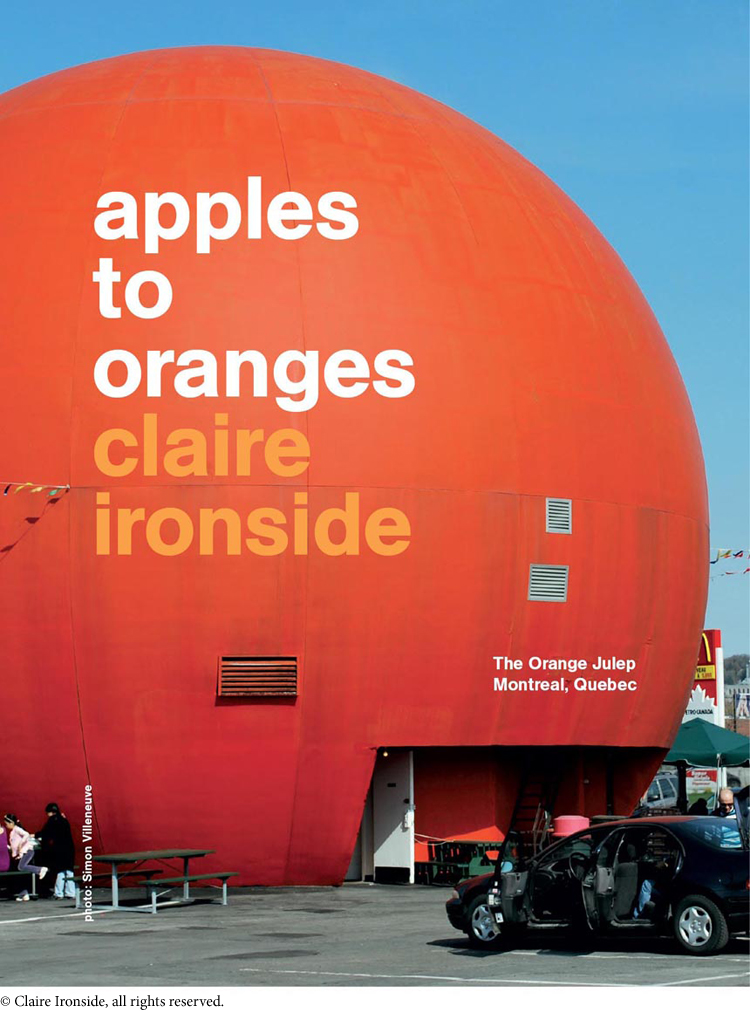

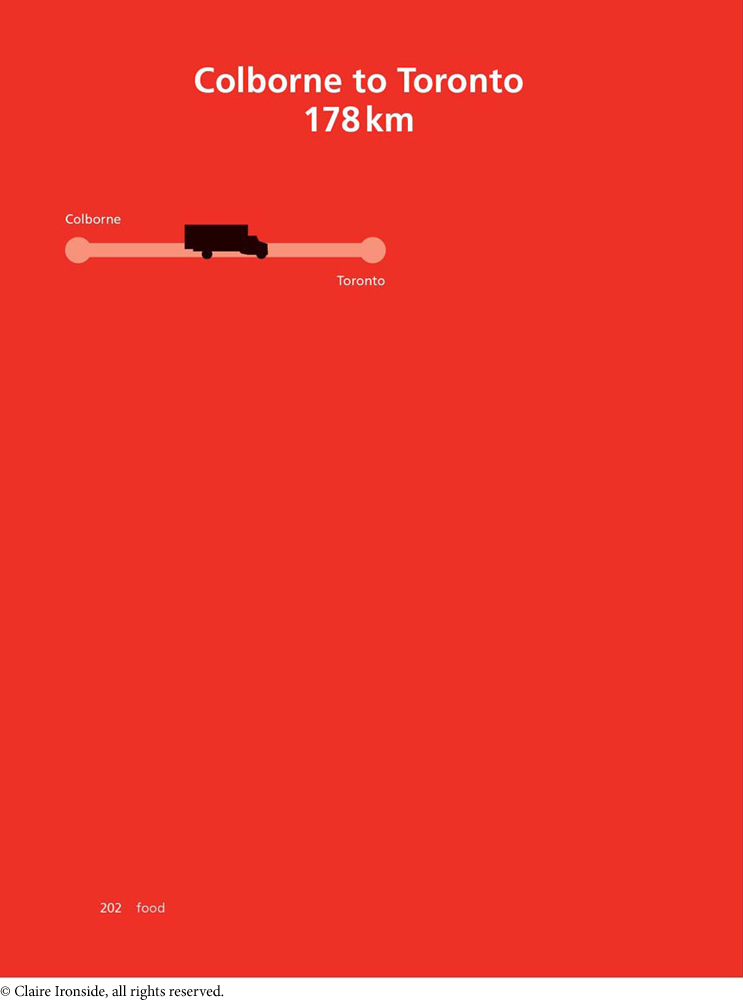

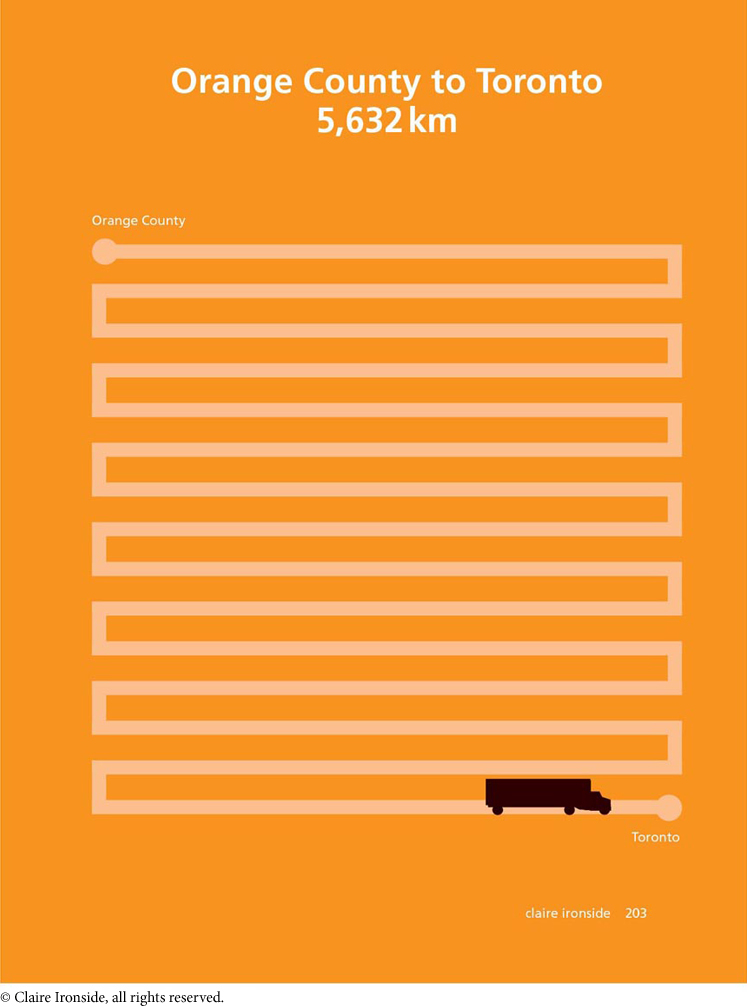

Claire Ironside is an instructor of illustration at Sheridan College School of Animation, Art, and Design in Ontario, Canada, where she teaches in the applied illustration program. With training in environmental and communication design studies, she is especially interested in issues of social engagement and activism as well as sustainability. This selection, “Apples to Oranges,” uses primarily visual means to make its argument. Its title plays on an everyday expression that is used when two things are compared unfairly because they are fundamentally different in one or more ways. We found this selection in Food, a 2008 book edited by John Knechtel. It appears in the Alphabet City series, copublished by Alphabet City Media and the MIT Press. Each volume focuses on a single theme and brings together artists and writers from diverse perspectives to encourage readers to question their basic assumptions about the topic. As you study this selection, think about what it would take to translate Ironside’s argument into words alone and whether doing so is even possible. (By the way, to convert kilometers to miles, multiply the number of kilometers by .62 to get a rough equivalent.)

Making a Visual Argument: Apples to Oranges

CLAIRE IRONSIDE

RESPOND •

What is Ironside’s explicit argument? What kind of argument is it (for example, of fact or definition)? Might she be making an implicit argument as well? If so, what would that implicit argument be, and what kind of argument is it?

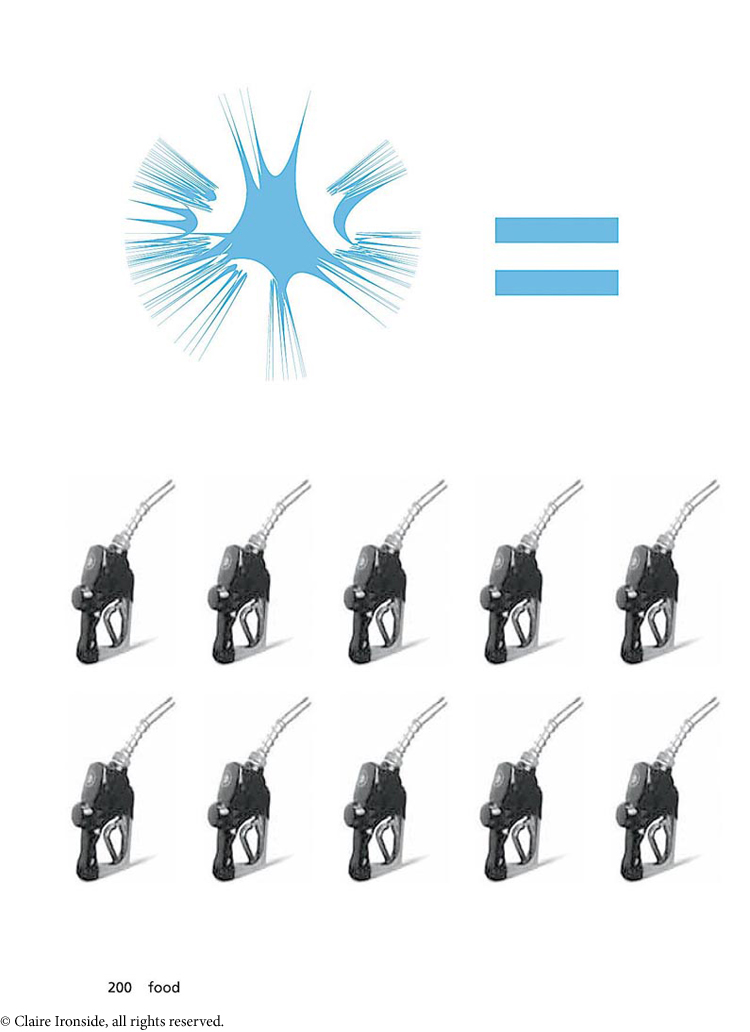

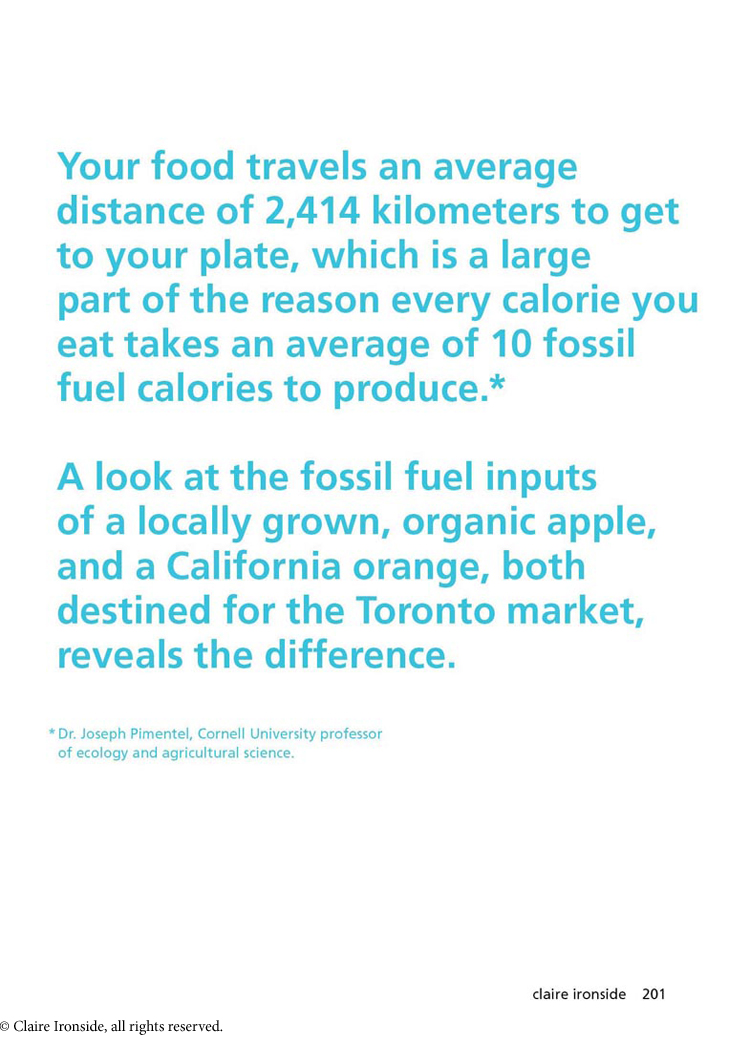

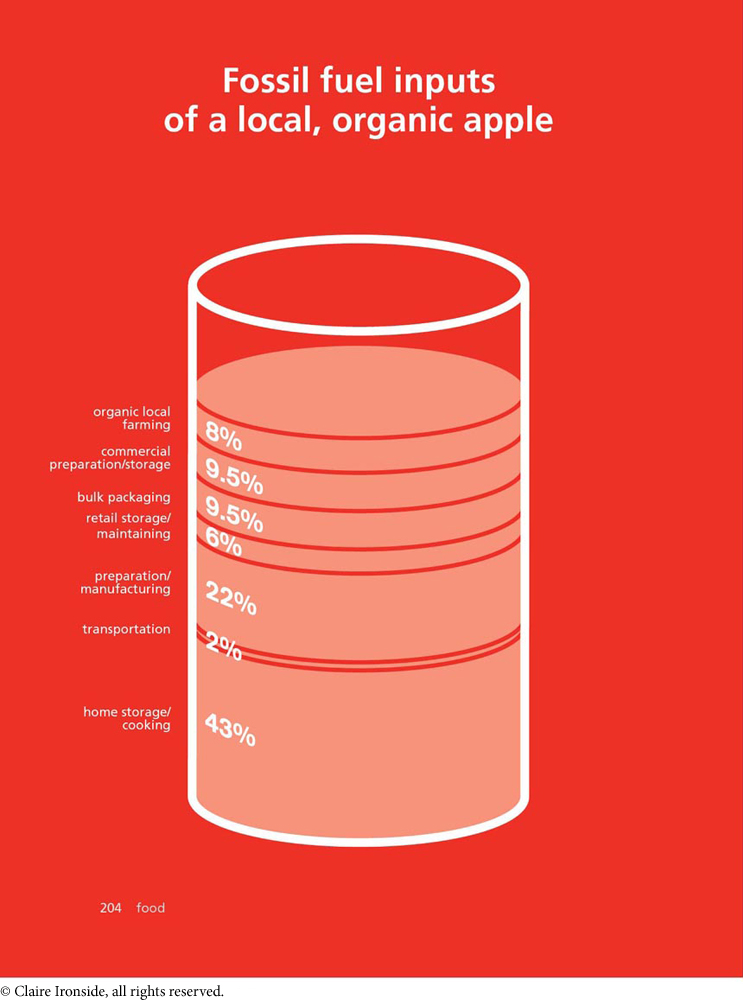

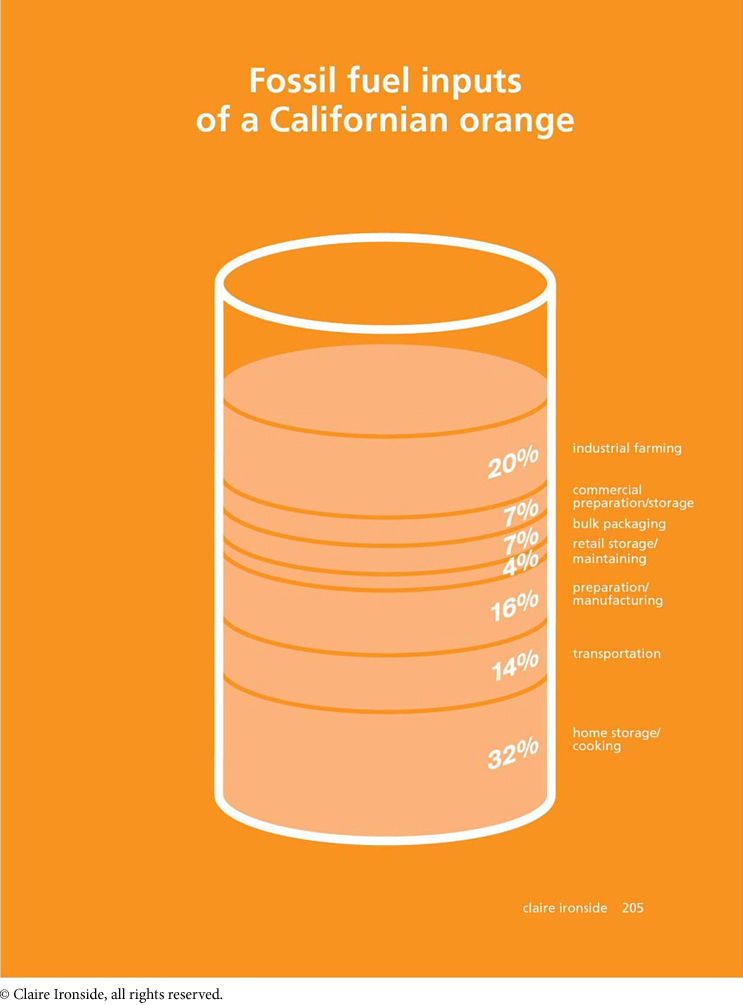

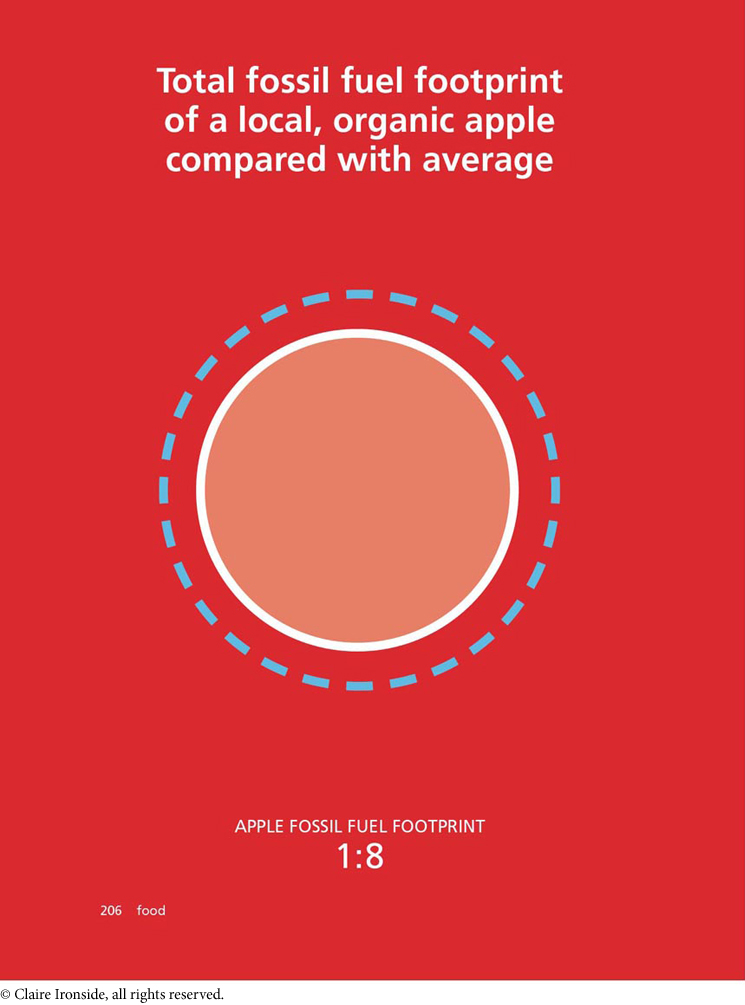

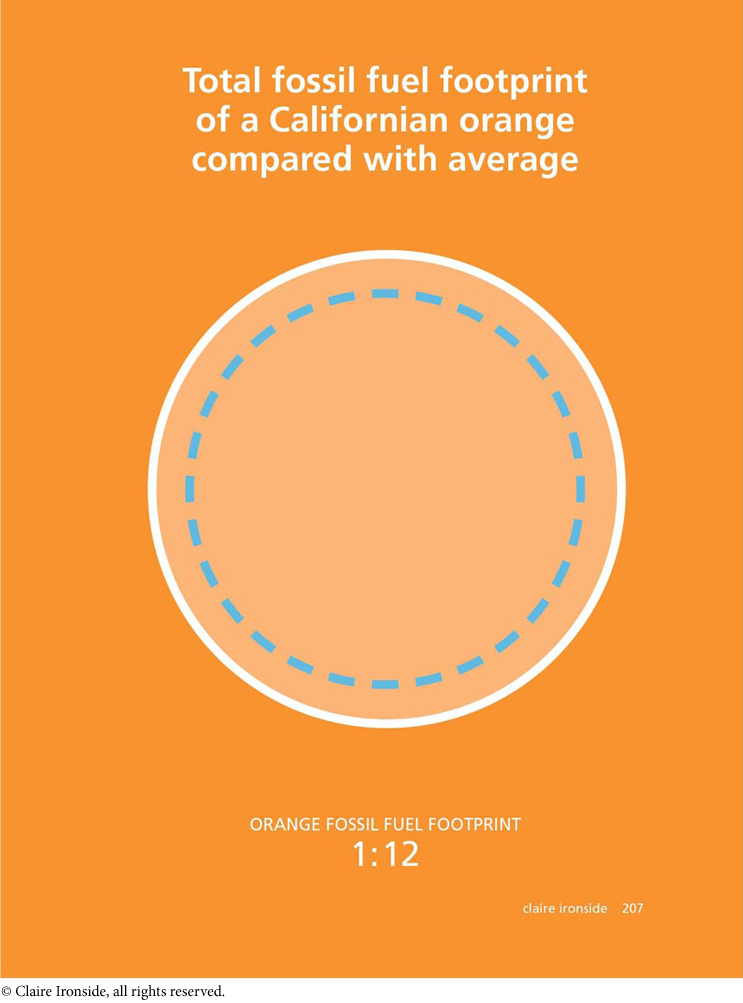

Analyze each pair of pages in Ironside’s argument. What does each juxtaposition contribute to her argument? How would you characterize the purpose of the comparison related to fossil-fuel inputs? What value might there be in the details given? What sorts of conclusions might we draw from this juxtaposition?

Evaluate the visual aspects of Ironside’s argument, including her choice of colors.

Ironside’s argument is part of a larger debate about carbon footprints. As this book goes to press, there are many Internet sites where you can calculate your own footprint. One is the Nature Conservancy’s “What’s My Carbon Footprint?” (http://www.nature.org/greenliving/carboncalculator/). After you’ve calculated your footprint at this site, visit others, and compare the calculations you get there. Write an essay in which you report your findings and discuss the factors that might account for any discrepancies. (For a discussion of arguments of fact and definition, see Chapters 8 and 9, respectively.)

Ironside takes a single fact (about the relationship between each calorie you consume and the fossil-fuel calories that are required to produce it) and illustrates this fact in a complex and sophisticated way. She compares two examples and demonstrates the nature of the average by showing an example that is above average and one that is below average. Choose a single fact about food and think of a visual argument that can illustrate it (as Ironside has here). You can either create the visual argument or describe it in words by discussing aspects of design (color, shape, images, and so on). (For a discussion of visual argument, see Chapter 14.)