Walter Benn Michaels, The Trouble with Diversity: How We Learned to Love Identity and Ignore Inequality

Walter Benn Michaels is currently a professor of English at the University of Illinois at Chicago, where he teaches literary theory and American literature. His influential essay “Against Theory,” coauthored with Steven Knapp, was published in 1982, and his books include The Shape of the Signifier: 1967 to the End of History (2004). This selection is an excerpt from the introduction to his book The Trouble with Diversity: How We Learned to Love Identity and Ignore Inequality (2006). Michaels begins this selection with an extended discussion of a literary text, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, one of the most famous American novels, which was published in 1925. Its central character, Jay Gatsby, seeks to win back Daisy Buchanan, a beautiful woman whom he had courted years earlier when he was a poor soldier but who had married a man from an “old money” background like her own. After meeting her, Gatsby changed his name to cover up his German immigrant roots at a time when people of most immigrant backgrounds were not fully accepted in elite society. He had also become wealthy, but his money was “new money”; though readers never learn exactly where it comes from, its sources are clearly disreputable and likely illegal. Many scholars now see The Great Gatsby as one of the best literary depictions and critiques of American life and values. While you read this selection, consider how his arguments mesh and do not mesh with those of Sheryll Cashin in the introduction to her book Place, Not Race.

The Trouble with Diversity: How We Learned to Love Identity and Ignore Inequality

WALTER BENN MICHAELS

“The rich are different from you and me” is a famous remark supposedly made by F. Scott Fitzgerald to Ernest Hemingway, although what made it famous — or at least made Hemingway famously repeat it — was not the remark itself but Hemingway’s reply: “Yes, they have more money.” In other words, the point of the story, as Hemingway told it, was that the rich really aren’t very different from you and me. Fitzgerald’s mistake, he thought, was that he mythologized or sentimentalized the rich, treating them as if they were a different kind of person instead of the same kind of person with more money. It was as if, according to Fitzgerald, what made rich people different was not what they had — their money — but what they were, “a special glamorous race.”

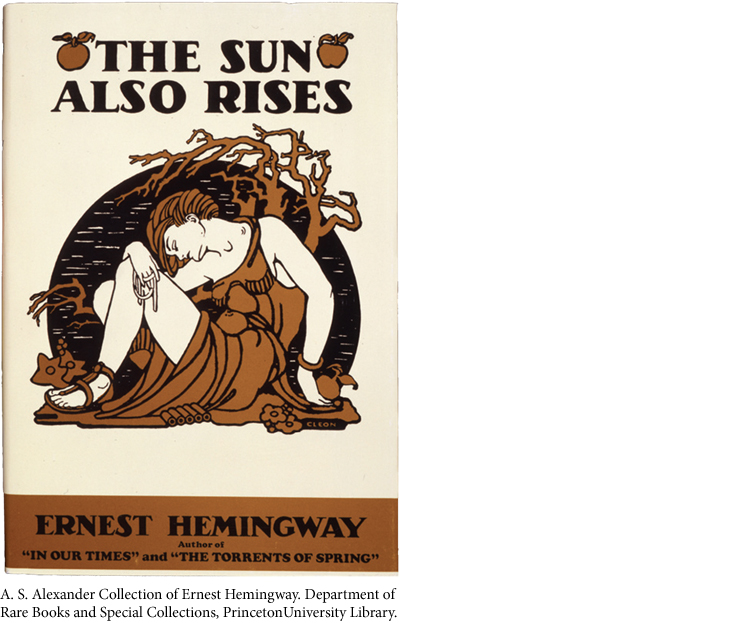

To Hemingway, this difference — between what people owned and what they were — seemed obvious, and it was also obvious that the important thing was what they were. No one cares much about Robert Cohn’s money in The Sun Also Rises, but everybody feels the force of the fact that he’s a “race-conscious” “little kike.” And whether or not it’s true that Fitzgerald sentimentalized the rich and made them more glamorous than they really were, it’s certainly true that he, like Hemingway, believed that the fundamental differences — the ones that really mattered — ran deeper than the question of how much money you had. That’s why in The Great Gatsby, the fact that Gatsby has made a great deal of money isn’t quite enough to win Daisy Buchanan back. Rich as he has become, he’s still “Mr. Nobody from Nowhere,” not Jay Gatsby but Jimmy Gatz. The change of name is what matters. One way to look at The Great Gatsby is as a story about a poor boy who makes good, which is to say, a poor boy who becomes rich — the so-called American dream. But Gatsby is not really about someone who makes a lot of money; it is instead about someone who tries and fails to change who he is. Or, more precisely, it’s about someone who pretends to be something he’s not; it’s about Jimmy Gatz pretending to be Jay Gatsby. If, in the end, Daisy Buchanan is very different from Jimmy Gatz, it’s not because she’s rich and he isn’t (by the end, he is) but because Fitzgerald treats them as if they really do belong to different races, as if poor boys who made a lot of money were only “passing” as rich. “We’re all white here,” someone says, interrupting one of Tom Buchanan’s racist outbursts. Jimmy Gatz isn’t quite white enough.

What’s important about The Great Gatsby, then, is that it takes one kind of difference (the difference between the rich and the poor) and redescribes it as another kind of difference (the difference between the white and the not-so-white). To put the point more generally, books like The Great Gatsby (and there have been a great many of them) give us a vision of our society divided into races rather than into economic classes. And this vision has proven to be extraordinarily attractive. Indeed, it’s been so attractive that the vision has survived even though what we used to think were the races have not. In the 1920s, racial science was in its heyday; now very few scientists believe that there are any such things as races. But many of those who are quick to remind us that there are no biological entities called races are even quicker to remind us that races have not disappeared; they should just be understood as social entities instead. And these social entities have turned out to be remarkably tenacious, both in ways we know are bad and in ways we have come to think of as good. The bad ways involve racism, the inability or refusal to accept people who are different from us. The good ways involve just the opposite: embracing difference, celebrating what we have come to call diversity.

Indeed, in the United States, the commitment to appreciating diversity emerged out of the struggle against racism, and the word diversity itself began to have the importance it does for us today in 1978 when, in Bakke v. Board of Regents, the Supreme Court ruled that taking into consideration the race of an applicant to the University of California (in this case, it was the medical school at UC Davis) was an acceptable practice if it served “the interest of diversity.” The point the Court was making here was significant. It was not asserting that preference in admissions could be given, say, to black people because they had previously been discriminated against. It was saying instead that universities had a legitimate interest in taking race into account in exactly the same way they had a legitimate interest in taking into account what part of the country an applicant came from or what his or her nonacademic interests were. They had, in other words, a legitimate interest in having a “diverse student body,” and racial diversity, like geographic diversity, could thus be an acceptable goal for an admissions policy.

5 Two things happened here. First, even though the concept of diversity was not originally connected with race (universities had long sought diverse student bodies without worrying about race at all), the two now came to be firmly associated. When universities publish their diversity statistics today, they’re not talking about how many kids come from Oregon. My university — the University of Illinois at Chicago — is ranked as one of the most diverse in the country, but well over half the students in it come from Chicago. What the rankings measure is the number of African Americans and Asian Americans and Latinos we have, not the number of Chicagoans.

And, second, even though the concept of diversity was introduced as a kind of end run around the historical problem of racism (the whole point was that you could argue for the desirability of a diverse student body without appealing to the history of discrimination against blacks and so without getting accused by people like Alan Bakke of reverse discrimination against whites), the commitment to diversity became deeply associated with the struggle against racism. Indeed, the goal of overcoming racism, which had sometimes been identified as the goal of creating a “color-blind” society, was now reconceived as the goal of creating a diverse, that is, a color-conscious, society.1 Instead of trying to treat people as if their race didn’t matter, we would not only recognize but celebrate racial identity. Indeed, race has turned out to be a gateway drug for all kinds of identities, cultural, religious, sexual, even medical. To take what may seem like an extreme case, advocates for the disabled now urge us to stop thinking of disability as a condition to be “cured” or “eliminated” and to start thinking of it instead on the model of race: we don’t think black people should want to stop being black; why do we assume the deaf want to hear?2

The general principle here is that our commitment to diversity has re-defined the opposition to discrimination as the appreciation (rather than the elimination) of difference. So with respect to race, the idea is not just that racism is a bad thing (which of course it is) but that race itself is a good thing. Indeed, we have become so committed to the attractions of race that (as I’ve already suggested above [. . .]) our enthusiasm for racial identity has been utterly undiminished by scientific skepticism about whether there is any such thing. Once the students in my American literature classes have taken a course in human genetics, they just stop talking about black and white and Asian races and start talking about black and European and Asian cultures instead. We love race, and we love the identities to which it has given birth.

Michaels offers several different arguments, but perhaps the richest and most complex is his causal argument that traces the effects of our traditional thinking about diversity. For more on how causal arguments work, see Chapter 11.

The fundamental point of this book is to explain why this is true. The argument, in its simplest form, will be that we love race — we love identity — because we don’t love class.3 We love thinking that the differences that divide us are not the differences between those of us who have money and those who don’t but are instead the differences between those of us who are black and those who are white or Asian or Latino or whatever. A world where some of us don’t have enough money is a world where the differences between us present a problem: the need to get rid of inequality or to justify it. A world where some of us are black and some of us are white — or biracial or Native American or transgendered — is a world where the differences between us present a solution: appreciating our diversity. So we like to talk about the differences we can appreciate, and we don’t like to talk about the ones we can’t. Indeed, we don’t even like to acknowledge that they exist. As survey after survey has shown, Americans are very reluctant to identify themselves as belonging to the lower class and even more reluctant to identify themselves as belonging to the upper class. The class we like is the middle class.

But the fact that we all like to think of ourselves as belonging to the same class doesn’t, of course, mean that we actually do belong to the same class. In reality, we obviously and increasingly don’t. “The last few decades,” as The Economist puts it, “have seen a huge increase in inequality in America.”4 The rich are different from you and me, and one of the ways they’re different is that they’re getting richer and we’re not. And while it’s not surprising that most of the rich and their apologists on the intellectual right are unperturbed by this development, it is at least a little surprising that the intellectual left has managed to remain almost equally unperturbed. Giving priority to issues like affirmative action and committing itself to the celebration of difference, the intellectual left has responded to the increase in economic inequality by insisting on the importance of cultural identity. So for thirty years, while the gap between the rich and the poor has grown larger, we’ve been urged to respect people’s identities — as if the problem of poverty would be solved if we just appreciated the poor. From the economic standpoint, however, what poor people want is not to contribute to diversity but to minimize their contribution to it — they want to stop being poor. Celebrating the diversity of American life has become the American left’s way of accepting their poverty, of accepting inequality.

10 I have three goals in writing this book. The first is to show how our current notion of cultural diversity — trumpeted as the repudiation of racism and >biological essentialism — in fact grew out of and perpetuates the very concepts it congratulates itself on having escaped. The second is to show how and why the American love affair with race — especially when you can dress race up as culture — has continued and even intensified. Almost everything we say about culture (that the significant differences between us are cultural, that such differences should be respected, that our cultural heritages should be perpetuated, that there’s a value in making sure that different cultures survive) seems to me mistaken, and this book will try to show why. And the third goal is — by shifting our focus from cultural diversity to economic equality — to help alter the political terrain of contemporary American intellectual life.

NOTES

1. Consciousness of color was, it goes without saying, always central to American society insofar as that society was a committedly racist one. The relevant change here — marked rather than produced by Bakke — involved (in the wake of both the successes and failures of the civil rights movement) the emergence of color consciousness as an antiracist position. The renewed black nationalism in the 1960s is one standard example of this transition, but the phenomenon is more general. You can get a striking sense of it by reading John Okada’s No-No Boy, a novel about the Japanese Americans who answered no to the two loyalty questions on the questionnaire administered to them at the relocation centers they were sent to during World War II. The novel itself, published in 1957, is a pure product of the civil rights movement, determined to overcome race (and ignore class) in the imagination of a world in which people are utterly individualized — “only people.” It began to become important, however, as an expression of what Frank Chin, in an article written in 1976 and included as an appendix to the current edition, calls “yellow soul,” and when it’s taught today in Asian American literature classes, reading it counts toward the fulfillment of diversity requirements that Okada himself would not have understood.

2. Simi Linton, Claiming Disability (New York: New York University Press, 1998), 96.

3. The relations between race and class have been an important topic in American writing at least since the 1930s, and in recent years they have, in the more general form of the relations between identity and inequality, been the subject of an ongoing academic discussion. Some of the more notable contributions include Culture and Equality (2000) by Brian Barry, Redistribution or Recognition (2003), an exchange between Nancy Fraser and Axel Honneth, and The Debate on Classes (1990), featuring an important essay by Erik Olin Wright and a series of exchanges about that essay. And in my particular field of specialization, American literature, Gavin Jones is about to publish an important and relevant book called American Hunger. I cite these texts in particular because, in quite different ways, they share at least some of my skepticism about the value of identity. And I have myself written in an academic context about these issues, most recently in The Shape of the Signifier (2004). The Trouble with Diversity is in part an effort to make some of the terms of the discussion more vivid to a more general audience. More important, however, it is meant to advance a particular position in that discussion, an argument that the concept of identity is incoherent and that its continuing success is a function of its utility to neoliberalism.

4. The Economist, December 29, 2004.

RESPOND •

What, for Walter Benn Michaels, is the real issue that American society needs to confront? How, for him, does defining diversity in terms of a celebration of difference, especially ethnic difference, prevent Americans from both seeing the real issue and doing anything about it? In what ways does our society’s focus on ethnic and cultural diversity necessarily perpetuate racism and biological essentialism (paragraph 10)?

Why and how are these issues relevant to discussions of diversity on campus in general? On the campus you attend?

Later in this introduction, Michaels, a liberal, points out ways in which both conservatives and liberals in American public life, first, focus on racial or ethnic differences rather than issues of social inequality and, second, benefit from doing so. In a 2004 essay, “Diversity’s False Solace,” he notes:

[W]e like policies like affirmative action not so much because they solve the problem of racism but because they tell us that racism is the problem we need to solve. . . . It’s not surprising that universities of the upper middle class should want their students to feel comfortable [as affirmative action programs enable and encourage them to do]. What is surprising is that diversity should have become the hallmark of liberalism.

Analyze the argument made in this paragraph as a Toulmin argument. (For a discussion of Toulmin argumentation, see Chapter 7.)

How would you characterize Michaels’s argument? In what ways is it an argument of fact? A definitional argument? An evaluative argument? A causal argument? A proposal? (For a discussion of these kinds of arguments, see Chapters 8, 9, 10, 11, and 12.)

Imagine a dialogue between Walter Benn Michaels and Sheryll Cashin, author of the previous selection. What would they agree on with respect to diversity on campuses? And where might there be disagreements? Why?

This chapter has provided many perspectives on an issue that is hotly debated on American campuses and in American society at large — diversity. Should diversity be something that schools strive for? If so, what kinds of diversity? What should a diverse campus look like, and why? Write a proposal essay in which you define and justify the sort(s) of diversity, if any, that your school should aim for. Seek to draw widely on the perspectives that you’ve read in this chapter — in terms of topics discussed and also approaches to those or other topics that you might consider. If you completed the assignment in question 6 for the first selection in this chapter (“Making a VIsual Argument: Diversity Posters” in Chapter 26, “What Should Diversity on Campus Mean and Why?”), you will surely want to reread your essay, giving some thought to how and why your understanding of diversity has or has not changed as you have read the selections in this chapter. (For a discussion of proposals, see Chapter 12.)