Deena Prichep, A Campus More Colorful than Reality: Beware That College Brochure

678

Although the events this story refers to took place over a decade earlier, the questions they raise are still live wires on many campuses, something this feature, which aired on National Public Radio’s Weekend Edition Sunday on December 29, 2013, demonstrates. As sociologist Tim Pippert, who is interviewed in the feature, explains, colleges and universities want and need to market diversity, and the diversity represented in their promotional materials doesn’t necessarily match campus demographics. This disparity leads to a number of questions, which this news feature and the accompanying information from the NPR Web site explore. (You can listen to the actual broadcast at n.pr/11PACBR.) Deena Prichep is a freelance journalist whose media include print and radio. Based in Portland, Oregon, she is a frequent contributor to various National Public Radio programs and to the Northwest News Network, and her radio features have appeared on Public Radio International’s The World and Marketplace while her articles have appeared on Salon.com, in Vegetarian Times, and in Portland Monthly. She also blogs at Mostly Foodstuffs. As you listen to the news broadcast and read the information from the NPR Web site, consider how the two are similar, how they differ, and why that may be the case. Likewise, give some thought to the dilemma colleges and universities face and the possible alternatives they might have.

A Campus More Colorful Than Reality: Beware That College Brochure

DEENA PRICHEP

NPR Transcript

JENNIFER LUDDEN, HOST: When it’s time to apply to college, for many high school kids the process begins by leafing through a university brochure. But as Deena Prichep reports, when it comes to diversity, those glossy images may not paint an accurate picture.

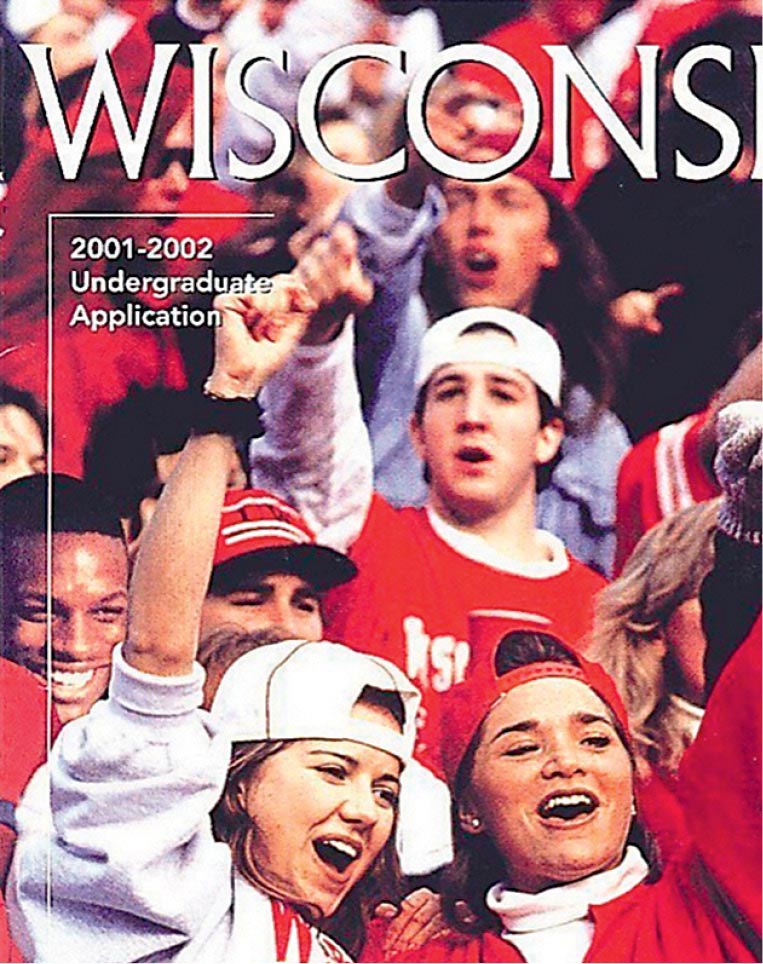

DEENA PRICHEP, BYLINE: In 2000, Diallo Shabazz was a student at the University of Wisconsin. And he stopped by the admissions office.

DIALLO SHABAZZ: And one of the admissions counselors walked up to me and said, “Diallo, did you see yourself in the admissions booklet? Actually, you’re on the cover this year.”

679

PRICHEP: Shabazz remembered seeing a cover shot of students at a football game. But he’d never been to a football game.

5 SHABAZZ: And so I flipped back and that’s when I saw my head cut off, and kind of pasted onto the front cover of the admissions booklet.

PRICHEP: This Photoshopped image became a classic example of how colleges miss the mark on diversity. Wisconsin stressed that it was just one person’s bad choice. But Shabazz sees it as part of a bigger problem.

SHABAZZ: The admissions department that we’ve been talking about I believe was on the fourth floor, and the multicultural student center was on the second floor of that same building. So you didn’t need to create false diversity in a picture. All you really needed to do was go downstairs.

TIM PIPPERT: Diversity is something that’s being marketed.

PRICHEP: Tim Pippert is a sociologist at Augsberg College in Minnesota. He says that even without Photoshop colleges try to shape the picture.

10 PIPPERT: They’re trying to sell a campus climate. They’re trying to sell a future. Campuses are trying to say: If you come here, you’ll have a good time and you’ll fit in.

680

PRICHEP: Pippert and his researchers looked at over ten thousand images from college brochures. They compared the racial breakdown of students in the pictures to the colleges’ actual demographics. And they found that, overall, the whiter the school, the more the brochures skewed diversity — especially for certain groups.

PIPPERT: So, for example, when we looked at African-Americans in those schools that were predominantly white, the actual percentage in those campuses was only about 5 percent of the student body. They were photographed at 14.5 percent.

PRICHEP: While that may not sound like a lot, it’s an overrepresentation of 188 percent. But where should colleges draw the line? Jim Rawlins directs admissions at the University of Oregon. He’s also the past president of the National Association for College Admission Counseling.

JIM RAWLINS: If your campus is 20 percent racially and ethnically diverse, and I were to look at all your photos and you were 30 percent, is 30 unreasonable? Is 30 OK, but 35 would be too far? Is 20? I mean, where’s that number?

15 PRICHEP: Rawlins says that showing inflated diversity can actually be a step toward creating a more diverse campus. It helps students imagine themselves at those schools. But balancing representation and aspiration is difficult.

RAWLINS: I also wouldn’t want to suggest it’s something that we all feel we can easily quantify, and start counting faces in pictures and reach our answers to whether we’re doing this right or not. I think very much any campus that wants to do this right has to talk with the students they have and see how they’re doing.

PRICHEP: We checked in with a group of twelfth graders at Jefferson High School in Portland, Oregon, who are awash in college brochures. And none of them had any illusions, like Tobias Kelly.

TOBIAS KELLY: I see these as ads. So I think it’s best if you are trying to go to a school to visit it for yourself, so you can really see, ’cause this can fool you sometimes.

PRICHEP: The students all stress that their highest priority is finding a school that will give them the best education. But many, like Brandon Williams, say that diversity is a part of that.

20 BRANDON WILLIAMS: When you go to college, it’s not just about like the classrooms, but it’s also about like the stuff you learn from the people.

PRICHEP: And showing who those people are is something colleges continue to navigate. After his Photoshop experience, you’d think Diallo Shabazz would insist colleges stay absolutely true to the numbers. But Shabazz thinks that colleges can paint a picture with an eye toward the future — and they should.

681

SHABAZZ: I think that universities have a responsibility to portray diversity on campus, you know. And to portray the type of diversity that they would like to create — it shows what their value systems are. At the same time, I think they have a responsibility to be actively engaged in creating that diversity on campus that goes deeper than just what’s in the picture.

PRICHEP: And Shabazz hopes that if schools take on that responsibility, the picture may change. For NPR News, I’m Deena Prichep.

(Soundbite of music)

LUDDEN: You’re listening to NPR News.

RESPOND •

What evaluative argument is Prichep making in this radio feature and in the accompanying materials from the NPR Web site? What specific problems are discussed, and what possible solutions are proposed? (Note that, importantly, Prichep is not making an actual proposal although she is likely presuming that, after hearing the radio broadcast and/or reading the materials on the Web site, readers will want to take a stance on the issues discussed; that is, they will have proposals they wish to offer.) How are the various proposals for dealing with the problems Prichep discusses evaluated? (See Chapter 10 on criteria of evaluation in evaluative arguments; you may also want to review Chapter 12 so that you can understand clearly why Prichep is not, in fact, making a proposal argument.)

Does the information provided in this feature surprise you? Why or why not?

How sympathetic are you to the arguments made in this selection that promotional materials for a college must be aspirational, that is, they should represent what the university would like to be like? Can we distinguish such arguments from the argument that promotional materials represent the college as it wishes to be perceived at this time? What is the difference between the two arguments? Are there consequences to these differences?

How do the two versions of this feature — the transcript and audio link, on the one hand, and the printed information given on the NPR Web site, on the other — compare? What might account for the similarities? The differences?

Take Prichep’s challenge. Examine carefully the promotional materials, whether print or electronic, for your college or university. How do they represent or fail to represent current reality? Do not consider issues of race or ethnicity alone; consider other kinds of diversity as well. (Also spend some time thinking about whether certain important kinds of diversity may not be visible.) You’ll want to compare what you find with the latest available statistics about diversity on your campus. Once you’ve done this research, you have two options: write a factual argument about what you found or write an evaluative argument examining what you found. (Chapter 8 will help you with the first choice, while Chapter 10 will help you with the second.) This activity is also a great opportunity to work with a group. Each group should take a topic like race/ethnicity, sex/gender, or international students as its focus, and share what it finds.

Click to navigate to this activity.