10bGet the most from peer review.

In addition to your own critical appraisal and that of your instructor (10c), you will probably want to get responses to your draft from friends, classmates, or colleagues. In a writing course, you may be asked to respond to the work of your peers as well as to seek responses from them.

Guidelines for Peer Response

AT A GLANCE

Guidelines for Peer Response

- Initial thoughts. What are the main strengths and weaknesses of the draft? What might confuse readers? What is the most important thing the writer says in the draft? What will readers want to know more about?

- Assignment. Does the draft carry out the assignment?

- Title and introduction. Do the title and introduction tell what the draft is about and catch readers’ interest? How else might the draft begin?

- Thesis and purpose. Paraphrase the thesis: In this paper, the writer will…. Does the draft fulfill that promise?

- Audience. How does the draft interest and appeal to its audience?

- Rhetorical stance. Where does the writer stand? What words indicate the stance?

- Supporting points. List the main points, and review them one by one. How well does each point support the thesis? Do any need more -explanation? Do any seem confusing or boring?

- Visuals and design. Do visuals, if any, add to the key points? Is the design clear and effective?

- Organization and flow. Is the writing easy to follow? How effective are transitions within sentences, between sentences, and between paragraphs?

- Conclusion. Does the draft conclude memorably? Is there another way it might end?

Understanding Peer Review

FOR MULTILINGUAL WRITERS

Understanding Peer Review

If you are not used to giving or receiving criticisms directly, you may be uneasy with a classmate’s challenges to your work. However, constructive criticism is appropriate to peer review. Your peers will also expect you to offer your questions, suggestions, and insights.

Serving as a peer reviewer

One of the main goals of a peer reviewer is to help the writer see his or her draft differently. When you review a draft, you want to show the writer what does and doesn’t work about particular aspects of the draft. Visually marking the draft can help the writer absorb at a glance the revisions you suggest.

Go to the Thinking Visually exercise to analyze this image

REVIEWING A PRINT DRAFT

When working with a hard copy of a draft, write compliments in the left margin and critiques, questions, and suggestions in the right margin. As long as you explain what your symbols mean, you can also use boxes, circles, single and double underlining, highlighting, or other visual annotations as shorthand for what you have to say about the draft.

REVIEWING A COMPUTER DRAFT

If the draft is an electronic file, the reviewer should save the document in a peer-review folder under an easy-to-recognize name. It’s wise to include the writer’s name, the assignment, the number of the draft, and the reviewer’s initials. For example, the reviewer Ann G. Smith might name the file for the first draft of Javier Jabari’s first essay jabari.essay1.d1.ags.

The reviewer can then use the word-processing program to add comments, questions, and suggestions to the text. Most such programs have a TRACK CHANGES tool that can show changes to the document in a different color and a COMMENT function that allows you to type a note in the margin. If your word processor doesn’t have a COMMENT function, you can comment in footnotes instead.

Watch and respond to the video Lessons from being a peer reviewer.

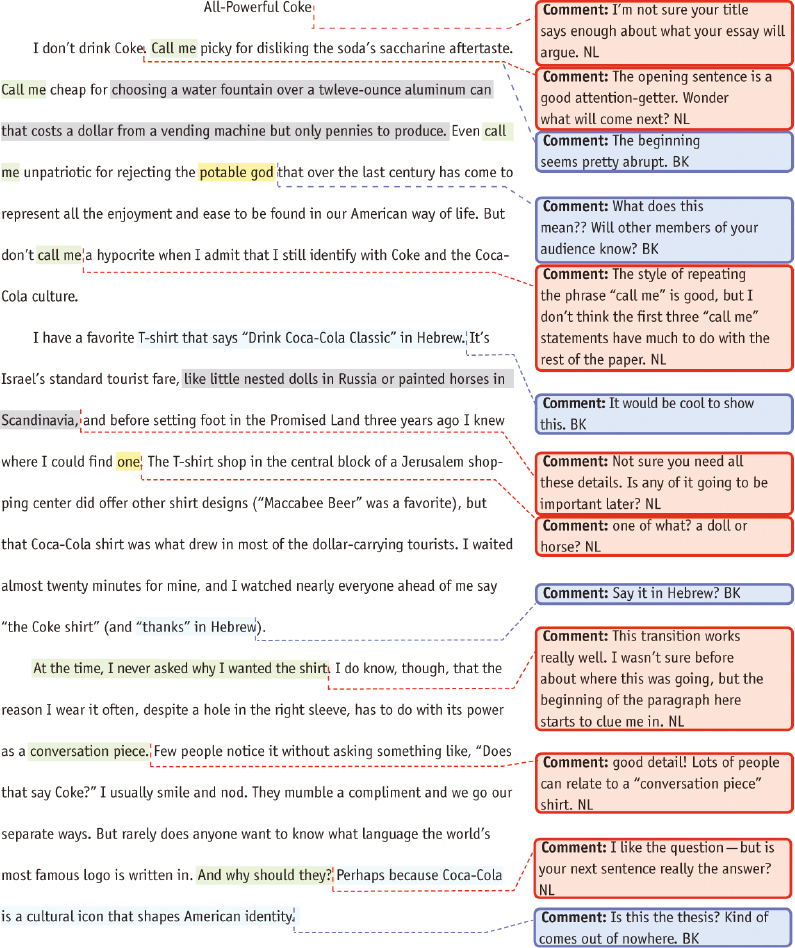

Reviews of Emily Lesk’s draft

See the first three paragraphs of Emily Lesk’s draft, as reviewed electronically by two students, Beatrice Kim and Nastassia Lopez. (You’ll find earlier appearances of Emily’s work in 5g, 6d, and 7a.) Beatrice and Nastassia decided to use highlighting for particular purposes: green for material they found effective, yellow for language that seemed unclear, blue for material that could be expanded, and gray for material that could be deleted.

As this review shows, Nastassia and Bea agree on some of the major problems—and good points—in Emily’s draft. The comments on the draft, however, reveal their different responses. You, too, will find that different readers do not always agree on what is effective or ineffective. In addition, you may find that you simply do not agree with their advice.

You can often proceed efficiently by looking first for areas of agreement (everyone was confused by this sentence—I’d better review it) or strong disagreement (one person said my conclusion was “perfect,” and someone else said it “didn’t conclude”—better look carefully at that paragraph again).

Getting help from peer reviewers

Remember that your reviewers should be acting as coaches, not judges, and that their job is to help you improve your essay as much as possible. Listen to and read their comments carefully. If you don’t understand a particular suggestion, ask for clarification, examples, and so on. Remember, too, that reviewers are commenting on your writing, not on you, so be open and responsive to what they recommend. But you are the final authority on your essay; you will decide which suggestions to follow and which to disregard.

Go to the Thinking Visually exercise to analyze this image

Watch and respond to the video Lessons from peer review.