13eThink critically about fallacies.

Fallacies have traditionally been viewed as serious flaws that damage the effectiveness of an argument. But arguments are ordinarily fairly complex in that they always occur in some specific rhetorical situation and in some particular place and time; thus what looks like a fallacy in one situation may appear quite different in another. The best advice is to learn to identify fallacies but to be cautious in jumping to quick conclusions about them. Rather than thinking of them as errors you can use to discredit an arguer, you might think of them as barriers to common ground and understanding, since they often shut off rather than engender debate.

Verbal fallacies

AD HOMINEM

Ad hominem charges make a personal attack rather than focusing on the issue at hand.

Who cares what that fat loudmouth says about the health care system?

Who cares what that fat loudmouth says about the health care system?

GUILT BY ASSOCIATION

Guilt by association attacks someone’s credibility by linking that person with a person or activity the audience considers bad, suspicious, or untrustworthy.

She does not deserve reelection; her husband had extramarital affairs.

She does not deserve reelection; her husband had extramarital affairs.

FALSE AUTHORITY

False authority is often used by advertisers who show famous actors or athletes testifying to the greatness of a product about which they may know very little.

He’s today’s greatest NASCAR driver—and he banks at National Mutual!

He’s today’s greatest NASCAR driver—and he banks at National Mutual!

BANDWAGON APPEAL

Bandwagon appeal suggests that a great movement is underway and the reader will be a fool or a traitor not to join it.

This new phone is everyone’s must-have item. Where’s yours?

This new phone is everyone’s must-have item. Where’s yours?

FLATTERY

Flattery tries to persuade readers by suggesting that they are thoughtful, intelligent, or perceptive enough to agree with the writer.

You have the taste to recognize the superlative artistry of Bling diamond jewelry.

You have the taste to recognize the superlative artistry of Bling diamond jewelry.

IN-CROWD APPEAL

In-crowd appeal, a special kind of flattery, invites readers to identify with an admired and select group.

Want to know a secret that more and more of Middletown’s successful young professionals are finding out about? It’s Mountainbrook Manor condominiums.

Want to know a secret that more and more of Middletown’s successful young professionals are finding out about? It’s Mountainbrook Manor condominiums.

VEILED THREAT

Veiled threats try to frighten readers into agreement by hinting that they will suffer adverse consequences if they don’t agree.

If Public Service Electric Company does not get an immediate 15 percent rate increase, its services to you may be seriously affected.

If Public Service Electric Company does not get an immediate 15 percent rate increase, its services to you may be seriously affected.

FALSE ANALOGY

False analogies make comparisons between two situations that are not alike in important respects.

The volleyball team’s sudden descent in the rankings resembled the sinking of the Titanic.

The volleyball team’s sudden descent in the rankings resembled the sinking of the Titanic.

BEGGING THE QUESTION

Begging the question is a kind of circular argument that treats a debatable statement as if it had been proved true.

Television news covered that story well; I learned all I know about it by watching TV.

Television news covered that story well; I learned all I know about it by watching TV.

POST HOC FALLACY

The post hoc fallacy (from the Latin post hoc, ergo propter hoc, which means “after this, therefore caused by this”) assumes that just because B happened after A, it must have been caused by A.

We should not rebuild the town docks because every time we do, a big hurricane comes along and damages them.

We should not rebuild the town docks because every time we do, a big hurricane comes along and damages them.

NON SEQUITUR

A non sequitur (Latin for “it does not follow”) attempts to tie together two or more logically unrelated ideas as if they were related.

If we can send a spaceship to Mars, then we can discover a cure for cancer.

If we can send a spaceship to Mars, then we can discover a cure for cancer.

EITHER-OR FALLACY

The either-or fallacy insists that a complex situation can have only two possible outcomes.

If we do not build the new highway, businesses downtown will be forced to close.

If we do not build the new highway, businesses downtown will be forced to close.

HASTY GENERALIZATION

A hasty generalization bases a conclusion on too little evidence or on bad or misunderstood evidence.

I couldn’t understand the lecture today, so I’m sure this course will be impossible.

I couldn’t understand the lecture today, so I’m sure this course will be impossible.

OVERSIMPLIFICATION

Oversimplification claims an overly direct relationship between a cause and an effect.

If we prohibit the sale of alcohol, we will get rid of binge drinking.

If we prohibit the sale of alcohol, we will get rid of binge drinking.

STRAW MAN

A straw-man argument misrepresents the opposition by pretending that opponents agree with something that few reasonable people would support.

My opponent believes that we should offer therapy to the terrorists. I disagree.

My opponent believes that we should offer therapy to the terrorists. I disagree.

Visual fallacies

Fallacies can also take the form of misleading images. The sheer power of images can make them especially difficult to analyze—people tend to believe what they see. Nevertheless, photographs and other visuals can be manipulated to present a false impression.

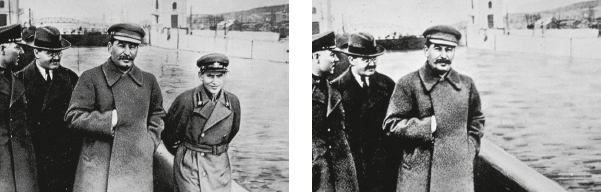

MISLEADING PHOTOGRAPHS

Faked or altered photos have existed since the invention of photography. On the following page, for example, is a photograph of Joseph Stalin, the Soviet Union’s leader from 1929 to 1953, with his commissar Nikolai Yezhov. Stalin and the commissar had a political disagreement that resulted in Yezhov’s execution in 1940. The second image shows the same photo after Stalin had it doctored to rewrite history.

Today’s technology makes such photo alterations easier than ever. But photographs need not be altered to try to fool viewers. Think of all the photos that make a politician look misleadingly bad or good. In these cases, you should closely examine the motives of those responsible for publishing the images.

MISLEADING CHARTS AND GRAPHS

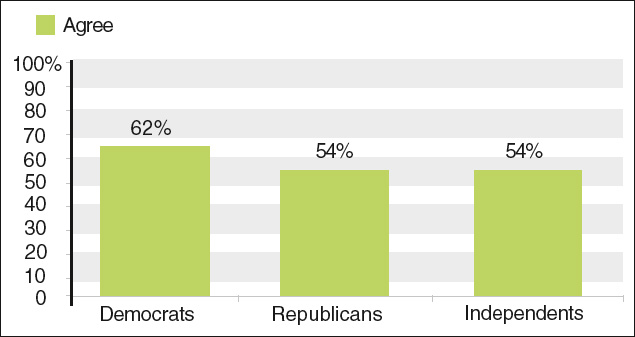

Facts and statistics, too, can be presented in ways that mislead readers. For example, the following bar graph purports to deliver an argument about how differently Democrats, on the one hand, and Republicans and Independents, on the other, felt about an issue:

DATA PRESENTED MISLEADINGLY

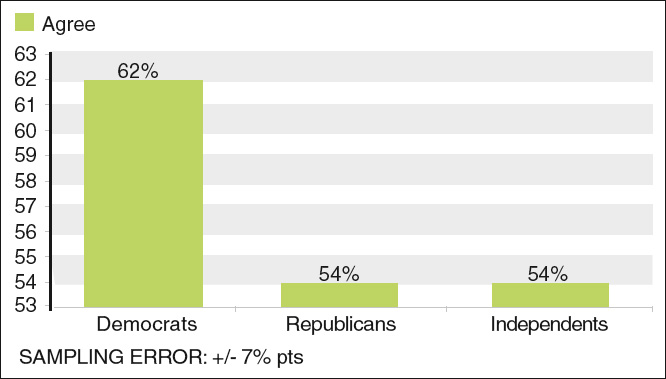

Look closely and you’ll see a visual fallacy: the vertical axis starts not at zero but at 53 percent, so the apparently large difference between the groups is misleading. In fact, a majority of all respondents agree about the issue, and only eight percentage points separate Democrats from Republicans and Independents (in a poll with a margin of error of 1/2 seven percentage points). Here’s how the graph would look if the vertical axis began at zero:

DATA PRESENTED MORE ACCURATELY