5dConsider your purpose and stance as a communicator.

Whether you choose to communicate for purposes of your own or have that purpose set for you by an instructor or employer, you should consider the purpose for any communication carefully. For the writing you do that is not connected to a class or work assignment, your purpose may be very clear to you: you may want to convince neighbors to support a community garden, get others in your office to help keep the kitchen clean, or tell blog readers what you like or hate about your new phone. Even so, analyzing exactly what you want to accomplish and why can make you a more effective communicator.

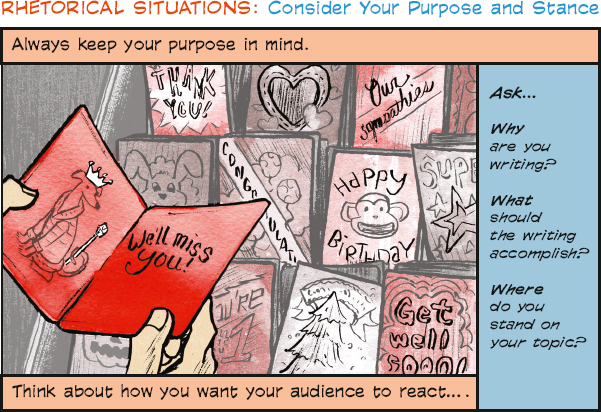

Go to the Thinking Visually exercise to analyze this image

Purposes for academic assignments

An academic assignment may clearly explain why, for whom, and about what you are supposed to write. But sometimes college assignments seem to come out of the blue, with no specific purpose, audience, or topic. Because comprehending the assignment fully and accurately is crucial to your success in responding to it, make every effort to understand what your instructor expects.

- What is the primary purpose of the piece of writing—to explain? to persuade? to entertain? some other purpose?

- What purpose did the person who gave you the assignment want to achieve—to make sure you have understood something? to evaluate your thinking and writing abilities? to test your ability to think outside the box?

- What are your own purposes in this piece of writing—to respond to a question? to learn about a topic? to communicate your ideas? to express feelings? How can you achieve these goals?

- What, exactly, does the assignment ask you to do? Look for such words as analyze, classify, compare, define, describe, explain, prove, and survey. Remember that these words may differ in meaning from discipline to discipline.

Stances for academic assignments

Thinking about your own position as a communicator and your attitude toward your text—your rhetorical stance—is just as important as making sure you communicate effectively.

- Where are you coming from on this topic? What is your overall attitude toward your topic? How strong are your opinions?

- What social, political, religious, personal, or other influences account for your attitude? Will you need to explain any of these influences?

- What is most interesting to you about the topic? Why do you care?

- What conclusions do you think you’ll reach as you complete your text?

- How will you establish your credibility? How will you show you are knowledgeable and trustworthy?

- How will you convey your stance? Should you use words alone, combine words and images, include sound, or something else?

Assignments

TALKING THE TALK

Assignments

“How do instructors come up with these assignments?” Assignments, like other kinds of writing, reflect particular rhetorical contexts that vary from instructor to instructor. Assignments also change over time. The assignment for an 1892 college writing contest was to write an essay “on coal.” In the twentieth century, many college writing assignments asked students to write about their own experiences; in research conducted for this textbook in the 1980s, the most common writing assignment was a personal narrative. As expectations for college students—and the needs of society—change over time, assignments also change. Competing effectively in today’s workforce calls for high-level thinking, for being able to argue convincingly, and for knowing how to do the research necessary to support a claim—so it’s no surprise that college writing courses today give students assignments that allow them to develop such skills. A recent study of first-year college writing in the United States found that by far the most common assignment today asks students to compose a researched argument. (See Chapters 12–14.)