8cUse effective methods of development.

As noted in 7d, there are several common methods of development. You can use them to develop paragraphs.

Narrative

A narrative paragraph uses the chronological elements of a story to develop a main idea. The following is one student’s narrative paragraph that tells a personal story to support a point about the dangers of racing bicycles with flimsy alloy frames:

People who have been exposed to the risk of dangerously designed bicycle frames have paid too high a price. I saw this danger myself in last year’s Putney Race. An expensive graphite frame failed, and the rider was catapulted onto Vermont pavement at fifty miles per hour. The pack of riders behind him was so dense that other racers crashed into a tangled, sliding heap. The aftermath: four hospitalizations. I got off with some stitches, a bad road rash, and severely pulled tendons. My Italian racing bike was pretzeled, and my racing was over for that summer. Others were not so lucky. An Olympic hopeful, Brian Stone of the Northstar team, woke up in a hospital bed to find that his cycling was over—and not just for that summer. His kneecap had been surgically removed. He couldn’t even walk.

Description

A descriptive paragraph uses specific details to create a clear impression. Notice how the following paragraph includes details to describe the appearance of the skyscraper and its effect on those who see it.

The Chrysler Building, completed in 1930, still attracts the eyes of tourists and New Yorkers alike with its shiny steel exterior. The Chrysler cars of the era are incorporated into the design: the eagle-head gargoyles on the upper vertices of the building are shaped like the automobiles’ hood ornaments, and winged details imitate Chrysler radiator caps. At night, an elaborate lighting scheme spotlights the sleek, powerful eagles from below—turning them into striking silhouettes—and picks out each of the upper stories’ famed triangular windows, arching up into the darkness like the rays of a stylized sun.

Definition

You may often need to write an entire paragraph in order to define a word or concept, as in the following example:

Economics is the study of how people choose among the alternatives available to them. It’s the study of little choices (“Should I take the chocolate or the strawberry?”) and big choices (“Should we require a reduction in energy consumption in order to protect the environment?”). It’s the study of individual choices, choices by firms, and choices by governments. Life presents each of us with a wide range of alternative uses of our time and other resources; economists examine how we choose among those alternatives.

– Timothy Tregarthen, Economics

Example

One of the most common ways of developing a paragraph is by illustrating a point with one or more examples.

The Indians made names for us children in their teasing way. Because our very busy mother kept my hair cut short, like my brothers’, they called me Short Furred One, pointing to their hair and making the sign for short, the right hand with fingers pressed close together, held upward, back out, at the height intended. With me this was about two feet tall, the Indians laughing gently at my abashed face. I am told that I was given a pair of small moccasins that first time, to clear up my unhappiness at being picked out from the dusk behind the fire and my two unhappy shortcomings made conspicuous.

– Mari Sandoz, “The Go-Along Ones”

Division and classification

Division breaks a single item into parts. Classification groups many separate items according to their similarities. A paragraph evaluating one history course might divide the course into several segments—textbooks, lectures, assignments—and examine each one in turn. A paragraph giving an overview of many history courses might classify the courses in a number of ways—by time periods, by geographic areas, by the kinds of assignments demanded, by the number of students enrolled, or by some other principle.

DIVISION

We all listen to music according to our separate capacities. But, for the sake of analysis, the whole listening process may become clearer if we break it up into its component parts, so to speak. In a certain sense, we all listen to music on three separate planes. For lack of a better terminology, one might name these: (1) the sensuous plane, (2) the expressive plane, (3) the sheerly musical plane. The only advantage to be gained from mechanically splitting up the listening process into these hypothetical planes is the clearer view to be had of the way in which we listen.

– Aaron Copland, What to Listen For in Music

CLASSIFICATION

Two types of people are seduced by fad diets. Those who have always been overweight turn to them out of despair; they have tried everything, and yet nothing seems to work. A second group of people to succumb appear perfectly healthy but are baited by slogans such as “look good, feel good.” These slogans prompt self-questioning and insecurity—do I really look good and feel good?—and as a direct result, many healthy people fall prey to fad diets. With both types of people, however, the problems surrounding such diets are numerous and dangerous. In fact, these diets provide neither intelligent nor effective answers to weight control.

Comparison and contrast

When you compare two things, you look at their similarities; when you contrast two things, you focus on their differences. You can structure paragraphs that compare or contrast in two basic ways. One way is to present all the information about one item and then all the information about the other item, as in the following paragraph:

You could tell the veterans from the rookies by the way they were dressed. The knowledgeable ones had their heads covered by kerchiefs, so that if they were hired, tobacco dust wouldn’t get in their hair; they had on clean dresses that by now were faded and shapeless, so that if they were hired they wouldn’t get tobacco dust and grime on their best clothes. Those who were trying for the first time had their hair freshly done and wore attractive dresses; they wanted to make a good impression. But the dresses couldn’t be seen at the distance that many were standing from the employment office, and they were crumpled in the crush.

– Mary Mebane, “Summer Job”

Or you can switch back and forth between the two items, focusing on particular characteristics of each in turn.

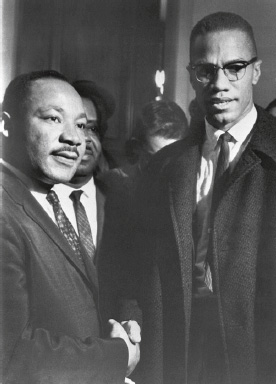

Malcolm X emphasized the use of violence in his movement and employed the biblical principle of “an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth.” King, on the other hand, felt that blacks should use nonviolent civil disobedience and employed the theme “turning the other cheek,” which Malcolm X rejected as “beggarly” and “feeble.” The philosophy of Malcolm X was one of revenge, and often it broke the unity of black Americans. More radical blacks supported him, while more conservative ones supported King. King thought that blacks should transcend their humanity. In contrast, Malcolm X thought they should embrace it and reserve their love for one another, regarding whites as “devils” and the “enemy.” The distance between Martin Luther King Jr.’s thinking and Malcolm X’s was the distance between growing up in the seminary and growing up on the streets, between the American dream and the American reality.

Analogy

Analogies (comparisons that explain an unfamiliar thing in terms of a familiar one) can also help develop paragraphs. In the following paragraph, the writer draws an unlikely analogy—between the human genome and Thanksgiving dinner—to help readers understand what scientists know about the human genome.

Think of the human genome as the ingredients list for a massive Thanksgiving dinner. Scientists long have had a general understanding of how the feast is cooked. They knew where the ovens were. Now, they also have a list of every ingredient. Yet much remains to be discovered. In most cases, no one knows exactly which ingredients are necessary for making, for example, the pumpkin pie as opposed to the cornbread. Indeed, many, if not most, of the recipes that use the genomic ingredients are missing, and there’s little understanding why small variations in the quality of the ingredients can “cook up” diseases in one person but not in another.

– USA Today, “Cracking of Life’s Genetic Code Carries Weighty Potential”

Cause and effect

You can often develop paragraphs by explaining the causes of something or the effects that something brings about. The following paragraph discusses how our desire for food that tastes good has affected history:

The human craving for flavor has been a largely unacknowledged and unexamined force in history. For millennia royal empires have been built, unexplored lands traversed, and great religions and philosophies changed by the spice trade. In 1492 Christopher Columbus set sail to find seasoning. Today the influence of flavor in the world marketplace is no less decisive. The rise and fall of corporate empires—of soft-drink companies, snack-food companies, and fast-food chains—is often determined by how their products taste.

– Eric Schlosser, Fast Food Nation

Process

Paragraphs that explain a process often use the principle of time or chronology to order the stages in the process.

By the late 20s, most people notice the first signs of aging in their physical appearance. Slight losses of elasticity in facial skin produce the first wrinkles, usually in those areas most involved in their characteristic facial expressions. As the skin continues to lose elasticity and fat deposits build up, the face sags a bit with age. Indeed, some people have drooping eyelids, sagging cheeks, and the hint of a double chin by age 40 (Whitbourne, 1985). Other parts of the body sag a bit as well, so as the years pass, adults need to exercise regularly if they want to maintain their muscle tone and body shape. Another harbinger of aging, the first gray hairs, is usually noticed in the 20s and can be explained by a reduction in the number of pigment-producing cells. Hair may become a bit less plentiful, too, because of hormonal changes and reduced blood supply to the skin.

– Kathleen Stassen Berger, The Developing Person through the Life Span

Problem and solution

Another way to develop a paragraph is to open with a topic sentence that states a problem or asks a question about a problem and then to offer a solution or answers in the sentences that follow—a technique used in this paragraph from a review of Ted Nordhaus and Michael Shellenberger’s book Break Through: From the Death of Environmentalism to the Politics of Possibility:

Unfortunately, at the moment growth means burning more fossil fuel…. How can that fact be faced? How to have growth that Americans want, but without limits that they instinctively oppose, and still reduce carbon emissions? [Nordhaus and Shellenberger’s] answer is: investments in new technology. Acknowledge that America “is great at imagining, experimenting, and inventing the future,” and then start spending. They cite examples ranging from the nuclear weapons program to the invention of the Internet to show what government money can do, and argue that too many clean-energy advocates focus on caps instead.

– Bill McKibben, “Can Anyone Stop It?”

Reiteration

Reiteration is a method of development you may recognize from political speeches or some styles of preaching. In this pattern, the writer states the main point of a paragraph and then restates it, hammering home the point and often building in intensity as well. In the following passage from Barack Obama’s 2004 speech at the Democratic National Convention, Obama contrasts what he identifies as the ideas of “those who are preparing to divide us” with memorable references to common ground and unity, including repeated references to the United States as he builds to his climactic point:

Now even as we speak, there are those who are preparing to divide us—the spin masters, the negative ad peddlers who embrace the politics of anything goes. Well, I say to them tonight, there is not a liberal America and a conservative America—there is the United States of America. There is not a black America and a white America and Latino America and an Asian America—there’s the United States of America. The pundits like to slice and dice our country into Red States and Blue States: Red States for Republicans, Blue States for Democrats. But I’ve got news for them, too. We worship an awesome God in the Blue States, and we don’t like federal agents poking around in our libraries in the Red States. We coach Little League in the Blue States and yes, we’ve got some gay friends in the Red States. There are patriots who opposed the war in Iraq and there are patriots who supported the war in Iraq. We are one people, all of us pledging allegiance to the stars and stripes, all of us defending the United States of America.

– Barack Obama