11.1 Stress and Illness

Sometimes we put ourselves in stressful situations. At other times, stress strikes without warning. Imagine being 21-

This chapter starts by taking a close look at stress and how it affects our health and well-

Stress: Some Basic Concepts

11-

stress the process by which we perceive and respond to certain events, called stressors, that we appraise as threatening or challenging.

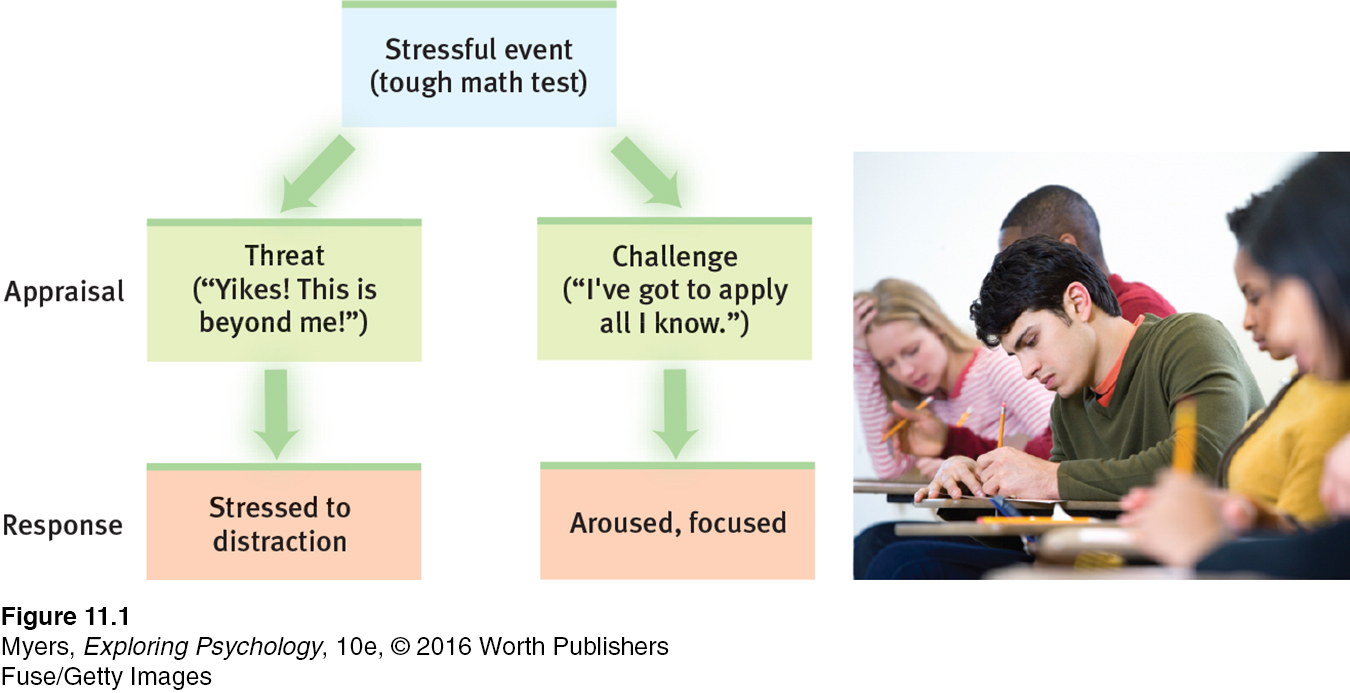

Psychologists define stress as the process of appraising and responding to a threatening or challenging event (FIGURE 11.1). But stress is a slippery concept. We sometimes use the word informally to describe threats or challenges (“Ben was under a lot of stress”), and at other times our responses (“Ben experienced acute stress”). To a psychologist, the dangerous truck ride was a stressor. Ben’s physical and emotional responses were a stress reaction. And the process by which he related to the threat was stress.

Stress arises less from events themselves than from how we appraise them (Lazarus, 1998). One person, alone in a house, ignores its creaking sounds and experiences no stress; someone else suspects an intruder and becomes alarmed. One person regards a new job as a welcome challenge; someone else appraises it as risking failure. When short-

“Too many parents make life hard for their children by trying, too zealously, to make it easy for them.”

German author Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-

But extreme or prolonged stress can harm us. Demanding jobs that mentally exhaust workers also can damage their physical health (Huang et al., 2010). Pregnant women with overactive stress systems tend to have shorter pregnancies, which pose health risks for their infants (Entringer et al., 2011).

So there is an interplay between our head and our health. Psychological states are physiological events that influence other parts of our physiological system. Just pausing to think about biting into an orange wedge—

Stressors—Things That Push Our Buttons

Stressors fall into three main types: catastrophes, significant life changes, and daily hassles. All can be toxic.

CATASTROPHES Catastrophes are unpredictable large-

For those who respond to catastrophes by relocating to another country, the stress may be twofold. The trauma of uprooting and family separation may combine with the challenges of adjusting to a new culture’s language, ethnicity, climate, and social norms (Pipher, 2002; Williams & Berry, 1991). In the first half-

SIGNIFICANT LIFE CHANGES Life transitions—

Some psychologists study the health effects of life changes by following people over time. Others compare the life changes recalled by those who have or have not suffered a specific health problem, such as a heart attack. In such studies, those recently widowed, fired, or divorced have been more vulnerable to disease (Dohrenwend et al., 1982; Strully, 2009). One Finnish study of 96,000 widowed people found that the survivor’s risk of death doubled in the week following a partner’s death (Kaprio et al., 1987). A cluster of crises—

DAILY HASSLES AND SOCIAL STRESS Events don’t have to remake our lives to cause stress. Stress also comes from daily hassles—

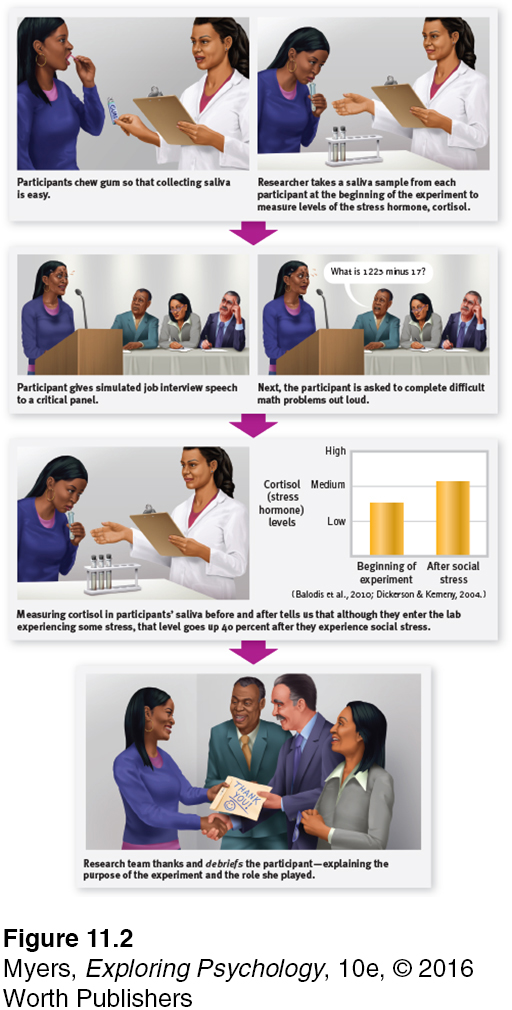

Many people face more significant daily hassles. As the Great Recession of 2008–

Daily economic pressures may be compounded by prejudice against our gender identity, sexual orientation, or race, which—

The Stress Response System

Medical interest in stress dates back to Hippocrates (460–

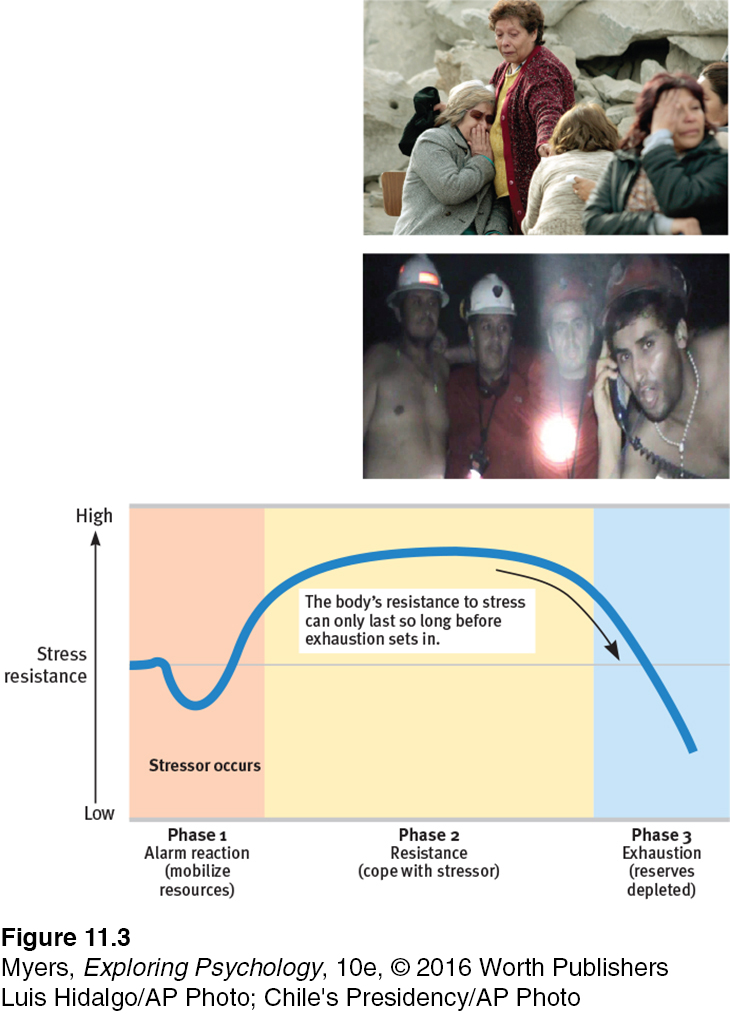

general adaptation syndrome (GAS) Selye’s concept of the body’s adaptive response to stress in three phases—

Canadian scientist Hans Selye’s (1936, 1976) 40 years of research on stress extended Cannon’s findings. His studies of animals’ reactions to various stressors, such as electric shock and surgery, helped make stress a major concept in both psychology and medicine. Selye proposed that the body’s adaptive response to stress is so general that, like a single burglar alarm, it sounds, no matter what intrudes. He named this response the general adaptation syndrome (GAS), and he saw it as a three-

In Phase 1, you have an alarm reaction, as your sympathetic nervous system is suddenly activated. Your heart rate zooms. Blood is diverted to your skeletal muscles. You feel the faintness of shock. With your resources mobilized, you are now ready to fight back.

During Phase 2, resistance, your temperature, blood pressure, and respiration remain high. Your adrenal glands pump hormones into your bloodstream. You are fully engaged, summoning all your resources to meet the challenge. As time passes, with no relief from stress, your body’s reserves dwindle.

You have reached Phase 3, exhaustion. With exhaustion, you become more vulnerable to illness or even, in extreme cases, collapse and death.

Selye’s basic point: Although the human body copes well with temporary stress, prolonged stress can damage it. Severe childhood stress, such as from abuse, gets under the skin, leading to greater stress responses and disease risk (Hanson et al., 2015; Miller et al., 2011). Even fearful, stressed rats have been found to die sooner, after about 600 days, than their more confident siblings, which average 700-

tend and befriend under stress, people (especially women) often provide support to others (tend) and bond with and seek support from others (befriend).

There are other ways to deal with stress. One option is a common response to a loved one’s death: Withdraw. Pull back. Conserve energy. Faced with an extreme disaster, such as a ship sinking, some people become paralyzed by fear. Another option (often found among women) is to give and seek support—

Facing stress, men more often than women tend to withdraw socially, turn to alcohol, or become aggressive. Women more often respond to stress by nurturing and banding together. This may in part be due to oxytocin, a stress-

It often pays to spend our resources in fighting or fleeing an external threat. But we do so at a cost. When stress is momentary, the cost is small. When stress persists, the cost may be much higher, in the form of lowered resistance to infections and other threats to mental and physical well-

“You’ve got to know when to hold ’em; know when to fold ’em. Know when to walk away, and know when to run.”

Kenny Rogers, “The Gambler,” 1978

RETRIEVE IT

Question

The stress response system: When alerted to a negative, uncontrollable event, our nervous system arouses us. Heart rate and respiration (increase/decrease). Blood is diverted from digestion to the skeletal . The body releases sugar and fat. All this prepares the body for the response.

Stress and Vulnerability to Disease

11-

health psychology a subfield of psychology that provides psychology’s contribution to behavioral medicine.

psychoneuroimmunology the study of how psychological, neural, and endocrine processes together affect the immune system and resulting health.

To study how stress and healthy and unhealthy behaviors influence health and illness, psychologists and physicians have created the interdisciplinary field of behavioral medicine, integrating behavioral and medical knowledge. One subfield, health psychology, provides psychology’s contribution to behavioral medicine. A branch of health psychology called psychoneuroimmunology focuses on mind-

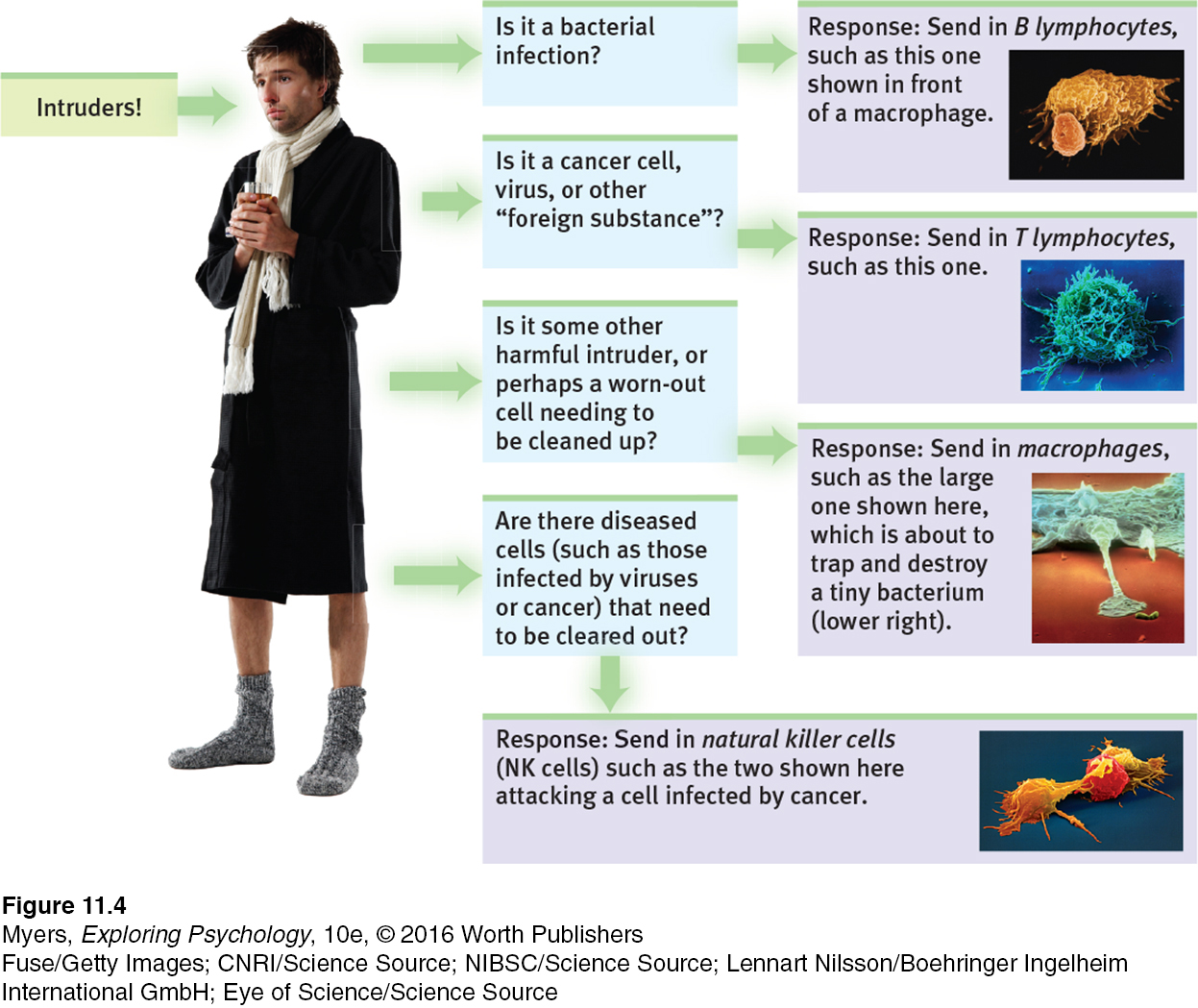

If you’ve ever had a stress headache, or felt your blood pressure rise with anger, you don’t need to be convinced that our psychological states have physiological effects. Stress can even leave you less able to fight off disease because your nervous and endocrine systems influence your immune system (Sternberg, 2009). You can think of your immune system as a complex surveillance system. When it functions properly, it keeps you healthy by isolating and destroying bacteria, viruses, and other invaders. Four types of cells are active in these search-

B lymphocytes (white blood cells) mature in the bone marrow and release antibodies that fight bacterial infections.

T lymphocytes (white blood cells) mature in the thymus and other lymphatic tissue and attack cancer cells, viruses, and foreign substances.

Macrophages (“big eaters”) identify, pursue, and ingest harmful invaders and worn-

out cells. Natural killer cells (NK cells) pursue diseased cells (such as those infected by viruses or cancer).

Your age, nutrition, genetics, body temperature, and stress all influence your immune system’s activity. If it doesn’t function properly, your immune system can err in two directions:

Responding too strongly, the immune system may attack the body’s own tissues, causing an allergic reaction or a self-

attacking disease such as lupus, multiple sclerosis, or some forms of arthritis. Women, who are immunologically stronger than men, are more susceptible to self- attacking diseases (Nussinovitch & Schoenfeld, 2012; Schwartzman- Morris & Putterman, 2012). Underreacting, the immune system may allow a bacterial infection to flare, a dormant virus to erupt, or cancer cells to multiply. To protect transplanted organs, which the recipient’s immune system would view as a foreign body, surgeons may deliberately suppress the patient’s immune system.

Stress can also trigger immune suppression by reducing the release of disease-

Human immune systems react similarly. Some examples:

Surgical wounds heal more slowly in stressed people. In one experiment, dental students received punch wounds (precise small holes punched in the skin). Compared with wounds placed during summer vacation, those placed three days before a major exam healed 40 percent more slowly (Kiecolt-

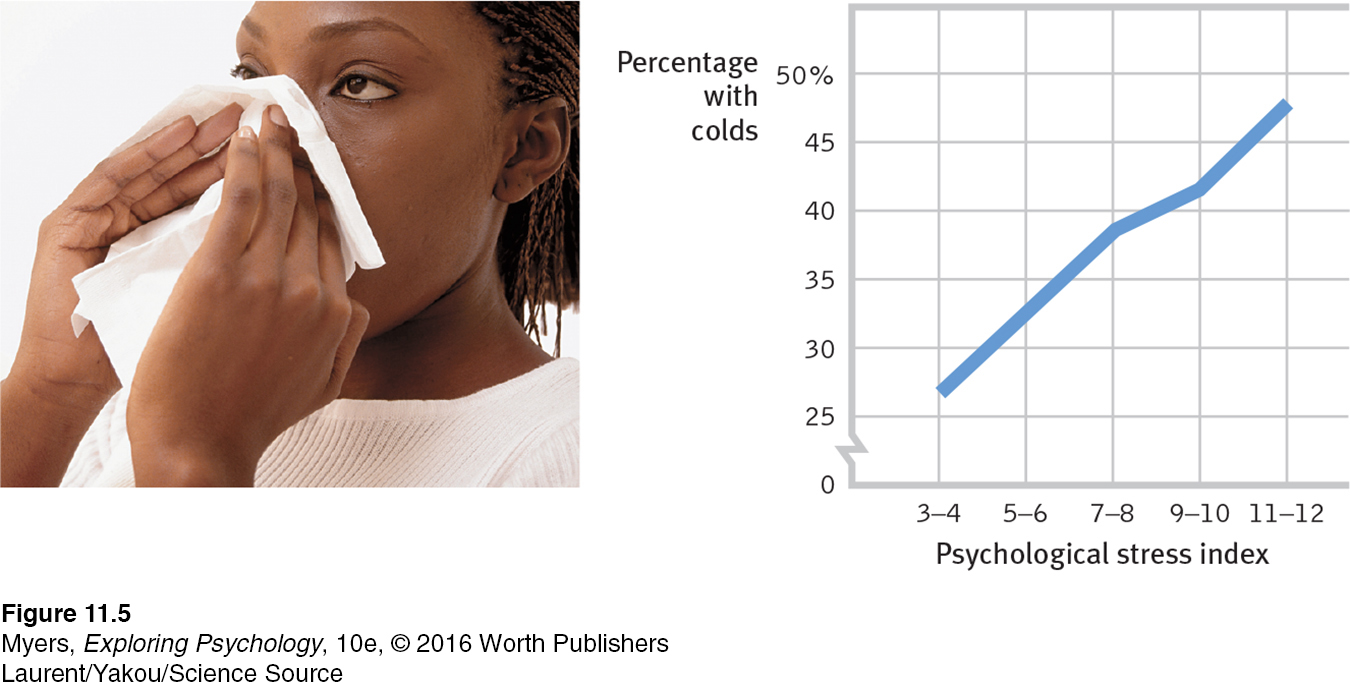

Glaser et al., 1998). In other studies, marriage conflict has also slowed punch- wound healing (Kiecolt- Glaser et al., 2005). Page 412Stressed people are more vulnerable to colds. Major life stress increases the risk of a respiratory infection (Pedersen et al., 2010). When researchers dropped a cold virus into the noses of stressed and relatively unstressed people, 47 percent of those living stress-

filled lives developed colds (FIGURE 11.5). Among those living relatively free of stress, only 27 percent did. In follow- up research, the happiest and most relaxed people were likewise markedly less vulnerable to an experimentally delivered cold virus (Cohen et al., 2003, 2006; Cohen & Pressman, 2006). Vaccine effectiveness declines with stress. Nurses gave older adults a flu vaccine and then measured how well their bodies fought off bacteria and viruses. The vaccine was most effective among those who reported experiencing low stress (Segerstrom et al., 2012).

The stress effect on immunity makes physiological sense. It takes energy to track down invaders, produce swelling, and maintain fevers. Thus, when diseased, your body reduces its muscular energy output by decreasing activity and increasing sleep. Stress does the opposite. It creates a competing energy need. During an aroused fight-

RETRIEVE IT

Question

The field of studies mind-body interactions, including the effects of psychological, neural, and endocrine functioning on the immune system and overall health.

Question

What general effect does stress have on our overall health?

Stress and AIDS

We know that stress suppresses immune system functioning. What does this mean for people with AIDS (acquired immune deficiency syndrome)? As its name tells us, AIDS is an immune disorder, caused by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Although AIDS-related deaths have decreased 35 percent since 2005, AIDS remains the world’s sixth leading cause of death and Africa’s number one killer (UNAIDS, 2014; WHO, 2013). Worldwide, some 2.1 million people—

Stress cannot give people AIDS. But could stress and negative emotions speed the transition from HIV infection to AIDS? And might stress predict a faster decline in those with AIDS? An analysis of 33,252 participants from around the world suggests the answer to both questions is Yes (Chida & Vedhata, 2009). The greater the stress that HIV-infected people experience, the faster their disease progresses.

Would efforts to reduce stress help control the disease? Again, the answer appears to be Yes. Educational initiatives, bereavement support groups, cognitive therapy, relaxation training, and exercise programs that reduce distress have all had positive consequences for HIV-

Stress and Cancer

Stress does not create cancer cells. But in a healthy, functioning immune system, lymphocytes, macrophages, and NK cells search out and destroy cancer cells and cancer-

“I didn’t give myself cancer.”

Mayor Barbara Boggs Sigmund (1939-

Does this stress-

When organic causes of illness are unknown, it is tempting to invent psychological explanations. Before the germ that causes tuberculosis was discovered, personality explanations of TB were popular (Sontag, 1978).

One danger in hyping reports on emotions and cancer is that some patients may then blame themselves for their illness: “If only I had been more expressive, relaxed, and hopeful.” A corollary danger is a “wellness macho” among the healthy, who take credit for their “healthy character” and lay a guilt trip on the ill: “She has cancer? That’s what you get for holding your feelings in and being so nice.” Dying thus becomes the ultimate failure.

For a 7-

For a 7-

It’s important enough to repeat: Stress does not create cancer cells. At worst, it may affect their growth by weakening the body’s natural defenses against multiplying malignant cells (Lutgendorf et al., 2008; Nausheen et al., 2010; Sood et al., 2010). Although a relaxed, hopeful state may enhance these defenses, we should be aware of the thin line that divides science from wishful thinking. The powerful biological processes at work in advanced cancer or AIDS are not likely to be completely derailed by avoiding stress or maintaining a relaxed but determined spirit (Anderson, 2002; Kessler et al., 1991). And that explains why research consistently indicates that psychotherapy does not extend cancer patients’ survival (Coyne et al., 2007, 2009; Coyne & Tennen, 2010).

Stress and Heart Disease

11-

Depart from reality for a moment. In this new world, you wake up each day, eat your breakfast, and check the news. Four 747 jumbo jet airplanes crashed yesterday and all 1642 passengers died. You finish your breakfast, grab your things, and head to class. It’s just an average day.

coronary heart disease the clogging of the vessels that nourish the heart muscle; the leading cause of death in many developed countries.

Replace airline crashes with coronary heart disease, the United States’ leading cause of death, and you have reentered reality. About 610,000 Americans die annually from heart disease (CDC, 2015). High blood pressure and a family history of the disease increase the risk. So do smoking, obesity, physical inactivity, and a high cholesterol level.

Stress and personality also play a big role in heart disease. The more psychological trauma people experience, the more their bodies generate inflammation, which is associated with heart and other health problems (O’Donovan et al., 2012). Plucking a hair and measuring its level of cortisol (a stress hormone) can help predict whether a child has experienced prolonged stress or an adult will have a future heart attack (Karlén et al., 2015; Pereg et al., 2011).

TYPE A PERSONALITY In a classic study, Meyer Friedman, Ray Rosenman, and their colleagues tested the idea that stress increases heart disease risk by measuring the blood cholesterol level and clotting speed of 40 U.S. male tax accountants at different times of year (Friedman & Ulmer, 1984). From January through March, the test results were completely normal. Then, as the accountants began scrambling to finish their clients’ tax returns before the April 15 filing deadline, their cholesterol and clotting measures rose to dangerous levels. In May and June, with the deadline past, the measures returned to normal. For these men, stress predicted heart attack risk. Blood pressure also rises as students approach stressful exams (Conley & Lehman, 2012).

Type A Friedman and Rosenman’s term for competitive, hard-

Type B Friedman and Rosenman’s term for easygoing, relaxed people.

See LaunchPad’s Video: Longitudinal and Cross-

See LaunchPad’s Video: Longitudinal and Cross-

So, are some of us at high risk of stress-

Nine years later, 257 men had suffered heart attacks, and 69 percent of them were Type A. Moreover, not one of the “pure” Type Bs—

In both India and America, Type A bus drivers are literally hard-

As often happens in science, this exciting discovery provoked enormous public interest. After that initial honeymoon period, researchers wanted to know more. Was the finding reliable? If so, what was the toxic component of the Type A profile: Time-

More than 700 studies have now explored possible psychological correlates or predictors of cardiovascular health (Chida & Hamer, 2008; Chida & Steptoe, 2009). These reveal that Type A’s toxic core is negative emotions—

“The fire you kindle for your enemy often burns you more than him.”

Chinese proverb

Hundreds of other studies of young and middle-

TYPE D PERSONALITY In recent years, another personality type has interested stress and heart disease researchers. Type A individuals direct their negative emotion toward dominating others. People with another personality type—

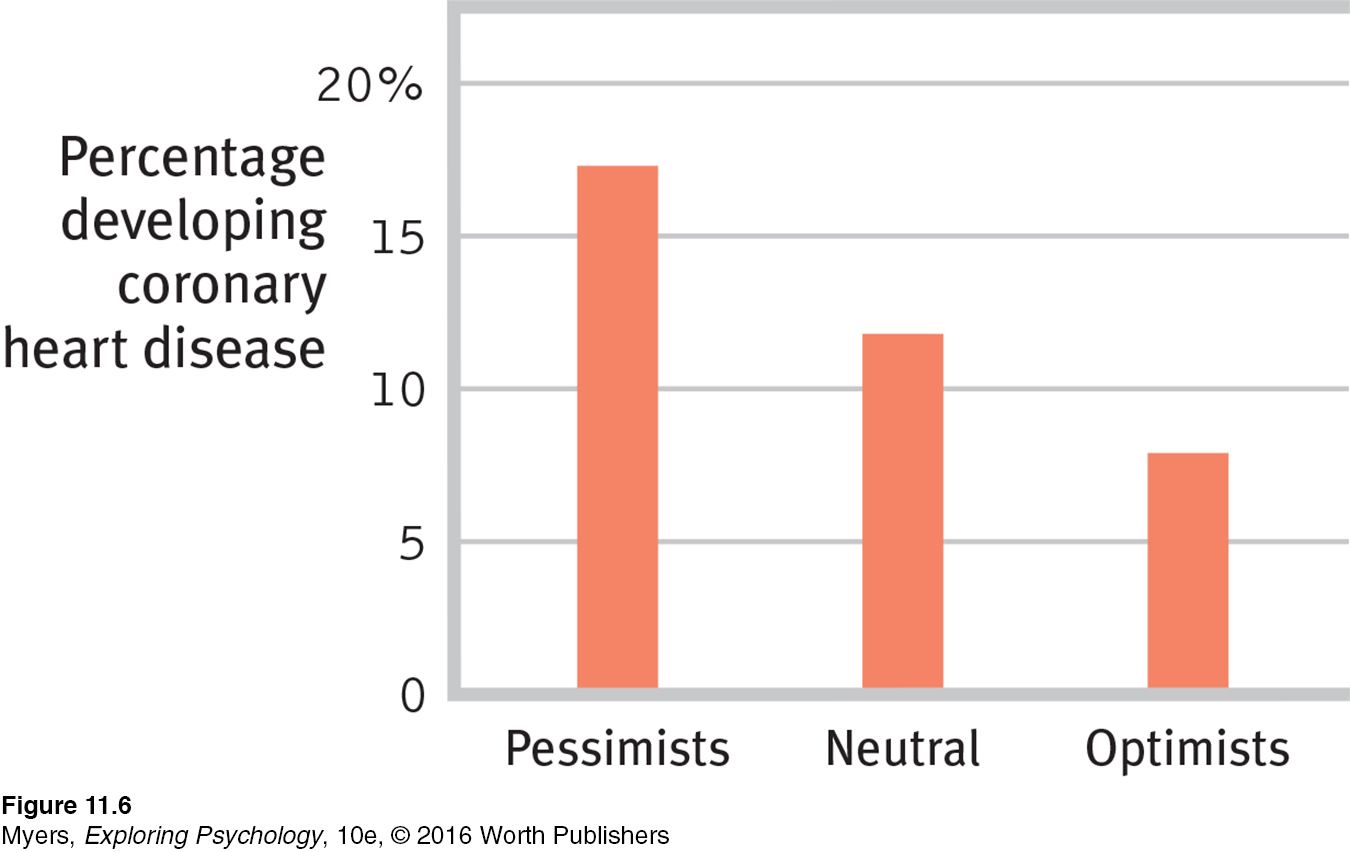

EFFECTS OF PESSIMISM AND DEPRESSION Pessimism seems to be similarly toxic. Laura Kubzansky and her colleagues (2001) studied 1306 initially healthy men who a decade earlier had scored as optimists, pessimists, or neither. Even after other risk factors such as smoking had been ruled out, pessimists were more than twice as likely as optimists to develop coronary heart disease (FIGURE 11.6). Happy people tend to be healthier and to outlive their unhappy peers (Diener & Chan, 2011; Siahpush et al., 2008). Even a big, happy smile predicts longevity, as researchers discovered when they examined the photographs of 150 Major League Baseball players who had appeared in the 1952 Baseball Register and had died by 2009 (Abel & Kruger, 2010). On average, the nonsmilers had died at 73, compared with an average 80 years for those with a broad, genuine smile. People with broad smiles tend to have extensive social networks, which predict longer life (Hertenstein, 2009).

“A cheerful heart is a good medicine, but a downcast spirit dries up the bones.”

Proverbs 17:22

IMMERSIVE LEARNING To consider how researchers have studied these issues, visit LaunchPad’s How Would You Know If Stress Increases Risk of Disease?

IMMERSIVE LEARNING To consider how researchers have studied these issues, visit LaunchPad’s How Would You Know If Stress Increases Risk of Disease?

Depression, too, can be lethal. The accumulated evidence suggests that “depression substantially increases the risk of death, especially death by unnatural causes and cardiovascular disease” (Wulsin et al., 1999). In one study, nearly 4000 English adults (ages 52 to 79) provided mood reports from a single day. Compared with those in a good mood on that day, those in a blue mood were twice as likely to be dead five years later (Steptoe & Wardle, 2011). After following 63,469 women over a dozen years, researchers found more than a doubled rate of heart attack death among those who initially scored as depressed (Whang et al., 2009). In the years following a heart attack, people with high depression scores were four times more likely than their low-

THINKING CRITICALLY ABOUT

Anger Management

11-

When we face a threat or challenge, fear triggers flight but anger triggers fight—

Individualist cultures encourage people to vent their rage. Such advice is seldom heard in cultures where people’s identity is centered more on the group. People who keenly sense their interdependence see anger as a threat to group harmony (Markus & Kitayama, 1991). In Tahiti, for instance, people learn to be considerate and gentle. In Japan, from infancy on, angry expressions are less common than in Western cultures, where in recent politics, anger seems all the rage.

catharsis in psychology, the idea that “releasing” aggressive energy (through action or fantasy) relieves aggressive urges.

The Western vent-

However, catharsis usually fails to cleanse our rage. More often, expressing anger breeds more anger. For one thing, it may provoke further retaliation, causing a minor conflict to escalate into a major confrontation. For another, expressing anger can magnify anger. As behavior feedback research indicates, acting angry can make us feel angrier (Flack, 2006; Snodgrass et al., 1986). In one study, people who had been provoked were asked to wallop a punching bag while ruminating about the person who had angered them. Later, when given a chance for revenge, they became even more aggressive (Bushman, 2002).

Angry outbursts that temporarily calm us may also become reinforcing and therefore habit forming. If stressed managers find they can drain off some of their tension by berating an employee, then the next time they feel irritated and tense they may be more likely to explode again.

What are some better ways to manage anger? Experts offer three suggestions:

Wait. You can reduce the level of physiological arousal of anger by waiting. “It is true of the body as of arrows,” noted Carol Tavris (1982), “what goes up must come down. Any emotional arousal will simmer down if you just wait long enough.”

Find a healthy distraction or support. Calm yourself by exercising, playing an instrument, or talking it through with a friend. Brain scans show that ruminating inwardly about why you are angry serves only to increase amygdala bloodflow (Fabiansson et al., 2012).

Distance yourself. Try to move away from the situation mentally, as if you are watching it unfold from a distance. Self-

distancing reduces rumination, anger, and aggression (Kross & Ayduk, 2011; Mischkowski et al., 2012; White et al., 2015).

Anger is not always wrong. Used wisely, it can communicate strength and competence (Tiedens, 2001). Anger also motivates people to take action and achieve goals (Aarts & Custers, 2012). Controlled expressions of anger are more adaptive than either hostile outbursts or pent-

What if someone’s behavior really hurts you, and you cannot resolve the conflict? Research commends the age-

“Venting to reduce anger is like using gasoline to put out a fire.”

Researcher Brad Bushman (2002)

“Anger will never disappear so long as thoughts of resentment are cherished in the mind.”

The Buddha, 500 B.C.E.

RETRIEVE IT

Question

Which one of the following is an effective strategy for reducing angry feelings?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

STRESS AND INFLAMMATION Depressed people tend to smoke more and exercise less (Whooley et al., 2008), but stress itself is also disheartening:

When following 17,415 middle-

aged American women, researchers found an 88 percent increased risk of heart attacks among those facing significant work stress (Slopen et al., 2010). In Denmark, a study of 12,116 female nurses found that those reporting “much too high” work pressures had a 40 percent increased risk of heart disease (Allesøe et al., 2010).

In the United States, a 10-

year study of middle- aged workers found that involuntary job loss more than doubled their risk of a heart attack (Gallo et al., 2006).

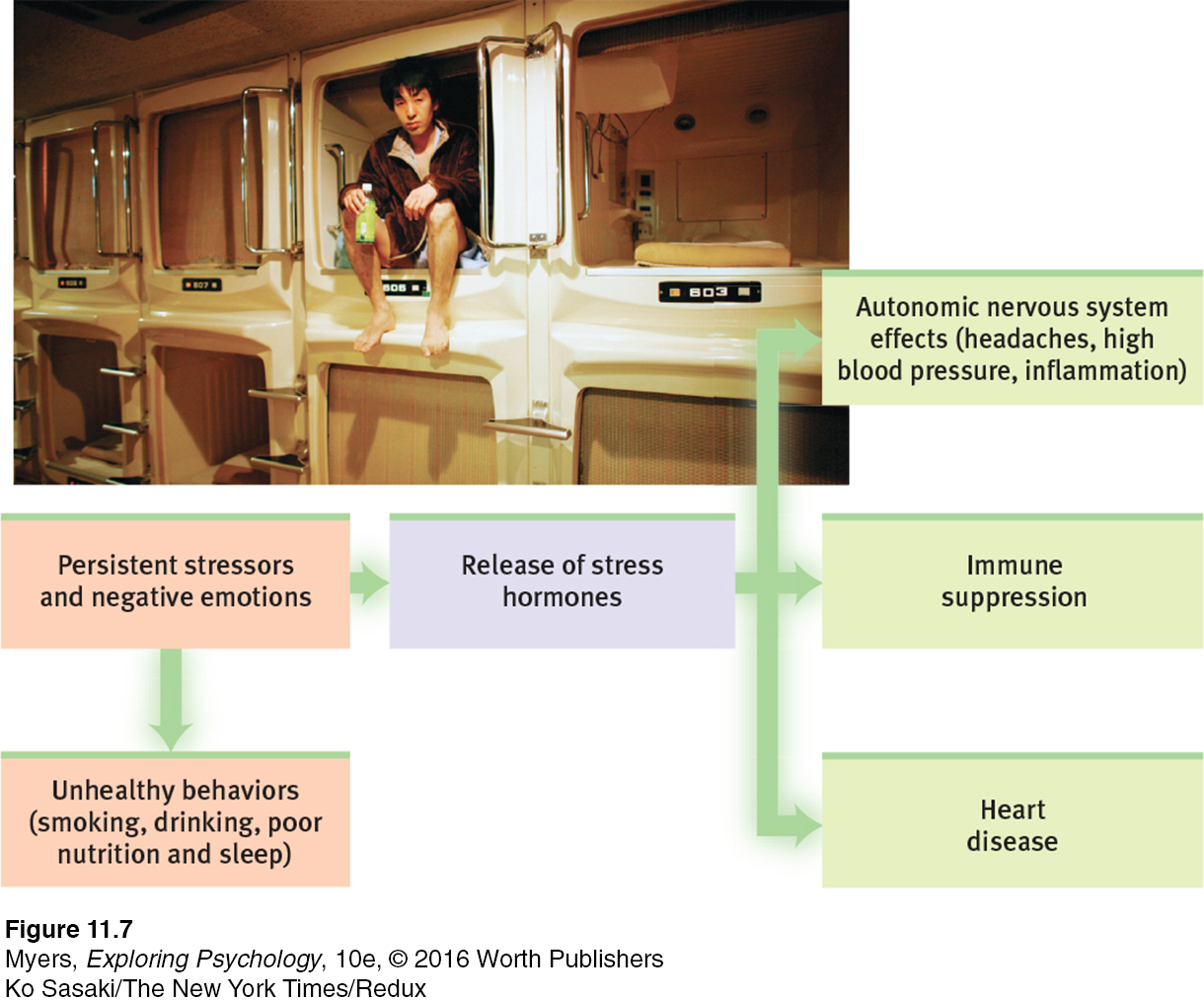

Both heart disease and depression may result when stress triggers blood vessel inflammation (Matthews, 2005; Miller & Blackwell, 2006). As the body focuses its energies on fleeing or fighting a threat, stress hormones boost the production of proteins that contribute to inflammation. Persistent inflammation can lead to asthma or clogged arteries and can worsen depression.

We can view the stress effect on our disease resistance as a price we pay for the benefits of stress (FIGURE 11.7). Stress invigorates our lives by arousing and motivating us. An unstressed life would hardly be challenging or productive.

* * *

Traditionally, people have thought about their health only when something goes wrong—

RETRIEVE IT

Question

Which component of the Type A personality has been linked most closely to coronary heart disease?

Question

How does Type D personality differ from Type A?

REVIEW Stress and Illness

Learning Objectives

Test Yourself by taking a moment to answer each of these Learning Objective Questions (repeated here from within the chapter). Research suggests that trying to answer these questions on your own will improve your long-

Question

11-

Question

11-

Question

11-

Question

11-

Terms and Concepts to Remember

Test yourself on these terms.

Question

stress (p. 406) general adaptation syndrome (GAS) (p. 409) tend and befriend (p. 410) health psychology (p. 410) psychoneuroimmunology (p. 410) coronary heart disease (p. 414) Type A (p. 414) Type B (p. 414) catharsis (p. 416) | the process by which we perceive and respond to certain events, called stressors, that we appraise as threatening or challenging. under stress, people (especially women) often provide support to others (tend) and bond with and seek support from others (befriend). the study of how psychological, neural, and endocrine processes together affect the immune system and resulting health. Friedman and Rosenman's term for easygoing, relaxed people. the clogging of the vessels that nourish the heart muscle; the leading cause of death in many developed countries. in psychology, the idea that "releasing" aggressive energy (through action or fantasy) relieves aggressive urges. Friedman and Rosenman's term for competitive, hard-driving, impatient, verbally aggressive, and anger-prone people. a subfield of psychology that provides psychology's contribution to behavioral medicine. Selye's concept of the body's adaptive response to stress in three phases— |

Experience the Testing Effect

Test yourself repeatedly throughout your studies. This will not only help you figure out what you know and don’t know; the testing itself will help you learn and remember the information more effectively thanks to the testing effect.

Question 11.1

1. Selye's general adaptation syndrome (GAS) consists of an alarm reaction followed by , then .

Question 11.2

2. When faced with stress, women are more likely than men to experience the -and- response.

Question 11.3

3. The number of short-term illnesses and stress-related psychological disorders was higher than usual in the months following an earthquake. Such findings suggest that

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 11.4

4. Which of the following is NOT one of the three main types of stressors?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 11.5

5. Stress can suppress the immune system by prompting a decrease in the release of , the immune cells that ordinarily attack bacteria, viruses, cancer cells, and other foreign substances.

Question 11.6

6. Research has shown that people are at increased risk for cancer a year or so after experiencing depression, helplessness, or bereavement. In describing this link, researchers are quick to point out that

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 11.7

7. A Chinese proverb warns, “The fire you kindle for your enemy often burns you more than him.” How is this true of Type A individuals?

Use  to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in

to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in  .

.