11.2 Health and Happiness

Coping With Stress

11-

coping alleviating stress using emotional, cognitive, or behavioral methods.

Stressors are unavoidable. This fact, coupled with the fact that persistent stress correlates with heart disease, depression, and lowered immunity, gives us a clear message: We need to learn to cope with the stress in our lives, alleviating it with emotional, cognitive, or behavioral methods.

problem-focused coping attempting to alleviate stress directly—

emotion-focused coping attempting to alleviate stress by avoiding or ignoring a stressor and attending to emotional needs related to our stress reaction.

Some stressors we address directly, with problem-focused coping. If our impatience leads to a family fight, we may go directly to that family member to work things out. We tend to use problem-

When challenged, some of us tend to respond with problem-

Personal Control

11-

Picture the scene: Two rats receive simultaneous shocks. One can turn a wheel to stop the shocks. The helpless rat, but not the wheel turner, becomes more susceptible to ulcers and lowered immunity to disease (Laudenslager & Reite, 1984). In humans, too, uncontrollable threats trigger the strongest stress responses (Dickerson & Kemeny, 2004).

learned helplessness the hopelessness and passive resignation an animal or person learns when unable to avoid repeated aversive events.

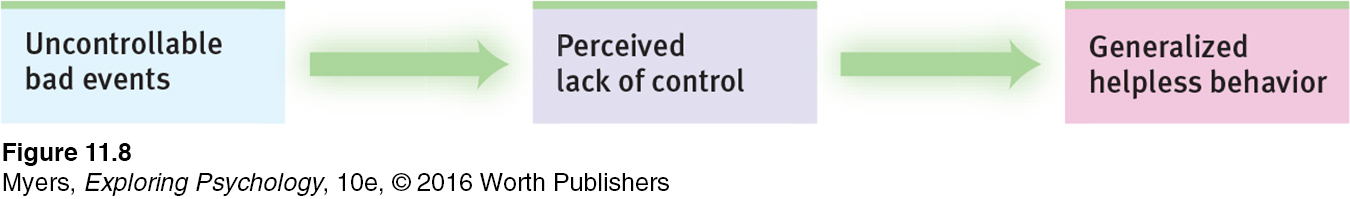

At times, we all feel helpless, hopeless, and depressed after experiencing a series of bad events beyond our control. Martin Seligman and his colleagues have shown that for some animals and people, a series of uncontrollable events creates a state of learned helplessness, with feelings of passive resignation (FIGURE 11.8 below). In one series of experiments, dogs were strapped in a harness and given repeated shocks, with no opportunity to avoid them (Seligman & Maier, 1967). Later, when placed in another situation where they could escape the punishment by simply leaping a hurdle, the dogs cowered as if without hope. Other dogs that had been able to escape the first shocks reacted differently. They had learned they were in control and easily escaped the shocks in the new situation (Seligman & Maier, 1967). In other experiments, people have shown similar patterns of learned helplessness (Abramson et al., 1978, 1989; Seligman, 1975).

Perceiving a loss of control, we become more vulnerable to ill health. A famous study of elderly nursing home residents with little perceived control over their activities found that they declined faster and died sooner than those given more control (Rodin, 1986). Workers able to adjust office furnishings and control interruptions and distractions in their work environment have experienced less stress (O’Neill, 1993). Such findings may help explain why British executives have tended to outlive those in clerical or laboring positions, and why Finnish workers with low job stress have been less than half as likely to die of stroke or heart disease as those with a demanding job and little control. The more control workers have, the longer they live (Bosma et al., 1997, 1998; Kivimaki et al., 2002; Marmot et al., 1997).

Increasing control—

Control also helps explain a link between economic status and longevity (Jokela et al., 2009). In one study of 843 grave markers in an old cemetery in Glasgow, Scotland, those with the costliest, highest pillars (indicating the most affluence) tended to have lived the longest (Carroll et al., 1994). Likewise, American presidents, who are generally wealthy and well-

Why does perceived loss of control predict health problems? Because losing control provokes an outpouring of stress hormones. When rats cannot control shock or when humans or other primates feel unable to control their environment, stress hormone levels rise, blood pressure increases, and immune responses drop (Rodin, 1986; Sapolsky, 2005). Captive animals experience more stress and are more vulnerable to disease than their wild counterparts (Roberts, 1988). Human studies confirm that stress increases when we lack control. The greater nurses’ workload, the higher their cortisol level and blood pressure—

INTERNAL VERSUS EXTERNAL LOCUS OF CONTROL If experiencing a loss of control can be stressful and unhealthy, do people who generally perceive they have control of their lives enjoy better health? Consider your own perceptions of control. Do you believe that your life is beyond your control? That getting a good job depends mainly on being in the right place at the right time? Or do you more strongly believe that you control your own fate? That being a success is a matter of hard work? Did your parents influence your feelings of control? Did your culture?

external locus of control the perception that chance or outside forces beyond our personal control determine our fate.

internal locus of control the perception that we control our own fate.

Hundreds of studies have compared people who differ in their perceptions of control. On one side are those who have what psychologist Julian Rotter called an external locus of control—the perception that chance or outside forces control their fate. On the other side are those who perceive an internal locus of control, who believe they control their own destiny. In study after study, the “internals” have achieved more in school and work, acted more independently, enjoyed better health, and felt less depressed than did the “externals” (Lefcourt, 1982; Ng et al., 2006). In one long-

Another way to say that we believe we are in control of our own life is to say we have free will, or that we control our own willpower. Studies show that people who believe in their freedom learn better, perform better at work, behave more helpfully, and have a stronger desire to punish rule breakers (Clark et al., 2014; Job et al., 2010; Stillman et al., 2010).

Compared with their parents’ generation, more young Americans now express an external locus of control (Twenge et al., 2004). This shift may help explain an associated increase in rates of depression and other psychological disorders in young people (Twenge et al., 2010).

RETRIEVE IT

Question

To cope with stress when we feel in control of our world, we tend to use -focused (emotion/problem) strategies. To cope with stress when we believe we cannot change a situation, we tend to use -focused (emotion/problem) strategies.

DEPLETING AND STRENGTHENING SELF-

11-

self-control the ability to control impulses and delay short-

Self-control is the ability to control impulses and delay short-

Self-

Exercising willpower decreases neural activation in brain regions associated with mental control (Wagner et al., 2013). Might sugar provide a sweet solution to self-

Researchers do not encourage candy bar diets to improve self-

The decreased mental energy after exercising self-

The point to remember: Develop self-

Explanatory Style: Optimism Versus Pessimism

11-

In The How of Happiness, social psychologist Sonja Lyubomirsky (2008) tells the true story of Randy, who has lived a hard life. His dad and best friend both died by suicide. Growing up, his mother’s boyfriend treated him poorly. Randy’s first wife was unfaithful, and they divorced. Despite these misfortunes, Randy has a sunny disposition. He remarried and enjoys being the stepfather to three boys. His work is rewarding. Randy says he survived his life challenges by seeing the “silver lining in the cloud.”

Randy’s story illustrates how our outlook—

Optimistic students have also tended to get better grades because they often respond to setbacks with the hopeful attitude that effort, good study habits, and self-

Consider the consistency and startling magnitude of the optimism and positive emotions factor in several other studies:

When Finnish researchers followed 2428 men for up to a decade, the number of deaths among those with a bleak, hopeless outlook was more than double that found among their optimistic counterparts (Everson et al., 1996). American researchers found the same when following 4256 Vietnam-

era veterans (Phillips et al., 2009). A now-

famous study followed up on 180 Catholic nuns who had written brief autobiographies at about 22 years of age and had thereafter lived similar lifestyles. Those who had expressed happiness, love, and other positive feelings in their autobiographies lived an average 7 years longer than their more dour counterparts (Danner et al., 2001). By age 80, some 54 percent of those expressing few positive emotions had died, as had only 24 percent of the most positive spirited. Optimists not only live long lives, but they maintain a positive view as they approach the end of their lives. One study followed more than 68,000 American women, ages 50 to 79 years, for nearly two decades (Zaslavsky et al., 2015). As death grew nearer, the optimistic women tended to feel more life satisfaction than did the pessimistic women.

“The optimist proclaims we live in the best of all possible worlds; and the pessimist fears this is true.”

James Branch Cabell, The Silver Stallion, 1926

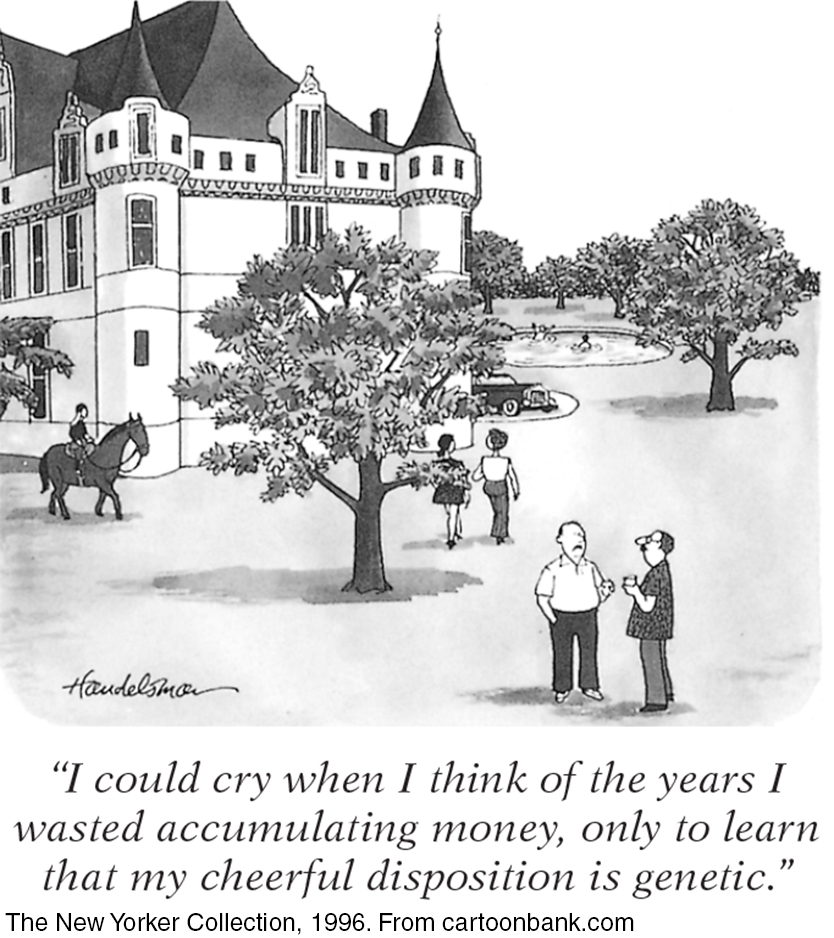

Optimism runs in families, so some people truly are born with a sunny, hopeful outlook. With identical twins, if one is optimistic, the other often will be as well (Bates, 2015; Mosing et al., 2009). One genetic marker of optimism is a gene that enhances the social-

The good news is that all of us, even the most pessimistic, can learn to become more optimistic. Compared with a control group of pessimists who simply kept diaries of their daily activities, pessimists in a skill-

Social Support

11-

Social support—

Close relationships have also predicted health. People are less likely to die early if supported by close relationships (Shor et al., 2013; Uchino, 2009). When Brigham Young University researchers combined data from 70 studies of 3.4 million people worldwide, they confirmed a striking effect of social support (Holt-

To combat social isolation, we need to do more than collect lots of acquaintances. We need people who genuinely care about us (Cacioppo et al., 2014; Hawkley et al., 2008). Some fill this need by connecting with friends, family, co-

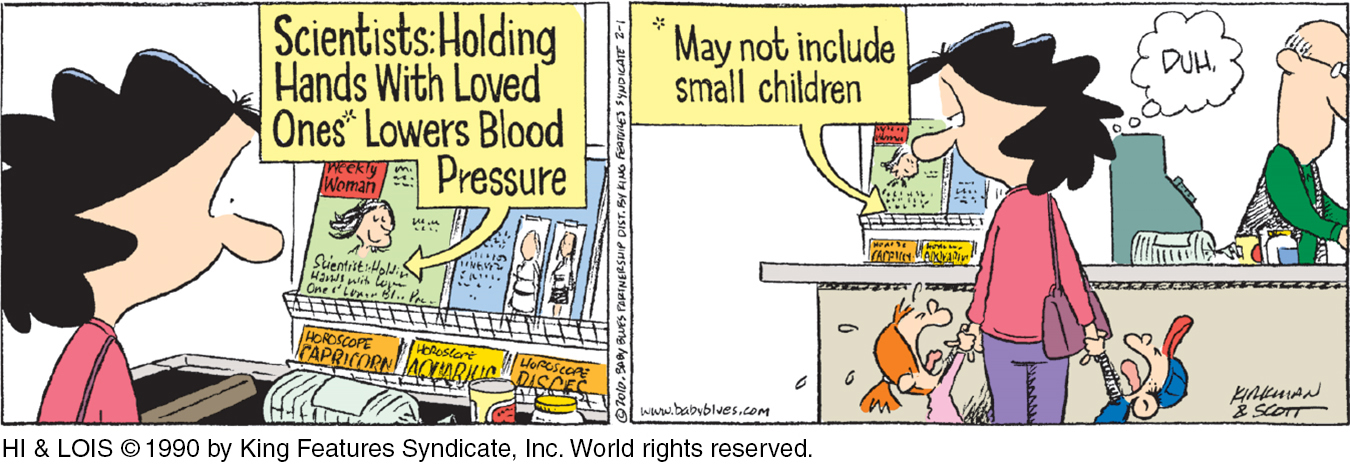

What explains the link between social support and health? Are middle-

Social support calms us and reduces blood pressure and stress hormones. Numerous studies support this finding (Hostinar et al., 2014; Uchino et al., 1996, 1999). To see if social support might calm people’s response to threats, one research team subjected happily married women, while lying in an fMRI machine, to the threat of electric shock to an ankle (Coan et al., 2006). During the experiment, some women held their husband’s hand. Others held the hand of an unknown person or no hand at all. While awaiting the occasional shocks, women holding their husband’s hand showed less activity in threat-

Social support fosters stronger immune functioning. Volunteers in studies of resistance to cold viruses showed this benefit (Cohen et al., 1997, 2004). Healthy volunteers inhaled nasal drops laden with a cold virus and were quarantined and observed for five days. (In these experiments, more than 600 volunteers received $800 each to endure this experience.) Age, race, sex, and health habits being equal, those with the most social ties were least likely to catch a cold. If they did catch one, they produced less mucus. People whose daily life included frequent hugs likewise experienced fewer cold symptoms and less symptom severity (Cohen et al., 2015). More sociability meant less susceptibility. The cold fact is that the effect of social ties is nothing to sneeze at!

Close relationships give us an opportunity for “open heart therapy,” a chance to confide painful feelings (Frattaroli, 2006). Talking about a stressful event can temporarily arouse us, but in the long run it calms us, by calming limbic system activity (Lieberman et al., 2007; Mendolia & Kleck, 1993). In one study, 33 Holocaust survivors spent two hours recalling their experiences, many in intimate detail never before disclosed (Pennebaker et al., 1989). In the weeks following, most watched a video of their recollections and showed it to family and friends. Those who were most self-

“Woe to one who is alone and falls and does not have another to help.”

Ecclesiastes 4:10

Suppressing emotions can be detrimental to physical health. When psychologist James Pennebaker (1985) surveyed more than 700 undergraduate women, some of them reported a traumatic childhood sexual experience. The sexually abused women—

Even writing about personal traumas in a diary can help (Burton & King, 2008; Hemenover, 2003; Lyubomirsky et al., 2006). In an analysis of 633 trauma victims, writing therapy was as effective as psychotherapy in reducing psychological trauma (van Emmerik et al., 2013). In another experiment, volunteers who wrote trauma diaries had fewer health problems during the ensuing four to six months (Pennebaker, 1990). As one participant explained, “Although I have not talked with anyone about what I wrote, I was finally able to deal with it, work through the pain instead of trying to block it out. Now it doesn’t hurt to think about it.”

If we are aiming to exercise more, drink less, quit smoking, or attain a healthy weight, our social ties can tug us away from or toward our goal. If you are trying to achieve some goal, think about whether your social network can help or hinder you. That social net covers not only the people you know but friends of your friends, and friends of their friends. That’s three degrees of separation between you and the most remote people. Within that network, others can influence your thoughts, feelings, and actions without your awareness (Christakis & Fowler, 2009).

Reducing Stress

Having a sense of control, developing more optimistic thinking, and building social support can help us experience less stress and thus improve our health. Moreover, these factors interrelate: People who are upbeat about themselves and their future have tended also to enjoy health-

Aerobic Exercise

11-

aerobic exercise sustained exercise that increases heart and lung fitness; may also alleviate depression and anxiety.

Aerobic exercise is sustained, oxygen-

Exercise helps fight heart disease by strengthening the heart, increasing bloodflow, keeping blood vessels open, and lowering both blood pressure and the blood pressure reaction to stress (Ford, 2002; Manson, 2002). Inactivity can be toxic. People who exercise suffer half as many heart attacks as do others who are inactive (Powell et al., 1987; Visich & Fletcher, 2009). Exercise makes your muscles hungry for the fats that, if not used by muscles, can contribute to clogged arteries (Barinaga, 1997). In one study of over 650,000 American adults, walking 150 minutes per week predicted living seven more years (Moore et al., 2012). Regular exercise in later life also predicts better cognitive functioning and reduced risk of neurocognitive disorder and Alzheimer’s disease (Kramer & Erickson, 2007).

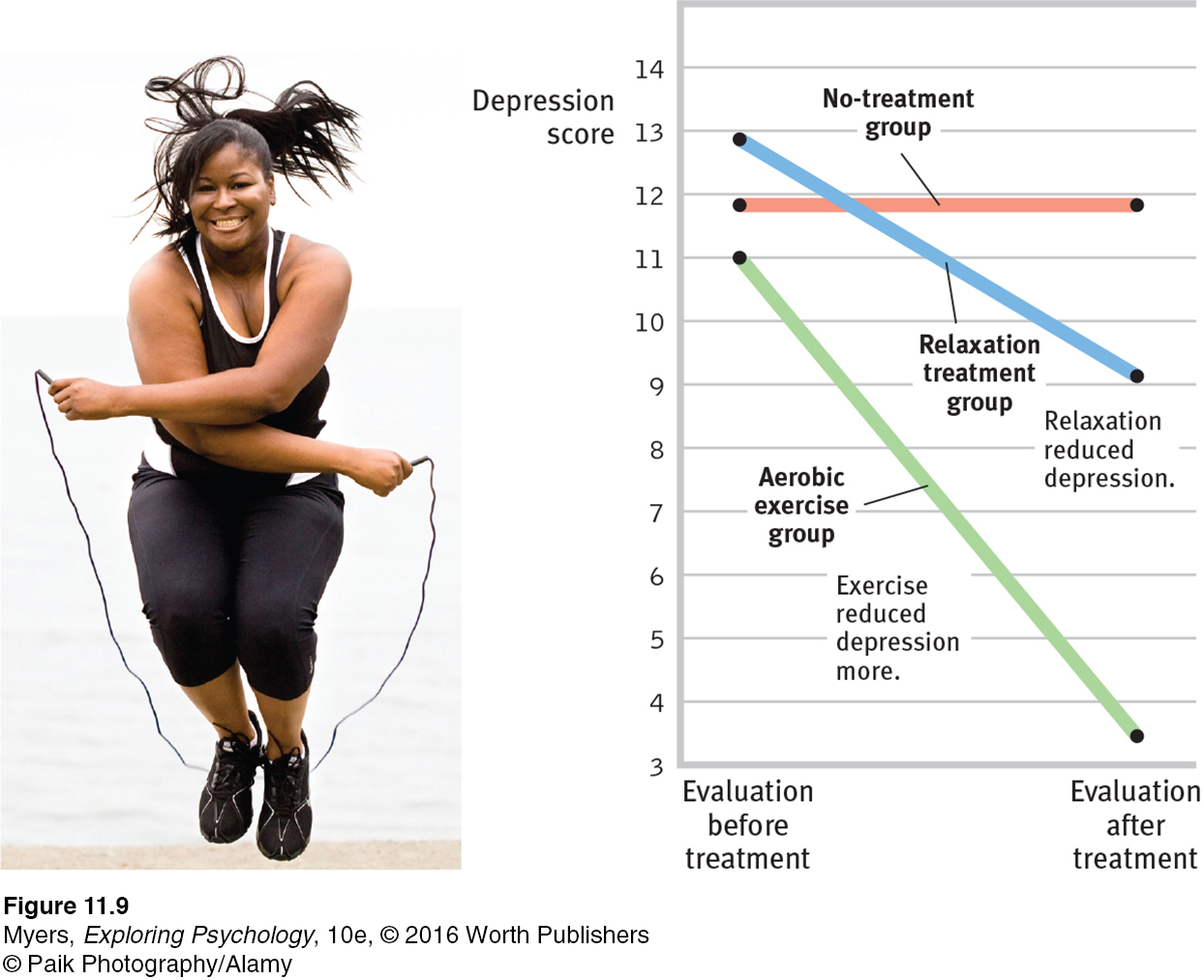

Does exercise also boost the spirit? Many studies reveal that aerobic exercise can reduce stress, depression, and anxiety. Americans, Canadians, and Britons who have at least three weekly aerobic exercise sessions manage stress better, exhibit more self-

But we could state this observation another way: Stressed and depressed people exercise less. These findings are correlations, and cause and effect are unclear. To sort out cause and effect, researchers experiment. They randomly assign stressed, depressed, or anxious people either to an aerobic exercise group or to a control group. Next, they measure whether aerobic exercise (compared with a control activity that doesn’t involve exercise) produces a change in stress, depression, anxiety, or some other health-

See LaunchPad’s Video: Random Assignment below for a helpful tutorial animation about this important part of effective research design.

See LaunchPad’s Video: Random Assignment below for a helpful tutorial animation about this important part of effective research design.

Dozens of other experiments and longitudinal studies confirm that exercise prevents or reduces depression and anxiety (Conn, 2010; Pinto Pereira et al., 2014; Windle et al., 2010). When experimenters randomly assigned depressed people to an exercise group, an antidepressant group, or a placebo pill group, exercise diminished depression as effectively as antidepressants—

Vigorous exercise provides a substantial and immediate mood boost (Watson, 2000). Even a 10-

On a simpler level, the sense of accomplishment and improved physique and body image that often accompany a successful exercise routine may enhance one’s self-

Relaxation and Meditation

11-

Knowing the damaging effects of stress, could we learn to counteract our stress responses by altering our thinking and lifestyle? In the late 1960s, some respected psychologists began experimenting with biofeedback, a system of recording, amplifying, and feeding back information about subtle physiological responses, many controlled by the autonomic nervous system. Biofeedback instruments mirror the results of a person’s own efforts, enabling the person to learn which techniques do (or do not) control a particular physiological response. After a decade of study, however, the initial claims for biofeedback seemed overblown and oversold (Miller, 1985). In 1995, a National Institutes of Health panel declared that biofeedback works best on tension headaches.

Simple methods of relaxation, which require no expensive equipment, produce many of the results biofeedback once promised. FIGURE 11.9 pointed out that aerobic exercise reduces depression. But did you notice in that figure that depression also decreased among women in the relaxation treatment group? More than 60 studies have found that relaxation procedures can also help alleviate headaches, hypertension, anxiety, and insomnia (Nestoriuc et al., 2008; Stetter & Kupper, 2002).

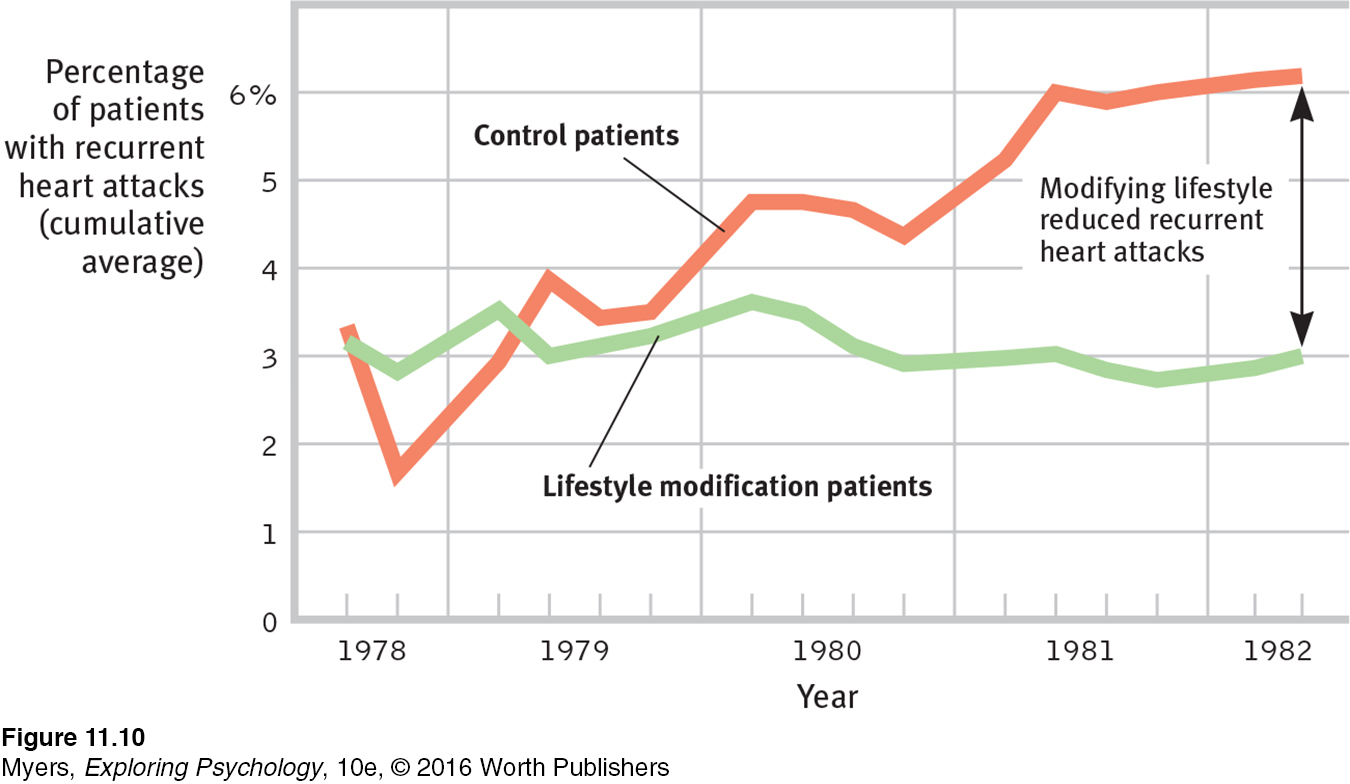

Such findings would not surprise Meyer Friedman, Ray Rosenman, and their colleagues. They tested relaxation in a program designed to help Type A heart attack survivors (who are more prone to heart attacks than their Type B peers) reduce their risk of future attacks. They randomly assigned hundreds of middle-

Time may heal all wounds, but relaxation can help speed that process. In one study, surgery patients were randomly assigned to two groups. Both groups received standard treatment, but the second group also experienced a 45-

“Sit down alone and in silence. Lower your head, shut your eyes, breathe out gently, and imagine yourself looking into your own heart. . . . As you breathe out, say ‘Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me.’ . . . Try to put all other thoughts aside. Be calm, be patient, and repeat the process very frequently.”

Gregory of Sinai, died 1346

mindfulness meditation a reflective practice in which people attend to current experiences in a nonjudgmental and accepting manner.

Meditation is a modern practice with a long history. In many of the world’s great religions, meditation has been used to reduce suffering and improve awareness, insight, and compassion. Numerous studies have confirmed the psychological benefits of meditation (Goyal et al., 2014; Sedlmeier et al., 2012). Today, it has found a new home in stress management programs, such as mindfulness meditation. If you were taught this practice, you would relax and silently attend to your inner state, without judging it (Kabat-

Practicing mindfulness may improve many health measures. In one study of 1140 people, some received mindfulness-

So what’s going on in the brain as we practice mindfulness? Correlational and experimental studies offer three explanations. Mindfulness

strengthens connections among regions in our brain. The affected regions are those associated with focusing our attention, processing what we see and hear, and being reflective and aware (Berkovich-

Ohana et al., 2014; Ives- Deliperi et al., 2011; Kilpatrick et al., 2011). Page 429activates brain regions associated with more reflective awareness (Davidson et al., 2003; Way et al., 2010). When labeling emotions, “mindful people” show less activation in the amygdala, a brain region associated with fear, and more activation in the prefrontal cortex, which aids emotion regulation (Creswell et al., 2007).

calms brain activation in emotional situations. This lower activation was clear in one study in which participants watched two movies—

one sad, one neutral. Those in the control group, who were not trained in mindfulness, showed strong differences in brain activation when watching the two movies. Those who had received mindfulness training showed little change in brain response to the two movies (Farb et al., 2010). Emotionally unpleasant images also trigger weaker electrical brain responses in mindful people than in their less mindful counterparts (Brown et al., 2013). A mindful brain is strong, reflective, and calm.

And then there are the mystics who seek to use the mind’s power to enable novocaine-

Exercise and meditation are not the only routes to healthy relaxation. Massage helps relax premature infants and those suffering pain. An analysis of 17 experiments revealed another benefit: Massage therapy relaxes muscles and helps reduce depression (Hou et al., 2010).

Faith Communities and Health

11-

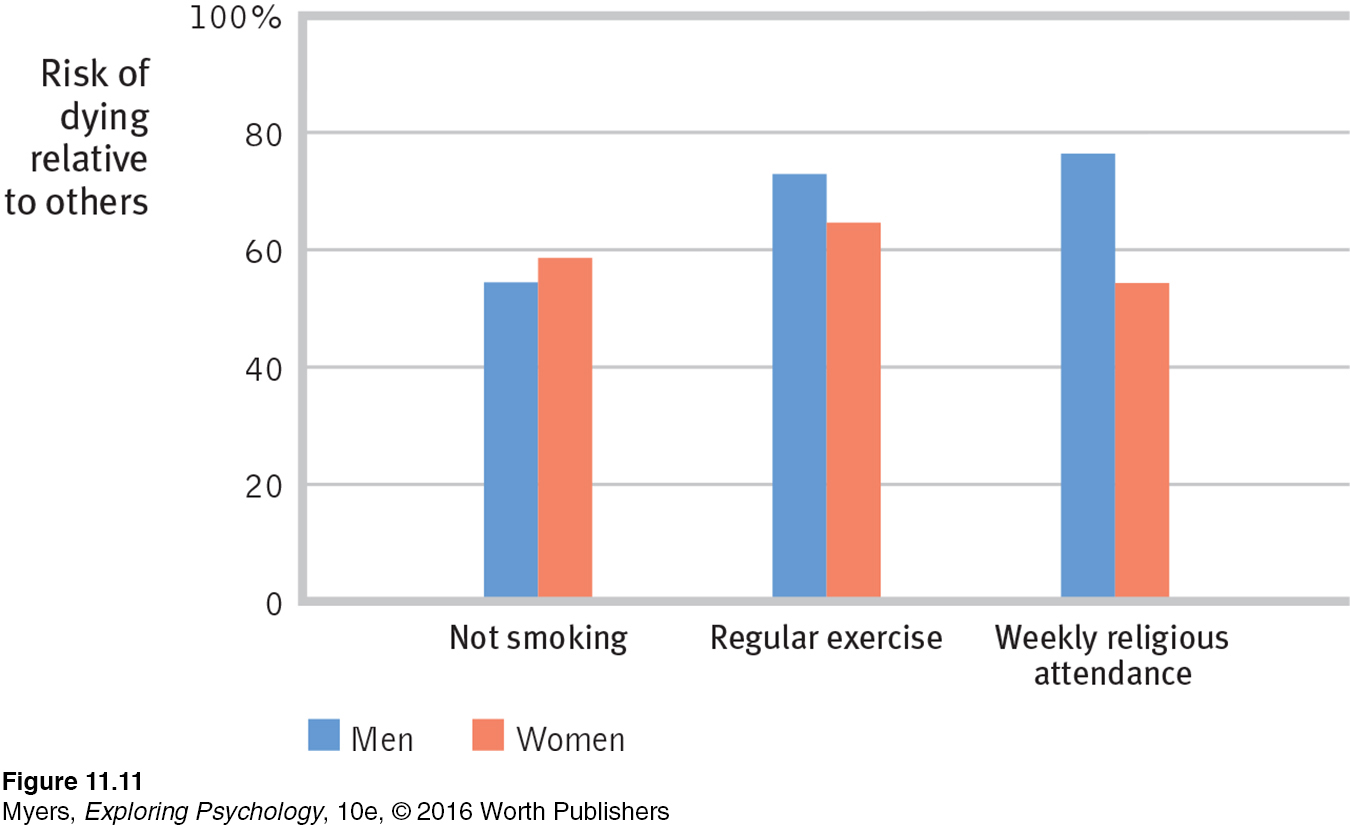

A wealth of studies—

How should we interpret such findings? Correlations are not cause-

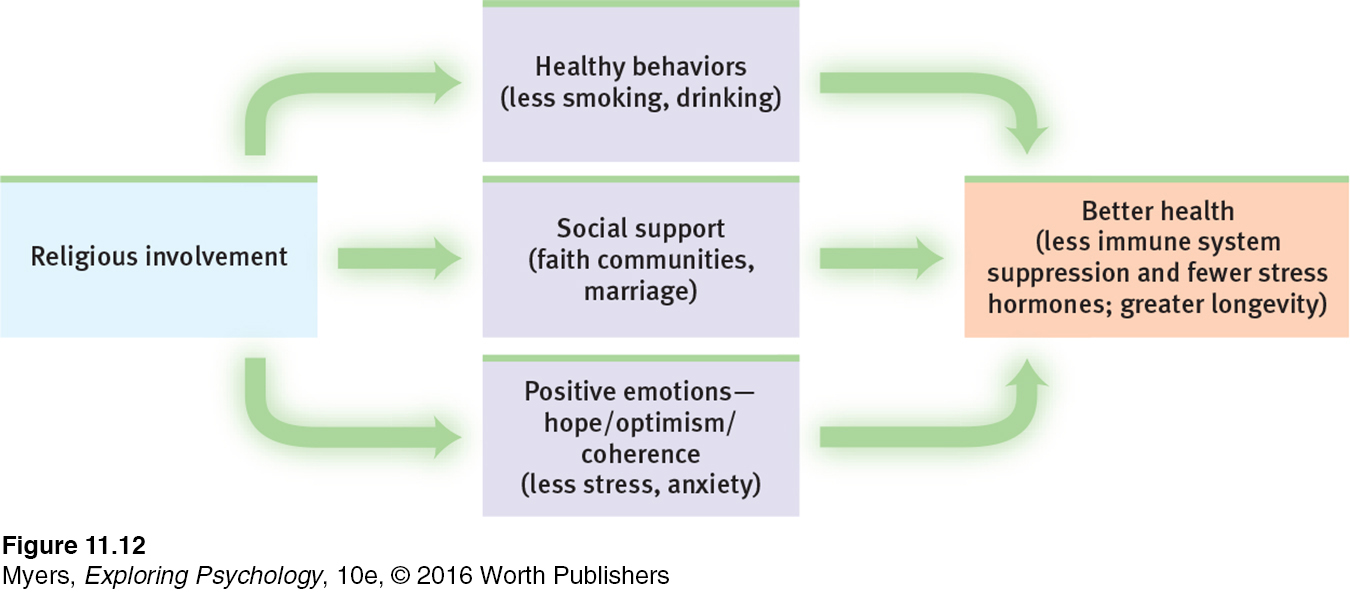

These correlational findings do not indicate that people who have not been religiously active can suddenly add 8 years of life if they start attending services and change nothing else. Nevertheless, the findings do indicate that religious involvement, like nonsmoking and exercise, is a predictor of health and longevity. Research points to three possible explanations for the religiosity-

Healthy behaviors Religion promotes self-

control (DeWall et al., 2014; McCullough & Willoughby, 2009). And that helps explain why religiously active people tend to smoke and drink much less and to have healthier lifestyles (Islam & Johnson, 2003; Koenig & Vaillant, 2009; Masters & Hooker, 2013; Park, 2007). In one Gallup survey of 550,000 Americans, 15 percent of the very religious were smokers, as were 28 percent of those nonreligious (Newport et al., 2010). But such lifestyle differences are not great enough to explain the dramatically reduced mortality in the Israeli religious settlements. In American studies, too, about 75 percent of the longevity difference remained when researchers controlled for unhealthy behaviors, such as inactivity and smoking (Musick et al., 1999). Social support Could social support explain the faith factor (Ai et al., 2007; George et al., 2002; Kim-

Yeary et al., 2012)? Faith is often a communal experience. To belong to one of these faith communities is to have access to a support network. Religiously active people are there for one another when misfortune strikes. Moreover, religion encourages marriage, another predictor of health and longevity. In the Israeli religious settlements, for example, divorce has been almost nonexistent. Page 431Positive emotions Even after controlling for gender, unhealthy behaviors, preexisting health problems, and social support, the mortality studies have found that religiously engaged people tend to live longer (Chida et al., 2009). Researchers speculate that religiously active people may benefit from a stable, coherent worldview, a sense of hope for the long-

term future, feelings of ultimate acceptance, and the relaxed meditation of prayer or other religious observances. These intervening variables may also help to explain why the religiously active seem to have healthier immune functioning, fewer hospital admissions, and, for AIDS patients, fewer stress hormones and longer survival (Ironson et al., 2002; Koenig & Larson, 1998; Lutgendorf et al., 2004).

RETRIEVE IT

Question

What are some of the tactics we can use to manage successfully the stress we cannot avoid?

Happiness

11-

People aspire to, and wish one another, health and happiness. And for good reason. Our state of happiness or unhappiness colors everything. Happy people perceive the world as safer and feel more confident. They are more decisive and cooperate more easily. They rate job applicants more favorably, savor their positive past experiences without dwelling on the negative, and are more socially connected. They live healthier and more energized and satisfied lives (Boehm et al., 2015; De Neve et al., 2013; Mauss et al., 2011; Stellar et al., 2015).

Moods matter. When your mood is gloomy, life as a whole seems depressing and meaningless—

feel-

Moreover—

The reverse is also true: Doing good also promotes good feeling. One survey of more than 200,000 people in 136 countries found that, nearly everywhere, people report feeling happier after spending money on others rather than on themselves (Aknin et al., 2013; Dunn et al., 2014). Feeling good even increases people’s willingness to donate kidneys. And kidney donation leaves donors feeling good (Brethel-

Positive Psychology

positive psychology the scientific study of human flourishing, with the goals of discovering and promoting strengths and virtues that help individuals and communities to thrive.

subjective well-being self-

William James was writing about the importance of happiness (“the secret motive for all [we] do”) as early as 1902. By the 1960s, the humanistic psychologists were interested in advancing human fulfillment. In the twenty-

Taken together, satisfaction with the past, happiness with the present, and optimism about the future define the positive psychology movement’s first pillar: positive well-

Positive psychology is about building not just a pleasant life, says Seligman, but also a good life that engages one’s skills, and a meaningful life that points beyond oneself. Thus, the second pillar, positive character, focuses on exploring and enhancing creativity, courage, compassion, integrity, self-

To test your own well-

To test your own well-

The third pillar, positive groups, communities, and cultures, seeks to foster a positive social ecology. This includes healthy families, communal neighborhoods, effective schools, socially responsible media, and civil dialogue.

“Positive psychology,” Seligman and colleagues have said (2005), “is an umbrella term for the study of positive emotions, positive character traits, and enabling institutions.” Its focus differs from psychology’s traditional interests during its first century, when attention was directed toward understanding and alleviating negative states—

In ages past, times of relative peace and prosperity have enabled cultures to turn their attention from repairing weakness and damage to promoting what Seligman (2002) has called “the highest qualities of life.” Prosperous fifth-

What Affects Our Well-Being?

11-

See LaunchPad’s Video: Naturalistic Observation below for a helpful tutorial animation about this type of research design.

See LaunchPad’s Video: Naturalistic Observation below for a helpful tutorial animation about this type of research design.

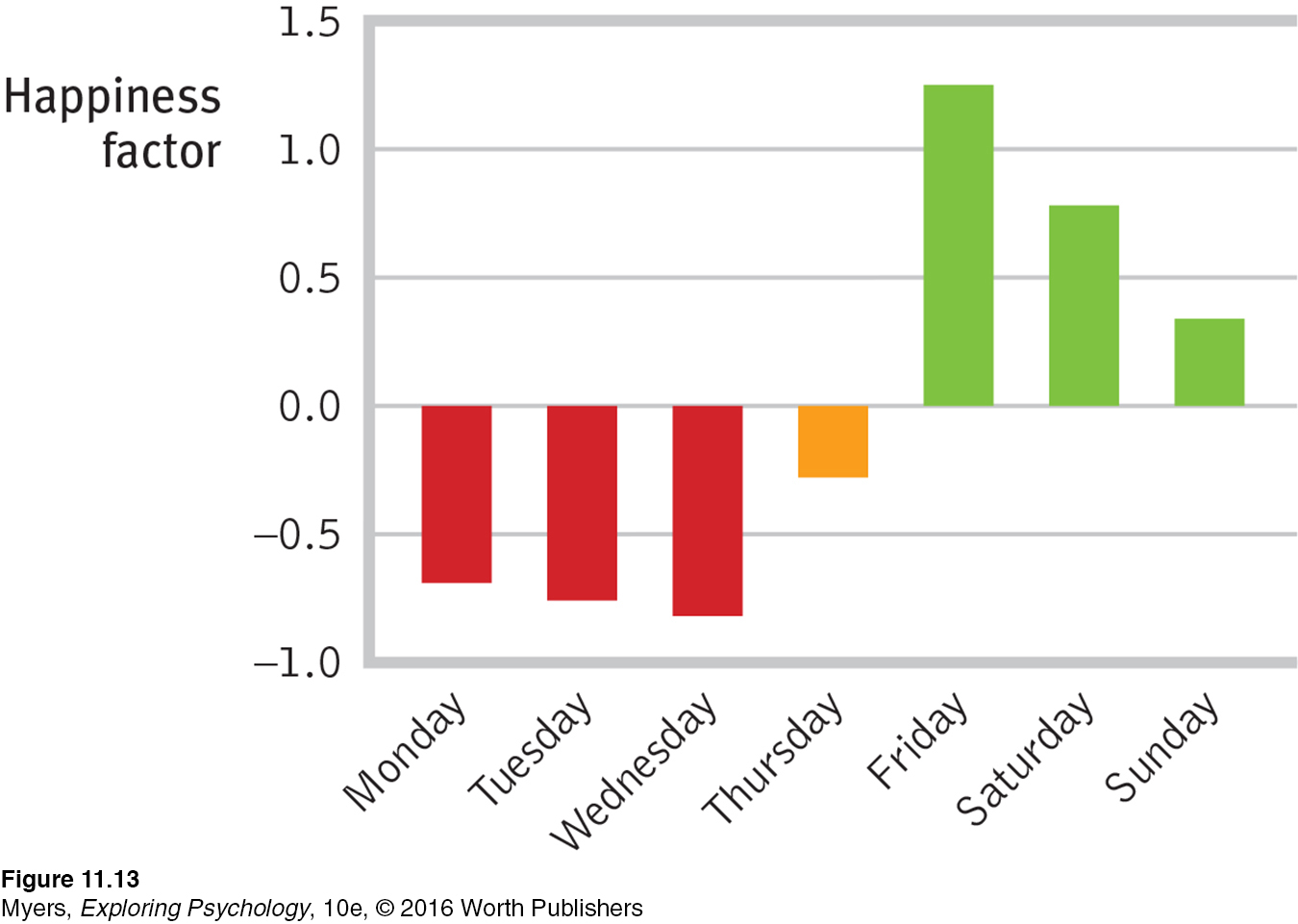

THE SHORT LIFE OF EMOTIONAL UPS AND DOWNS Are some days of the week happier than others? In what is likely psychology’s biggest-

“No happiness lasts for long.”

Seneca, Agamemnon, C.E. 60

Over the long run, our emotional ups and downs tend to balance out. This is true even over the course of the day. Positive emotion rises over the early to middle part of most days and then drops off (Kahneman et al., 2004; Watson, 2000). A stressful event—

Even when negative events drag us down for longer periods, our bad mood usually ends. A romantic breakup feels devastating, but eventually the wound heals. In one study, faculty members up for tenure expected their lives would be deflated by a negative decision. Actually, 5 to 10 years later, their happiness level was about the same as for those who received tenure (Gilbert et al., 1998).

Grief over the loss of a loved one or anxiety after a severe trauma (such as child abuse, rape, or the terrors of war) can linger. But usually, even tragedy is not permanently depressing. People who become blind or paralyzed may not completely recover their previous well-

The surprising reality: We overestimate the duration of our emotions and underestimate our resiliency.

“Weeping may tarry for the night, but joy comes with the morning.”

Psalm 30:5

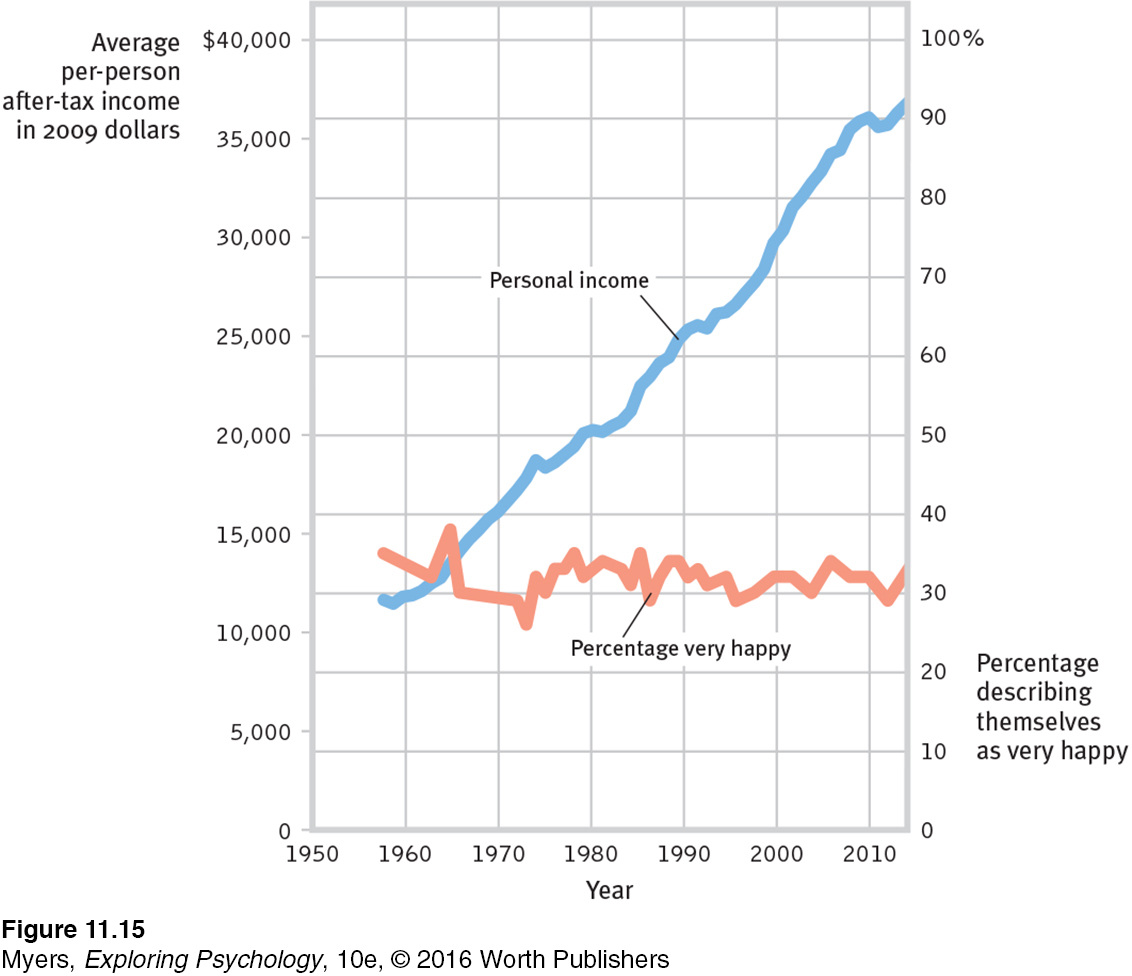

WEALTH AND WELL-

Money does buy happiness, up to a point. Having enough money to buy your way out of hunger and to have a sense of control over your life predicts greater happiness (Fischer & Boer, 2011). As Australian data confirm, the power of more money to increase happiness is strongest at low incomes (Cummins, 2006). A $1000 annual wage increase does a lot more for the average person in Malawi than for the average person in Switzerland. Raising low incomes will increase happiness more than will raising high incomes.

Once we have enough money for comfort and security, piling up more and more matters less and less. Experiencing luxury diminishes our savoring of life’s simpler pleasures (Cooney et al., 2014; Quoidbach et al., 2010). If you ski the Alps once, your neighborhood sledding hill pales. If you ski the Alps every winter, it becomes an ordinary part of life rather than an experience to treasure (Quoidbach et al., 2015).

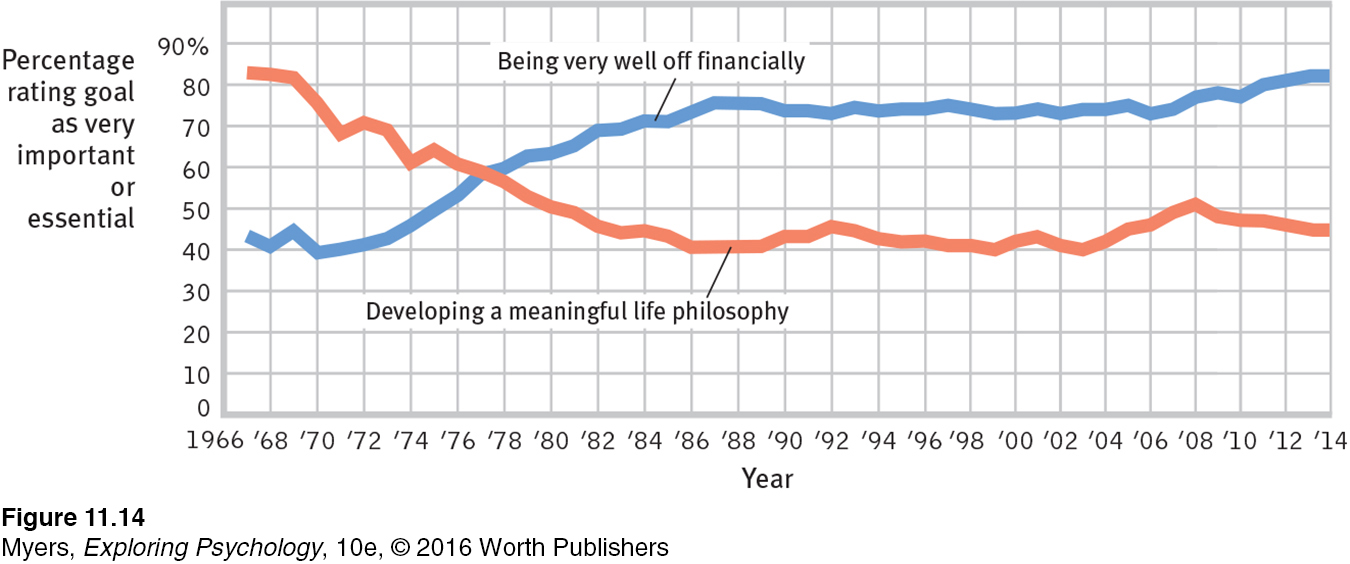

And consider this: During the last half-

HAPPINESS IS RELATIVE: ADAPTATION AND COMPARISON Two psychological principles explain why, for those who are not poor, more money buys little more than a temporary surge of happiness and why our emotions seem attached to elastic bands that pull us back from highs or lows. In its own way, each principle suggests that happiness is relative.

adaptation-level phenomenon our tendency to form judgments (of sounds, of lights, of income) relative to a neutral level defined by our prior experience.

HAPPINESS IS RELATIVE TO OUR OWN EXPERIENCE The adaptation-level phenomenon describes our tendency to judge various stimuli in comparison with our past experiences. As psychologist Harry Helson (1898-

“I have a ‘fortune cookie maxim’ that I’m very proud of: Nothing in life is quite as important as you think it is while you are thinking about it. So, nothing will ever make you as happy as you think it will.”

Nobel laureate psychologist Daniel Kahneman, Gallup interview, “What Were They Thinking?” 2005

So, could we ever create a permanent social paradise? Probably not (Campbell, 1975; Di Tella et al., 2010). People who have experienced a recent windfall—

relative deprivation the perception that one is worse off relative to those with whom one compares oneself.

HAPPINESS IS RELATIVE TO OTHERS’ SUCCESS We are always comparing ourselves with others. And whether we feel good or bad depends on who those others are (Lyubomirsky, 2001). We are slow-

When expectations soar above attainments, we feel disappointed. Thus, the middle-

For a 6.5-

For a 6.5-

The effect of comparison with others helps explain why students of a given level of academic ability tended to have a higher academic self-

Over the last half-

“Comparison is the thief of joy.”

Attributed to Theodore Roosevelt

Just as comparing ourselves with those who are better off creates envy, so counting our blessings as we compare ourselves with those worse off boosts our contentment. In one study, university women considered others’ deprivation and suffering (Dermer et al., 1979). They viewed vivid depictions of how grim city life could be in 1900. They imagined and then wrote about various personal tragedies, such as being burned and disfigured. Later, the women expressed greater satisfaction with their own lives. Similarly, when mildly depressed people have read about someone who was even more depressed, they felt somewhat better (Gibbons, 1986). “I cried because I had no shoes,” states a Persian saying, “until I met a man who had no feet.”

What Predicts Our Happiness Levels?

11-

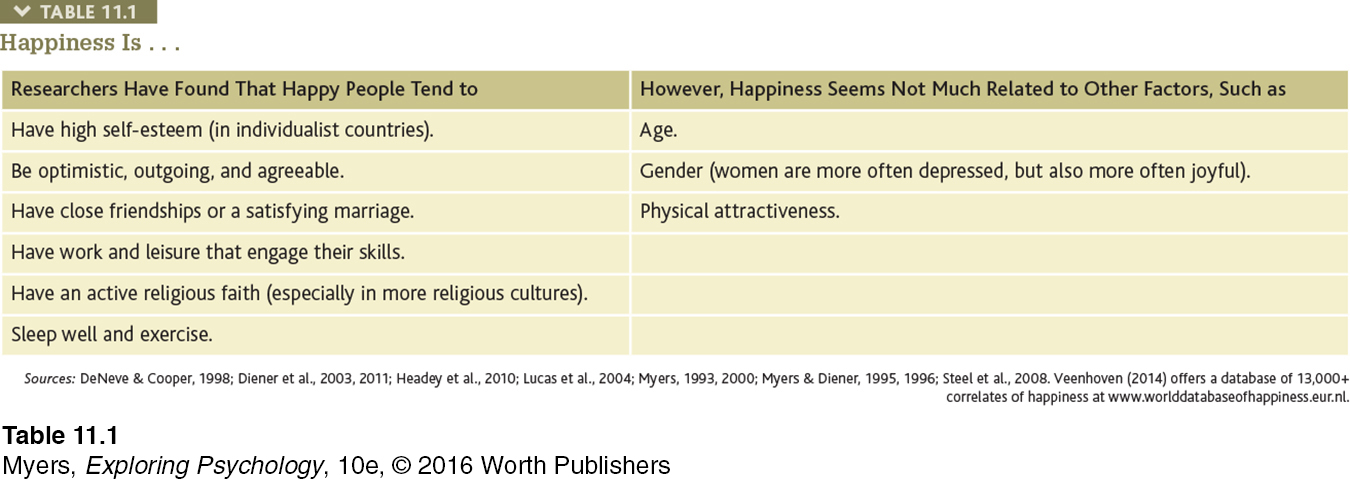

Happy people share many characteristics (TABLE 11.1 below). But why are some people normally so joyful and others so somber? Here, as in so many other areas, the answer is found in the interplay between nature and nurture.

Genes matter. In one study of hundreds of identical and fraternal twins, about 50 percent of the difference among people’s happiness ratings was heritable—

But our personal history and our culture matter, too. On the personal level, as we have seen, our emotions tend to balance around a level defined by our experience. On the cultural level, groups vary in the traits they value. Self-

Depending on our genes, our outlook, and our recent experiences, our happiness seems to fluctuate around our “happiness set point,” which disposes some people to be ever upbeat and others more negative. Even so, after following thousands of lives over two decades, researchers have determined that our satisfaction with life can change (Lucas & Donnellan, 2007). Happiness rises and falls, and it can be influenced by factors that are under our control. A striking example: In a long-

If we can enhance our happiness on an individual level, could we use happiness research to refocus our national priorities more on the pursuit of happiness? Many psychologists believe we could. Ed Diener (2006, 2009, 2013), supported by 52 colleagues, has proposed ways in which nations might measure national well-

Evidence-Based Suggestions for a Happier Life1

Your happiness, like your cholesterol level, is genetically influenced. Yet as cholesterol is also influenced by diet and exercise, so happiness is partly under your control (Layous & Lyubomirsky, 2014; Nes, 2010). Here are 11 research-

Realize that enduring happiness may not come from financial success. We adapt to change by adjusting our expectations. Neither wealth, nor any other circumstance we long for, will guarantee happiness.

Take control of your time. Happy people feel in control of their lives. To master your use of time, set goals and divide them into daily aims. We all tend to overestimate how much we will accomplish in any given day. The good news is that we generally underestimate how much we can accomplish in a year, given just a little daily progress.

Act happy. Research shows that people who are manipulated into a smiling expression feel better. So put on a happy face. Talk as if you feel positive self-

esteem, are optimistic, and are outgoing. We can often act our way into a happier state of mind. Seek work and leisure that engage your skills. Happy people often are in a zone called flow—absorbed in tasks that challenge but don’t overwhelm them. Passive forms of leisure (watching TV) often provide less flow experience than active forms, such as exercising, socializing, or expressing your musical interests.

Buy shared experiences rather than things. Compared with money spent on stuff, money buys more happiness when spent on experiences that you look forward to, enjoy, remember, and talk about (Carter & Gilovich, 2010; Kumar & Gilovich, 2013). This is especially so for socially shared experiences (Caprariello & Reis, 2012). The shared experience of a college education may cost a lot, but, as pundit Art Buchwald said, “The best things in life aren’t things.”

Join the “movement” movement. Aerobic exercise can relieve mild depression and anxiety as it promotes health and energy. Sound minds reside in sound bodies.

Give your body the sleep it wants. Happy people live active lives yet reserve time for renewing sleep and solitude. Many people suffer from sleep debt, with resulting fatigue, diminished alertness, and gloomy moods.

Give priority to close relationships. Intimate friendships can help you weather difficult times. Confiding is good for soul and body. Compared with unhappy people, happy people engage in less superficial small talk and more meaningful conversations (Mehl et al., 2010). So resolve to nurture your closest relationships by not taking your loved ones for granted. This means displaying to them the sort of kindness you display to others, affirming them, playing together, and sharing together.

Focus beyond self. Reach out to those in need. Perform acts of kindness. Happiness increases helpfulness (those who feel good do good). But doing good also makes us feel good.

Page 438Count your blessings and record your gratitude. Keeping a gratitude journal heightens well-

being (Emmons, 2007; Seligman et al., 2005). When something good happens, take time to appreciate and savor the experience (Sheldon & Lyubomirsky, 2012). Record positive events and why they occurred. Express your gratitude to others. Nurture your spiritual self. For many people, faith provides a support community, a reason to focus beyond self, and a sense of purpose and hope. That helps explain why people active in faith communities report greater-

than- average happiness and often cope well with crises.

RETRIEVE IT

Question

Which of the following factors do NOT predict self-

a. Age

b. Personality traits

c. Close relationships

d. Gender

e. Sleep and exercise

f. Active religious faith

REVIEW Health and Happiness

Learning Objectives

Test Yourself by taking a moment to answer each of these Learning Objective Questions (repeated here from within the chapter). Research suggests that trying to answer these questions on your own will improve your long-

Question

11-

Question

11-

Question

11-

Question

11-

Question

11-

Question

11-

Question

11-

Question

11-

Question

11-

Question

11-

Question

11-

Terms and Concepts to Remember

Test yourself on these terms.

Question

coping (p. 419) problem-focused coping (p. 419) emotion-focused coping (p. 419) learned helplessness (p. 419) external locus of control (p. 421) internal locus of control (p. 421) self-control (p. 421) aerobic exercise (p. 426) mindfulness meditation (p. 428) feel-good, do-good phenomenon (p. 431) positive psychology (p. 432) subjective well-being (p. 432) adaptation-level phenomenon (p. 434) relative deprivation (p. 435) | the perception that we control our own fate. our tendency to form judgments (of sounds, of lights, of income) relative to a neutral level defined by our prior experience. the ability to control impulses and delay short-term gratification for greater long-term rewards. the scientific study of human flourishing, with the goals of discovering and promoting strengths and virtues that help individuals and communities to thrive. sustained exercise that increases heart and lung fitness; may also alleviate depression and anxiety. self-perceived happiness or satisfaction with life. Used along with measures of objective well-being (for example, physical and economic indicators) to evaluate people's quality of life. attempting to alleviate stress directly— a reflective practice in which people attend to current experiences in a nonjudgmental and accepting manner. attempting to alleviate stress by avoiding or ignoring a stressor and attending to emotional needs related to our stress reaction. the perception that one is worse off relative to those with whom one compares oneself. people's tendency to be helpful when already in a good mood. alleviating stress using emotional, cognitive, or behavioral methods. the hopelessness and passive resignation an animal or person learns when unable to avoid repeated aversive events. the perception that chance or outside forces beyond our personal control determine our fate. |

Experience the Testing Effect

Test yourself repeatedly throughout your studies. This will not only help you figure out what you know and don’t know; the testing itself will help you learn and remember the information more effectively thanks to the testing effect.

Question 11.8

1. When faced with a situation over which you feel you have no sense of control, it is most effective to use (emotion/problem)-focused coping.

Question 11.9

2. Seligman's research showed that a dog will respond with learned helplessness if it has received repeated shocks and has had

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 11.10

3. When elderly patients take an active part in managing their own care and surroundings, their morale and health tend to improve. Such findings indicate that people do better when they experience an (internal/external) locus of control.

Question 11.11

4. People who have close relationships are less likely to die prematurely than those who do not, supporting the idea that

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 11.12

5. Because it triggers the release of mood-boosting neurotransmitters such as norepinephrine, serotonin, and the endorphins, exercise raises energy levels and helps alleviate depression and anxiety.

Question 11.13

6. Research on the faith factor has found that

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 11.14

7. One of the most consistent findings of psychological research is that happy people are also

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 11.15

8. psychology is a scientific field of study focused on how humans thrive and flourish.

Question 11.16

9. After moving to a new apartment, you find the street noise irritatingly loud, but after a while, it no longer bothers you. This reaction illustrates the

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 11.17

10. A philosopher observed that we cannot escape envy, because there will always be someone more successful, more accomplished, or richer with whom to compare ourselves. In psychology, this observation is embodied in the principle.

Use  to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in

to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in  .

.