14.1 Basic Concepts of Psychological Disorders

14-

Most of us would agree that a family member who is depressed and isolated for three months has a psychological disorder. But what should we say about a grieving father who can’t resume his usual social activities three months after his child has died? Where do we draw the line between clinical depression and understandable grief? Between bizarre irrationality and zany creativity? Between abnormality and normality? In their search for answers, theorists and clinicians ask:

How should we define psychological disorders?

How should we understand disorders? How do underlying biological factors contribute to disorder? How do troubling environments influence our well-

being? And how do these effects of nature and nurture interact? How should we classify psychological disorders? And can we do so in a way that allows us to help people without stigmatizing or labeling them?

What do we know about rates of psychological disorders? How many people have them? Who is vulnerable, and when?

“Who in the rainbow can draw the line where the violet tint ends and the orange tint begins? Distinctly we see the difference of the colors, but where exactly does the one first blendingly enter into the other? So with sanity and insanity.”

Herman Melville, Billy Budd, Sailor, 1924

psychological disorder a syndrome marked by a clinically significant disturbance in an individual’s cognition, emotion regulation, or behavior.

A psychological disorder is a syndrome (a symptom collection) marked by a “clinically significant disturbance in an individual’s cognition, emotion regulation, or behavior” (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Such thoughts, emotions, or behaviors are dysfunctional or maladaptive—

Distress often accompanies dysfunctional behaviors. Marc, Greta, and Stuart were all distressed by their behaviors or emotions.

Over time, definitions of what makes for a “significant disturbance” have varied. In 1973, the American Psychiatric Association dropped homosexuality as a disorder after mental health workers came to consider same-

RETRIEVE IT

Question

A lawyer is distressed by feeling the need to wash his hands 100 times a day. He has no time left to meet with clients, and his colleagues are wondering about his competence. His behavior would probably be labeled disordered, because it is

—that is, it interferes with his day-

Understanding Psychological Disorders

14-

The way we view a problem influences how we try to solve it. In earlier times, people often thought that strange behaviors were evidence that strange forces—

Reformers, such as Philippe Pinel (1745–

Barbaric treatments for mental illness linger even today. In some places, people are chained to a bed, confined to their rooms, or even locked in a space with wild hyenas, in the belief that the animals will see and attack evil spirits (Hooper, 2013). Noting the physical and emotional damage of such restraint, the World Health Organization launched a “chain-

The Medical Model

medical model the concept that diseases, in this case psychological disorders, have physical causes that can be diagnosed, treated, and, in most cases, cured, often through treatment in a hospital.

By the 1800s, a medical breakthrough prompted further reform. Researchers discovered that syphilis, a sexually transmitted infection, invades the brain and distorts the mind. This discovery triggered an excited search for physical causes of mental disorders and for treatments that would cure them. Hospitals replaced asylums, and the medical model of mental disorders was born. This model is reflected in words we still use today. We speak of the mental health movement. A mental illness (also called a psychopathology) needs to be diagnosed on the basis of its symptoms. It needs to be treated through therapy, which may include treatment in a psychiatric hospital. Recent discoveries that genetically influenced abnormalities in brain structure and biochemistry contribute to many disorders have energized the medical perspective.

The Biopsychosocial Approach

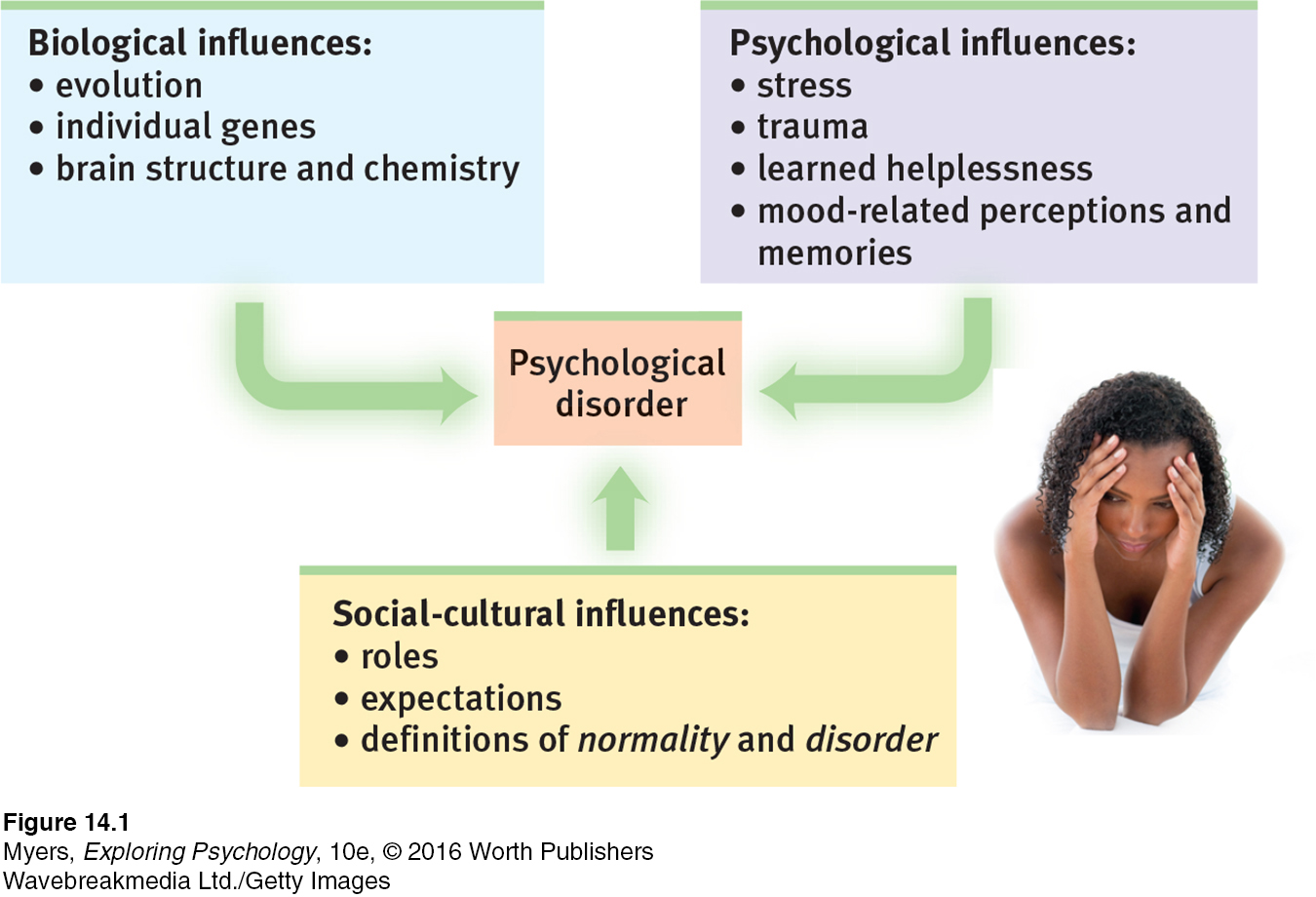

To call psychological disorders “sicknesses” tilts research heavily toward the influence of biology and away from the influence of our personal histories and social and cultural surroundings. But as we have seen throughout this text, biological, psychological, and social-

The environment’s influence on disorders can be seen in culture-

Two other disorders—

epigenetics the study of environmental influences on gene expression that occur without a DNA change.

Disorders reflect genetic predispositions and physiological states, psychological dynamics, and social and cultural circumstances. The biopsychosocial approach emphasizes that mind and body are inseparable (see FIGURE 14.1). Negative emotions contribute to physical illness, and physical abnormalities contribute to negative emotions. As research on epigenetics shows, our environment can also affect whether a gene is expressed, thus affecting the development of psychological disorders.

RETRIEVE IT

Question

Are psychological disorders universal, or are they culture-

Question

What is the biopsychosocial approach, and why is it important in our understanding of psychological disorders?

Classifying Disorders—and Labeling People

14-

In biology, classification creates order. To classify an animal as a “mammal” says a great deal—

But diagnostic classification gives more than a thumbnail sketch of a person’s disordered behavior, thoughts, or feelings. In psychiatry and psychology, classification also attempts to

predict a disorder’s future course.

suggest appropriate treatment.

prompt research into a disorder’s causes.

DSM-5 the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition; a widely used system for classifying psychological disorders.

The most common tool for describing disorders and estimating how often they occur is the American Psychiatric Association’s 2013 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, now in its fifth edition (DSM-5). Physicians and mental health workers use the DSM-

Insomnia Disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In the new DSM-

Real-

Critics have long faulted the DSM for casting too wide a net, and for bringing “almost any kind of behavior within the compass of psychiatry” (Eysenck et al., 1983). Some now worry that the DSM-

THINKING CRITICALLY ABOUT

ADHD—

14-

Eight-

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) a psychological disorder marked by extreme inattention and/or hyperactivity and impulsivity.

If taken for a psychological evaluation, Todd may be diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Some 11 percent of American 4-

To skeptics, being distractible, fidgety, and impulsive sounds like a “disorder” caused by a single genetic variation: a Y chromosome (the male sex chromosome). And sure enough, ADHD is diagnosed three times more often in boys than in girls. Does energetic child + boring school = ADHD overdiagnosis? Is the label being applied to healthy schoolchildren who, in more natural outdoor environments, would seem perfectly normal? Is ADHD a disease that is marketed by companies offering drugs that treat it (Thomas, 2015)?

Skeptics think so. In the decade after 1987, they note, the proportion of American children being treated for ADHD nearly quadrupled (Olfson et al., 2003). Minority youth less often receive an ADHD diagnosis than do White youth, but this difference has shrunk as minority ADHD diagnoses have increased (Genahun at al., 2013). How commonplace the diagnosis is depends in part on teacher referrals. Some teachers refer lots of kids for ADHD assessment, others none. ADHD rates have varied by a factor of 10 in different counties of New York State (Carlson, 2000). Depending on where they live, children who are “a persistent pain in the neck in school” are often diagnosed with ADHD and given powerful prescription drugs, notes Peter Gray (2010). But the problem may reside less in the child than in today’s abnormal environment, which forces children to do what evolution has not prepared them to do—

Not everyone agrees that ADHD is being overdiagnosed. Some argue that today’s more frequent diagnoses of ADHD reflect increased awareness of the disorder, especially in those areas where rates are highest. They acknowledge that diagnoses can be inconsistent—

What, then, is known about ADHD’s causes? It is not caused by too much sugar or poor schools. ADHD often coexists with a learning disorder or with defiant and temper-

The bottom line: Extreme inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity can derail social, academic, and vocational achievements, and these symptoms can be treated with medication and other therapies (Hinshaw & Scheffler, 2014). But the debate continues over whether normal high energy is too often diagnosed as a psychiatric disorder, and whether there is a cost to the long-

Other critics register a more basic complaint—

The biasing power of labels was clear in a classic study. David Rosenhan (1973) and seven others went to hospital admissions offices, complaining (falsely) of “hearing voices” saying empty, hollow, and thud. Apart from this complaint and giving false names and occupations, they answered questions truthfully. All eight healthy people were misdiagnosed with disorders.

Should we be surprised? Surely not. As one psychiatrist noted, if someone swallowed blood, went to an emergency room, and spat it up, would we blame a doctor for diagnosing a bleeding ulcer? But what followed the Rosenhan study diagnoses was startling. Until being released an average of 19 days later, these eight “patients” showed no other symptoms. Yet after analyzing their (quite normal) life histories, clinicians were able to “discover” the causes of their disorders, such as having mixed emotions about a parent. Even the patients’ routine note-

In another study, people watched videotaped interviews. If told the interviewees were job applicants, the viewers perceived them as normal (Langer & Abelson, 1974, 1980). Other viewers who were told they were watching psychiatric or cancer patients perceived the same interviewees as “different from most people.” Therapists who thought they were watching an interview of a psychiatric patient perceived him as “frightened of his own aggressive impulses,” a “passive, dependent type,” and so forth. As Rosenhan discovered, a label can have “a life and an influence of its own.” Labels matter.

Labels also have power outside the laboratory. Getting a job or finding a place to rent can be a challenge for people recently released from a mental hospital. Label someone as “mentally ill” and people may fear them as potentially violent (see Thinking Critically About: Are People With Psychological Disorders Dangerous?). Such negative reactions may fade as people better understand that many psychological disorders involve diseases of the brain, not failures of character (Solomon, 1996). Public figures have helped foster this understanding by speaking openly about their own struggles with disorders such as depression and substance abuse. The more contact we have with people with disorders, the more accepting our attitudes become (Kolodziej & Johnson, 1996).

THINKING CRITICALLY ABOUT

Are People With Psychological Disorders Dangerous?

14-

September 16, 2013, started like any other Monday at Washington, DC’s, Navy Yard, with people arriving early to begin work. Then government contractor Aaron Alexis parked his car, entered the building, and began shooting people. An hour later, 13 people were dead, including Alexis. Reports later confirmed that Alexis had a history of mental illness. Before the shooting, he had stated that an “ultra low frequency attack is what I’ve been subject to for the last three months. And to be perfectly honest, that is what has driven me to this.” After a horrifying mass shooting in a Connecticut elementary school in 2012, New York’s governor declared, “People who have mental issues should not have guns” (Kaplan & Hakim, 2013). These devastating mass shootings, like many others since then, reinforced public perceptions that people with psychological disorders pose a threat (Barry et al., 2013; Jorm et al., 2012). So did an incident in March of 2015, when Germanwings co-

Does scientific evidence support the governor’s statement? If disorders actually increase the risk of violence, then denying people with psychological disorders the right to bear arms might reduce violent crimes. But real life tells a different story. Most people with mental disorders commit no violent crimes, and the vast majority of violent crimes are committed by people with no diagnosed disorder (Fazel & Grann, 2006; Skeem et al., 2015; Walkup & Rubin, 2013).

People with disorders are more likely to be victims than perpetrators of violence (Marley & Bulia, 2001). According to the U.S. Surgeon General’s Office (1999, p. 7), “There is very little risk of violence or harm to a stranger from casual contact with an individual who has a mental disorder.” The bottom line: Psychological disorders only rarely lead to violent acts, and focusing gun restrictions only on mentally ill people will likely not reduce gun violence (Friedman, 2012).

If mental illness is not a good predictor of violence, what is? Better predictors are a history of violence, use of alcohol or drugs, and access to a gun. The mass-

Mental disorders seldom lead to violence, and clinical prediction of violence is unreliable. What, then, are the triggers for the few people with psychological disorders who do commit violent acts? For some, the trigger is substance abuse. For others, like the Navy Yard shooter, it’s threatening delusions and hallucinated voices that command them to act (Douglas et al., 2009; Elbogen & Johnson, 2009; Fazel et al., 2009, 2010). Whether people with mental disorders who turn violent should be held responsible for their behavior remains controversial. U.S. President Ronald Reagan’s near-

Which decision was correct? The first two, which blamed Loughner’s “madness” for clouding his judgment? Or the final one, which decided that he should be held responsible for the acts he committed? As we come to better understand the biological and environmental bases for all human behavior, from generosity to vandalism, when should we—

“What’s the use of their having names,” the Gnat said, “if they won’t answer to them?”

“No use to them,” said Alice; “but it’s useful to the people that name them, I suppose.”

Lewis Carroll, Through the Looking-

Despite their risks, diagnostic labels have benefits. They help mental health professionals communicate about their cases and study the causes and treatments of disorder. Clients are often relieved to learn that the nature of their suffering has a name, and that they are not alone in experiencing their symptoms.

To test your ability to form diagnoses, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Classifying Disorders.

To test your ability to form diagnoses, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Classifying Disorders.

RETRIEVE IT

Question

What is the value, and what are the dangers, of labeling individuals with disorders?

Rates of Psychological Disorders

14-

Who is most vulnerable to psychological disorders? At what times of life? To answer such questions, various countries have conducted lengthy, structured interviews with representative samples of thousands of their citizens. After asking hundreds of questions that probe for symptoms—

How many people have, or have had, a psychological disorder? More than most of us suppose:

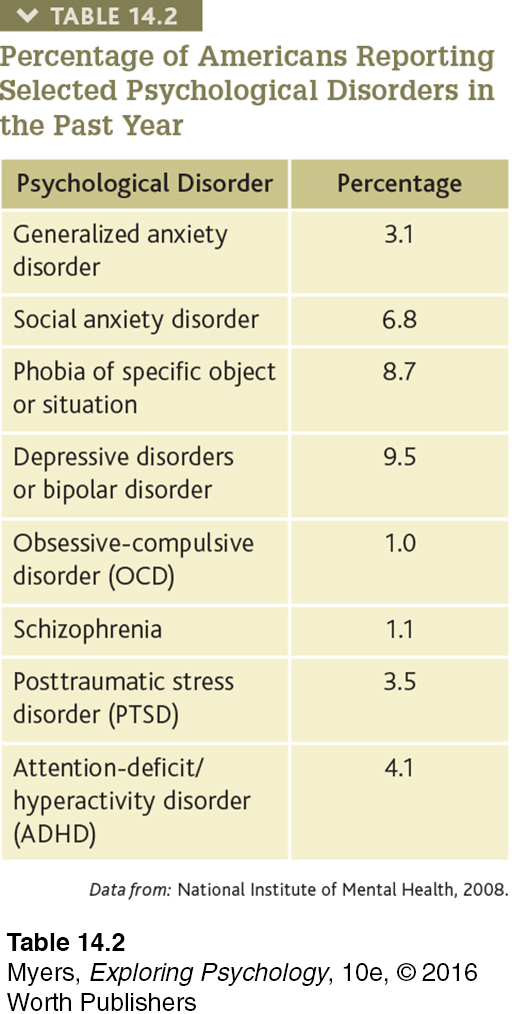

The U.S. National Institute of Mental Health (2008, based on Kessler et al., 2005) has estimated that just over 1 in 4 adult Americans “suffer from a diagnosable mental disorder in a given year” (TABLE 14.2).

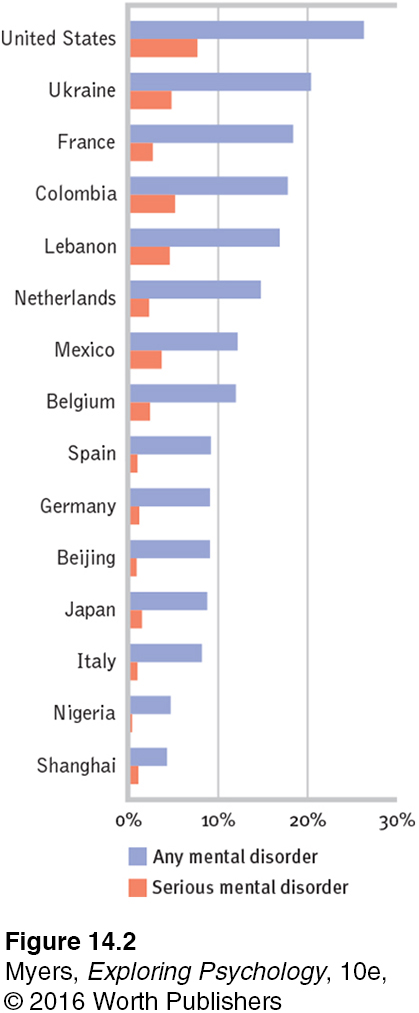

A World Health Organization (2004) study—

based on 90- minute interviews of 60,463 people— estimated the number of prior- year mental disorders in 20 countries. As FIGURE 14.2 illustrates, the lowest rate of reported mental disorders was in China (Shanghai), the highest rate in the United States. Moreover, people immigrating to the United States from Mexico, Africa, and Asia averaged better mental health than their U.S. counterparts with the same ethnic heritage (Breslau et al., 2007; Maldonado- Molina et al., 2011). For example, compared with people who have recently immigrated from Mexico, Mexican- Americans born in the United States are at greater risk of mental disorder— a phenomenon known as the immigrant paradox (Schwartz et al., 2010).

Data from: National Institute of Mental Health, 2008.

See LaunchPad’s Video: Correlational Studies below for a helpful tutorial animation about this research design.

See LaunchPad’s Video: Correlational Studies below for a helpful tutorial animation about this research design.

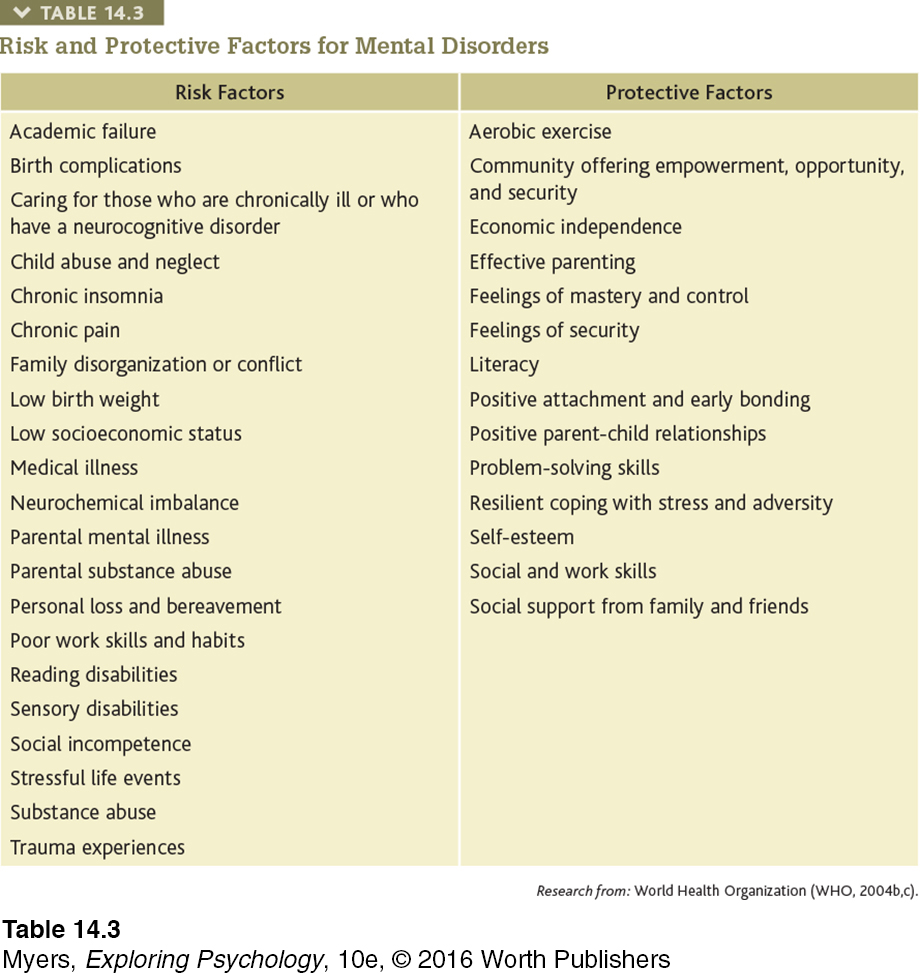

What increases vulnerability to mental disorders? As we have seen, the answer varies with the disorder (TABLE 14.3). One predictor of mental disorders—

At what times of life do disorders strike? Usually by early adulthood. “Over 75 percent of our sample with any disorder had experienced [their] first symptoms by age 24,” reported Lee Robins and Darrel Regier (1991, p. 331). Among the earliest to appear are the symptoms of antisocial personality disorder (median age 8) and of phobias (median age 10). Alcohol use disorder, obsessive-

RETRIEVE IT

Question

What is the relationship between poverty and psychological disorders?

REVIEW Basic Concepts of Psychological Disorders

Learning Objectives

Test Yourself by taking a moment to answer each of these Learning Objective Questions (repeated here from within the chapter). Research suggests that trying to answer these questions on your own will improve your long-

Question

14-

Question

14-

Question

14-

Question

14-

Question

14-

Question

14-

Terms and Concepts to Remember

Test yourself on these terms.

Question

psychological disorder (p. 528) medical model (p. 529) epigenetics (p. 530) DSM- attention- | a syndrome marked by a clinically significant disturbance in an individual's cognition, emotion regulation, or behavior. the concept that diseases, in this case psychological disorders, have physical causes that can be diagnosed, treated, and, in most cases, cured, often through treatment in a hospital. the study of environmental influences on gene expression that occur without a DNA change. a psychological disorder marked by extreme inattention and/or hyperactivity and impulsivity. the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition; a widely used system for classifying psychological disorders. |

Experience the Testing Effect

Test yourself repeatedly throughout your studies. This will not only help you figure out what you know and don’t know; the testing itself will help you learn and remember the information more effectively thanks to the testing effect.

Question 14.1

1. Two major disorders that are found worldwide are schizophrenia and .

Question 14.2

2. Anna is embarrassed that it takes her several minutes to parallel park her car. She usually gets out of the car once or twice to inspect her distance both from the curb and from the nearby cars. Should she worry about having a psychological disorder?

Question 14.3

3. What is susto, and is this a culture-specific or universal psychological disorder?

Question 14.4

4. A therapist says that psychological disorders are sicknesses and people with these disorders should be treated as patients in a hospital. This therapist believes in the model.

Question 14.5

5. Many psychologists reject the “disorders-as-illness” view and instead contend that other factors may also be involved—

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 14.6

6. Why is the DSM, and the DSM-

Question 14.7

7. One predictor of psychiatric disorders that crosses ethnic and gender lines is .

Question 14.8

8. The symptoms of ________ appear around age 10; ________ tend[s] to appear later, around age 25.

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Use  to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in

to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in  .

.