3.1 Consciousness: Some Basic Concepts

Every science has concepts so fundamental they are nearly impossible to define. Biologists agree on what is alive but not on precisely what life is. In physics, matter and energy elude simple definition. To psychologists, consciousness is similarly a fundamental yet slippery concept.

Defining Consciousness

3-

At its beginning, psychology was “the description and explanation of states of consciousness” (Ladd, 1887). But during the first half of the twentieth century, the difficulty of scientifically studying consciousness led many psychologists—

“Psychology must discard all reference to consciousness.”

Behaviorist John B. Watson (1913)

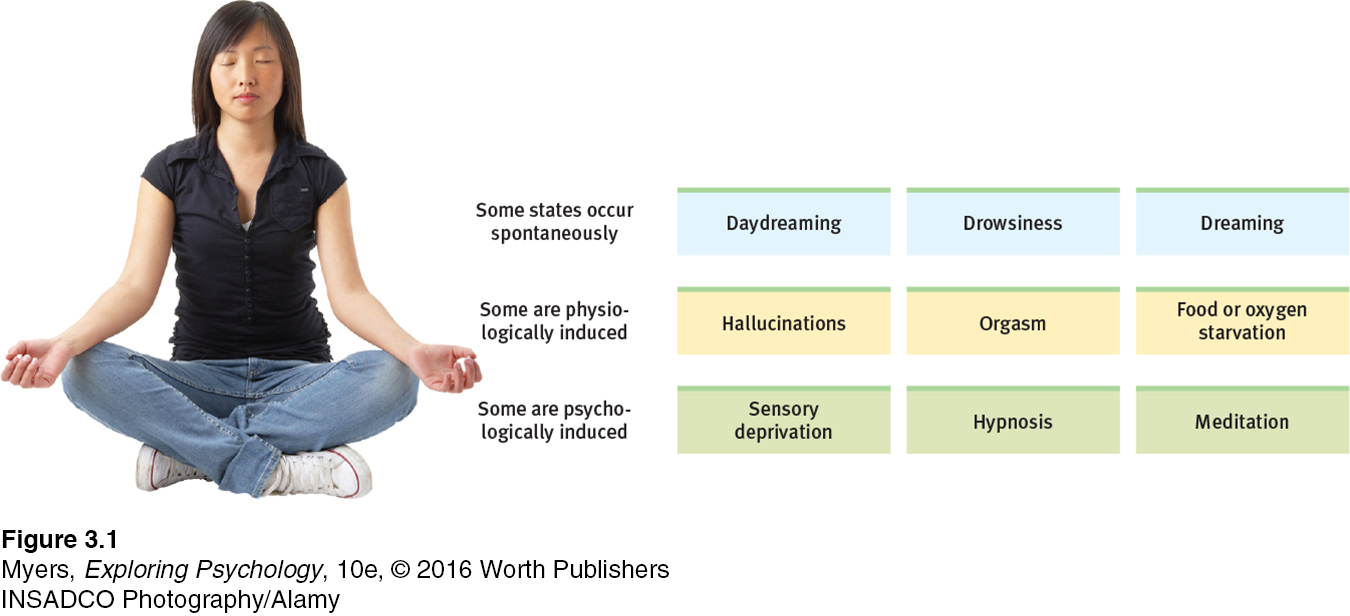

After 1960, psychology began regaining consciousness. Neuroscience advances linked brain activity to sleeping, dreaming, and other mental states. Researchers began studying consciousness altered by drugs, hypnosis, and meditation. (More on hypnosis in Chapter 6 and meditation in Chapter 11.) Psychologists of all persuasions were affirming the importance of cognition, or mental processes.

consciousness our awareness of ourselves and our environment.

Most psychologists now define consciousness as our awareness of ourselves and our environment (Paller & Suzuki, 2014). This awareness allows us to assemble information from many sources as we reflect on our past, adapt to our present, and plan for our future. And it focuses our attention when we learn a complex concept or behavior. When learning to drive, we focus on the car and the traffic. With practice, driving becomes semi-

Studying Consciousness

Today’s science explores the biology of consciousness. Scientists now assume, in the words of neuroscientist Marvin Minsky (1986, p. 287), that “the mind is what the brain does.”

cognitive neuroscience the interdisciplinary study of the brain activity linked with cognition (including perception, thinking, memory, and language).

Evolutionary psychologists presume that consciousness offers a reproductive advantage (Barash, 2006; Murdik et al., 2011). By considering consequences and reading others’ intentions, consciousness helps us to cope with novel situations and act in our long-

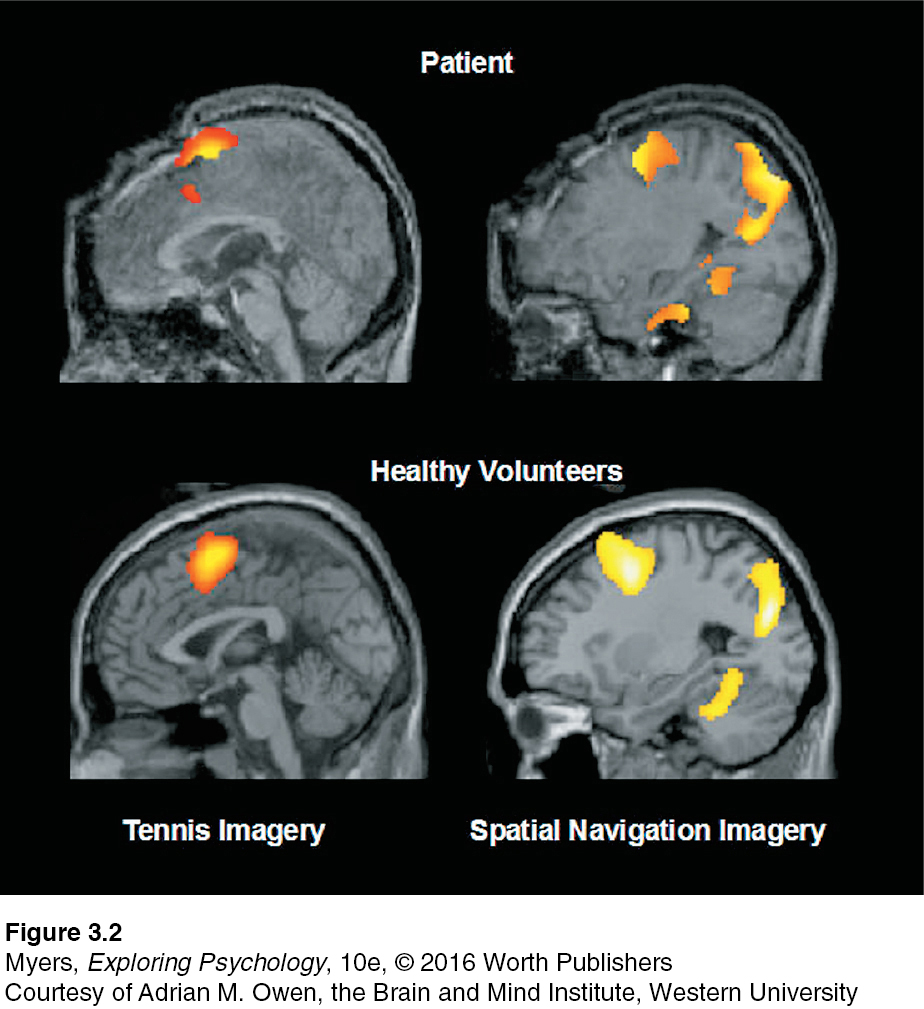

A stunning demonstration of consciousness appeared in brain scans of a noncommunicative patient—

Some neuroscientists believe that conscious experience arises from synchronized activity across the brain (Gaillard et al., 2009; Koch & Greenfield, 2007; Schurger et al., 2010). If a stimulus activates enough brain-

RETRIEVE IT

Question

Those working in the interdisciplinary field called study the brain activity associated with the mental processes of perception, thinking, memory, and language.

Selective Attention

3-

selective attention the focusing of conscious awareness on a particular stimulus.

Through selective attention, our awareness focuses, like a flashlight beam, on a minute aspect of all that we experience. We may think we can fully attend to a conversation or a class lecture while checking and returning text messages. Actually, our consciousness focuses on but one thing at a time.

By one estimate, our five senses take in 11,000,000 bits of information per second, of which we consciously process about 40 (Wilson, 2002). Yet our mind’s unconscious track intuitively makes great use of the other 10,999,960 bits. Until reading this sentence, for example, you have been unaware of the chair pressing against your bottom or that your nose is in your line of vision. Now, suddenly, your attentional spotlight shifts. You feel the chair, your nose stubbornly intrudes on the words before you. While focusing on these words, you’ve also been blocking other parts of your environment from awareness, though your peripheral vision would let you see them easily. You can change that. As you stare at the X below, notice what surrounds these sentences (the edges of the page, the desktop, the floor).

X

“Has a generation of texters, surfers, and twitterers evolved the enviable ability to process multiple streams of novel information in parallel? Most cognitive psychologists doubt it.”

Steven Pinker, “Not at All,” 2011

A classic example of selective attention is the cocktail party effect—

Selective Attention and Accidents

Talk, text, route plan, or attend to music selections while driving, and your selective attention will shift back and forth between the road and its electronic competition. Indeed, it shifts more often than we realize. One study left people in a room free to surf the Internet and to control and watch a TV. On average, participants guessed their attention switched 15 times during the 28-

Watch the thought-

Watch the thought-

When phone partners use a video phone that enables them to see the road and pause their conversation, accident rates in driving simulations are no greater than when drivers talk to an in-

We pay a toll for switching attentional gears, especially when we shift to complex tasks, like noticing and avoiding cars around us. The toll is a slight and sometimes fatal delay in coping (Rubenstein et al., 2001). About 28 percent of traffic accidents occur when people are chatting or texting on cell phones—

Even hands-

University of Sydney researchers analyzed phone records for the moments before a car crash. Cell-

phone users (even those with hands- free sets) were, like the average drunk driver, four times more at risk (McEvoy et al., 2005, 2007). Having a passenger increased risk only 1.6 times. Teen drivers’ crashes and near-

crashes have increased sevenfold when dialing or reaching for a phone, and fourfold when sending or receiving a text message (Klauer et al., 2014). This risk difference also appeared when drivers were asked to pull off at a freeway rest stop 8 miles ahead. Of drivers conversing with a passenger, 88 percent did so. Of those talking on a cell phone, 50 percent drove on by (Strayer & Drews, 2007). And the increased risks are equal for handheld and hands-

free phones, indicating that the distraction effect is mostly cognitive rather than visual (Strayer & Watson, 2012).

Selective Inattention

inattentional blindness failing to see visible objects when our attention is directed elsewhere.

At the level of conscious awareness, we are “blind” to all but a tiny sliver of visual stimuli. To demonstrate this inattentional blindness, researchers showed people a one-

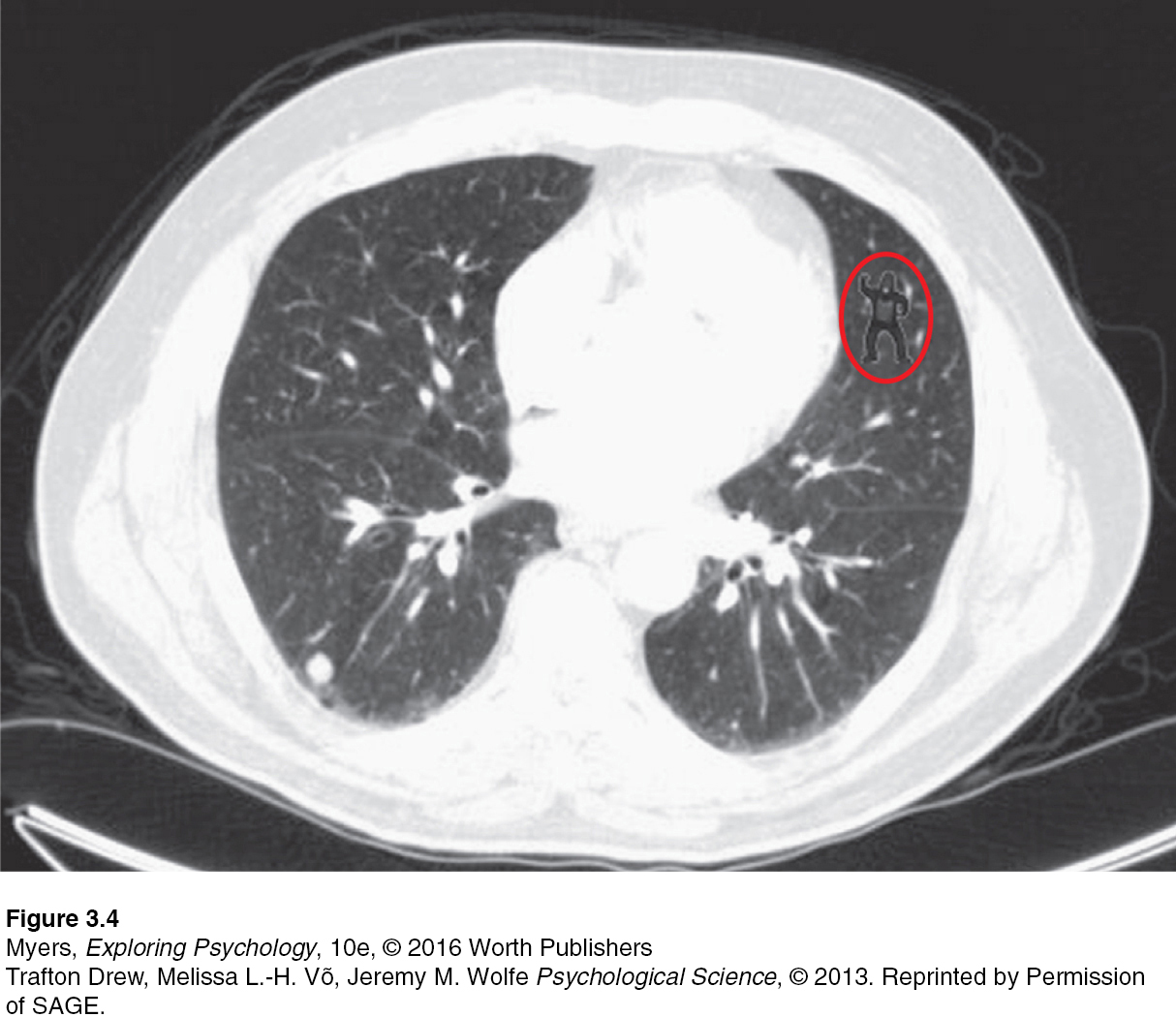

In a repeat of the experiment, smart-

Given that most people miss someone in a gorilla suit while their attention is riveted elsewhere, imagine the fun that magicians can have by manipulating our selective attention. Misdirect people’s attention and they will miss the hand slipping into the pocket. “Every time you perform a magic trick, you’re engaging in experimental psychology,” says magician Teller (2009), a master of mind-

change blindness failing to notice changes in the environment.

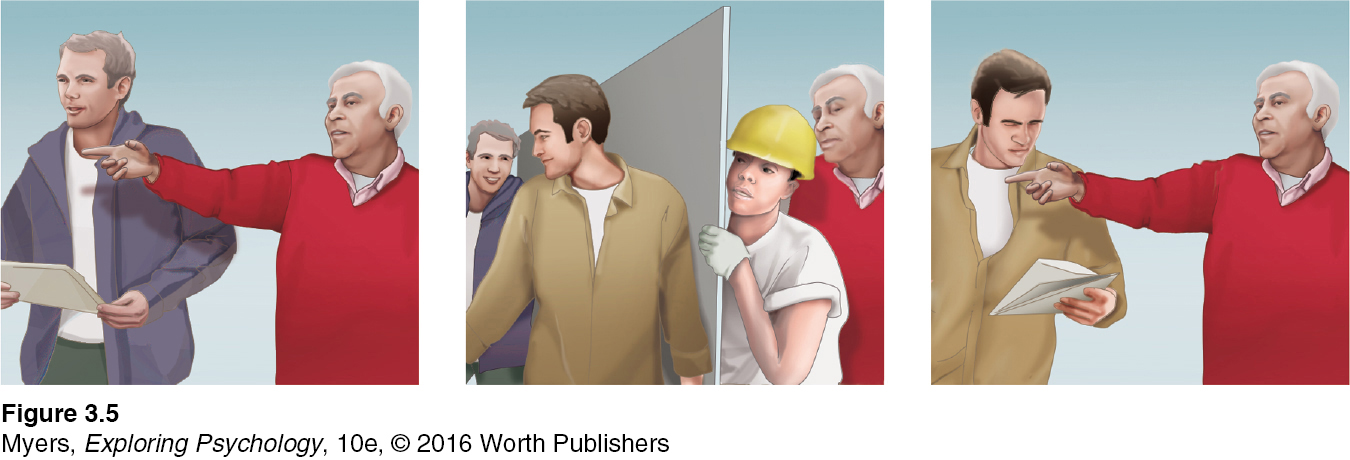

Magicians also exploit our change blindness. Participants in laboratory experiments on change blindness have failed to notice that, after a brief visual interruption, a big Coke bottle had disappeared, a railing had risen, or clothing color had changed (Chabris & Simons, 2010; Resnick et al., 1997). Two-

With this forewarning, are you still vulnerable to change blindness? To find out, watch the 3-

With this forewarning, are you still vulnerable to change blindness? To find out, watch the 3-

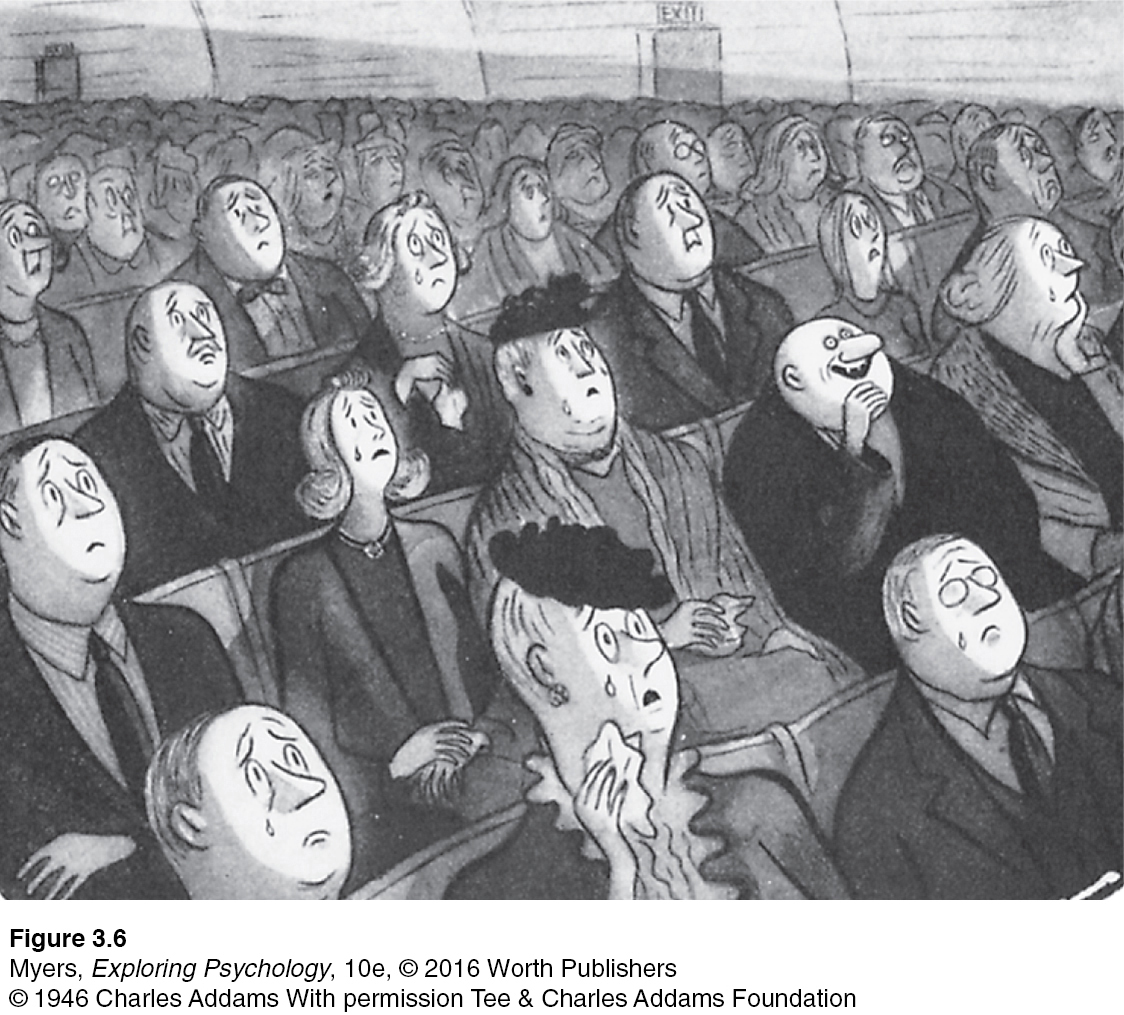

Some stimuli, however, are so powerful, so strikingly distinct, that we experience popout, as with the only smiling face in FIGURE 3.6. We don’t choose to attend to these stimuli; they draw our eye and demand our attention.

The dual-

RETRIEVE IT

Question

Explain three attentional principles that magicians may use to fool us.

Dual Processing: The Two-Track Mind

3-

Discovering which brain region becomes active with a particular conscious experience strikes many people as interesting, but not mind blowing. (If everything psychological is simultaneously biological, then our ideas, emotions, and spirituality must all, somehow, be embodied.) What is mind blowing to many of us is the growing evidence that we have, so to speak, two minds, each supported by its own neural equipment.

dual processing the principle that information is often simultaneously processed on separate conscious and unconscious tracks.

At any moment, we are aware of little more than what’s on the screen of our consciousness. But beneath the surface, unconscious information processing occurs simultaneously on many parallel tracks. When we look at a bird flying, we are consciously aware of the result of our cognitive processing (“It’s a hummingbird!”) but not of our subprocessing of the bird’s color, form, movement, and distance. One of the grand ideas of recent cognitive neuroscience is that much of our brain work occurs off stage, out of sight. Perception, memory, thinking, language, and attitudes all operate on two levels—

If you are a driver, consider how you move into a right lane. Drivers know this unconsciously but cannot accurately explain it (Eagleman, 2011). Most say they would bank to the right, then straighten out—

blindsight a condition in which a person can respond to a visual stimulus without consciously experiencing it.

Or consider this story, which illustrates how science can be stranger than science fiction. During my sojourns at Scotland’s University of St Andrews, I [DM] came to know cognitive neuroscientists David Milner and Melvyn Goodale (2008). A local woman, whom they called D. F., suffered brain damage when overcome by carbon monoxide, leaving her unable to recognize and discriminate objects visually. Consciously, D. F. could see nothing. Yet she exhibited blindsight—she acted as though she could see. Asked to slip a postcard into a vertical or horizontal mail slot, she could do so without error. Asked the width of a block in front of her, she was at a loss, but she could grasp it with just the right finger-

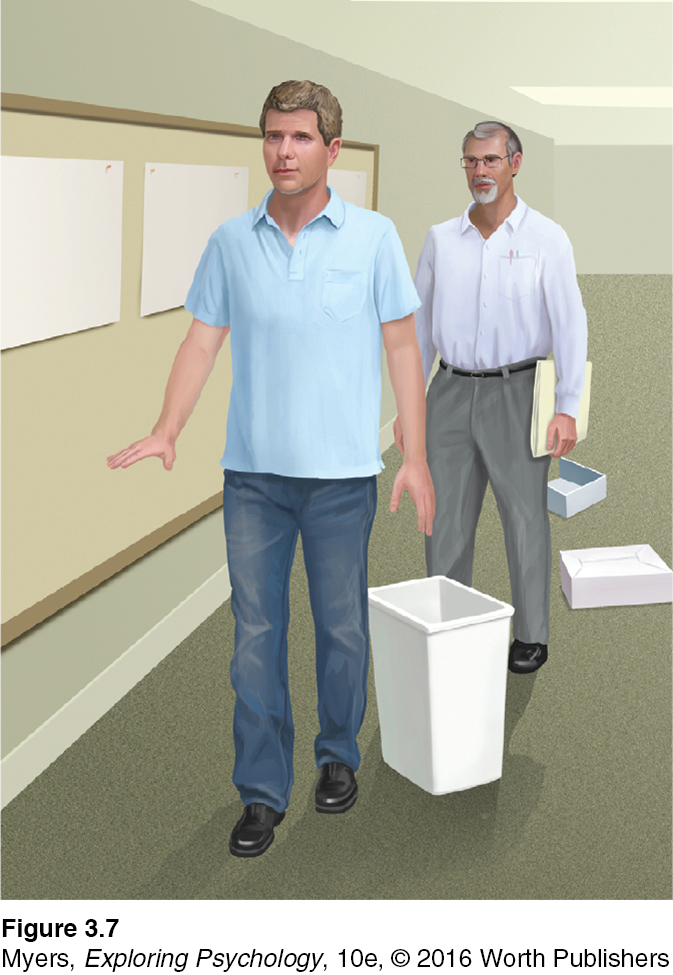

How could this be? Don’t we have one visual system? Goodale and Milner knew from animal research that the eye sends information simultaneously to different brain areas, which support different tasks (Weiskrantz, 2009, 2010). Sure enough, a scan of D. F.’s brain activity revealed normal activity in the area concerned with reaching for, grasping, and navigating objects, but damage in the area concerned with consciously recognizing objects. (See another example in FIGURE 3.7.)

How strangely intricate is this thing we call vision, conclude Goodale and Milner in their aptly titled book, Sight Unseen (2004). We may think of our vision as a single system that controls our visually guided actions. Actually, it is a dual-

The dual-

People often have trouble accepting that much of our everyday thinking, feeling, and acting operates outside our conscious awareness (Bargh & Chartrand, 1999). Some “80 to 90 percent of what we do is unconscious,” says Nobel Laureate and memory expert Eric Kandel (2008). We are understandably inclined to believe that our intentions and deliberate choices rule our lives. But consciousness, though enabling us to exert voluntary control and to communicate our mental states to others, is but the tip of the information-

To think further about conscious awareness and decision making, visit LaunchPad’s Psych-

To think further about conscious awareness and decision making, visit LaunchPad’s Psych-

parallel processing the processing of many aspects of a problem simultaneously; the brain’s natural mode of information processing for many functions.

Parallel processing enables your mind to take care of routine business. Unconscious parallel processing is faster than conscious sequential processing, but both are essential. Sequential processing is best for solving new problems, which requires your focused attention. Try this: If you are right-

RETRIEVE IT

Question

What are the mind's two tracks, and what is dual processing?

REVIEW Consciousness: Some Basic Concepts

Learning Objectives

Test Yourself by taking a moment to answer each of these Learning Objective Questions (repeated here from within the chapter). Research suggests that trying to answer these questions on your own will improve your long-

Question

3-

Question

3-

Question

3-

Terms and Concepts to Remember

Test yourself on these terms.

Question

consciousness (p. 82) cognitive neuroscience (p. 83) selective attention (p. 83) inattentional blindness (p. 84) change blindness (p. 85) dual processing (p. 87) blindsight (p. 87) parallel processing (p. 88) | failing to see visible objects when our attention is directed elsewhere. our awareness of ourselves and our environment. a condition in which a person can respond to a visual stimulus without consciously experiencing it. the principle that information is often simultaneously processed on separate conscious and unconscious tracks. the processing of many aspects of a problem simultaneously; the brain's natural mode of information processing for many functions. the focusing of conscious awareness on a particular stimulus. failing to notice changes in the environment. the interdisciplinary study of the brain activity linked with cognition (including perception, thinking, memory, and language). |

Experience the Testing Effect

Test yourself repeatedly throughout your studies. This will not only help you figure out what you know and don’t know; the testing itself will help you learn and remember the information more effectively thanks to the testing effect.

Question 3.1

1. Failure to see visible objects because our attention is occupied elsewhere is called .

Question 3.2

2. We register and react to stimuli outside of our awareness by means of processing. When we devote deliberate attention to stimuli, we use processing.

Question 3.3

3. blindness and change blindness are forms of selective attention.

Use  to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in

to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in  .

.