3.2 Sleep and Dreams

3-

sleep periodic, natural loss of consciousness—

Sleep—the irresistible tempter to whom we inevitably succumb. Sleep—

Now, by recording the brain waves and muscle movements of sleeping participants, and by observing and occasionally waking them, researchers are solving some of sleep’s deepest mysteries. Perhaps you can anticipate some of their discoveries. Are the following statements true or false?

When people dream of performing some activity, their limbs often move in concert with the dream.

Older adults sleep more than young adults.

Sleepwalkers are acting out their dreams.

Sleep experts recommend treating insomnia with an occasional sleeping pill.

Some people dream every night; others seldom dream.

All these statements (adapted from Palladino & Carducci, 1983) are false. To see why, read on.

“I love to sleep. Do you? Isn’t it great? It really is the best of both worlds. You get to be alive and unconscious.”

Comedian Rita Rudner, 1993

Biological Rhythms and Sleep

Like the ocean, life has its rhythmic tides. Over varying time periods, our bodies fluctuate, and with them, our minds. Let’s look more closely at two of those biological rhythms—

Circadian Rhythm

3-

circadian [ser-

The rhythm of the day parallels the rhythm of life—

Some students sleep like the fellow who stayed up all night to see where the Sun went. (Then it dawned on him.)

Age and experience can alter our circadian rhythm. Most 20-

Sleep Stages

3-

Sooner or later, sleep overtakes us and consciousness fades as different parts of our brain’s cortex stop communicating (Massimini et al., 2005). Yet the sleeping brain remains active and has its own biological rhythm.

REM sleep rapid eye movement sleep; a recurring sleep stage during which vivid dreams commonly occur. Also known as paradoxical sleep, because the muscles are relaxed (except for minor twitches) but other body systems are active.

About every 90 minutes, you cycle through four distinct sleep stages. This fact came to light after 8-

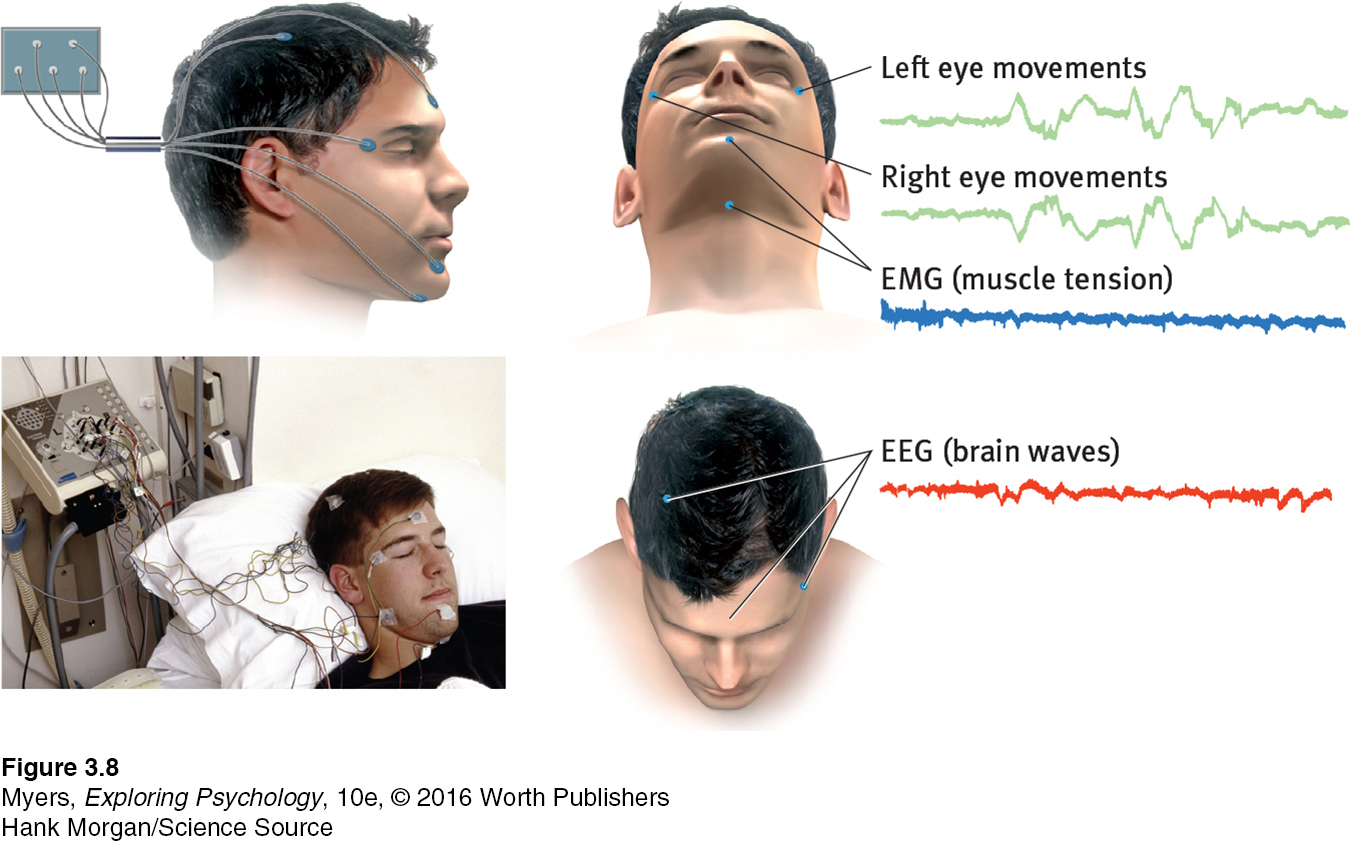

Similar procedures used with thousands of volunteers showed the cycles were a normal part of sleep (Kleitman, 1960). To appreciate these studies, imagine yourself as a participant. As the hour grows late, you feel sleepy and yawn in response to reduced brain metabolism. (Yawning, which is also socially contagious, stretches your neck muscles and increases your heart rate, which increases your alertness [Moorcroft, 2003].) When you are ready for bed, a researcher comes in and tapes electrodes to your scalp (to detect your brain waves), on your chin (to detect muscle tension), and just outside the corners of your eyes (to detect eye movements) (FIGURE 3.8). Other devices will record your heart rate, respiration rate, and genital arousal.

Dolphins, porpoises, and whales sleep with one side of their brain at a time (Miller et al., 2008).

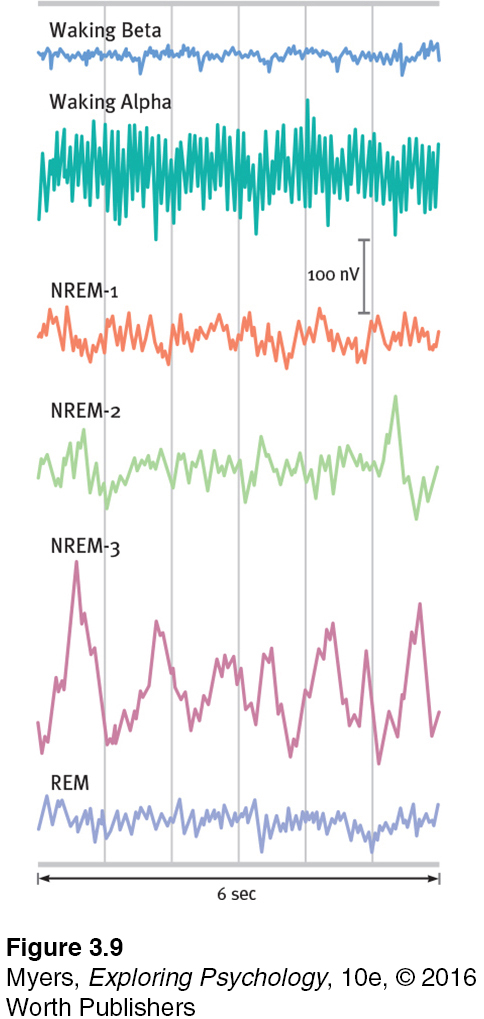

alpha waves the relatively slow brain waves of a relaxed, awake state.

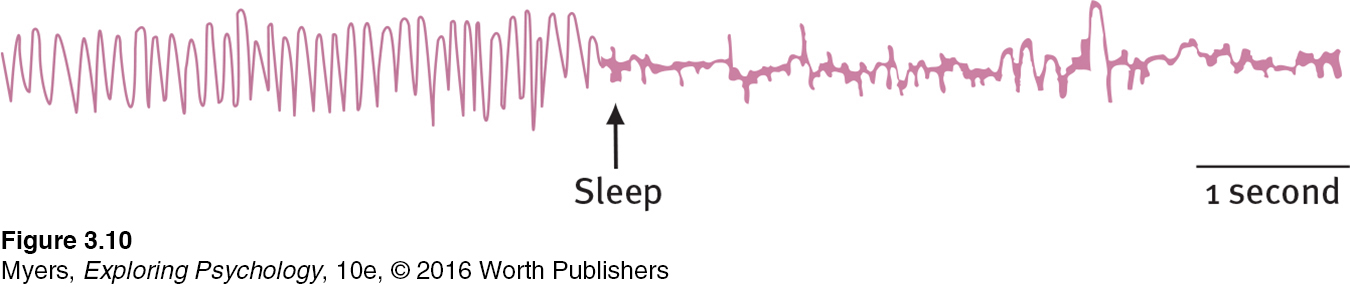

When you are in bed with your eyes closed, the researcher in the next room sees on the EEG the relatively slow alpha waves of your awake but relaxed state (FIGURE 3.9). As you adapt to all this equipment, you grow tired and, in an unremembered moment, slip into sleep (FIGURE 3.10). The transition is marked by the slowed breathing and the irregular brain waves of non-

In one of his 15,000 research participants, William Dement (1999) observed the moment the brain’s perceptual window to the outside world slammed shut. Dement asked this sleep-

hallucinations false sensory experiences, such as seeing something in the absence of an external visual stimulus.

During this brief NREM-

To catch your own hypnagogic experiences, you might use your alarm’s snooze function.

You then relax more deeply and begin about 20 minutes of NREM-

To better understand EEG readings and their relationship to consciousness, sleep, and dreams, experience the tutorial and simulation at LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: EEG and Sleep Stages.

To better understand EEG readings and their relationship to consciousness, sleep, and dreams, experience the tutorial and simulation at LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: EEG and Sleep Stages.

delta waves the large, slow brain waves associated with deep sleep.

Then you transition to the deep sleep of NREM-

REM Sleep

About an hour after you first fall asleep, a strange thing happens. Rather than continuing in deep slumber, you ascend from your initial sleep dive. Returning through NREM-

People rarely snore during dreams. When REM starts, snoring stops.

Except during very scary dreams, your genitals become aroused during REM sleep. You have an erection or increased vaginal lubrication and clitoral engorgement, regardless of whether the dream’s content is sexual (Karacan et al., 1966). Men’s common “morning erection” stems from the night’s last REM period, often just before waking. In young men, sleep-

Your brain’s motor cortex is active during REM sleep, but your brainstem blocks its messages. This leaves your muscles relaxed, so much so that, except for an occasional finger, toe, or facial twitch, you are essentially paralyzed. Moreover, you cannot easily be awakened. REM sleep is thus sometimes called paradoxical sleep: The body is internally aroused, with waking-

Horses, which spend 92 percent of each day standing and can sleep standing, must lie down for REM sleep (Morrison, 2003).

RETRIEVE IT

Question

Why would communal sleeping provide added protection for those whose safety depends upon vigilance, such as these soldiers?

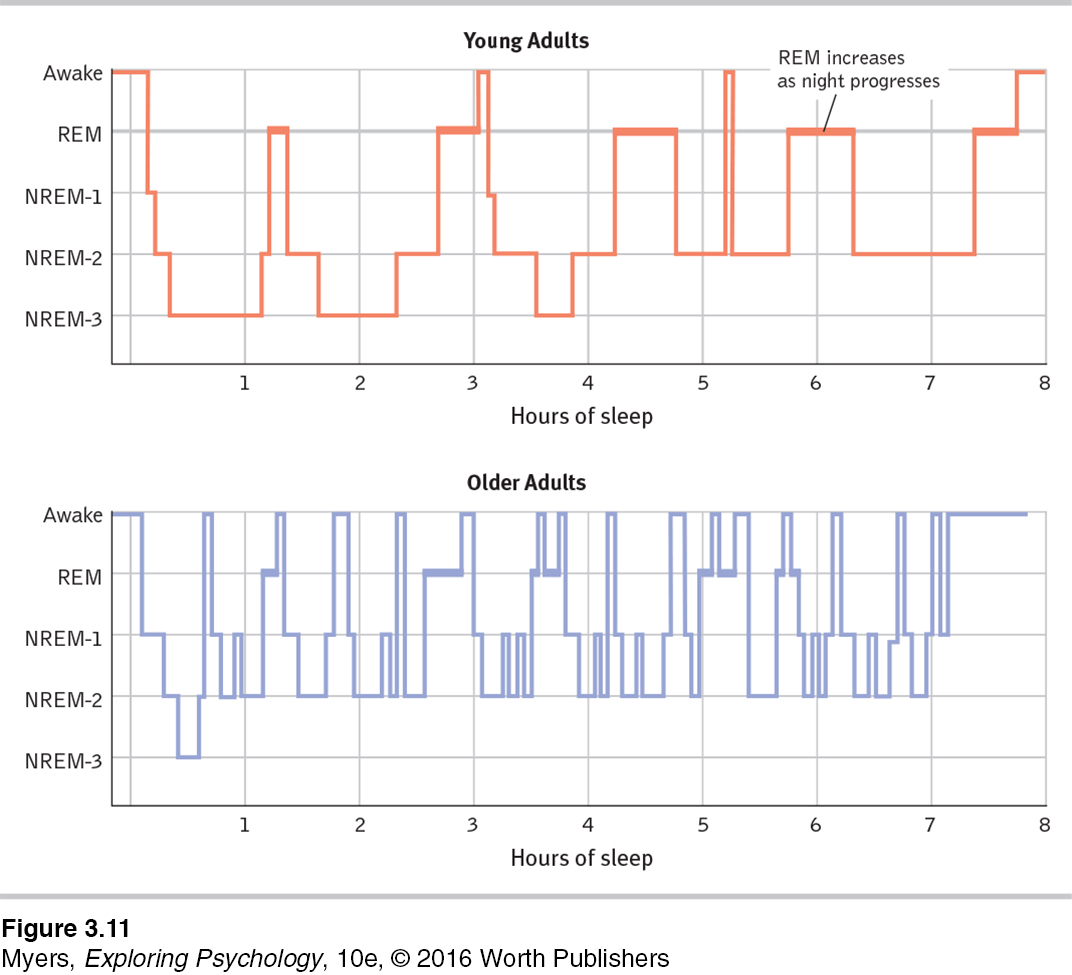

The sleep cycle repeats itself about every 90 minutes for younger adults (somewhat more frequently for older adults). As the night wears on, deep NREM-

RETRIEVE IT

Question

What are the four sleep stages, and in what order do we normally travel through those stages?

Can you match the cognitive experience with the sleep stage?

Question

NREM- NREM- REM | minimal awareness fleeting images story- |

What Affects Our Sleep Patterns?

3-

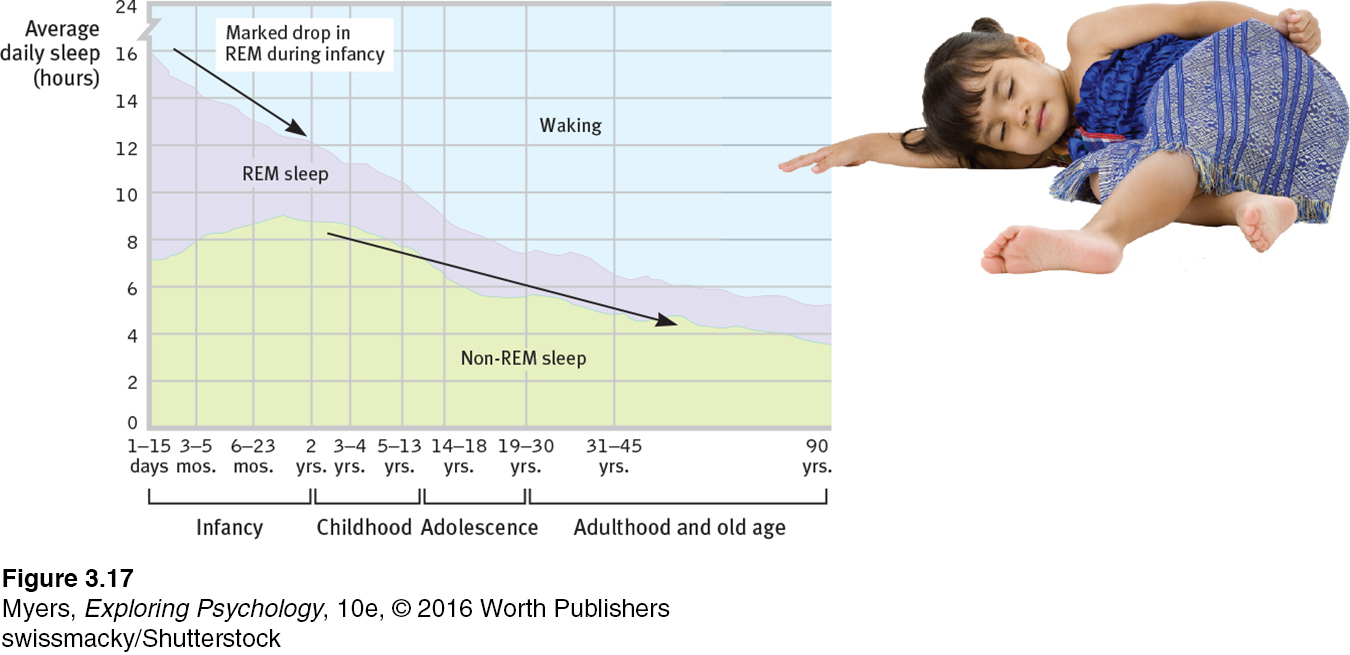

The idea that “everyone needs 8 hours of sleep” is untrue. To know how much sleep people need, the first clue is their age. Newborns often sleep two-

Canadian, American, British, German, and Japanese adults average 6½ to 7 hours of sleep on workdays and 7 to 8 hours on other days (National Sleep Foundation, 2013). Thanks to modern lighting, shift work, and social media diversions, many who would have gone to bed at 9:00 P.M. a century ago are now up until 11:00 P.M. or later. With sleep, as with waking behavior, biology and environment interact.

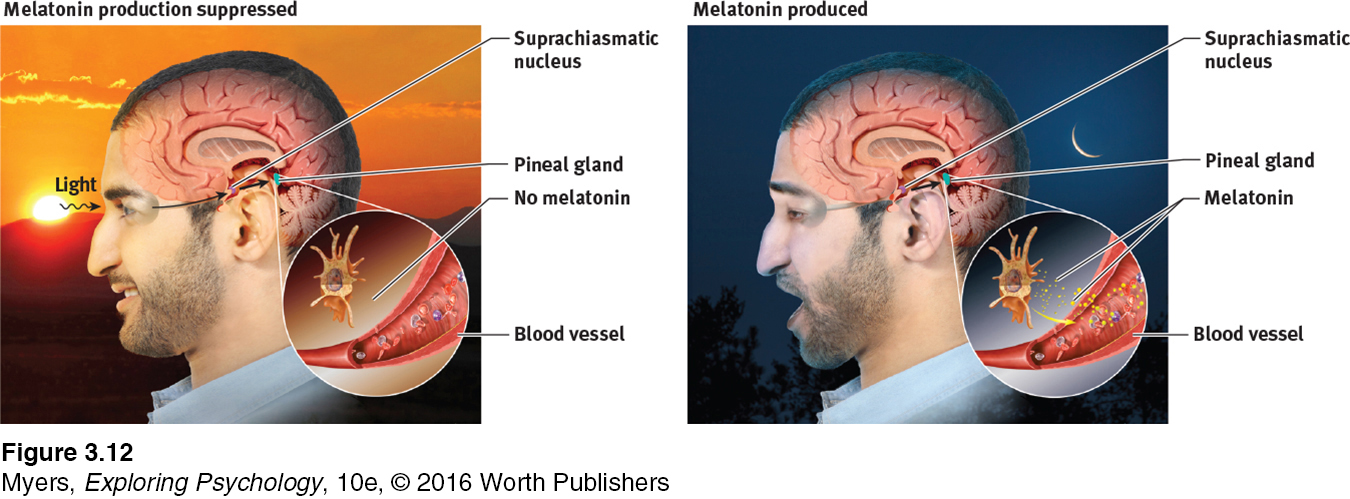

suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) a pair of cell clusters in the hypothalamus that controls circadian rhythm. In response to light, the SCN causes the pineal gland to adjust melatonin production, thus modifying our feelings of sleepiness.

Being bathed in (or deprived of) light disrupts our 24-

A circadian disadvantage: One study of a decade’s 24,121 Major League Baseball games found that teams who had crossed three time zones before playing a multiday series had nearly a 60 percent chance of losing their first game (Winter et al., 2009).

Sleep often eludes those who stay up late and sleep in on weekends, and then go to bed earlier on Sunday to prepare for the week ahead (Oren & Terman, 1998). For North Americans who fly to Europe and need to be up when their circadian rhythm cries “SLEEP,” bright light (spending the next day outdoors) helps reset the biological clock (Czeisler et al., 1986, 1989; Eastman et al., 1995).

RETRIEVE IT

Question

The nucleus helps monitor the brain's release of melatonin, which affects our rhythm.

Why Do We Sleep?

3-

So, our sleep patterns differ from person to person. But why do we have this need for sleep? Psychologists offer five possible reasons.

Sleep protects. When darkness shut down the day’s hunting, food gathering, and travel, our distant ancestors were better off asleep in a cave, out of harm’s way. Those who didn’t try to navigate around dark cliffs were more likely to leave descendants. This fits a broader principle: A species’ sleep pattern tends to suit its ecological niche (Siegel, 2009). Animals with the greatest need to graze and the least ability to hide tend to sleep less. Animals also sleep less, with no ill effects, during times of mating and migration (Siegel, 2012). (For a sampling of animal sleep times, see FIGURE 3.13.)

Page 93

"Sleep faster, we need the pillows."

Yiddish proverb

"Corduroy pillows make headlines."

Anonymous

Sleep helps us recuperate. Sleep helps restore the immune system and repair brain tissue. Bats and other animals with high waking metabolism burn a lot of calories, producing a lot of free radicals, molecules that are toxic to neurons. Sleeping a lot gives resting neurons time to repair themselves, while pruning or weakening unused connections (Gilestro et al., 2009; Tononi & Cirelli, 2013). Sleep also enables house cleaning. Studies of mice show that sleep sweeps the brain of toxic metabolic waste products (Xie et al., 2013). Think of it this way: When consciousness leaves your house, workers come in for a makeover, saying “Good night. Sleep tidy.”

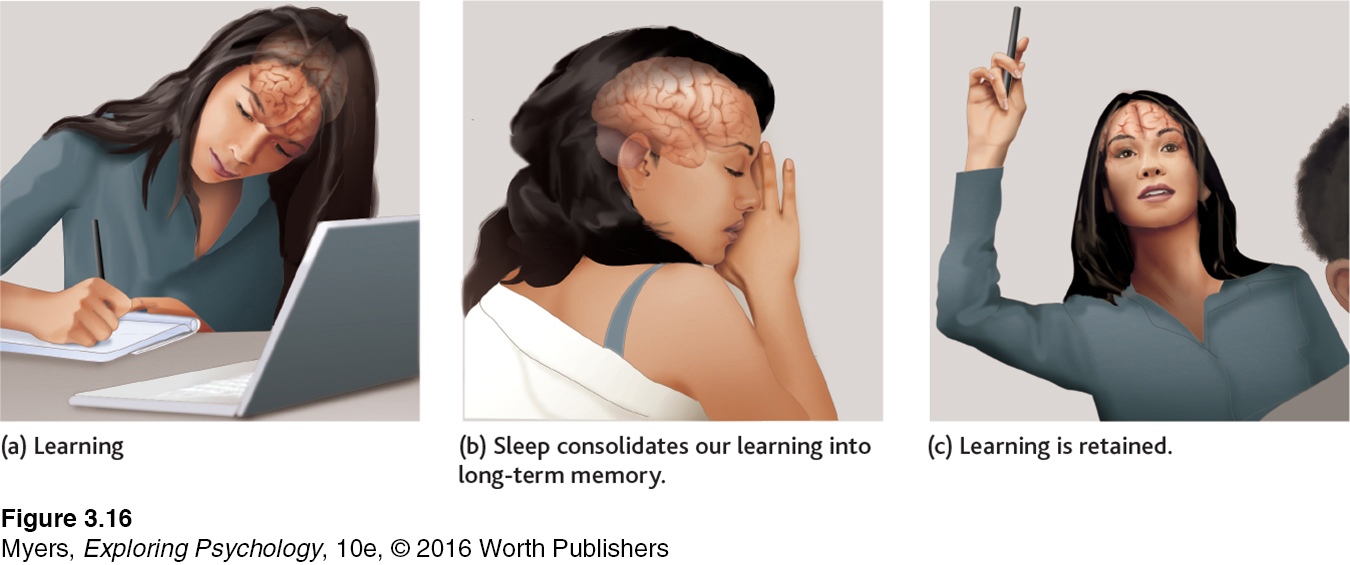

Sleep helps restore and rebuild our fading memories of the day’s experiences. Sleep consolidates our memories. It replays or “reactivates” recent learning and strengthens its neural connections (Yang et al., 2014). Sleep also shifts experiences stored in the hippocampus to permanent storage elsewhere in the cortex (Diekelmann & Born, 2010; Racsmány et al., 2010). Adults and children trained to perform tasks therefore recall them better after a night’s sleep, or even after a short nap, than after several hours awake (Friedrich et al., 2015; Kurdziel et al., 2013; Stickgold & Ellenbogen, 2008). After sleeping well, older people remember more of recently learned material (Drummond, 2010). Sleep, it seems, strengthens memories in a way that being awake does not.

Sleep feeds creative thinking. Dreams can inspire noteworthy artistic and scientific achievements, such as the dreams that clued chemist August Kekulé to the structure of benzene (Ross, 2006) and inspired medical researcher Carl Alving (2011) to invent the vaccine patch. More commonplace is the boost that a complete night’s sleep gives to our thinking and learning. After working on a task, then sleeping on it, people solve difficult problems more insightfully than do those who stay awake (Barrett, 2011; Sio et al., 2013). They also are better at spotting connections among novel pieces of information (Ellenbogen et al., 2007). To think smart and see connections, it often pays to ponder a problem just before bed and then sleep on it.

Sleep supports growth. During deep sleep, the pituitary gland releases a growth hormone that is necessary for muscle development. A regular full night’s sleep can also “dramatically improve your athletic ability,” report James Maas and Rebecca Robbins (2010). Well-

rested athletes have faster reaction times, more energy, and greater endurance. Teams that build 8 to 10 hours of daily sleep into their training show improved performance.

Given all the benefits of sleep, it’s no wonder that sleep loss hits us so hard.

RETRIEVE IT

Question

What are five proposed reasons for our need for sleep?

Sleep Deprivation and Sleep Disorders

3-

When our body yearns for sleep but does not get it, we begin to feel terrible. Trying to stay awake, we will eventually lose. In the tiredness battle, sleep always wins.

Effects of Sleep Loss

Today, more than ever, our sleep patterns leave us not only sleepy but drained of energy and feelings of well-

In 1989, Michael Doucette was named America’s Safest Driving Teen. In 1990, while driving home from college, he fell asleep at the wheel and collided with an oncoming car, killing both himself and the other driver. Michael’s driving instructor later acknowledged never having mentioned sleep deprivation and drowsy driving (Dement, 1999).

Obviously, then, we need sleep. Sleep commands roughly one-

College and university students are especially sleep deprived; 69 percent in one national survey reported “feeling tired” or “having little energy” on at least several days during the last two weeks (AP, 2009). This trend toward tiredness has increased in recent years, causing some researchers to label current times as the “Great Sleep Recession” (Keyes et al., 2015). For students, less sleep also predicts more conflicts in friendships and romantic relationships (Gordon & Chen, 2014; Tavernier & Willoughby, 2014). Tired triggers crabbiness. In another survey, 28 percent of high school students acknowledged falling asleep in class at least once a week (National Sleep Foundation, 2006). The going needn’t get boring before students start snoring.

To see whether you are one of the many sleep-

To see whether you are one of the many sleep-

In a 2013 Gallup poll, 40 percent of Americans reported getting 6 hours or less sleep a night (Jones, 2013).

“You wake up in the middle of the night and grab your smartphone to check the time—

Nick Bilton, “Disruptions: For a Restful Night, Make Your Smartphone Sleep on the Couch,” 2014

Sleep loss is also a predictor of depression. Researchers who studied 15,500 12-

Sleep-

“Remember to sleep because you have to sleep to remember.”

James B. Maas and Rebecca S. Robbins, Sleep for Success, 2010

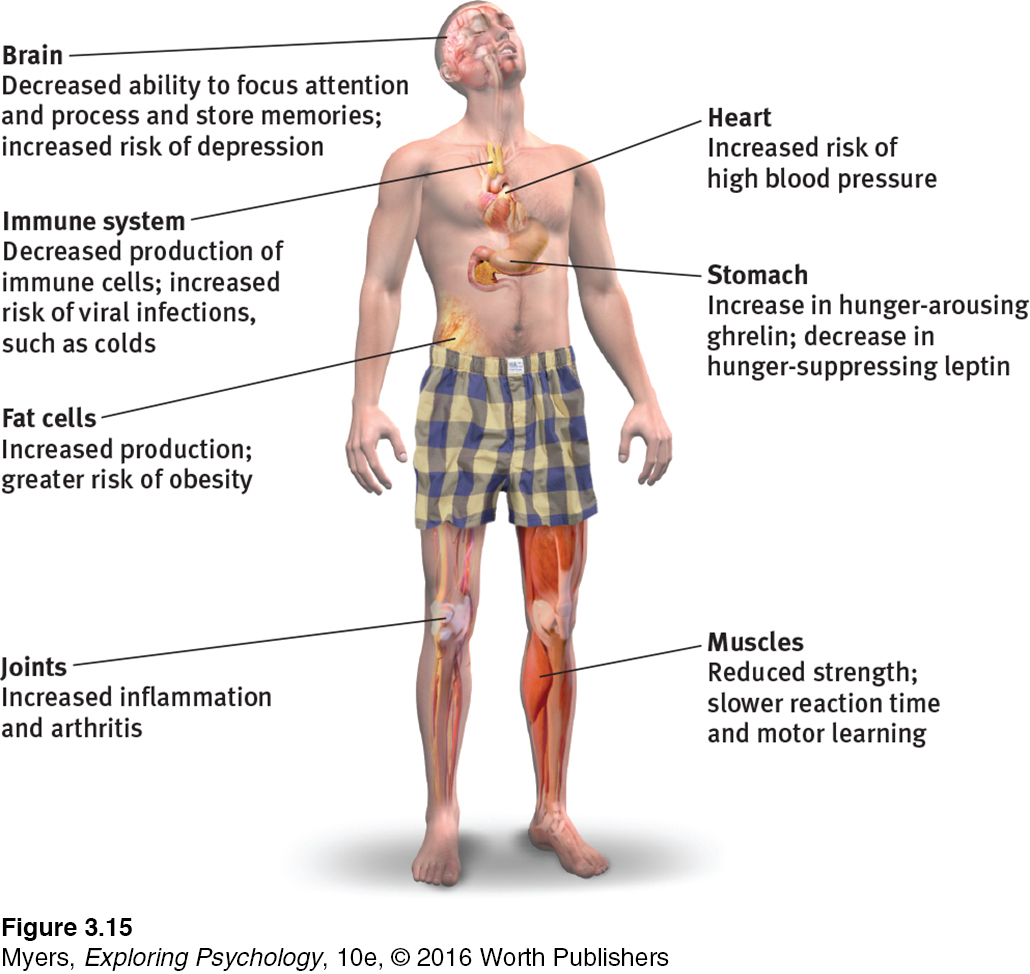

Lack of sleep can also make you gain weight. Sleep deprivation

increases ghrelin, a hunger-

arousing hormone, and decreases its hunger- suppressing partner, leptin (Shilsky et al., 2012). decreases metabolic rate, a gauge of energy use (Buxton et al., 2012).

increases cortisol, a stress hormone that stimulates the body to make fat.

enhances limbic brain responses to the mere sight of food and decreases cortical inhibition (Benedict et al., 2012; Greer et al., 2013; St-

Onge et al., 2012).

Thus, children and adults who sleep less are fatter than average, and in recent decades people have been sleeping less and weighing more (Shiromani et al., 2012). Moreover, experimental sleep deprivation increases appetite and eating; our tired brains find fatty foods more enticing (Fang et al., 2015; Nixon et al., 2008; Patel et al., 2006; Spiegel et al., 2004; Van Cauter et al., 2007). So, sleep loss helps explain the weight gain common among sleep-

Sleep also affects our physical health. When infections do set in, we typically sleep more, boosting our immune cells. Sleep deprivation can suppress the immune cells that battle viral infections and cancer (Möller-

Sleep deprivation slows reactions and increases errors on visual attention tasks similar to those involved in screening airport baggage, performing surgery, and reading X-

“So shut your eyes

Kiss me goodbye

And sleep

Just sleep.”

Sleep by My Chemical Romance

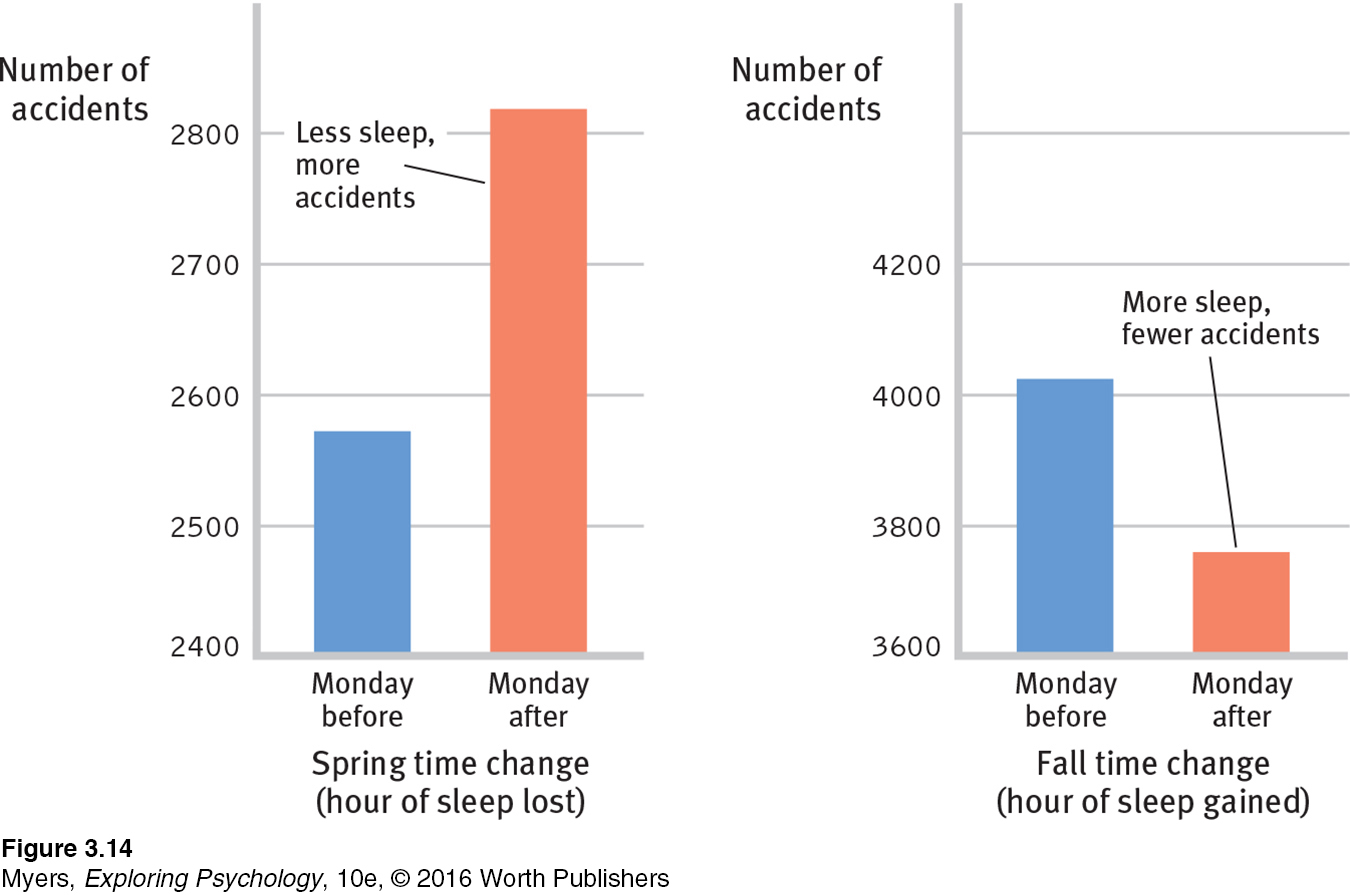

Stanley Coren capitalized on what is, for many North Americans, a semi-

IMMERSIVE LEARNING Consider how researchers have addressed these issues in LaunchPad's How Would You Know If Sleep Deprivation Affects Academic Performance?

IMMERSIVE LEARNING Consider how researchers have addressed these issues in LaunchPad's How Would You Know If Sleep Deprivation Affects Academic Performance?

FIGURE 3.15 summarizes the effects of sleep deprivation. But there is good news! Psychologists have discovered a treatment that strengthens memory, increases concentration, boosts mood, moderates hunger, reduces obesity, fortifies the immune system, and lessens the risk of fatal accidents. Even better news: The treatment feels good, it can be self-

Major Sleep Disorders

insomnia recurring problems in falling or staying asleep.

No matter what their normal need for sleep, 1 in 10 adults, and 1 in 4 older adults, complain of insomnia—persistent problems in either falling or staying asleep (Irwin et al., 2006). The result is tiredness and increased risk of depression (Baglioni et al., 2011). All of us, when anxious or excited, may have trouble sleeping. (And smart phones under the pillow and used as alarm clocks increase the likelihood of disrupted sleep.) From middle age on, awakening occasionally during the night becomes the norm, not something to fret over or treat with medication (Vitiello, 2009). Ironically, insomnia is worsened by fretting about it. In laboratory studies, people who think they have insomnia do sleep less than others. But they typically overestimate how long it takes them to fall asleep and underestimate how long they actually have slept (Harvey & Tang, 2012). Even if we have been awake only an hour or two, we may think we have had very little sleep because it’s the waking part we remember.

The most common quick fixes for true insomnia—

Some Natural Sleep Aids

|

“The lion and the lamb shall lie down together, but the lamb will not be very sleepy.”

Woody Allen, in the movie Love and Death, 1975

narcolepsy a sleep disorder characterized by uncontrollable sleep attacks. The sufferer may lapse directly into REM sleep, often at inopportune times.

Falling asleep is not the problem for people with narcolepsy (from the Greek narke, “numbness,” and lepsis, “seizure”), who have sudden attacks of overwhelming sleepiness, usually lasting less than 5 minutes. Narcolepsy attacks can occur at the most inopportune times, often triggered by strong emotions—

“Sleep is like love or happiness. If you pursue it too ardently it will elude you.”

Wilse Webb, Sleep: The Gentle Tyrant, 1992

sleep apnea a sleep disorder characterized by temporary cessations of breathing during sleep and repeated momentary awakenings.

Although 1 in 20 of us have sleep apnea, it was unknown before modern sleep research. Apnea means “with no breath,” and people with this condition intermittently stop breathing during sleep. After an airless minute or so, decreased blood oxygen arouses them enough to snort in air for a few seconds, in a process that repeats hundreds of times each night, depriving them of slow-

Sleep apnea is associated with obesity, and as the number of obese Americans has increased, so has sleep apnea, particularly among overweight men (Keller, 2007). Apnea-

night terrors a sleep disorder characterized by high arousal and an appearance of being terrified; unlike nightmares, night terrors occur during NREM-

Unlike sleep apnea, night terrors target mostly children, who may sit up or walk around, talk incoherently, experience doubled heart and breathing rates, and appear terrified while asleep (Hartmann, 1981). They seldom wake up fully during an episode and recall little or nothing the next morning—

Sleepwalking—

RETRIEVE IT

Question

A well-

Dreams

Now playing at an inner theater near you: the premiere showing of a sleeping person’s vivid dream. This never-

Waking from a troubling dream (you were late to something and your legs weren’t working), who among us has not wondered about this weird state of consciousness? How can our brain so creatively, colorfully, and completely construct this alternative world? In the shadowland between our dreaming and waking consciousness, we may even wonder for a moment which is real.

Discovering the link between REM sleep and dreaming ushered in a new era in dream research. Instead of relying on someone’s hazy recall hours or days after having a dream, researchers could catch dreams as they happened. They could awaken people during or within 3 minutes after a REM sleep period and hear a vivid account.

What We Dream

3-

dream a sequence of images, emotions, and thoughts passing through a sleeping person’s mind.

Daydreams tend to involve the familiar detailsof our life—

“I do not believe that I am now dreaming, but I cannot prove that I am not.”

Philosopher Bertrand Russell (1872-

We spend 6 years of our life in dreams, many of which are anything but sweet. For both women and men, 8 in 10 dreams are marked by at least one negative event or emotion (Domhoff, 2007). Common themes include repeatedly failing in an attempt to do something; being attacked, pursued, or rejected; or experiencing misfortune (Hall et al., 1982). Dreams with sexual imagery occur less often than you might think. In one study, only 1 in 10 dreams among young men and 1 in 30 among young women had sexual content (Domhoff, 1996).

More commonly, a dream’s story line incorporates traces of previous days’ nonsexual experiences and preoccupations (De Koninck, 2000):

After suffering a trauma, people commonly report nightmares, which help extinguish daytime fears (Levin & Nielsen, 2007, 2009). One sample of Americans recording their dreams during September, 2001 reported an increase in threatening dreams following the 9/11 terrorist attacks (Propper et al., 2007).

“For what one has dwelt on by day, these things are seen in visions of the night.”

Menander of Athens (342–

Compared with city dwellers, people in hunter-

gatherer societies more often dream of animals (Mestel, 1997). Compared with nonmusicians, musicians report twice as many dreams of music (Uga et al., 2006). Studies in four countries have found blind people mostly dreaming of using their nonvisual senses (Buquet, 1988; Taha, 1972; Vekassy, 1977). But even natively blind people sometimes “see” in their dreams (Bértolo, 2005). Likewise, people born paralyzed below the waist sometimes dream of walking, standing, running, or cycling (Saurat et al., 2011; Voss et al., 2011).

Our two-

A popular sleep myth: If you dream you are falling and hit the ground (or if you dream of dying), you die. Unfortunately, those who could confirm these ideas are not around to do so. Many people, however, have had such dreams and are alive to report them.

So, could we learn a foreign language by hearing it played while we sleep? If only. While sleeping, we can learn to associate a sound with a mild electric shock (and to react to the sound accordingly). We can also learn to associate a particular sound with a pleasant or unpleasant odor (Arzi et al., 2012). But we do not remember recorded information played while we are soundly asleep (Eich, 1990; Wyatt & Bootzin, 1994). In fact, anything that happens during the 5 minutes just before we fall asleep is typically lost from memory (Roth et al., 1988). This explains why sleep apnea patients, who repeatedly awaken with a gasp and then immediately fall back to sleep, do not recall the episodes. Ditto someone who awakens momentarily, sends a text message, and the next day can’t remember doing so. It also explains why dreams that momentarily awaken us are mostly forgotten by morning. To remember a dream, get up and stay awake for a few minutes.

“Follow your dreams, except for that one where you’re naked at work.”

Attributed to comedian Henny Youngman

Why We Dream

3-

Dream theorists have proposed several explanations of why we dream, including these five:

manifest content according to Freud, the remembered story line of a dream (as distinct from its latent, or hidden, content).

latent content according to Freud, the underlying meaning of a dream (as distinct from its manifest content).

To satisfy our own wishes. In 1900, in his landmark book The Interpretation of Dreams, Sigmund Freud offered what he thought was “the most valuable of all the discoveries it has been my good fortune to make.” He proposed that dreams provide a psychic safety valve that discharges otherwise unacceptable feelings. He viewed a dream’s manifest content (the apparent and remembered story line) as a censored, symbolic version of its latent content, the unconscious drives and wishes that would be threatening if expressed directly. Although most dreams have no overt sexual imagery, Freud nevertheless believed that most adult dreams could be “traced back by analysis to erotic wishes.” Thus, a gun might be a disguised representation of a penis.

“When people interpret [a dream] as if it were meaningful and then sell those interpretations, it’s quackery.”

Sleep researcher J. Allan Hobson (1995)

Freud considered dreams the key to understanding our inner conflicts. However, his critics say it is time to wake up from Freud’s dream theory, which they regard as a scientific nightmare. Based on the accumulated science, “there is no reason to believe any of Freud’s specific claims about dreams and their purposes,” observed dream researcher William Domhoff (2003). Some contend that even if dreams are symbolic, they could be interpreted any way one wished. Others maintain that dreams hide nothing. A dream about a gun is a dream about a gun. Legend has it that even Freud, who loved to smoke cigars, acknowledged that “sometimes, a cigar is just a cigar.” Freud’s wish-

To file away memories. The information-

Brain scans confirm the link between REM sleep and memory. The brain regions that buzzed as rats learned to navigate a maze, or as people learned to perform a visual-

This is important news for students, many of whom, observed researcher Robert Stickgold (2000), suffer from a kind of sleep bulimia—

To develop and preserve neural pathways. Perhaps dreams, or the brain activity associated with REM sleep, serve a physiological function, providing the sleeping brain with periodic stimulation. This theory makes developmental sense. Stimulating experiences preserve and expand the brain’s neural pathways. Infants, whose neural networks are fast developing, spend much of their abundant sleep time in REM sleep (FIGURE 3.17).

Rapid eye movements also stir the liquid behind the cornea; this delivers fresh oxygen to corneal cells, preventing their suffocation.

To make sense of neural static. Other theories propose that dreams erupt from neural activation spreading upward from the brainstem (Antrobus, 1991; Hobson, 2003, 2004, 2009). According to “activation-

Question: Does eating spicy foods cause us to dream more?

Answer: Any food that causes you to awaken more increases your chance of recalling a dream (Moorcroft, 2003).

To reflect cognitive development. Some dream researchers dispute both the Freudian and neural activation theories, preferring instead to see dreams as part of brain maturation and cognitive development (Domhoff, 2010, 2011; Foulkes, 1999). For example, prior to age 9, children’s dreams seem more like a slide show and less like an active story in which the dreamer is an actor. Dreams overlap with waking cognition and feature coherent speech. They simulate reality by drawing on our concepts and knowledge. They engage brain networks that also are active during daydreaming—

REM rebound the tendency for REM sleep to increase following REM sleep deprivation.

TABLE 3.2 compares these major dream theories. Although today’s sleep researchers debate dreams’ functions—

Dream Theories

| Theory | Explanation | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Freud’s wish- |

Dreams preserve sleep and provide a “psychic safety valve”—expressing otherwise unacceptable feelings; contain manifest (remembered) content and a deeper layer of latent content (a hidden meaning). | Lacks any scientific support; dreams may be interpreted in many different ways. |

| Information- |

Dreams help us sort out the day’s events and consolidate our memories. | But why do we sometimes dream about things we have not experienced and about past events? |

| Physiological function | Regular brain stimulation from REM sleep may help develop and preserve neural pathways. | This does not explain why we experience meaningful dreams. |

| Neural activation | REM sleep triggers neural activity that evokes random visual memories, which our sleeping brain weaves into stories. | The individual’s brain is weaving the stories, which still tells us something about the dreamer. |

| Cognitive development | Dream content reflects dreamers’ level of cognitive development— |

Does not propose an adaptive function of dreams. |

So does this mean that because dreams serve physiological functions and extend normal cognition, they are psychologically meaningless? Not necessarily. Every psychologically meaningful experience involves an active brain. We are once again reminded of a basic principle: Biological and psychological explanations of behavior are partners, not competitors.

Dreams are a fascinating altered state of consciousness. But they are not the only altered state. As we will see next, drugs also alter conscious awareness.

RETRIEVE IT

Question

What five theories propose explanations for why we dream?

REVIEW Sleep and Dreams

Learning Objectives

Test Yourself by taking a moment to answer each of these Learning Objective Questions (repeated here from within the chapter). Research suggests that trying to answer these questions on your own will improve your long-

Question

3-

Question

3-

Question

3-

Question

3-

Question

3-

Question

3-

Question

3-

Question

3-

Terms and Concepts to Remember

Test yourself on these terms.

Question

sleep (p. 89) circadian [ser- REM sleep (p. 90) alpha waves (p. 91) hallucinations (p. 91) delta waves (p. 91) suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) (p. 94) insomnia (p. 98) narcolepsy (p. 99) sleep apnea (p. 99) night terrors (p. 100) dream (p. 101) manifest content (p. 102) latent content (p. 102) REM rebound (p. 104) | a sequence of images, emotions, and thoughts passing through a sleeping person's mind. a sleep disorder characterized by uncontrollable sleep attacks. The sufferer may lapse directly into REM sleep, often at inopportune times. rapid eye movement sleep; a recurring sleep stage during which vivid dreams commonly occur. Also known as paradoxical sleep, because the muscles are relaxed (except for minor twitches) but other body systems are active. the relatively slow brain waves of a relaxed, awake state. a sleep disorder characterized by temporary cessations of breathing during sleep and repeated momentary awakenings. according to Freud, the underlying meaning of a dream (as distinct from its manifest content). false sensory experiences, such as seeing something in the absence of an external visual stimulus. periodic, natural loss of consciousness— the large, slow brain waves associated with deep sleep. the tendency for REM sleep to increase following REM sleep deprivation. a sleep disorder characterized by high arousal and an appearance of being terrified; unlike nightmares, night terrors occur during NREM- recurring problems in falling or staying asleep. the biological clock; regular bodily rhythms (for example, of temperature and wakefulness) that occur on a 24- according to Freud, the remembered story line of a dream (as distinct from its latent, or hidden, content). a pair of cell clusters in the hypothalamus that controls circadian rhythm. In response to light, the SCN causes the pineal gland to adjust melatonin production, thus modifying our feelings of sleepiness. |

Experience the Testing Effect

Test yourself repeatedly throughout your studies. This will not only help you figure out what you know and don’t know; the testing itself will help you learn and remember the information more effectively thanks to the testing effect.

Question 3.4

1. Our body temperature tends to rise and fall in sync with a biological clock, which is referred to as .

Question 3.5

2. During the NREM-

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 3.6

3. The brain emits large, slow delta waves during sleep.

Question 3.7

4. As the night progresses, what happens to the REM stage of sleep?

Question 3.8

5. Which of the following is NOT one of the reasons that have been proposed to explain why we need sleep?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 3.9

6. What is the difference between narcolepsy and sleep apnea?

Question 3.10

7. In interpreting dreams, Freud was most interested in their

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 3.11

8. How has neural activation been used to explain why we dream?

Question 3.12

9. “For what one has dwelt on by day, these things are seen in visions of the night” (Menander of Athens, Fragments). How might the information-

Question 3.13

10. The tendency for REM sleep to increase following REM sleep deprivation is referred to as .

Use  to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in

to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in  .

.