4.1 Developmental Issues, Prenatal Development, and the Newborn

Developmental Psychology’s Major Issues

4-

developmental psychology a branch of psychology that studies physical, cognitive, and social change throughout the life span.

Researchers find human development interesting for the same reasons most of the rest of us do—

Nature and nurture: How does our genetic inheritance (our nature) interact with our experiences (our nurture) to influence our development? How have your nature and your nurture influenced your life story?

Continuity and stages: What parts of development are gradual and continuous, like riding an escalator? What parts change abruptly in separate stages, like climbing rungs on a ladder?

Stability and change: Which of our traits persist through life? How do we change as we age?

“Nature is all that a man brings with him into the world; nurture is every influence that affects him after his birth.”

Francis Galton,

English Men of Science, 1874

Nature and Nurture

The unique gene combination created when our mother’s egg engulfed our father’s sperm helped form us, as individuals. Genes predispose both our shared humanity and our individual differences.

But our experiences also shape us. Our families and peer relationships teach us how to think and act. Even differences initiated by our nature may be amplified by our nurture. We are not formed by either nature or nurture, but by the interaction between them. Biological, psychological, and social-

Mindful of how others differ from us, however, we often fail to notice the similarities stemming from our shared biology. Regardless of our culture, we humans share the same life cycle. We speak to our infants in similar ways and respond similarly to their coos and cries (Bornstein et al., 1992a,b). All over the world, the children of warm and supportive parents feel better about themselves and are less hostile than are the children of punishing and rejecting parents (Rohner, 1986; Scott et al., 1991). Although ethnic groups have differed in some ways, including average school achievement, the differences are “no more than skin deep.” To the extent that family structure, peer influences, and parental education predict behavior in one of these ethnic groups, they do so for the others as well. Compared with the person-

Continuity and Stages

Do adults differ from infants as a giant redwood differs from its seedling—

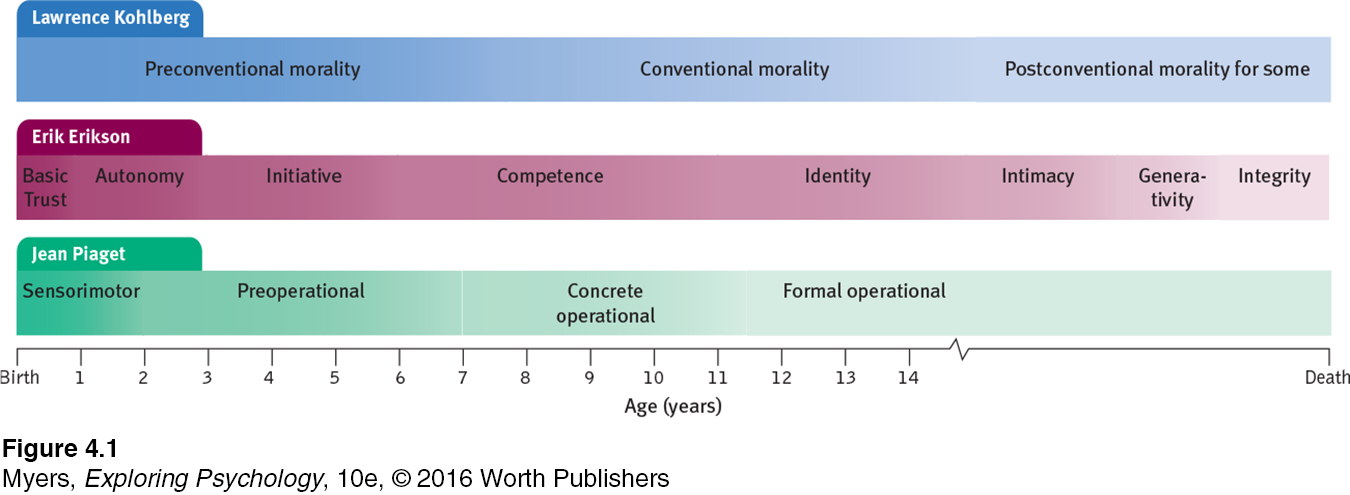

Researchers who emphasize experience and learning typically see development as a slow, continuous shaping process. Those who emphasize biological maturation tend to see development as a sequence of genetically predisposed stages or steps: Although progress through the various stages may be quick or slow, everyone passes through the stages in the same order.

Are there clear-

Although many modern developmental psychologists do not identify as stage theorists, the stage concept remains useful. The human brain does experience growth spurts during childhood and puberty that correspond roughly to Piaget’s stages (Thatcher et al., 1987). And stage theories contribute a developmental perspective on the whole life span, by suggesting how people of one age think and act differently when they arrive at a later age.

Stability and Change

As we follow lives through time, do we find more evidence for stability or change? If reunited with a long-

Research reveals that we experience both stability and change. Some of our characteristics, such as temperament, are very stable:

One research team that studied 1000 people from ages 3 to 38 was struck by the consistency of temperament and emotionality across time (Moffitt et al., 2013; Slutske et al., 2012). Out-

of- control 3- year- olds were the most likely to become teen smokers or adult criminals or out- of- control gamblers. Other studies have found that hyperactive, inattentive 5-

year- olds required more teacher effort at age 12 (Houts et al., 2010); that 6- year- old Canadian boys with conduct problems were four times more likely than other boys to be convicted of a violent crime by age 24 (Hodgins et al., 2013); and that extraversion among British 16- year- olds predicted their future happiness as 60- year- olds (Gale et al., 2013). Page 122Another research team interviewed adults who, 40 years earlier, had their talkativeness, impulsiveness, and humility rated by their elementary school teachers (Nave et al., 2010). To a striking extent, their traits persisted.

“At 70, I would say the advantage is that you take life more calmly. You know that ‘this, too, shall pass’!”

Eleanor Roosevelt, 1954

“As at 7, so at 70,” says a Jewish proverb. People predict that they will not change much in the future (Quoidbach et al., 2013). In some ways they are correct. The widest smilers in childhood and college photos are, years later, the ones most likely to enjoy enduring marriages (Hertenstein et al., 2009).

We cannot, however, predict all aspects of our future selves based on our early life. Our social attitudes, for example, are much less stable than our temperament (Moss & Susman, 1980). Older children and adolescents learn new ways of coping. Although delinquent children have elevated rates of later problems, many confused and troubled children blossom into mature, successful adults (Moffitt et al., 2002; Roberts et al., 2013; Thomas & Chess, 1986). The struggles of the present may be laying a foundation for a happier tomorrow. Life is a process of becoming.

In some ways, we all change with age. Most shy, fearful toddlers begin opening up by age 4, and most people become more conscientious, stable, agreeable, and self-

Life requires both stability and change. Stability provides our identity. It enables us to depend on others and be concerned about children’s healthy development. Our potential for change gives us our hope for a brighter future. It motivates our concerns about present influences and lets us adapt and grow with experience.

RETRIEVE IT

Question

Developmental researchers who consider how biological, psychological, and social-

Question

Developmental researchers who emphasize learning and experience are supporting ; those who emphasize biological maturation are supporting .

Question

What findings in psychology support (1) the stage theory of development and (2) the idea of stability in personality across the life span? What findings challenge these ideas?

Prenatal Development and the Newborn

4-

Conception

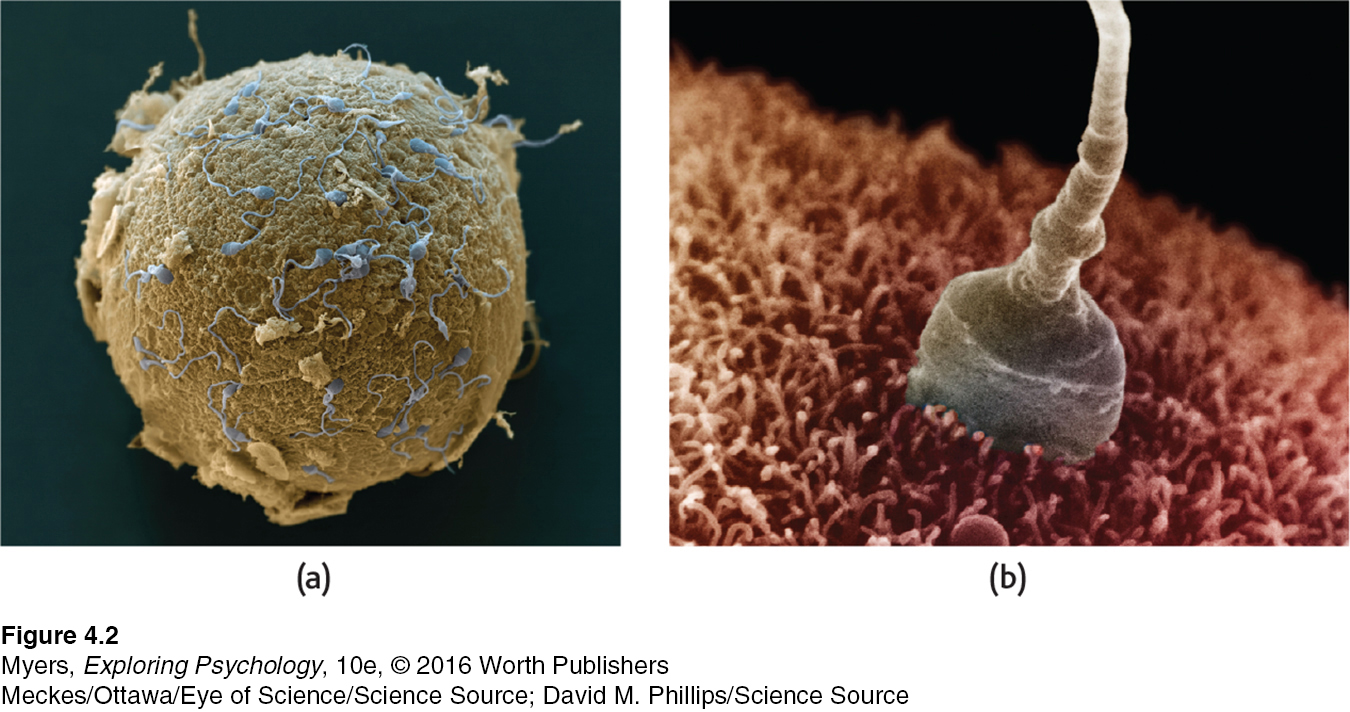

Nothing is more natural than a species reproducing itself. And nothing is more wondrous. For you, the process started inside your grandmother—

Some time after puberty, your mother’s ovary released a mature egg—

Consider it your most fortunate of moments. Among 250 million sperm, the one needed to make you, in combination with that one particular egg, won the race. And so it was for innumerable generations before us. If any one of our ancestors had been conceived with a different sperm or egg, or died before conceiving, or not chanced to meet their partner or. . . . The mind boggles at the improbable, unbroken chain of events that produced us.

Prenatal Development

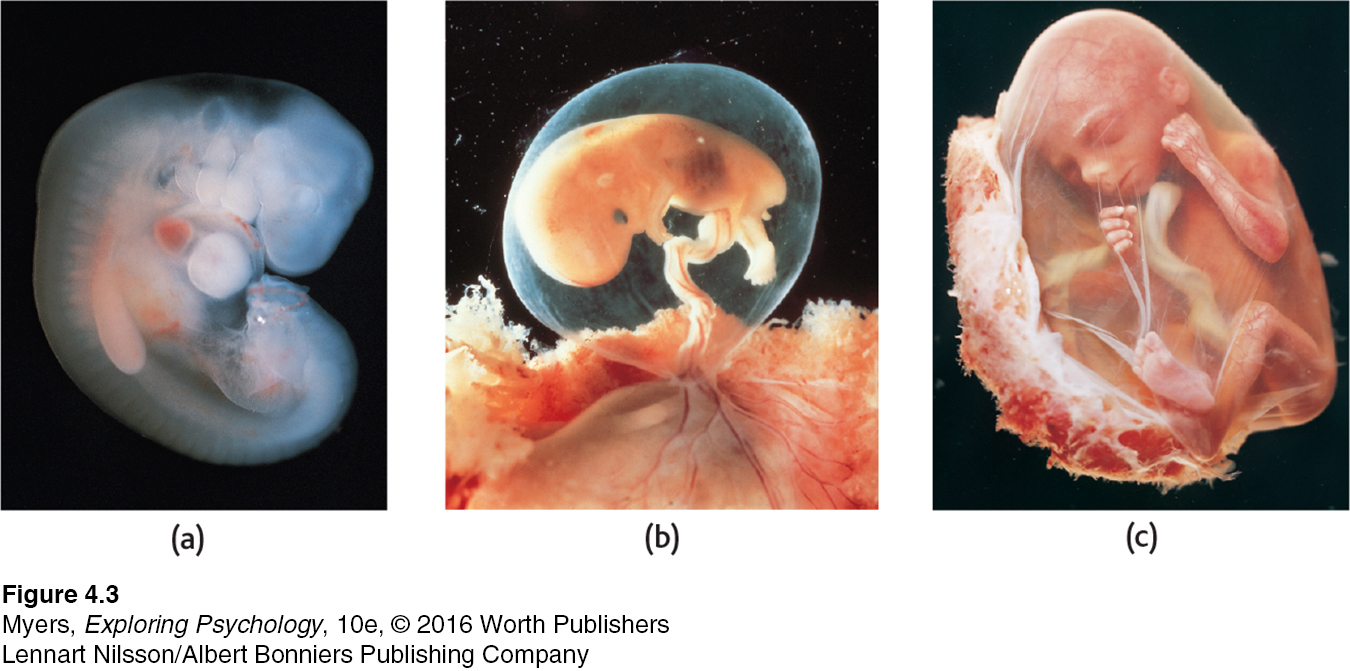

zygote the fertilized egg; it enters a 2-

How many fertilized eggs, called zygotes, survive beyond the first 2 weeks? Fewer than half (Grobstein, 1979; Hall, 2004). But for us, good fortune prevailed. One cell became 2, then 4—

Question

Care to guess your body's total number of cells?

embryo the developing human organism from about 2 weeks after fertilization through the second month.

About 10 days after conception, the zygote attaches to the mother’s uterine wall, beginning approximately 37 weeks of the closest human relationship. The zygote’s inner cells become the embryo (FIGURE 4.3a below). Many of its outer cells become the placenta, the life-

fetus the developing human organism from 9 weeks after conception to birth.

By 9 weeks after conception, an embryo looks unmistakably human (FIGURE 4.3b). It is now a fetus (Latin for “offspring” or “young one”). During the sixth month, organs such as the stomach have developed enough to give the fetus a good chance of survival if born prematurely.

At each prenatal stage, genetic and environmental factors affect our development. By the sixth month, microphone readings taken inside the uterus reveal that the fetus is responsive to sound and is exposed to the sound of its mother’s muffled voice (Ecklund-

They also prefer hearing their mother’s language. At about 30 hours old, American and Swedish newborns pause more in their pacifier sucking when listening to familiar vowels from their mother’s language (Moon et al., 2013). After repeatedly hearing a fake word (tatata) in the womb, Finnish newborns’ brain waves display recognition when hearing the word after birth (Partanen et al., 2014). If their mother spoke two languages during pregnancy, they display interest in both (Byers-

Prenatal development

Zygote: Conception to 2 weeks

Embryo: 2 to 9 weeks

Fetus: 9 weeks to birth

In the two months before birth, fetuses demonstrate learning in other ways, as when they adapt to a vibrating, honking device placed on their mother’s abdomen (Dirix et al., 2009). Like people who adapt to the sound of trains in their neighborhood, fetuses get used to the honking. Moreover, four weeks later, they recall the sound (as evidenced by their blasé response, compared with the reactions of those not previously exposed).

“You shall conceive and bear a son. So then drink no wine or strong drink.”

Judges 13:7

teratogens (literally, “monster maker”) agents, such as chemicals and viruses, that can reach the embryo or fetus during prenatal development and cause harm.

Sounds are not the only stimuli fetuses are exposed to in the womb. In addition to transferring nutrients and oxygen from mother to fetus, the placenta screens out many harmful substances. But some slip by. Teratogens, agents such as viruses and drugs, can damage an embryo or fetus. This is one reason pregnant women are advised not to drink alcoholic beverages or smoke cigarettes. A pregnant woman never drinks or smokes alone. When alcohol enters her bloodstream and that of her fetus, it reduces activity in both their central nervous systems. Alcohol use during pregnancy may prime the woman’s offspring to like alcohol and may put them at risk for heavy drinking and alcohol use disorder during their teen years. In experiments, when pregnant rats drank alcohol, their young offspring later displayed a liking for alcohol’s taste and odor (Youngentob et al., 2007, 2009).

fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) physical and cognitive abnormalities in children caused by a pregnant woman’s heavy drinking. In severe cases, signs include a small, out-

For an interactive review of prenatal development, see LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Conception to Birth. See also LaunchPad's 8-

For an interactive review of prenatal development, see LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Conception to Birth. See also LaunchPad's 8-

Even light drinking or occasional binge drinking can affect the fetal brain (Braun, 1996; Ikonomidou et al., 2000; Marjonen et al., 2015; Sayal et al., 2009). Persistent heavy drinking puts the fetus at risk for a dangerously low birth weight, birth defects, and for future behavior problems, hyperactivity, and lower intelligence. For 1 in about 700 children, the effects are visible as fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), marked by lifelong physical and mental abnormalities (May et al., 2014). The fetal damage may occur because alcohol has an epigenetic effect: It leaves chemical marks on DNA that switch genes abnormally on or off (Liu et al., 2009). Smoking during pregnancy also leaves epigenetic scars that weaken infants’ ability to handle stress (Stroud et al., 2014).

If a pregnant woman experiences extreme stress, the stress hormones flooding her body may indicate a survival threat to the fetus and produce an earlier delivery (Glynn & Sandman, 2011). Some stress in early life prepares us to cope with later adversity in life. But substantial prenatal stress exposure puts a child at increased risk for health problems such as hypertension, heart disease, obesity, and psychiatric disorders.

RETRIEVE IT

Question

The first two weeks of prenatal development is the period of the . The period of the lasts from 9 weeks after conception until birth. The time between those two prenatal periods is considered the period of the .

The Competent Newborn

4-3 What are some newborn abilities, and how do researchers explore infants’ mental abilities?

“I felt like a man trapped in a woman’s body. Then I was born.”

Comedian Chris Bliss

Babies come with software preloaded on their neural hard drives. Having survived prenatal hazards, we as newborns came equipped with automatic reflex responses ideally suited for our survival. We withdrew our limbs to escape pain. If a cloth over our face interfered with our breathing, we turned our head from side to side and swiped at it.

New parents are often in awe of the coordinated sequence of reflexes by which their baby gets food. When something touches their cheek, babies turn toward that touch, open their mouth, and vigorously root for a nipple. Finding one, they automatically close on it and begin sucking—

The pioneering American psychologist William James presumed that newborns experience a “blooming, buzzing confusion,” an assumption few people challenged until the 1960s. Then scientists discovered that babies can tell you a lot—

habituation decreasing responsiveness with repeated stimulation. As infants gain familiarity with repeated exposure to a stimulus, their interest wanes and they look away sooner.

Consider how researchers exploit habituation—decreased responding with repeated stimulation. We saw this earlier when fetuses adapted to a vibrating, honking device placed on their mother’s abdomen. The novel stimulus gets attention when first presented. With repetition, the response weakens. This seeming boredom with familiar stimuli gives us a way to ask infants what they see and remember.

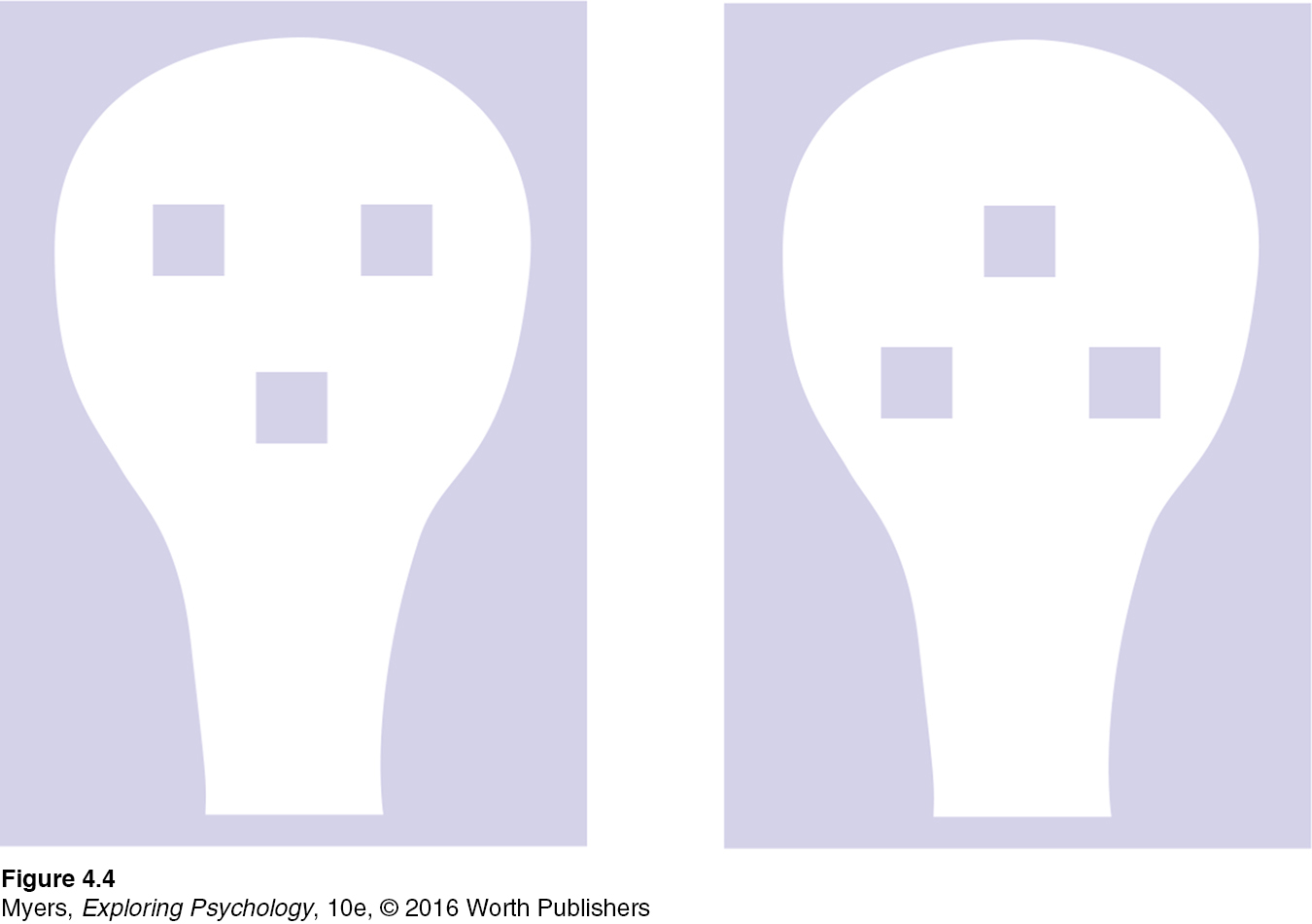

Even as newborns, we prefer sights and sounds that facilitate social responsiveness. We turn our heads in the direction of human voices. We gaze longer at a drawing of a face-

Within days after birth, our brain’s neural networks were stamped with the smell of our mother’s body. Week-

RETRIEVE IT

Question

Developmental psychologists use repeated stimulation to test an infant's to a stimulus.

REVIEW Developmental Issues, Prenatal Development, and the Newborn

Learning Objectives

Test Yourself by taking a moment to answer each of these Learning Objective Questions (repeated here from within the chapter). Research suggests that trying to answer these questions on your own will improve your long-

Question

4-

Question

4-

Question

4-

Terms and Concepts to Remember

Test yourself on these terms.

Question

developmental psychology (p. 120) zygote (p. 123) embryo (p. 123) fetus (p. 123) teratogens (p. 124) fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) (p. 124) habituation (p. 125) | physical and cognitive abnormalities in children caused by a pregnant woman's heavy drinking. In severe cases, signs include a small, out- a branch of psychology that studies physical, cognitive, and social change throughout the life span. the developing human organism from 9 weeks after conception to birth. the fertilized egg; it enters a 2- (literally, “monster maker') agents, such as chemicals and viruses, that can reach the embryo or fetus during prenatal development and cause harm. decreasing responsiveness with repeated stimulation. As infants gain familiarity with repeated exposure to a stimulus, their interest wanes and they look away sooner. the developing human organism from about 2 weeks after fertilization through the second month. |

Experience the Testing Effect

Test yourself repeatedly throughout your studies. This will not only help you figure out what you know and don’t know; the testing itself will help you learn and remember the information more effectively thanks to the testing effect.

Question 4.1

1. The three major issues that interest developmental psychologists are nature/nurture, stability/change, and / .

Question 4.2

2. Although development is lifelong, there is stability of personality over time. For example,

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 4.3

3. From the very first weeks of life, infants differ in their characteristic emotional reactions, with some infants being intense and anxious, while others are easygoing and relaxed. These differences are usually explained as differences in .

Question 4.4

4. Body organs first begin to form and function during the period of the ________; within 6 months, during the period of the ________, the organs are sufficiently functional to allow a good chance of survival.

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 4.5

5. Chemicals that pass through the placenta's screen and may harm an embryo or fetus are called .

Use  to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in

to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in  .

.