4.2 Infancy and Childhood

maturation biological growth processes that enable orderly changes in behavior, relatively uninfluenced by experience.

As a flower unfolds in accord with its genetic instructions, so do we. Maturation—

“It is a rare privilege to watch the birth, growth, and first feeble struggles of a living human mind.”

Annie Sullivan, in Helen Keller’s

The Story of My Life, 1903

Physical Development

4-

Brain Development

Our formative nurture began at conception, with the prenatal environment in the womb. Nurture continued outside the womb, where our early experiences fostered brain development.

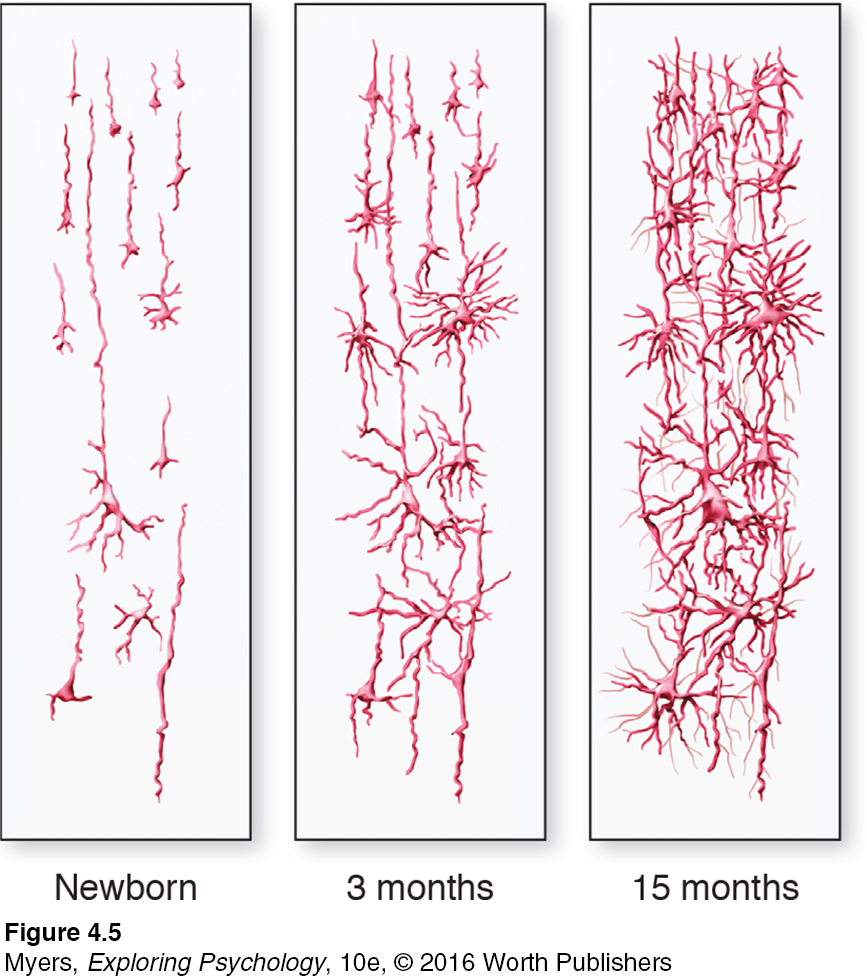

In your mother’s womb, your developing brain formed nerve cells at the explosive rate of nearly one-

From ages 3 to 6, the most rapid brain growth was in your frontal lobes, which enable rational planning. During those years, your brain required vast amounts of energy (Kuzawa et al., 2014). This energy-

The last cortical areas to develop are the association areas—

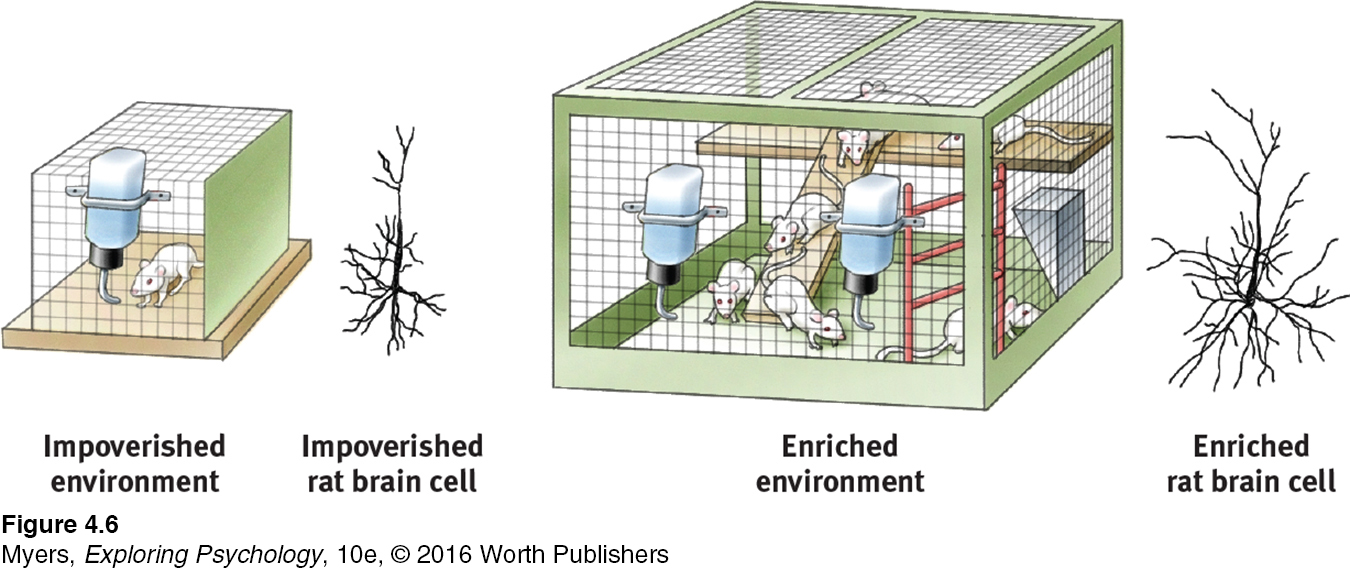

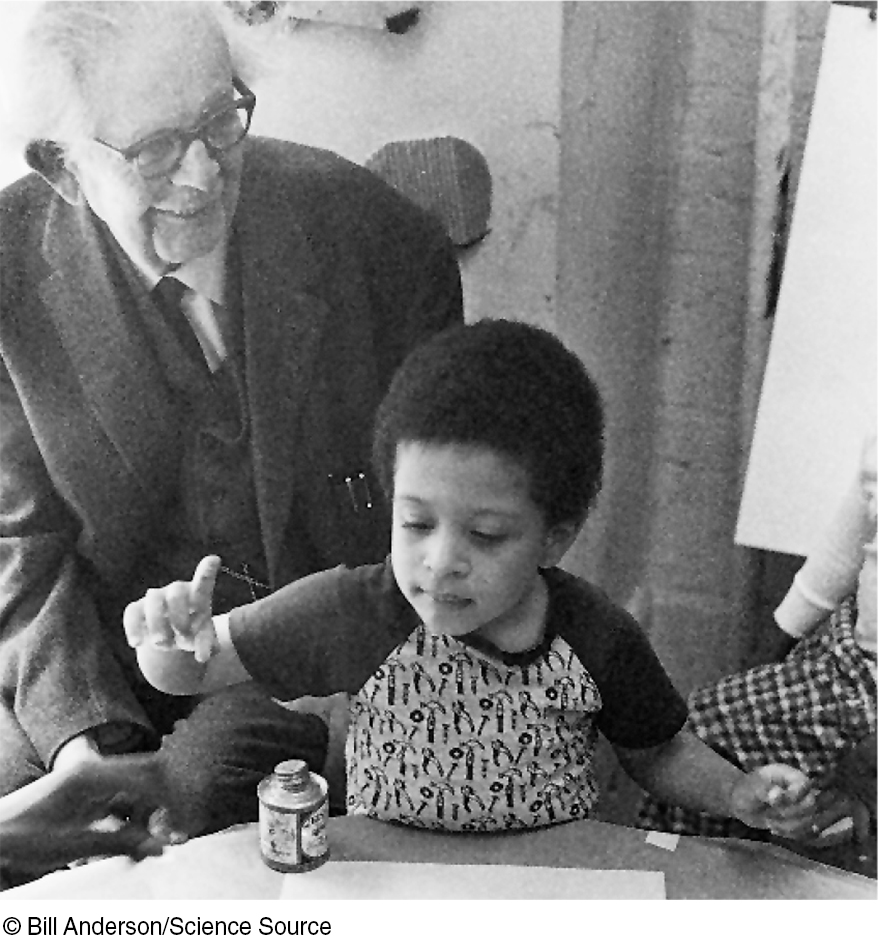

Your genes dictate your overall brain architecture, rather like the lines of a coloring book, but experience fills in the details (Kenrick et al., 2009). So how do early experiences leave their “fingerprints” in the brain? Mark Rosenzweig, David Krech, and their colleagues (1962) opened a window on that process when they raised some young rats in solitary confinement, and others in a communal playground that simulated a natural environment. When the researchers later analyzed the rats’ brains, those living in the enriched environment had usually developed a heavier and thicker brain cortex (FIGURE 4.6 below). So great are the effects that, shown brief video clips, you could tell from the rats’ activity and curiosity whether their environment had been impoverished or enriched (Renner & Renner, 1993). After 60 days in the enriched environment, the rats’ brain weights increased 7 to 10 percent and the number of synapses mushroomed by about 20 percent (Kolb & Whishaw, 1998).

Such results have motivated improvements in environments for laboratory, farm, and zoo animals—

Nature and nurture interact to sculpt our synapses. Brain maturation provides us with an abundance of neural connections. Experiences—

critical period an optimal period early in the life of an organism when exposure to certain stimuli or experiences produces normal development.

Here at the juncture of nurture and nature is the biological reality of early childhood learning. During early childhood—

“Genes and experiences are just two ways of doing the same thing—

Joseph LeDoux,

The Synaptic Self, 2002

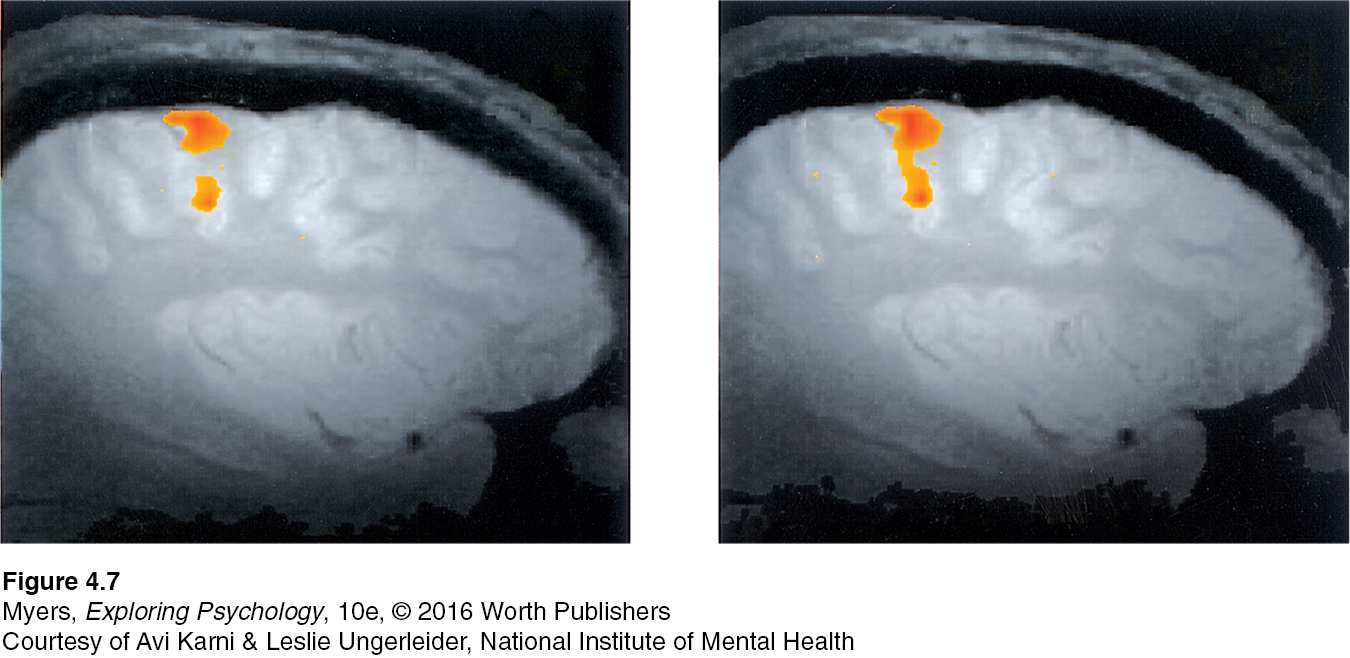

Although normal stimulation during the early years is critical, the brain’s development does not end with childhood. Thanks to the brain’s amazing plasticity, our neural tissue is ever changing and reorganizing in response to new experiences. New neurons also are born. If a monkey pushes a lever with the same finger many times a day, brain tissue controlling that finger changes to reflect the experience (FIGURE 4.7). Human brains work similarly. Whether learning to keyboard, skateboard, or navigate London’s streets, we perform with increasing skill as our brain incorporates the learning (Ambrose, 2010; Maguire et al., 2000).

Motor Development

The developing brain enables physical coordination. As an infant exercises its maturing muscles and nervous system, skills emerge. With occasional exceptions, the sequence of physical (motor) development is universal. Babies roll over before they sit unsupported, and they usually crawl on all fours before they walk. These behaviors reflect not imitation but a maturing nervous system; blind children, too, crawl before they walk.

In the United States, 25 percent of all babies walk by 11 months of age, 50 percent within a week after their first birthday, and 90 percent by age 15 months (Frankenburg et al., 1992). In some regions of Africa, the Caribbean, and India, caregivers frequently massage and exercise babies, which can accelerate the process of learning to walk (Karasik et al., 2010). The recommended infant back to sleep position (putting babies to sleep on their backs to reduce the risk of a smothering crib death) has been associated with somewhat later crawling but not with later walking (Davis et al., 1998; Lipsitt, 2003).

In the eight years following the 1994 launch of a U.S. Back to Sleep educational campaign, the number of infants sleeping on their stomach dropped from 70 to 11 percent—

Genes guide motor development. Identical twins typically begin walking on nearly the same day (Wilson, 1979). Maturation—

RETRIEVE IT

Question

The biological growth process, called , explains why most children begin walking by about 12 to 15 months.

Brain Maturation and Infant Memory

Can you recall your first day of preschool or your third birthday party? Studies have confirmed that our average age of earliest conscious memory is 3.5 years (Bauer, 2002, 2007). But as children mature, by age 7 or so, infantile amnesia wanes, and they become increasingly capable of remembering experiences, even for a year or more (Bauer & Larkina, 2014; Morris et al., 2010). Mice and monkeys also forget their early life, as rapid neuron growth disrupts the circuits that stored old memories (Akers et al., 2014). The brain areas underlying memory, such as the hippocampus and frontal lobes, continue to mature into adolescence (Bauer, 2007).

Apart from constructed memories based on photos and family stories, we consciously recall little from our early years, yet our brain was processing and storing information. While finishing her doctoral work in psychology, Carolyn Rovee-

Traces of forgotten childhood languages may also persist. One study tested English-

Cognitive Development

4-

cognition all the mental activities associated with thinking, knowing, remembering, and communicating.

Somewhere on your life journey, you became conscious. When was that? Jean Piaget [pee-

A half-

Piaget’s studies led him to believe that a child’s mind develops through a series of stages, in an upward march from the newborn’s simple reflexes to the adult’s abstract reasoning power. Thus, an 8-

schema a concept or framework that organizes and interprets information.

Piaget’s core idea was that our intellectual progression reflects an unceasing struggle to make sense of our experiences. To this end, the maturing brain builds schemas, concepts or mental molds into which we pour our experiences. By adulthood we have built countless schemas, ranging from cats and dogs to our concept of love.

assimilation interpreting our new experiences in terms of our existing schemas.

accommodation adapting our current understandings (schemas) to incorporate new information.

To explain how we use and adjust our schemas, Piaget proposed two more concepts. First, we assimilate new experiences—

Piaget’s Theory and Current Thinking

Piaget believed that children construct their understanding of the world while interacting with it. Their minds experience spurts of change, followed by greater stability as they move from one cognitive plateau to the next, each with distinctive characteristics that permit specific kinds of thinking. In Piaget’s view, cognitive development consisted of four major stages—

sensorimotor stage in Piaget’s theory, the stage (from birth to nearly 2 years of age) during which infants know the world mostly in terms of their sensory impressions and motor activities.

SENSORIMOTOR STAGE In the sensorimotor stage, from birth to nearly age 2, babies take in the world through their senses and actions—

object permanence the awareness that things continue to exist even when not perceived.

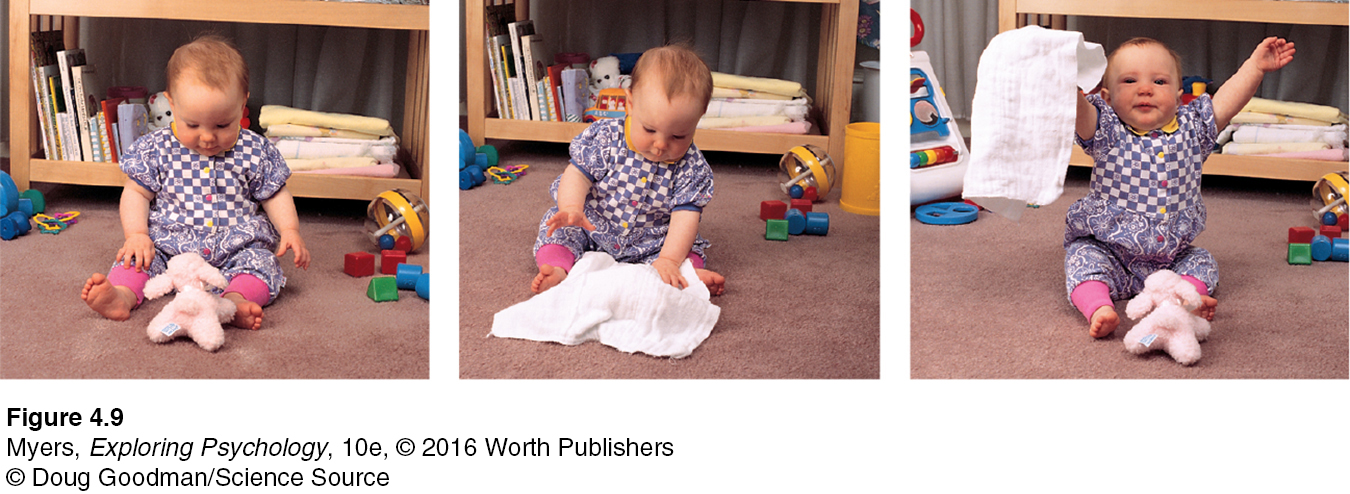

Very young babies seem to live in the present: Out of sight is out of mind. In one test, Piaget showed an infant an appealing toy and then flopped his beret over it. Before the age of 6 months, the infant acted as if the toy ceased to exist. Young infants lack object permanence—the awareness that objects continue to exist when not perceived. By 8 months, infants begin exhibiting memory for things no longer seen. If you hide a toy, the infant will momentarily look for it (FIGURE 4.9). Within another month or two, the infant will look for it even after being restrained for several seconds.

So does object permanence in fact blossom suddenly at 8 months, much as tulips blossom in spring? Today’s researchers believe object permanence unfolds gradually, and they see development as more continuous than Piaget did. Even young infants will at least momentarily look for a toy where they saw it hidden a second before (Wang et al., 2004).

Researchers also believe Piaget and his followers underestimated young children’s competence. Preschoolers think like little scientists. They test ideas, make causal inferences, and learn from statistical patterns (Gopnik et al., 2015). Consider these simple experiments:

Baby physics: Like adults staring in disbelief at a magic trick (the “Whoa!” look), infants look longer at and explore an unexpected, impossible, or unfamiliar scene—

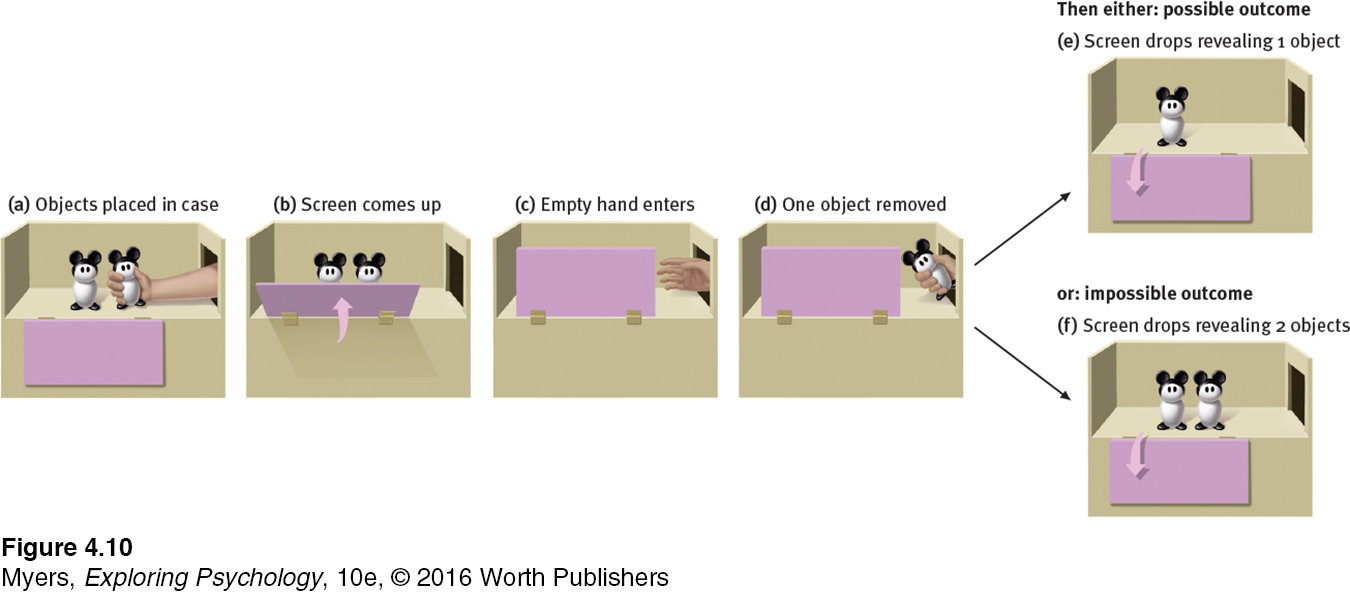

a car seeming to pass through a solid object, a ball stopping in midair, or an object violating object permanence by magically disappearing (Baillargeon, 1995, 2008; Shuwairi & Johnson, 2013; Stahl & Feigenson, 2015). Baby math: Karen Wynn (1992, 2000, 2008) showed 5-

month- olds one or two objects (FIGURE 4.10a). Then she hid the objects behind a screen, and visibly removed or added one (FIGURE 4.10d). When she lifted the screen, the infants sometimes did a double take, staring longer when shown a wrong number of objects (FIGURE 4.10f). But were they just responding to a greater or smaller mass of objects, rather than a change in number (Feigenson et al., 2002)? Later experiments showed that babies’ number sense extends to larger numbers, to ratios, and to such things as drumbeats and motions (Libertus & Brannon, 2009; McCrink & Wynn, 2004; Spelke et al., 2013). If accustomed to a Daffy Duck puppet jumping three times on stage, they showed surprise if it jumped only twice.

Clearly, infants are smarter than Piaget appreciated. Even as babies, we had a lot on our minds.

preoperational stage in Piaget’s theory, the stage (from about 2 to about 6 or 7 years of age) during which a child learns to use language but does not yet comprehend the mental operations of concrete logic.

conservation the principle (which Piaget believed to be a part of concrete operational reasoning) that properties such as mass, volume, and number remain the same despite changes in the forms of objects.

PREOPERATIONAL STAGE Piaget believed that until about age 6 or 7, children are in a preoperational stage—able to represent things with words and images but too young to perform mental operations (such as imagining an action and mentally reversing it). For a 5-

For quick video examples of children being tested for conservation, visit LaunchPad’s Concept Practice: Piaget and Conservation.

For quick video examples of children being tested for conservation, visit LaunchPad’s Concept Practice: Piaget and Conservation.

PRETEND PLAY A child who can perform mental operations can think in symbols and enjoy pretend play. Researchers have found that symbolic thinking appears at an earlier age than Piaget supposed. Judy DeLoache (1987) showed children a model of a room and hid a miniature stuffed dog behind its miniature couch. The 2½-year-

egocentrism in Piaget’s theory, the preoperational child’s difficulty taking another’s point of view.

EGOCENTRISM Piaget contended that preschool children are egocentric: They have difficulty perceiving things from another’s point of view. They are like the person who, when asked by someone across a river, “How do I get to the other side?” answered “You are on the other side.” Asked to “show Mommy your picture,” 2-

“Do you have a brother?”

“Yes.”

“What’s his name?”

“Jim.”

“Does Jim have a brother?”

“No.”

Like Gabriella, TV-

“The curse of knowledge is the single best explanation I know of why good people write bad prose. It simply doesn’t occur to the writer that her readers don’t know what she knows.”

Psychologist Steven Pinker,

The Sense of Style, 2014

theory of mind people’s ideas about their own and others’ mental states—

THEORY OF MIND When Little Red Riding Hood realized her “grandmother” was really a wolf, she swiftly revised her ideas about the creature’s intentions and raced away. Preschoolers, although still egocentric, develop this ability to infer others’ mental states when they begin forming a theory of mind (Premack & Woodruff, 1978). The theory of mind concept was first used to describe chimpanzees’ seeming ability to read others’ intentions. Later, psychologists aimed to identify when humans develop a theory of mind.

As the ability to take another’s perspective gradually develops, preschoolers come to understand what made a playmate angry, when a sibling will share, and what might make a parent buy a toy. And they begin to tease, empathize, and persuade. Being able to take another’s perspective enables relationships. Children who have an advanced ability to understand others’ minds tend to be more popular (Slaughter et al., 2015).

Between about ages 3 and 4½, children worldwide come to realize that others may hold false beliefs (Callaghan et al., 2005; Rubio-

concrete operational stage in Piaget’s theory, the stage of cognitive development (from about 7 to 11 years of age) during which children gain the mental operations that enable them to think logically about concrete events.

CONCRETE OPERATIONAL STAGE By about age 7, said Piaget, children enter the concrete operational stage. Given concrete (physical) materials, they begin to grasp conservation. Understanding that change in form does not mean change in quantity, they can mentally pour milk back and forth between glasses of different shapes. They also enjoy jokes that use this new understanding:

Mr. Jones went into a restaurant and ordered a whole pizza for his dinner. When the waiter asked if he wanted it cut into 6 or 8 pieces, Mr. Jones said, “Oh, you’d better make it 6, I could never eat 8 pieces!” (McGhee, 1976)

Piaget believed that during the concrete operational stage, children become able to comprehend mathematical transformations and conservation. When my [DM’s] daughter, Laura, was 6, I was astonished at her inability to reverse simple arithmetic. Asked, “What is 8 plus 4?” she required 5 seconds to compute “12,” and another 5 seconds to then compute 12 minus 4. By age 8, she could answer a reversed question instantly.

formal operational stage in Piaget’s theory, the stage of cognitive development (normally beginning about age 12) during which people begin to think logically about abstract concepts.

FORMAL OPERATIONAL STAGE By about age 12, our reasoning expands from the purely concrete (involving actual experience) to encompass abstract thinking (involving imagined realities and symbols). As children approach adolescence, said Piaget, they can ponder hypothetical propositions and deduce consequences: If this, then that. Systematic reasoning, what Piaget called formal operational thinking, is now within their grasp.

Although full-

If John is in school, then Mary is in school. John is in school. What can you say about Mary?

Formal operational thinkers have no trouble answering correctly. But neither do most 7-

Piaget’s Stages of Cognitive Development

| Typical Age Range | Description of Stage | Developmental Phenomena |

|---|---|---|

| Birth to nearly 2 years |

Sensorimotor Experiencing the world through senses and actions (looking, hearing, touching, mouthing, and grasping) |

|

| About 2 to about 6 or 7 years |

Preoperational Representing things with words and images; using intuitive rather than logical reasoning |

|

| About 7 to 11 years |

Concrete operational Thinking logically about concrete events; grasping concrete analogies and performing arithmetical operations |

|

| About 12 through adulthood |

Formal operational Abstract reasoning |

|

An Alternative Viewpoint: Lev Vygotsky and the Social Child

As Piaget was forming his theory of cognitive development, Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky was also studying how children think and learn. He noted that by age 7, they increasingly think in words and use words to solve problems. They do this, he said, by internalizing their culture’s language and relying on inner speech (Fernyhough, 2008). Parents who say “No, no!” when pulling a child’s hand away from a cake are giving the child a self-

Where Piaget emphasized how the child’s mind grows through interaction with the physical environment, Vygotsky emphasized how the child’s mind grows through interaction with the social environment. If Piaget’s child was a young scientist, Vygotsky’s was a young apprentice. By mentoring children and giving them new words, parents and others provide a temporary scaffold from which children can step to higher levels of thinking (Renninger & Granott, 2005). Language, an important ingredient of social mentoring, provides the building blocks for thinking, noted Vygotsky (who was born the same year as Piaget, but died prematurely of tuberculosis).

RETRIEVE IT

Question

Object permanence, pretend play, conservation, and abstract logic are developmental milestones for which of Piaget's stages, respectively?

Match the correct cognitive developmental stage to each developmental phenomenon.

Question

Thinking about abstract concepts, such as “freedom.” Enjoying imaginary play (such as dress- Understanding that physical properties stay the same even when objects change form. | Preoperational Concrete operational Formal operational |

Question

Having the ability to reverse math operations. Understanding that something is not gone for good when it disappears from sight, as when Mom “disappears” behind the shower curtain. Having difficulty taking another's point of view (as when blocking someone's view of the TV). | Sensorimotor Preoperational Concrete operational |

Reflecting on Piaget’s Theory

“Assessing the impact of Piaget on developmental psychology is like assessing the impact of Shakespeare on English literature.”

Developmental psychologist

Harry Beilin (1992)

What remains of Piaget’s ideas about the child’s mind? Plenty—

However, today’s researchers see development as more continuous than did Piaget. By detecting the beginnings of each type of thinking at earlier ages, they have revealed conceptual abilities Piaget missed. Moreover, they see formal logic as a smaller part of cognition than he did. Piaget would not be surprised that today, as part of our own cognitive development, we are adapting his ideas to accommodate new findings.

“Childhood has its own way of seeing, thinking, and feeling, and there is nothing more foolish than the attempt to put ours in its place.”

Philosopher Jean-

IMPLICATIONS FOR PARENTS AND TEACHERS Future parents and teachers, remember this: Young children are incapable of adult logic. Preschoolers who block one’s view of the TV simply have not learned to take another’s viewpoint. What seems simple and obvious to us—

For a 7-

For a 7-

Autism Spectrum Disorder

4-

autism spectrum disorder (ASD) a disorder that appears in childhood and is marked by significant deficiencies in communication and social interaction, and by rigidly fixated interests and repetitive behaviors.

Diagnoses of autism spectrum disorder (ASD), a disorder marked by social deficiencies and repetitive behaviors, have been increasing. Once believed to affect 1 in 2500 children (and referred to simply as autism), ASD now gets diagnosed in 1 in 68 American children by age 8. But the reported rates vary by place, with New Jersey having four times the reported prevalence of Alabama, while Britain’s children have a 1 in 100 rate, and South Korea’s 1 in 38 (CDC, 2014; Kim et al., 2011; NAS, 2011). The increase in ASD diagnoses has been offset by a decrease in the number of children with a “cognitive disability” or “learning disability,” which suggests a relabeling of children’s disorders (Gernsbacher et al., 2005; Grinker, 2007; Shattuck, 2006).

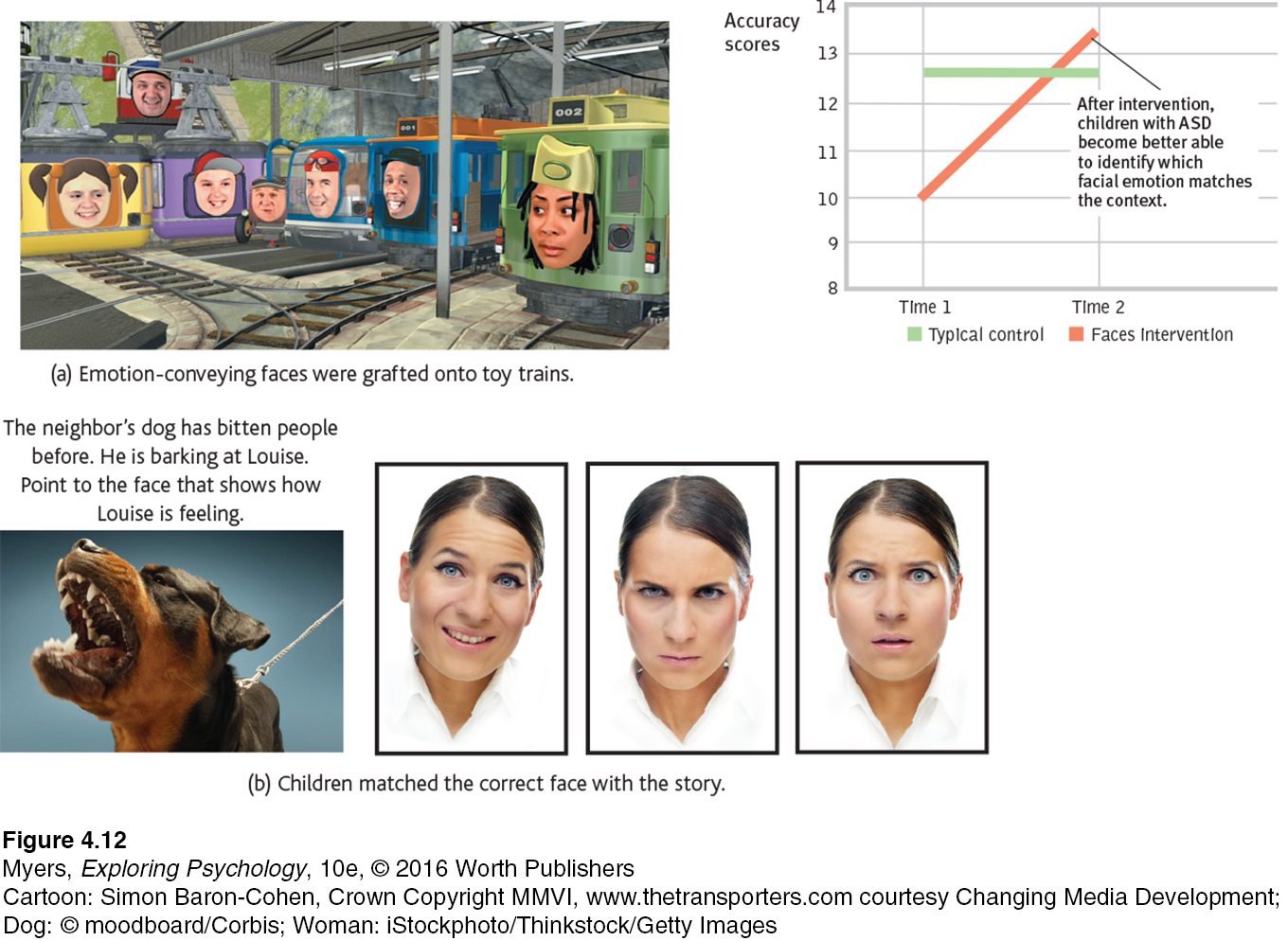

The underlying source of ASD’s symptoms seems to be poor communication among brain regions that normally work together to let us take another’s viewpoint. From age 2 months on, as other children spend more and more time looking into others’ eyes, those who later develop ASD do so less and less (Jones & Klin, 2013). People with ASD are said to have an impaired theory of mind (Rajendran & Mitchell, 2007; Senju et al., 2009). Mind reading that most of us find intuitive (Is that face conveying a smirk or a sneer?) is difficult for those with ASD. They have difficulty inferring and remembering others’ thoughts and feelings, learning that twinkling eyes mean happiness or mischief, and appreciating that playmates and parents might view things differently (Boucher et al., 2012; Frith & Frith, 2001). Partly for such reasons, a national survey of parents and school staff reported that 46 percent of adolescents with ASD had suffered the taunts and torments of bullying—

ASD has differing levels of severity. Some (those diagnosed with what used to be called Asperger syndrome) generally function at a high level. They have normal intelligence, often accompanied by exceptional skill or talent in a specific area, but deficient social and communication skills and a tendency to become distracted by irrelevant stimuli (Remington et al., 2009). Those at the spectrum’s lower end struggle to use language at all.

Biological factors, including genetic influences and abnormal brain development, contribute to ASD (State & Šestan, 2012). Studies suggest that the prenatal environment matters, especially when altered by maternal infection and inflammation, psychiatric drug use, or stress hormones (NIH, 2013; Wang, 2014). Childhood MMR vaccinations do not contribute to ASD (Demicheli et al., 2012; DeStefano et al., 2013). Based on a fraudulent 1998 study—

Both boys and girls can have ASD, but there are large gender differences. ASD afflicts about four boys for every girl. Children for whom amniotic fluid analyses indicated high prenatal testosterone develop more masculine and ASD-

Numerous studies verify biology’s influence. If one identical twin is diagnosed with ASD, the chances are 50 to 70 percent that the co-

Researchers are also sleuthing ASD’s telltale signs in the brain’s structure. Several studies have revealed underconnectivity—

Biology’s role in ASD also appears in the brain’s functioning. People without ASD often yawn after seeing others yawn. And as they view and imitate another’s smiling or frowning, they feel something of what the other is feeling. Not so among those with ASD, who are less imitative and show much less activity in brain areas involved in mirroring others’ actions (Dapretto et al., 2006; Perra et al., 2008; Senju et al., 2007). When people with ASD watch another person’s hand movements, for example, their brain displays less-

Seeking to “systemize empathy,” Baron-

RETRIEVE IT

Question

What does theory of mind have to do with autism spectrum disorder?

Social Development

4-

stranger anxiety the fear of strangers that infants commonly display, beginning by about 8 months of age.

From birth, babies are normally very social creatures, developing an intense bond with their caregivers. Infants come to prefer familiar faces and voices, then to coo and gurgle when given a parent’s attention. After about 8 months, soon after object permanence emerges and children become mobile, a curious thing happens: They develop stranger anxiety. They may greet strangers by crying and reaching for familiar caregivers. “No! Don’t leave me!” their distress seems to say. Children this age have schemas for familiar faces; when they cannot assimilate the new face into these remembered schemas, they become distressed (Kagan, 1984). Once again, we see an important principle: The brain, mind, and social-

Human Bonding

attachment an emotional tie with another person; shown in young children by their seeking closeness to the caregiver and showing distress on separation.

One-

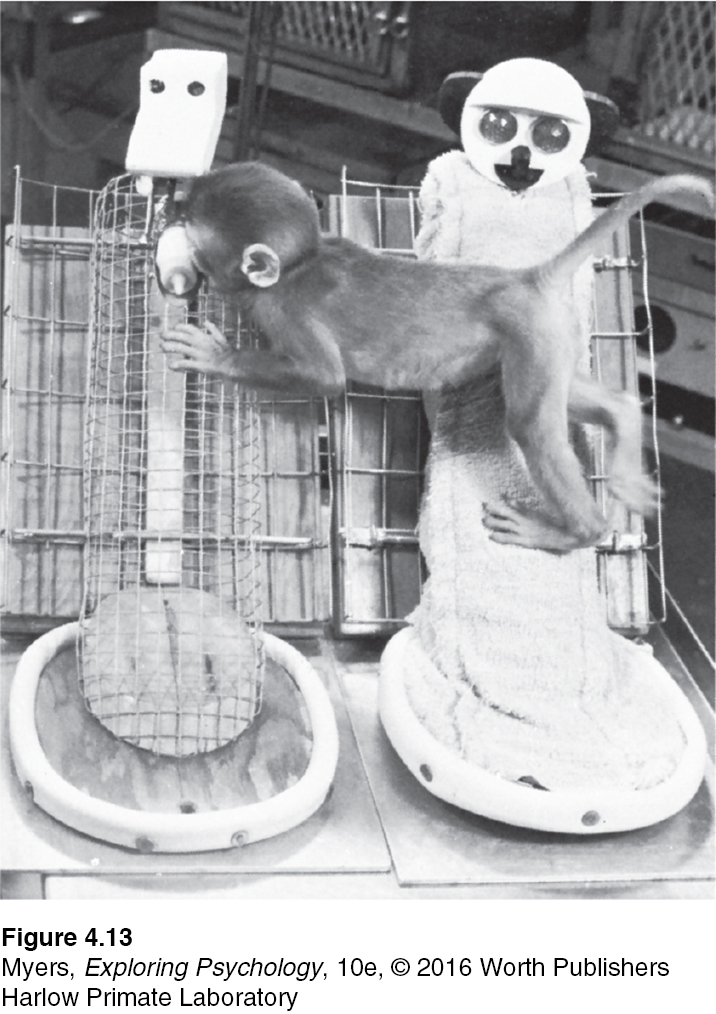

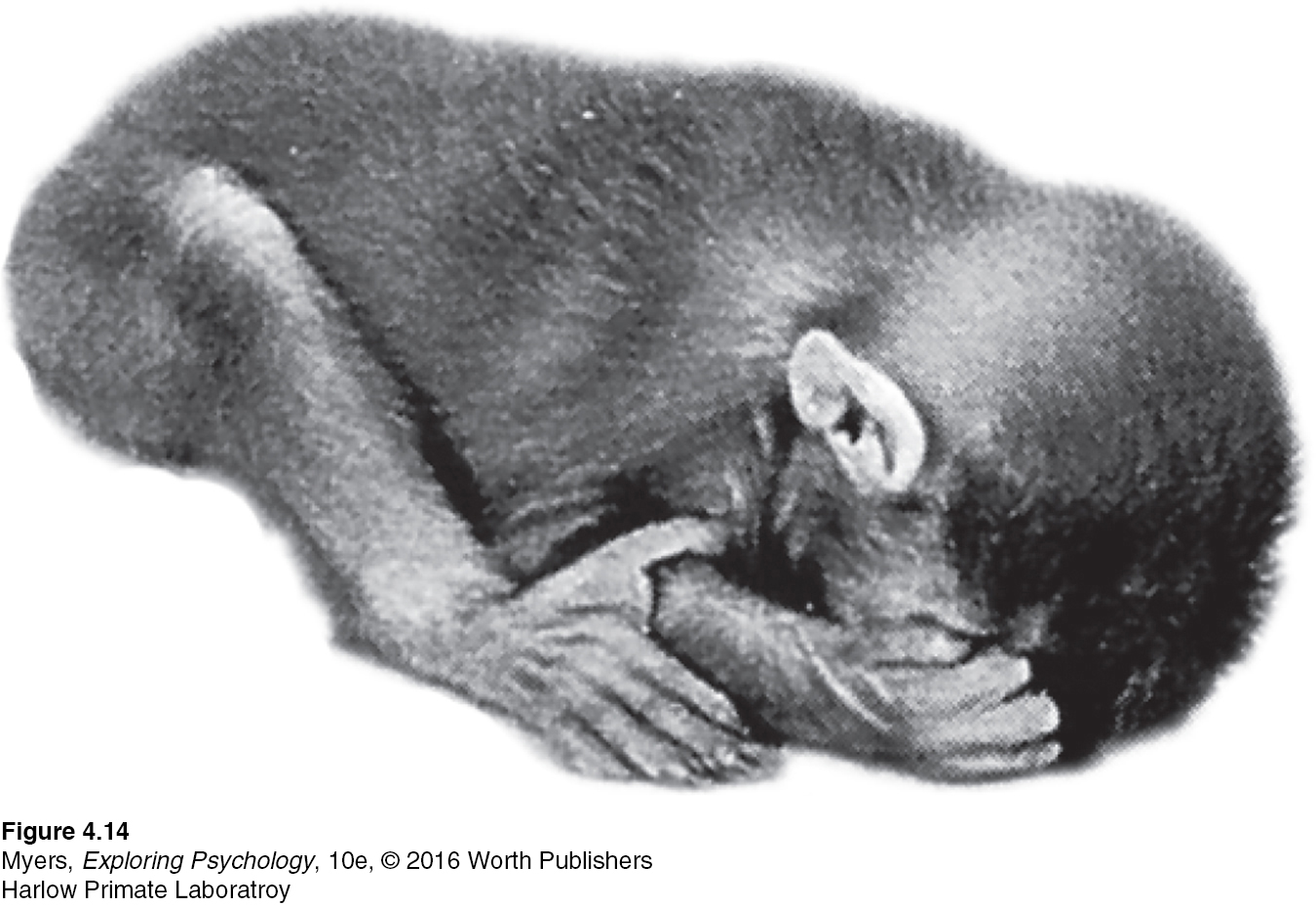

BODY CONTACT During the 1950s, University of Wisconsin psychologists Harry Harlow and Margaret Harlow bred monkeys for their learning studies. To equalize experiences and to isolate any disease, they separated the infant monkeys from their mothers shortly after birth and raised them in sanitary individual cages, which included a cheesecloth baby blanket (Harlow et al., 1971). Then came a surprise: When their soft blankets were taken to be laundered, the monkeys became distressed.

The Harlows recognized that this intense attachment to the blanket contradicted the idea that attachment derives from an association with nourishment. But how could they show this more convincingly? To pit the drawing power of a food source against the contact comfort of the blanket, they created two artificial mothers. One was a bare wire cylinder with a wooden head and an attached feeding bottle, the other a cylinder wrapped with terry cloth.

When raised with both, the monkeys overwhelmingly preferred the comfy cloth mother (FIGURE 4.13). Like other infants clinging to their live mothers, the monkey babies would cling to their cloth mothers when anxious. When exploring their environment, they used her as a secure base, as if attached to her by an invisible elastic band that stretched only so far before pulling them back. Researchers soon learned that other qualities—

For some people, a perceived relationship with God functions as do other attachments, by providing a secure base for exploration and a safe haven when threatened (Granqvist et al., 2010; Kirkpatrick, 1999).

Human infants, too, become attached to parents who are soft and warm and who rock, feed, and pat. Much parent-

imprinting the process by which certain animals form strong attachments during early life.

FAMILIARITY Contact is one key to attachment. Another is familiarity. In many animals, attachments based on familiarity form during a critical period—

Konrad Lorenz (1937) explored this rigid attachment process. He wondered: What would ducklings do if he was the first moving creature they observed? What they did was follow him around: Everywhere that Konrad went, the ducks were sure to go. Although baby birds imprint best to their own species, they also will imprint on a variety of moving objects—

Children—

RETRIEVE IT

Question

What distinguishes imprinting from attachment?

Attachment Differences

4-

What accounts for children’s attachment differences? To answer this question, Mary Ainsworth (1979) designed the strange situation experiment. She observed mother-

Other infants avoid attachment or show insecure attachment, marked either by anxiety or avoidance of trusting relationships. They are less likely to explore their surroundings; they may even cling to their mother. When she leaves, they either cry loudly and remain upset or seem indifferent to her departure and return (Ainsworth, 1973, 1989; Kagan, 1995; van IJzendoorn & Kroonenberg, 1988).

Ainsworth and others found that sensitive, responsive mothers—

Although remembered by some as the researcher who tortured helpless monkeys, Harry Harlow defended his methods: “Remember, for every mistreated monkey there exist a million mistreated children,” he said, expressing the hope that his research would sensitize people to child abuse and neglect. “No one who knows Harry’s work could ever argue that babies do fine without companionship, that a caring mother doesn’t matter,” noted Harlow biographer Deborah Blum (2002, p. 307). “And since we . . . didn’t fully believe that before Harry Harlow came along, then perhaps we needed—

So, caring parents matter. But is attachment style the result of parenting? Or are other factors also at work?

temperament a person’s characteristic emotional reactivity and intensity.

TEMPERAMENT AND ATTACHMENT How does temperament—a person’s characteristic emotional reactivity and intensity—

Shortly after birth, some babies are noticeably difficult—

IMMERSIVE LEARNING Consider how researchers have studied temperament and personality with LaunchPad's How Would You Know If Personality Runs in the Genes?

IMMERSIVE LEARNING Consider how researchers have studied temperament and personality with LaunchPad's How Would You Know If Personality Runs in the Genes?

Temperament differences typically persist. Consider:

The most emotionally reactive newborns tended also to be the most reactive 9-

month- olds (Wilson & Matheny, 1986; Worobey & Blajda, 1989). Exceptionally shy 6-

month- olds often were still shy as 13- year- olds; over 4 in 10 children rated as consistently shy developed anxiety problems in adolescence (Prior et al., 2000). Page 141Emotionally intense preschoolers have tended to be relatively intense young adults (Larsen & Diener, 1987). In one long-

term study of more than 900 New Zealanders, emotionally reactive and impulsive 3- year- olds developed into somewhat more impulsive, aggressive, and conflict- prone 21- year- olds (Caspi, 2000). Identical twins, more than fraternal twins, often have similar temperaments (Fraley & Tancredy, 2012; Kandler et al., 2013).

Parenting studies that neglect such inborn differences, noted Judith Harris (1998), do the equivalent of “comparing foxhounds reared in kennels with poodles reared in apartments.” To separate the effects of nature and nurture on attachment, we would need to vary parenting while controlling temperament. (Pause and think: If you were the researcher, how might you have done this?)

Dutch researcher Dymphna van den Boom’s solution was to randomly assign 100 temperamentally difficult 6-

As many of these examples indicate, researchers have more often studied mother care than father care, but fathers are more than just mobile sperm banks. Despite the widespread attitude that “fathering a child” means impregnating, and “mothering” means nurturing, nearly 100 studies worldwide have shown that a father’s love and acceptance are comparable with a mother’s love in predicting an offspring’s health and well-

Dual Parenting Facts

| Some hard facts about declining father care: | Some encouraging findings: |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

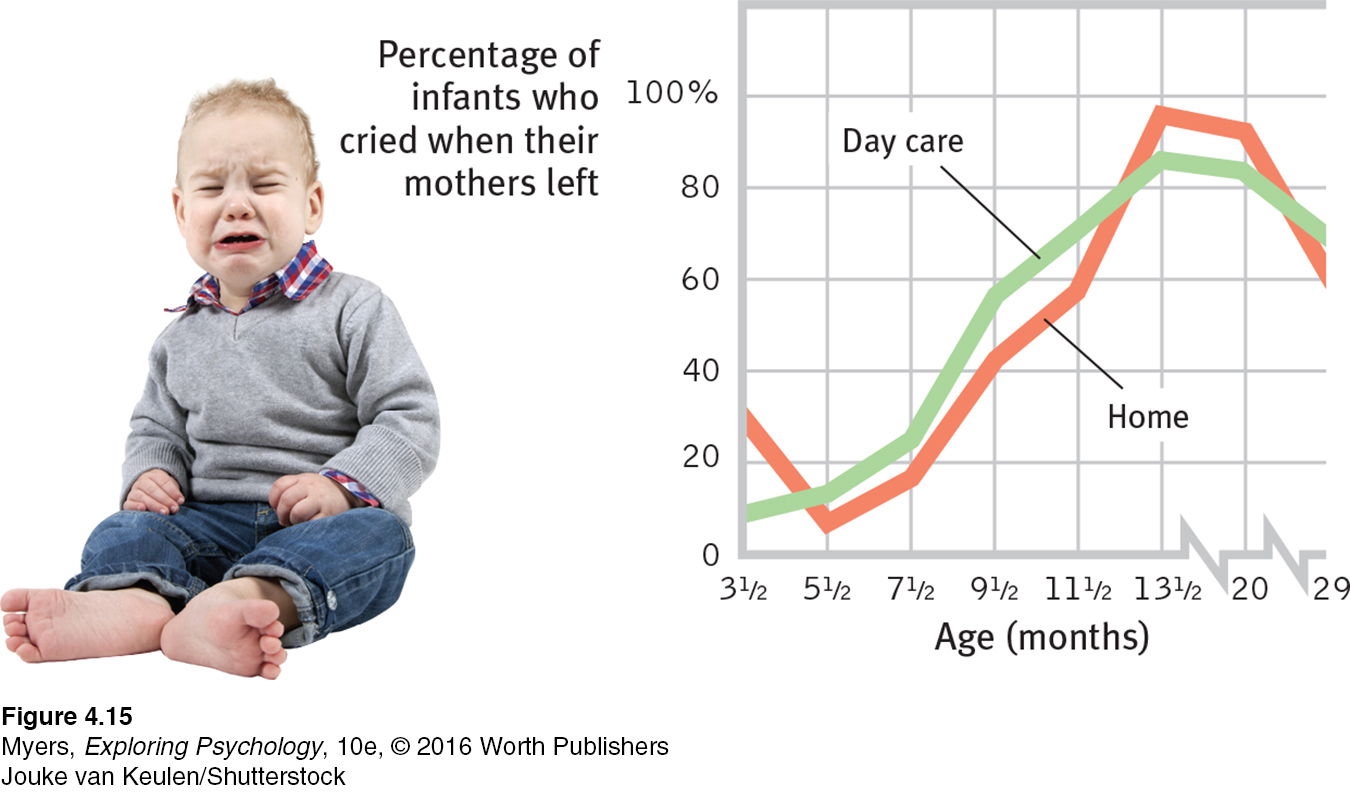

Children’s anxiety over separation from parents peaks at around 13 months, then gradually declines (FIGURE 4.15). This happens whether they live with one parent or two, are cared for at home or in a day-

“Out of the conflict between trust and mistrust, the infant develops hope, which is the earliest form of what gradually becomes faith in adults.”

Erik Erikson (1983)

basic trust according to Erik Erikson, a sense that the world is predictable and trustworthy; said to be formed during infancy by appropriate experiences with responsive caregivers.

ATTACHMENT STYLES AND LATER RELATIONSHIPS Developmental theorist Erik Erikson (1902-

Many researchers now believe that our early attachments form the foundation for our adult relationships (Birnbaum et al., 2006; Fraley et al., 2013). People who report secure relationships with their parents tend to enjoy secure friendships (Gorrese & Ruggieri, 2012). When leaving home to attend college—

Feeling insecurely attached to others may take either of two main forms (Fraley et al., 2011). With insecure-

Adult attachment styles affect relationships with romantic partners and one’s own children (Hadden et al., 2014; Jones et al., 2015). An anxious attachment style hinders social connections. An avoidant style decreases commitment and increases conflict (DeWall et al., 2011; Li & Chan, 2012). But say this for those (nearly half of all people) who exhibit wary, insecure attachments: Anxious or avoidant tendencies have helped our groups detect or escape dangers (Ein-

Deprivation of Attachment

4-

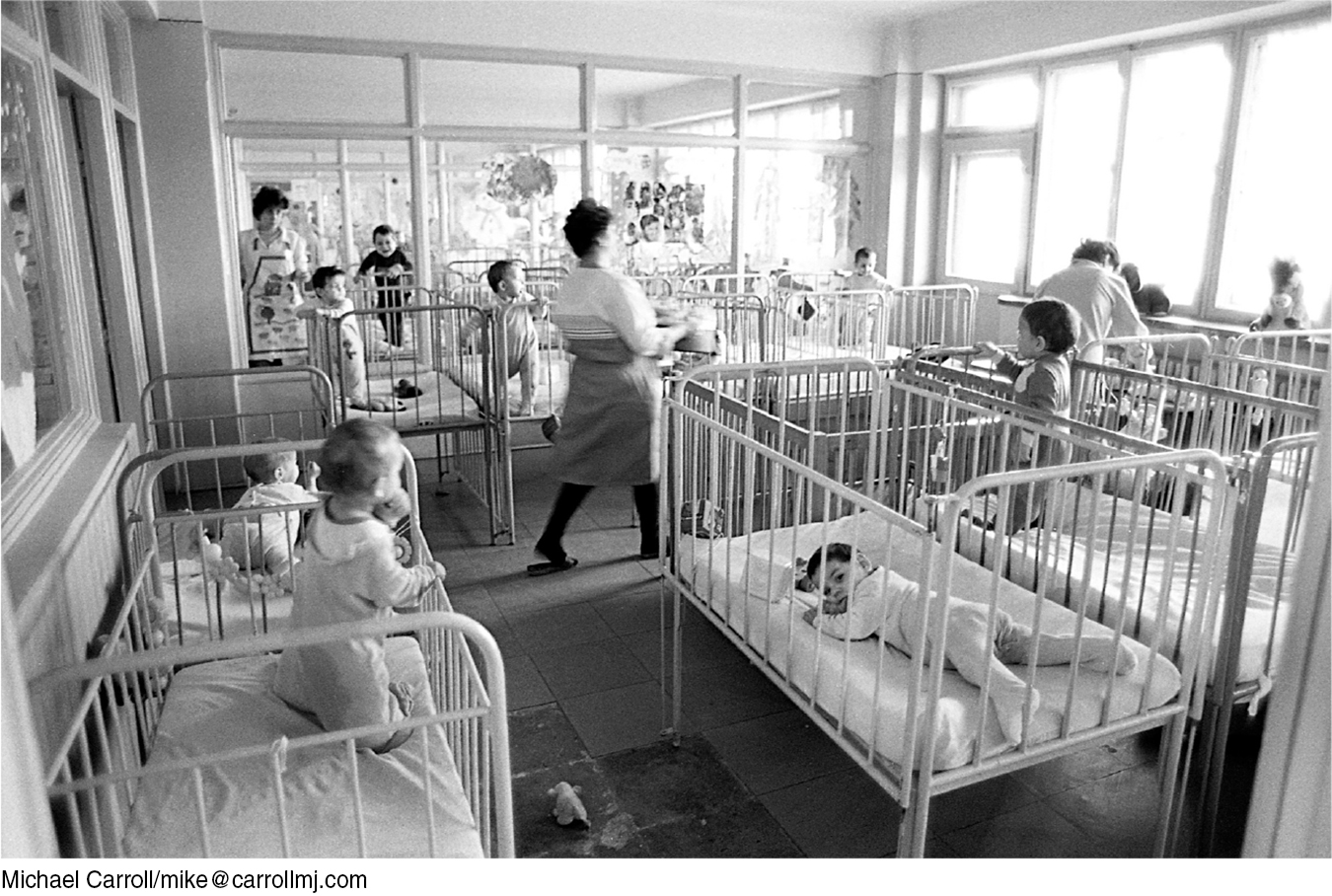

If secure attachment fosters social trust, what happens when circumstances prevent a child from forming attachments? In all of psychology, there is no sadder research literature. Babies locked away at home under conditions of abuse or extreme neglect are often withdrawn, frightened, even speechless. The same is true of those raised in institutions without the stimulation and attention of a regular caregiver, as was tragically illustrated during the 1970s and 1980s in Romania. Having decided that economic growth for his impoverished country required more human capital, Nicolae Ceauşescu, Romania’s Communist dictator, outlawed contraception, forbade abortion, and taxed families with fewer than five children. The birthrate skyrocketed. But unable to afford the children they had been coerced into having, many families abandoned them to government-

“What is learned in the cradle, lasts to the grave.”

French proverb

Most children growing up under adversity (as did the surviving children of the Holocaust) are resilient; they withstand the trauma and become well-

But those who experience enduring abuse don’t bounce back so readily. The Harlows’ monkeys raised in total isolation, without even an artificial mother, bore lifelong scars. As adults, when placed with other monkeys their age, they either cowered in fright or lashed out in aggression. When they reached sexual maturity, most were incapable of mating. If artificially impregnated, females often were neglectful, abusive, even murderous toward their first-

In humans, too, the unloved may become the unloving. Most abusive parents—

Although most abused children do not later become violent criminals or abusive parents, extreme early trauma may nevertheless leave footprints on the brain. Like battle-

“Stress can set off a ripple of hormonal changes that permanently wire a child’s brain to cope with a malevolent world.”

Abuse researcher Martin Teicher (2002)

Such findings help explain why young children who have survived severe or prolonged physical abuse, childhood sexual abuse, bullying, or wartime atrocities are at increased risk for health problems, psychological disorders, substance abuse, and criminality (Lereya et al., 2015; Nanni et al., 2012; Trickett et al., 2011; Whitelock et al., 2013; Wolke et al., 2013). In one national study of 43,093 adults, 8 percent reported experiencing physical abuse at least fairly often before age 18 (Sugaya et al., 2012). Among these, 84 percent had experienced at least one psychiatric disorder. Moreover, the greater the abuse, the greater the odds of anxiety, depression, and substance use disorder, and of attempted suicide. Abuse victims are at considerable risk for depression if they carry a gene variation that spurs stress-

We adults also suffer when our attachment bonds are severed. Whether through death or separation, a break produces a predictable sequence. Agitated preoccupation with the lost partner is followed by deep sadness and, eventually, the beginnings of emotional detachment and a return to normal living (Hazan & Shaver, 1994). Newly separated couples who have long ago ceased feeling affection are sometimes surprised at their desire to be near the former partner. Detaching is a process, not an event.

Parenting Styles

4-

Some parents spank, some reason. Some are strict, some are lax. Some show little affection, some liberally hug and kiss. Do such differences in parenting styles affect children?

The most heavily researched aspect of parenting has been how, and to what extent, parents seek to control their children. Investigators have identified three parenting styles:

1. Authoritarian parents are coercive. They impose rules and expect obedience: “Don’t interrupt.” “Keep your room clean.” “Don’t stay out late or you’ll be grounded.” “Why? Because I said so.”

2. Permissive parents are unrestraining. They make few demands and use little punishment. They may be indifferent, unresponsive, or unwilling to set limits.

3. Authoritative parents are confrontive. They are both demanding and responsive. They exert control by setting rules, but, especially with older children, they encourage open discussion and allow exceptions.

See LaunchPad’s Video: Correlational Studies, below, for a helpful tutorial animation about correlational research design.

See LaunchPad’s Video: Correlational Studies, below, for a helpful tutorial animation about correlational research design.

Too hard, too soft, and just right, these styles have been called, especially by pioneering researcher Diana Baumrind and her followers. Research indicates that children with the highest self-

A word of caution: The association between certain parenting styles (being firm but open) and certain childhood outcomes (social competence) is correlational. Correlation is not causation. Perhaps you can imagine possible explanations for this parenting-

Parents who struggle with conflicting advice should also remember that all advice reflects the advice-

CULTURE AND CHILD RAISING Child-

In recent years, some Western parents have gone further, telling their children, “You are more special than other children” (Brummelman et al., 2015). (Not surprisingly, these puffed-

Children across time and place have thrived under various child-

Many Asian and African cultures place less value on independence and more on a strong sense of family self—

“You are the bows from which your children as living arrows are sent forth.”

Kahlil Gibran, The Prophet, 1923

Such diversity in child raising cautions us against presuming that our culture’s way is the only way to raise children successfully. One thing is certain, however: Whatever our culture, the investment in raising a child buys many years not only of joy and love but also of worry and irritation. In a national Gallup survey, adults with children under 18 at home were more likely than other adults to report smiling and laughing “a lot yesterday”—but also to have experienced stress “a lot of the day yesterday” (Witters, 2014). Yet for most people who become parents, a child is one’s biological and social legacy—

RETRIEVE IT

Question

The three parenting styles have been called “too hard, too soft, and just right.” Which one is “too hard,” which one “too soft,” and which one “just right,” and why?

REVIEW Infancy and Childhood

Learning Objectives

Test Yourself by taking a moment to answer each of these Learning Objective Questions (repeated here from within the chapter). Research suggests that trying to answer these questions on your own will improve your long-

Question

4-

Question

4-

Question

4-

Question

4-

Question

4-

Question

4-

Question

4-

Terms and Concepts to Remember

Test yourself on these terms.

Question

maturation (p. 127) critical period (p. 128) cognition (p. 130) schema (p. 130) assimilation (p. 130) accommodation (p. 130) sensorimotor stage (p. 130) object permanence (p. 130) preoperational stage (p. 131) conservation (p. 132) egocentrism (p. 132) theory of mind (p. 133) concrete operational stage (p. 133) formal operational stage (p. 133) autism spectrum disorder (ASD) (p. 135) stranger anxiety (p. 138) attachment (p. 138) imprinting (p. 139) temperament (p. 140) basic trust (p. 142) | the principle (which Piaget believed to be a part of concrete operational reasoning) that properties such as mass, volume, and number remain the same despite changes in the forms of objects. in Piaget's theory, the preoperational child's difficulty taking another's point of view. biological growth processes that enable orderly changes in behavior, relatively uninfluenced by experience. according to Erik Erikson, a sense that the world is predictable and trustworthy; said to be formed during infancy by appropriate experiences with responsive caregivers. the process by which certain animals form strong attachments during early life. people's ideas about their own and others' mental states— interpreting our new experiences in terms of our existing schemas. adapting our current understandings (schemas) to incorporate new information. in Piaget's theory, the stage (from about 2 to about 6 or 7 years of age) during which a child learns to use language but does not yet comprehend the mental operations of concrete logic. an emotional tie with another person; shown in young children by their seeking closeness to the caregiver and showing distress on separation. a concept or framework that organizes and interprets information. a disorder that appears in childhood and is marked by significant deficiencies in communication and social interaction, and by rigidly fixated interests and repetitive behaviors. an optimal period early in the life of an organism when exposure to certain stimuli or experiences produces normal development. the fear of strangers that infants commonly display, beginning by about 8 months of age. the awareness that things continue to exist even when not perceived. in Piaget's theory, the stage (from birth to nearly 2 years of age) during which infants know the world mostly in terms of their sensory impressions and motor activities. in Piaget's theory, the stage of cognitive development (normally beginning about age 12) during which people begin to think logically about abstract concepts. a person's characteristic emotional reactivity and intensity. in Piaget's theory, the stage of cognitive development (from about 7 to 11 years of age) during which children gain the mental operations that enable them to think logically about concrete events. all the mental activities associated with thinking, knowing, remembering, and communicating. |

Experience the Testing Effect

Test yourself repeatedly throughout your studies. This will not only help you figure out what you know and don’t know; the testing itself will help you learn and remember the information more effectively thanks to the testing effect.

Question 4.6

1. Stroke a newborn's cheek and the infant will root for a nipple. This illustrates

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 4.7

2. Between ages 3 and 6, the human brain experiences the greatest growth in the lobes, which enable rational planning and aid memory.

Question 4.8

3. Which of the following is true of motor-skill development?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 4.9

4. Why can't we consciously recall how we learned to walk when we were infants?

Question 4.10

5. Use Piaget's first three stages of cognitive development to explain why young children are not just miniature adults in the way they think.

Question 4.11

6. Although Piaget's stage theory continues to inform our understanding of children's thinking, many researchers believe that

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 4.12

7. An 8-month-old infant who reacts to a new babysitter by crying and clinging to his father's shoulder is showing .

Question 4.13

8. In a series of experiments, the Harlows found that monkeys raised with artificial mothers tended, when afraid, to cling to their cloth mother, rather than to a wire mother holding the feeding bottle. Why was this finding important?

Use  to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in

to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in  .

.