How do we create meaning from the blizzard of sensory stimuli that bombards our body 24 hours a day? Meanwhile, in a silent, cushioned, inner world, our brain floats in utter darkness. By itself, it sees nothing. It hears nothing. It feels nothing. So, how does the world out there get in? To phrase the question scientifically: How do we construct our representations of the external world? How do a campfire’s flicker, crackle, and smoky scent activate neural connections? And how, from this living neurochemistry, do we create our conscious experience of the fire’s motion and temperature, its aroma and beauty? In search of answers, let’s examine the basics of sensation and perception, and look at some processes that cut across all our sensory systems.

6-

sensation the process by which our sensory receptors and nervous system receive and represent stimulus energies from our environment.

perception the process of organizing and interpreting sensory information, enabling us to recognize meaningful objects and events.

Heather Sellers’ curious mix of “perfect vision” and face blindness illustrates the distinction between sensation and perception. When she looks at a friend, her sensation is normal: Her sensory receptors detect the same information yours would, and her nervous system transmits that information to her brain. Her perception—the processes by which her brain organizes and interprets sensory input—

In our everyday experiences, sensation and perception blend into one continuous process.

bottom-up processing analysis that begins with the sensory receptors and works up to the brain’s integration of sensory information.

top-down processing information processing guided by higher-

Our bottom-up processing starts at the sensory receptors, which receive sensory input, and works up to higher levels of processing.

Our top-down processing creates meaning from this sensory input by drawing on our experience and expectations.

As our brain absorbs the information in FIGURE 6.1, bottom-

Transduction

6-

Every second of every day, our sensory systems perform an amazing feat: They convert one form of energy into another. Vision processes light energy. Hearing processes sound waves. All our senses

receive sensory stimulation, often using specialized receptor cells.

transform that stimulation into neural impulses.

deliver the neural information to our brain.

transduction conversion of one form of energy into another. In sensation, the transforming of stimulus energies, such as sights, sounds, and smells, into neural impulses our brain can interpret.

The process of converting one form of energy into another that our brain can use is called transduction. Later in this chapter, we’ll focus on individual sensory systems. How do we see? Hear? Feel pain? Taste? Smell? Keep our balance? In each case, one of our sensory systems receives, transforms, and delivers the information to our brain.

Let’s explore some strengths and weaknesses in our ability to detect and interpret stimuli in the vast sea of energy around us.

RETRIEVE IT

Question

What is the rough distinction between sensation and perception?

Thresholds

6-

At this moment, we are being struck by X-

The shades on our own senses are open just a crack, allowing us a restricted awareness of this vast sea of energy. But for our needs, this is enough.

Absolute Thresholds

To some kinds of stimuli we are exquisitely sensitive. Standing atop a mountain on an utterly dark, clear night, most of us could see a candle flame atop another mountain 30 miles away. We could smell a single drop of perfume in a three-

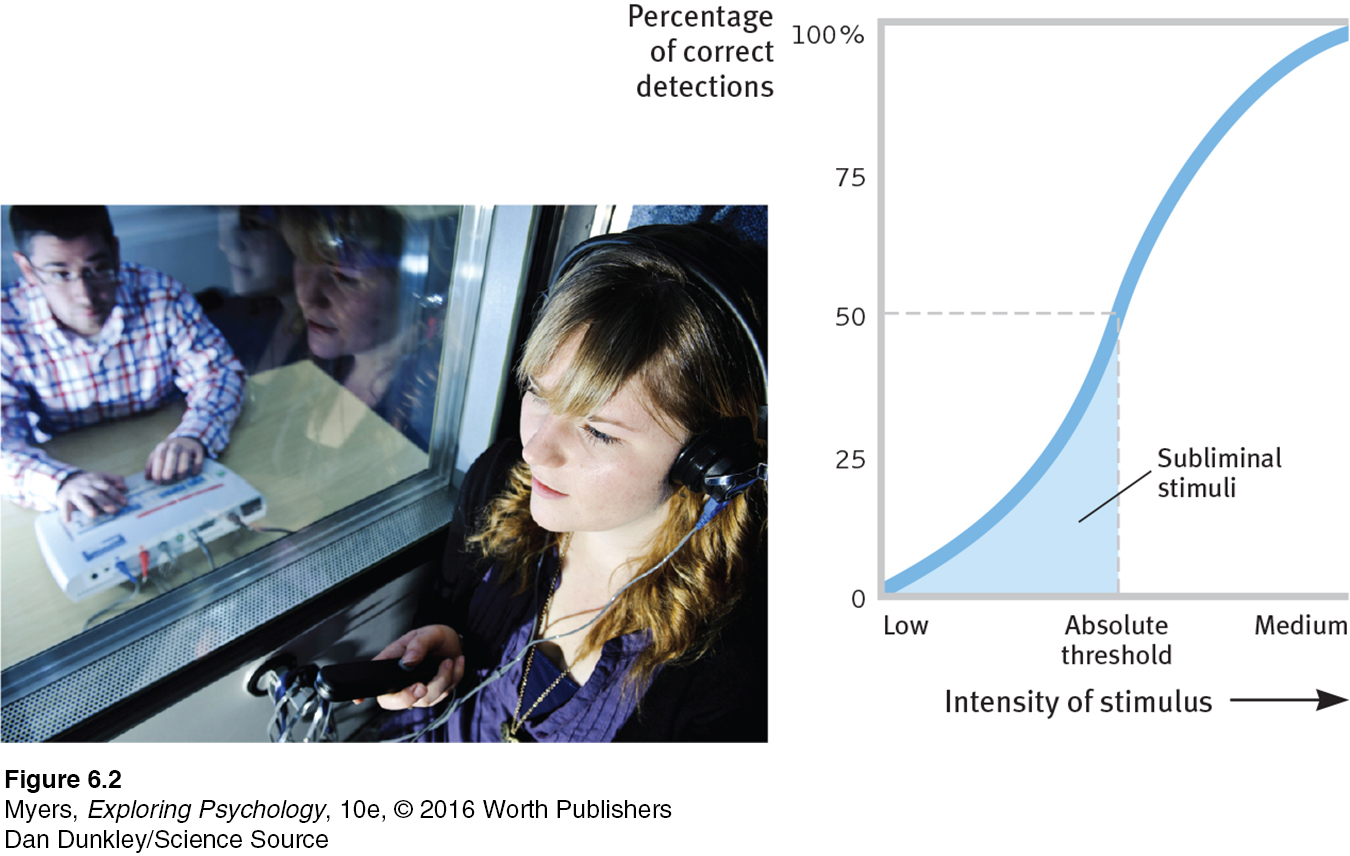

absolute threshold the minimum stimulus energy needed to detect a particular stimulus 50 percent of the time.

German scientist and philosopher Gustav Fechner (1801–

signal detection theory a theory predicting how and when we detect the presence of a faint stimulus (signal) amid background stimulation (noise). Assumes there is no single absolute threshold and that detection depends partly on a person’s experience, expectations, motivation, and alertness.

Detecting a weak stimulus, or signal (such as a hearing-

subliminal below one’s absolute threshold for conscious awareness.

priming the activation, often unconsciously, of certain associations, thus predisposing one’s perception, memory, or response.

See LaunchPad's Video: Experiments, below, for a helpful tutorial animation about this type of research method.

See LaunchPad's Video: Experiments, below, for a helpful tutorial animation about this type of research method.

Stimuli you cannot consciously detect 50 percent of the time are subliminal—below your absolute threshold (see FIGURE 6.2). Under certain conditions, you can still be affected by stimuli so weak that you don’t consciously notice them. An unnoticed image or word can reach your visual cortex and briefly prime your response to a later question. In a typical experiment, the image or word is quickly flashed, then replaced by a masking stimulus that interrupts the brain’s processing before conscious perception (Herring et al., 2013; Van den Bussche et al., 2009). In one such experiment, researchers monitored brain activity as they primed people with either unperceived action words (such as go and start) or inaction words (such as still and stop). Without any conscious awareness, the inaction words automatically evoked brain activity associated with inhibiting behavior (Hepler & Albarracin, 2013).

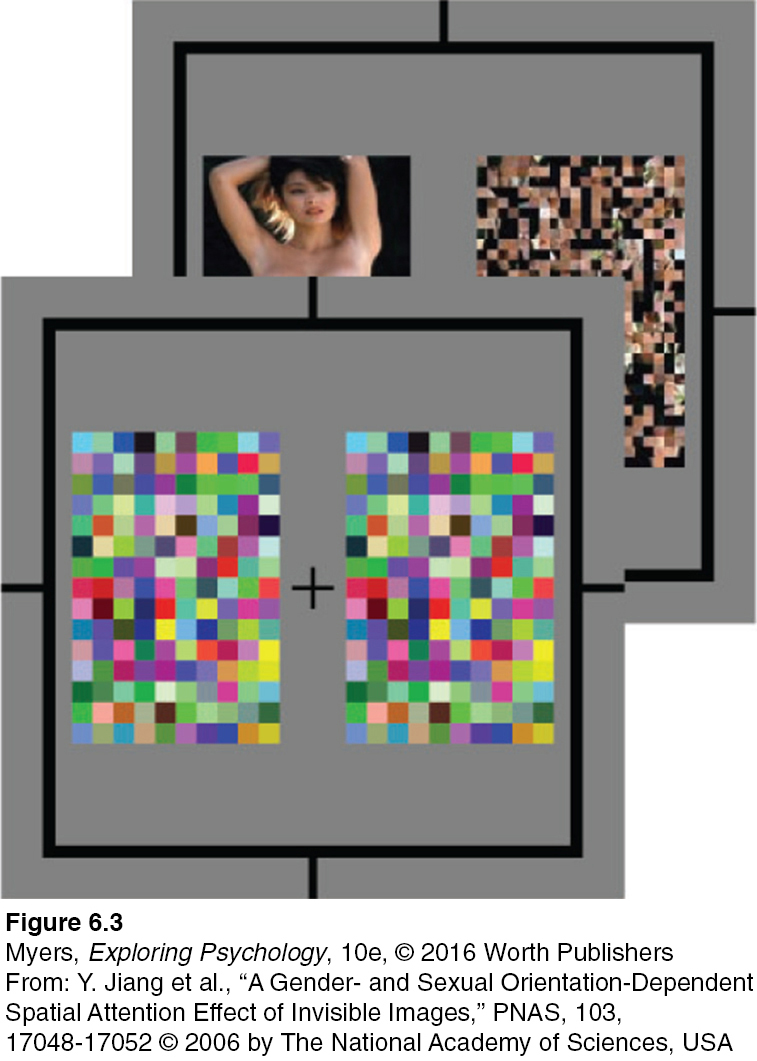

Another priming experiment illustrated the deep reality of sexual orientation. As people gazed at the center of a screen, a photo of a nude person was flashed on one side and a scrambled version of the photo on the other side (Jiang et al., 2006). Because the nude images were immediately masked by a colored checkerboard, viewers consciously perceived nothing but flashes of color and so were unable to state on which side the nude had appeared. To test whether this unseen image had unconsciously attracted their attention, the experimenters then flashed a geometric figure to one side or the other. This, too, was quickly followed by a masking stimulus. When asked to give the figure’s angle, straight men guessed more accurately when it appeared where a nude woman had been a moment earlier (FIGURE 6.3). Gay men (and straight women) guessed more accurately when the geometric figure replaced a nude man. As other experiments confirm, we can evaluate a stimulus even when we are not consciously aware of it—

“The heart has its reasons which reason does not know.”

Pascal, Pensées, 1670

How can we feel or respond to what we do not know and cannot describe? An imperceptibly brief stimulus often triggers a weak response that can be detected by brain scanning (Blankenburg et al., 2003; Haynes & Rees, 2005, 2006). The stimulus may reach consciousness only when it triggers synchronized activity in multiple brain areas (Dehaene, 2009, 2014). Such experiments reveal the dual-

So can we be controlled by subliminal messages? For more on that question, see Thinking Critically About: Subliminal Persuasion.

Difference Thresholds

To function effectively, we need absolute thresholds low enough to allow us to detect important sights, sounds, textures, tastes, and smells. We also need to detect small differences among stimuli. A musician must detect minute discrepancies when tuning an instrument. Parents must detect the sound of their own child’s voice amid other children’s voices. I [DM] noticed while living two years in Scotland that sheep baas all sound alike to my ears. But not to those of ewes, who, after shearing, will streak directly to the baa of their lamb amid the chorus of other distressed lambs.

difference threshold the minimum difference between two stimuli required for detection 50 percent of the time. We experience the difference threshold as a just noticeable difference (or jnd).

Weber’s law the principle that, to be perceived as different, two stimuli must differ by a constant minimum percentage (rather than a constant amount).

The difference threshold (or the just noticeable difference [jnd]) is the minimum difference a person can detect between any two stimuli half the time. That difference threshold increases with the size of the stimulus. If we listen to our music at 40 decibels, we might detect an added 5 decibels. But if we increase the volume to 110 decibels, we probably won’t detect a 5-

THINKING CRITICALLY ABOUT

Subliminal Persuasion

6-

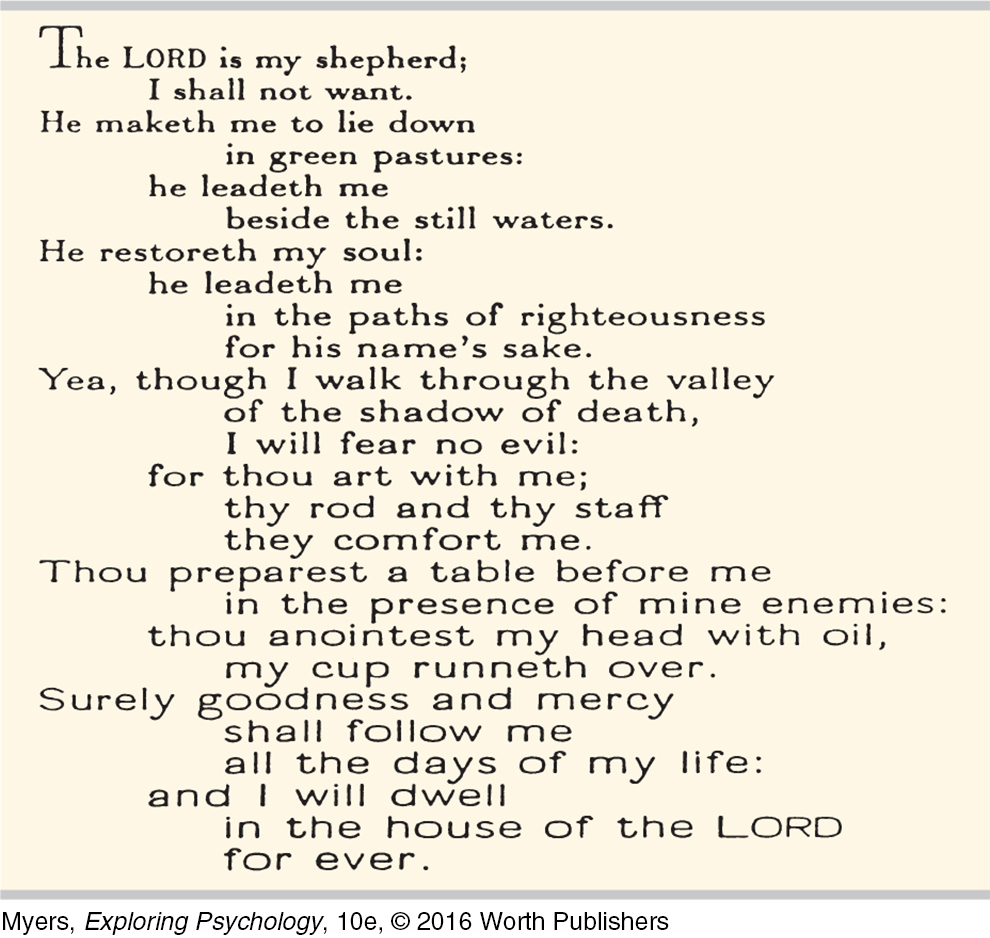

Hoping to penetrate our unconscious, entrepreneurs offer audio and video programs to help us lose weight, stop smoking, or improve our memories. Soothing ocean sounds may mask messages we cannot consciously hear: “I am thin”; “Smoke tastes bad”; or “I do well on tests—

As we have seen, subliminal sensation is a fact. Remember that an “absolute” threshold is merely the point at which we can consciously detect a stimulus half the time. At or slightly below this threshold, we will still consciously detect the stimulus some of the time.

But does this mean that claims of subliminal persuasion are also facts? The near-

To test whether subliminal recordings have this enduring effect, Anthony Greenwald and his colleagues (1991, 1992) randomly assigned university students to listen daily for five weeks to commercial subliminal messages claiming to improve either self-

Were the recordings effective? Students’ test scores for self-

Over a decade, Greenwald conducted 16 double-

RETRIEVE IT

Question

Using sound as your example, explain how these concepts differ: absolute threshold, subliminal stimulation, and difference threshold.

Sensory Adaptation

6-

sensory adaptation diminished sensitivity as a consequence of constant stimulation.

Entering your neighbors’ living room, you smell a musty odor. You wonder how they endure it, but within minutes you no longer notice it. Sensory adaptation has come to your rescue. When we are constantly exposed to an unchanging stimulus, we typically become less aware of it because our nerve cells fire less frequently. (To experience sensory adaptation, move your watch up your wrist an inch. You will feel it—

“We need above all to know about changes; no one wants or needs to be reminded 16 hours a day that his shoes are on.”

Neuroscientist David Hubel (1979)

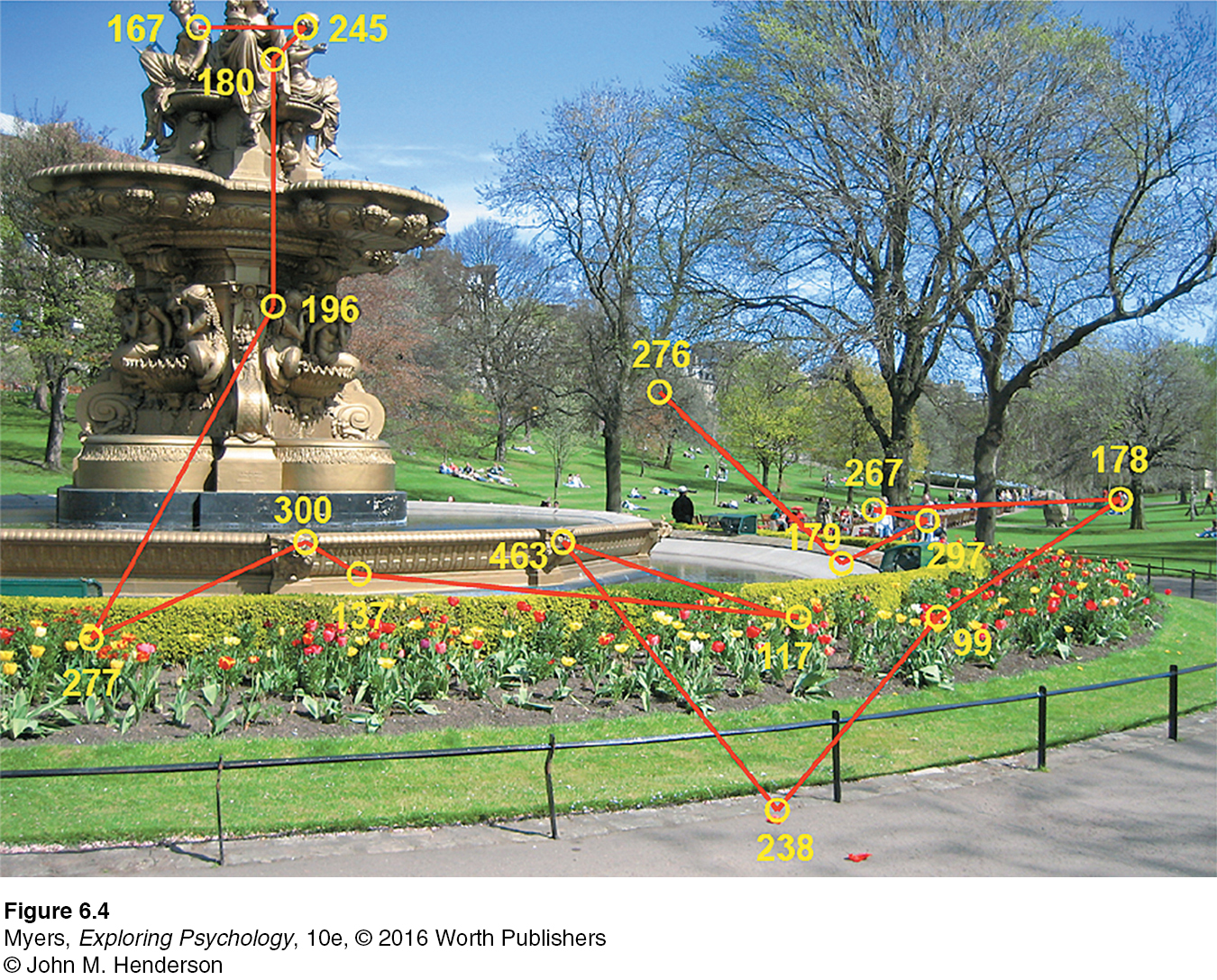

Why, then, if we stare at an object without flinching, does it not vanish from sight? Because, unnoticed by us, our eyes are always moving (FIGURE 6.4). This continual flitting from one spot to another ensures that stimulation on the eyes’ receptors continually changes.

What if we actually could stop our eyes from moving? Would sights seem to vanish, as odors do? To find out, psychologists have devised ingenious instruments that maintain a constant image on the eye’s inner surface. Imagine that we have fitted a volunteer, Mary, with one of these instruments—

If we project images through this instrument, what will Mary see? At first, she will see the complete image. But within a few seconds, as her sensory system begins to fatigue, things get weird. Bit by bit, the image vanishes, only to reappear and then disappear—

Although sensory adaptation reduces our sensitivity to constant stimulation, it offers an important benefit: freedom to focus on informative changes in our environment without being distracted by background chatter. Stinky or heavily perfumed people don’t notice their odor because, like you and me, they adapt to what’s constant and detect only change. Our sensory receptors are alert to novelty; bore them with repetition and they free our attention for more important things. The point to remember: We perceive the world not exactly as it is, but as it is useful for us to perceive it.

Our sensitivity to changing stimulation helps explain television’s attention-

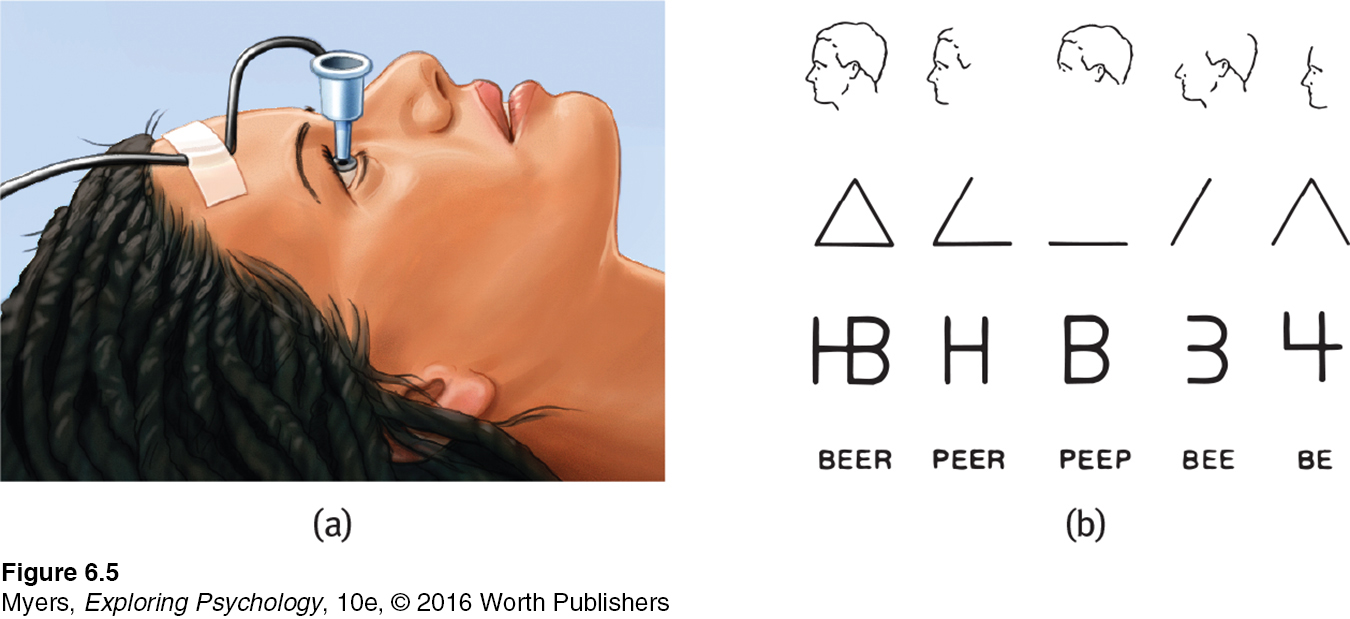

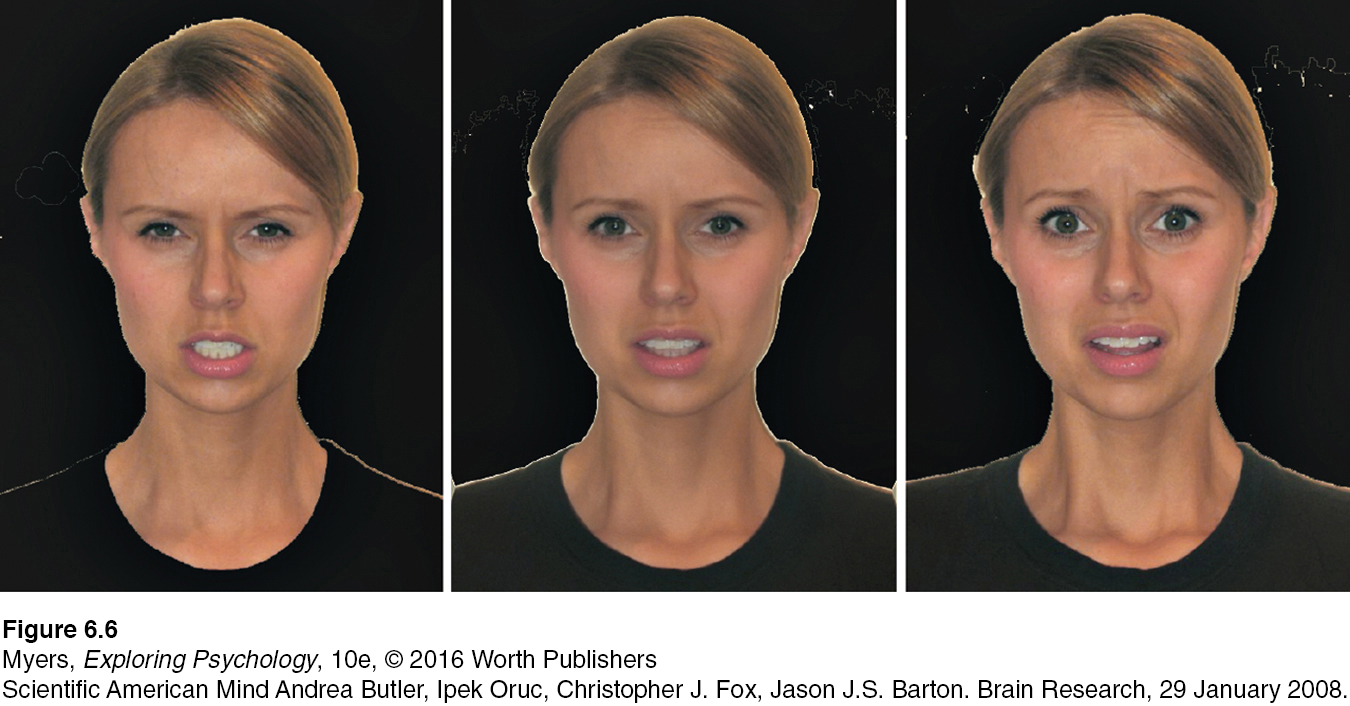

Sensory adaptation even influences how we perceive emotions. By creating a 50-

Sensory adaptation and sensory thresholds are important ingredients in our perceptions of the world around us. Much of what we perceive comes not just from what’s “out there,” but also from what’s behind our eyes and between our ears.

RETRIEVE IT

Question

Why is it that after wearing shoes for a while, you cease to notice them (until questions like this draw your attention back to them)?

Perceptual Set

6-

perceptual set a mental predisposition to perceive one thing and not another.

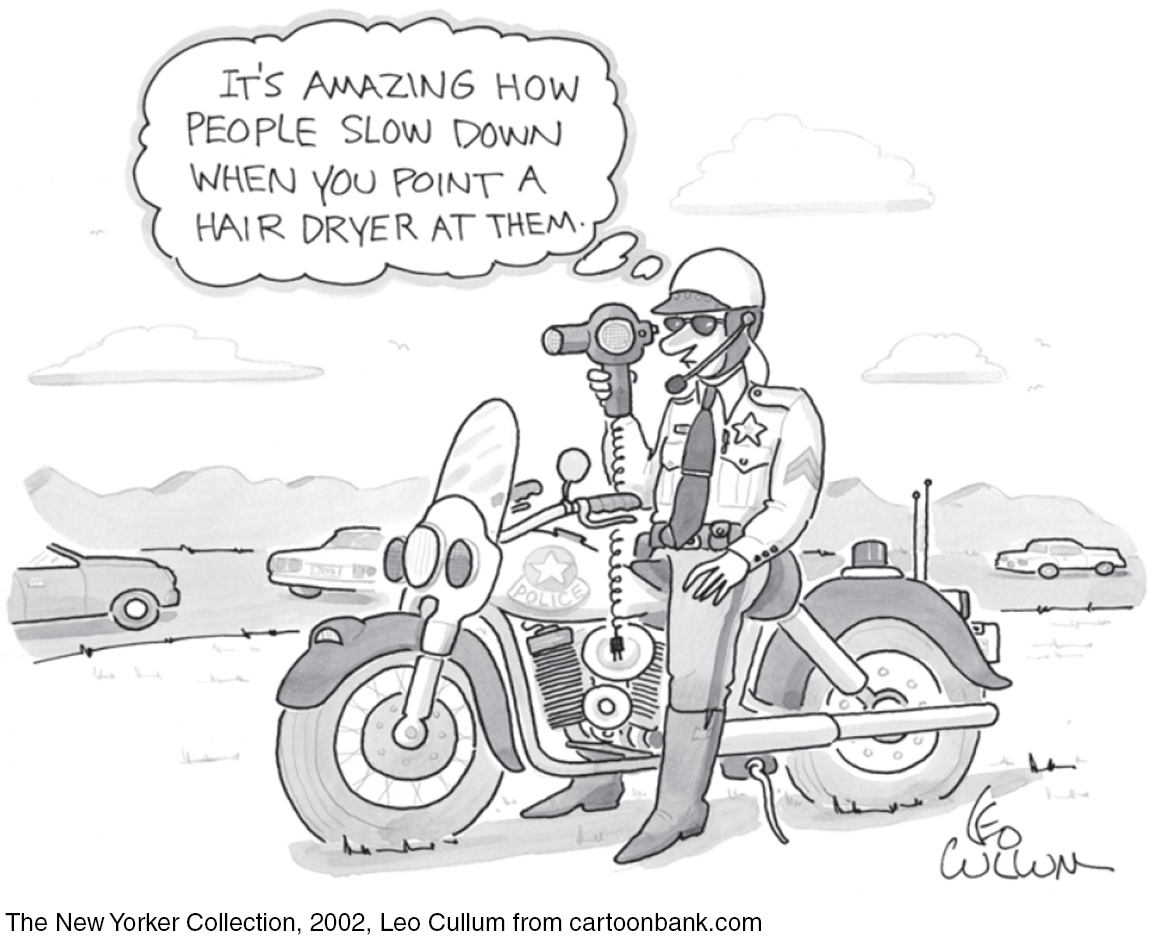

To see is to believe. As we less fully appreciate, to believe is to see. Through experience, we come to expect certain results. Those expectations may give us a perceptual set—a set of mental tendencies and assumptions that affects, top-

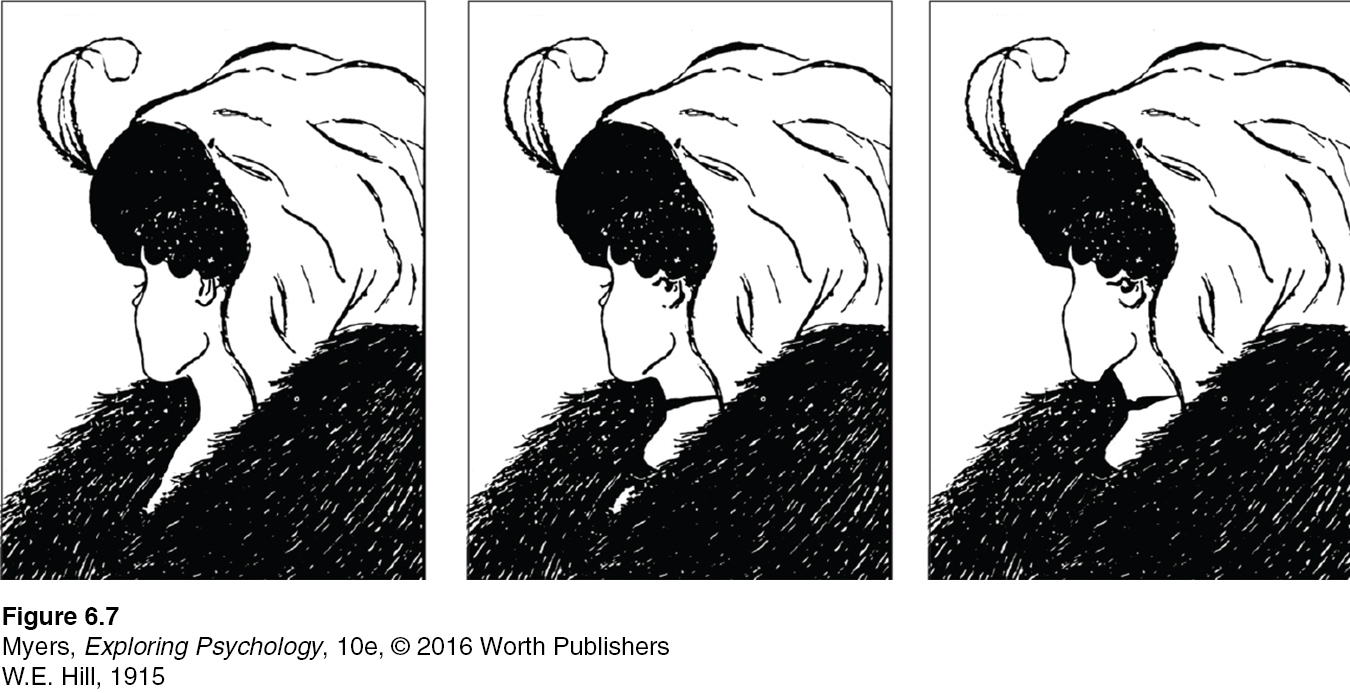

Consider: Is the center image in FIGURE 6.7 below an old or young woman? What we see in such a drawing can be influenced by first looking at either of the two unambiguous versions (Boring, 1930).

There

Are Two

Errors in The

The Title Of

This Book

Book by Robert M. Martin, 2011

In the note above, did you perceive what you expected in this title—

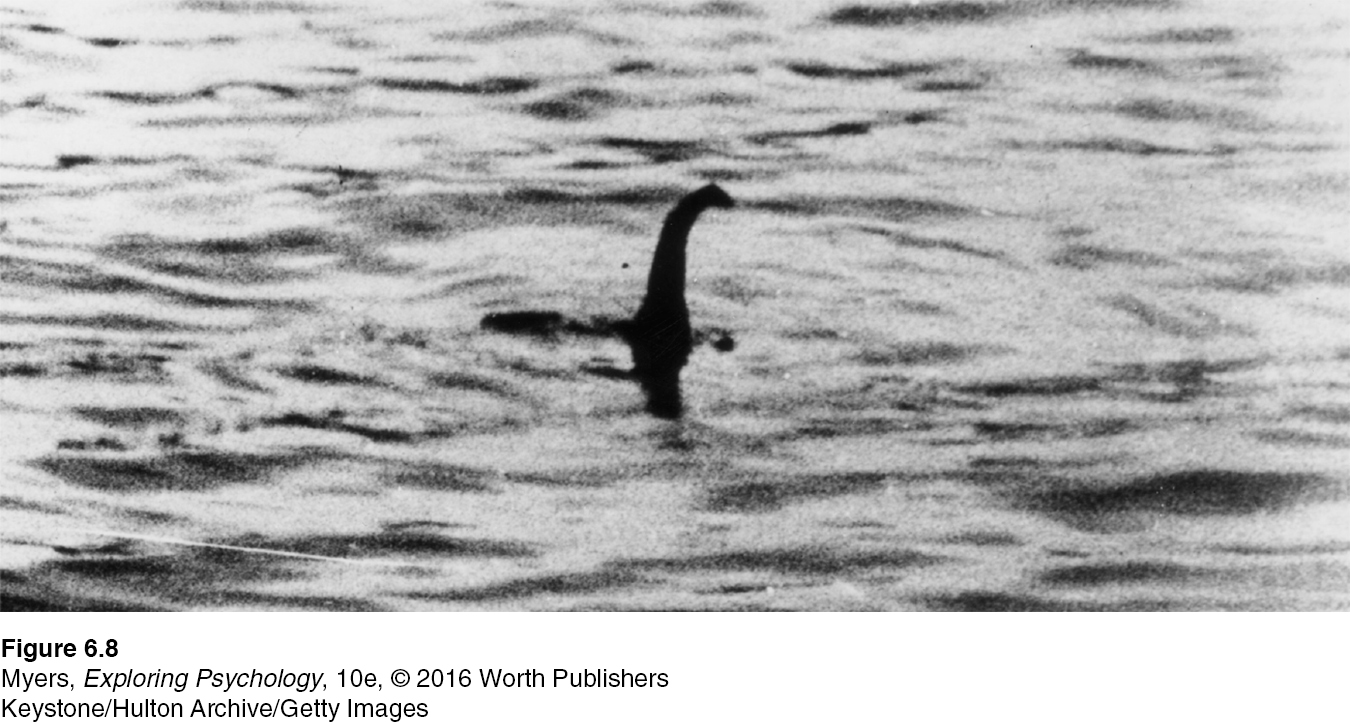

Everyday examples of perceptual set abound. In 1972, a British newspaper published unretouched photographs of a “monster” in Scotland’s Loch Ness—

Perceptual set can also affect what we hear. Consider the kindly airline pilot who, on a takeoff run, looked over at his sad co-

Perceptual set similarly affects taste. One experiment invited bar patrons to sample free beer (Lee et al., 2006). The tasters preferred the brand-

What determines our perceptual set? Through experience we form concepts, or schemas, that organize and interpret unfamiliar information. Our preexisting schemas for monsters and tree branches influence how we apply top-

“We hear and apprehend only what we already half know.”

Henry David Thoreau, Journal, 1860

In everyday life, stereotypes about gender (another instance of perceptual set) can color perception. Without the obvious cues of pink or blue, people will struggle over whether to call the new baby “he” or “she.” But told an infant is “David,” people (especially children) have perceived “him” as bigger and stronger than if the same infant was called “Diana” (Stern & Karraker, 1989). Some differences, it seems, exist merely in the eyes of their beholders.

Context Effects

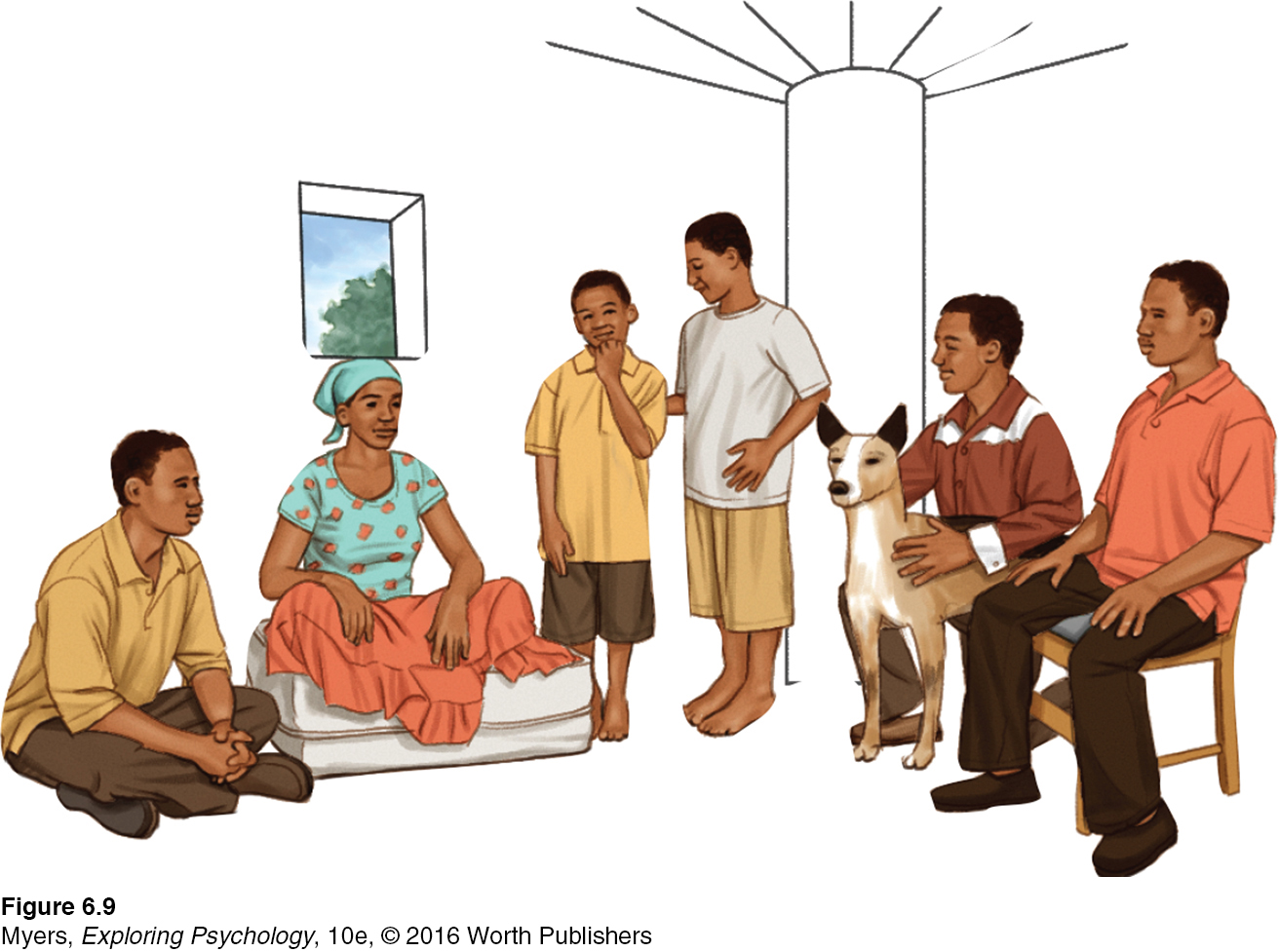

A given stimulus may trigger radically different perceptions, partly because of our differing perceptual set (FIGURE 6.9), but also because of the immediate context. Some examples:

When holding a gun, people become more likely to perceive another person as gun-

toting— a phenomenon that has led to the shooting of some unarmed people who were actually holding their phone or wallet (Witt & Brockmole, 2012). Imagine hearing a noise interrupted by the words “eel is on the wagon.” Likely, you would actually perceive the first word as wheel. Given “eel is on the orange,” you would more likely hear peel. This curious phenomenon suggests that the brain can work backward in time to allow a later stimulus to determine how we perceive an earlier one. The context creates an expectation that, top-

down, influences our perception (Grossberg, 1995). How is the woman in FIGURE 6.10 feeling?

RETRIEVE IT

Question

Does perceptual set involve bottom-

Motivation and Emotion

Perceptions are also influenced, top-

Hearing sad rather than happy music can predispose people to perceive a sad meaning in spoken homophonic words—

walking destinations look farther away to those fatigued by prior exercise.

a hill looks steeper to those who are wearing a heavy backpack or have just been exposed to sad, heavy classical music rather than light, bouncy music. As with so many of life’s challenges, a hill also seems less steep to those who feel others understand them (Oishi et al., 2013).

a target seems farther away to those throwing a heavy rather than a light object at it.

a softball appears bigger when you are hitting well. Jessica Witt and Proffitt (2005) observed this after asking players to choose a circle the size of the ball they had just hit well or poorly. (There’s also a reciprocal phenomenon: Seeing a target as bigger—

as happens when athletes focus directly on a target— improves performance [Witt et al., 2012].)

Motives also matter. Desired objects, such as a water bottle when thirsty, seem closer (Balcetis & Dunning, 2010). This perceptual bias energizes our going for it. Our motives also direct our perception of ambiguous stimuli.

“When you’re hitting the ball, it comes at you looking like a grapefruit. When you’re not, it looks like a black-

Former major league baseball player George Scott

Emotions and motives color our social perceptions, too. People more often perceive solitary confinement, sleep deprivation, and cold temperatures as “torture” when experiencing a small dose of such themselves (Nordgren et al., 2011). Spouses who feel loved and appreciated perceive less threat in stressful marital events—

Learning Objectives

Test Yourself by taking a moment to answer each of these Learning Objective Questions (repeated here from within the chapter). Research suggests that trying to answer these questions on your own will improve your long-

Question

6-

Question

6-

Question

6-

Question

6-

Question

6-

Question

6-

Terms and Concepts to Remember

Test yourself on these terms.

Question

sensation (p. 200) perception (p. 200) bottom- top- transduction (p. 200) absolute threshold (p. 201) signal detection theory (p. 201) subliminal (p. 201) priming (p. 201) difference threshold (p. 202) Weber's law (p. 203) sensory adaptation (p. 204) perceptual set (p. 205) | information processing guided by higher- a theory predicting how and when we detect the presence of a faint stimulus (signal) amid background stimulation (noise). Assumes there is no single absolute threshold and that detection depends partly on a person's experience, expectations, motivation, and alertness. the activation, often unconsciously, of certain associations, thus predisposing one's perception, memory, or response. a mental predisposition to perceive one thing and not another. the minimum stimulus energy needed to detect a particular stimulus 50 percent of the time. below one's absolute threshold for conscious awareness. the process by which our sensory receptors and nervous system receive and represent stimulus energies from our environment. analysis that begins with the sensory receptors and works up to the brain's integration of sensory information. the minimum difference between two stimuli required for detection 50 percent of the time. We experience the difference threshold as a just noticeable difference (or jnd). conversion of one form of energy into another. In sensation, the transforming of stimulus energies, such as sights, sounds, and smells, into neural impulses our brain can interpret. the process of organizing and interpreting sensory information, enabling us to recognize meaningful objects and events. diminished sensitivity as a consequence of constant stimulation. the principle that, to be perceived as different, two stimuli must differ by a constant minimum percentage (rather than a constant amount). |

Experience the Testing Effect

Test yourself repeatedly throughout your studies. This will not only help you figure out what you know and don’t know; the testing itself will help you learn and remember the information more effectively thanks to the testing effect.

Question 6.1

1. Sensation is to ________ as perception is to ________.

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 6.2

2. The process by which we organize and interpret sensory information is called .

Question 6.3

3. Subliminal stimuli are

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 6.4

4. Another term for difference threshold is the .

Question 6.5

5. Weber's law states that for a difference to be perceived, two stimuli must differ by

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 6.6

6. Sensory adaptation helps us focus on

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 6.7

7. Our perceptual set influences what we perceive. This mental tendency reflects our

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Use  to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in

to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in  .

.