Light Energy and Eye Structures

6-

Our eyes receive light energy and transduce (transform) it into neural messages that our brain then processes into what we consciously see. How does such a taken-

The Stimulus Input: Light Energy

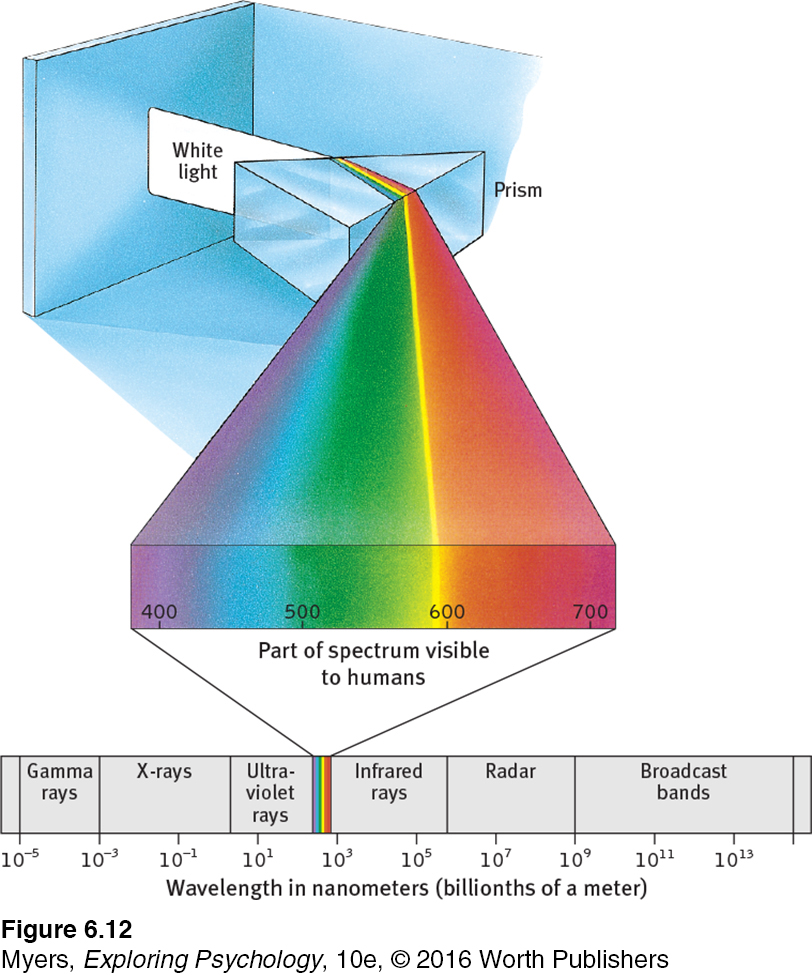

When you look at a bright red tulip, the stimuli striking your eyes are not particles of the color red but pulses of electromagnetic energy that your visual system perceives as red. What we see as visible light is but a thin slice of the whole spectrum of electromagnetic energy, ranging from imperceptibly short gamma waves to the long waves of radio transmission (FIGURE 6.12 below). Other organisms are sensitive to differing portions of the spectrum. Bees, for instance, cannot see what we perceive as red but can see ultraviolet light.

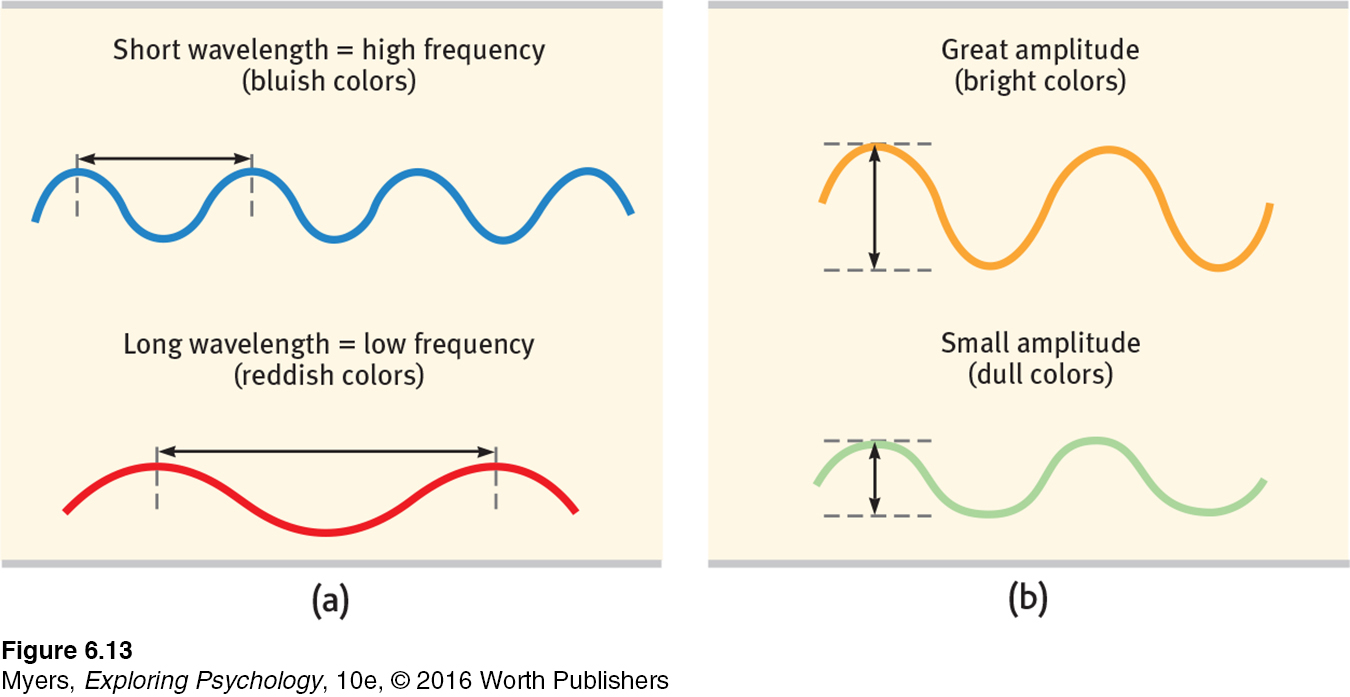

wavelength the distance from the peak of one light wave or sound wave to the peak of the next. Electromagnetic wavelengths vary from the short blips of cosmic rays to the long pulses of radio transmission.

hue the dimension of color that is determined by the wavelength of light; what we know as the color names blue, green, and so forth.

intensity the amount of energy in a light wave or sound wave, which influences what we perceive as brightness or loudness. Intensity is determined by the wave’s amplitude (height).

Two physical characteristics of light help determine our experience. Light’s wavelength—the distance from one wave peak to the next (FIGURE 6.13a below)—determines its hue (the color we experience, such as a tulip’s red petals or green leaves). Intensity—the amount of energy in light waves (determined by a wave’s amplitude, or height)—influences brightness (FIGURE 6.13b). To understand how we transform physical energy into color and meaning, consider the eye.

The Eye

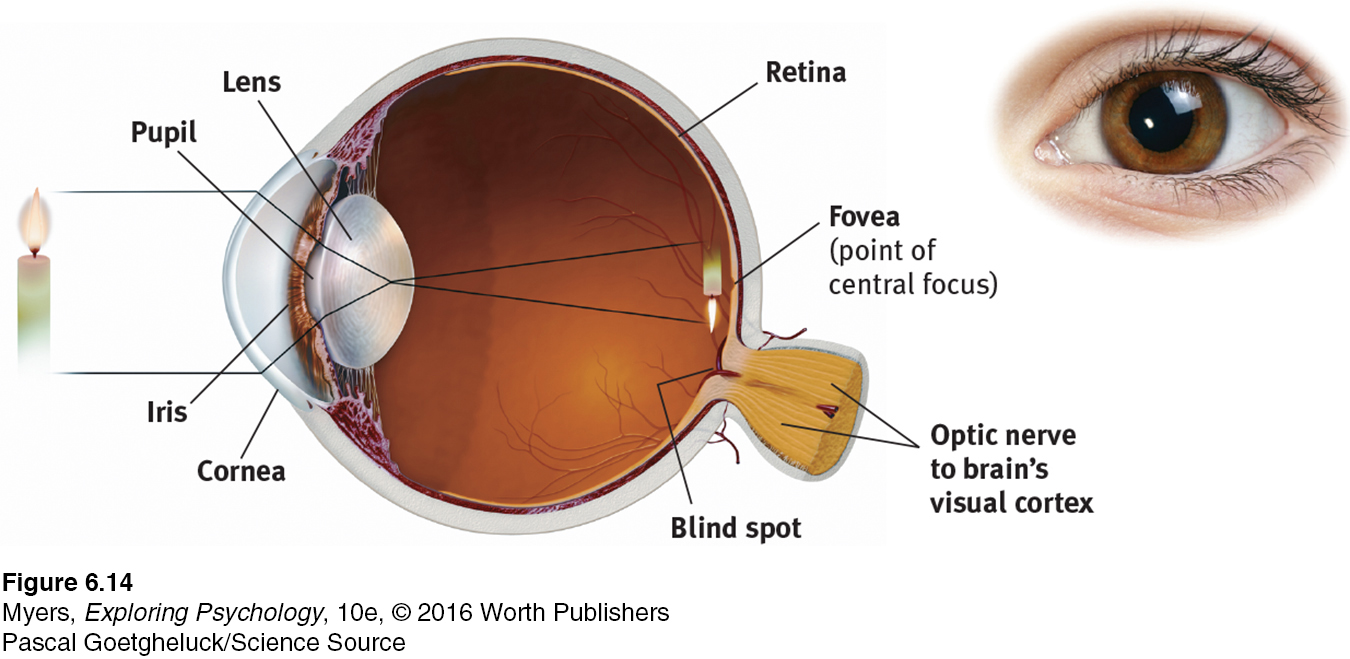

Light enters the eye through the cornea, which bends light to help provide focus (FIGURE 6.14 below). The light then passes through the pupil, a small adjustable opening surrounded by the iris, a colored muscle that controls the size of the pupil by dilating or constricting in response to light intensity—

retina the light-

accommodation the process by which the eye’s lens changes shape to focus near or far objects on the retina.

Behind the pupil is a transparent lens that focuses incoming light rays into an image on the retina, a multilayered tissue on the eyeball’s sensitive inner surface. The lens focuses the rays by changing its curvature and thickness, in a process called accommodation.

For centuries, scientists knew that when an image of a candle passes through a small opening, it casts an inverted mirror image on a dark wall behind. If the image passing through the pupil casts this sort of upside-

Information Processing in the Eye and Brain

Retinal Processing

6-

rods retinal receptors that detect black, white, and gray, and are sensitive to movement; necessary for peripheral and twilight vision, when cones don’t respond.

cones retinal receptors that are concentrated near the center of the retina and that function in daylight or in well-

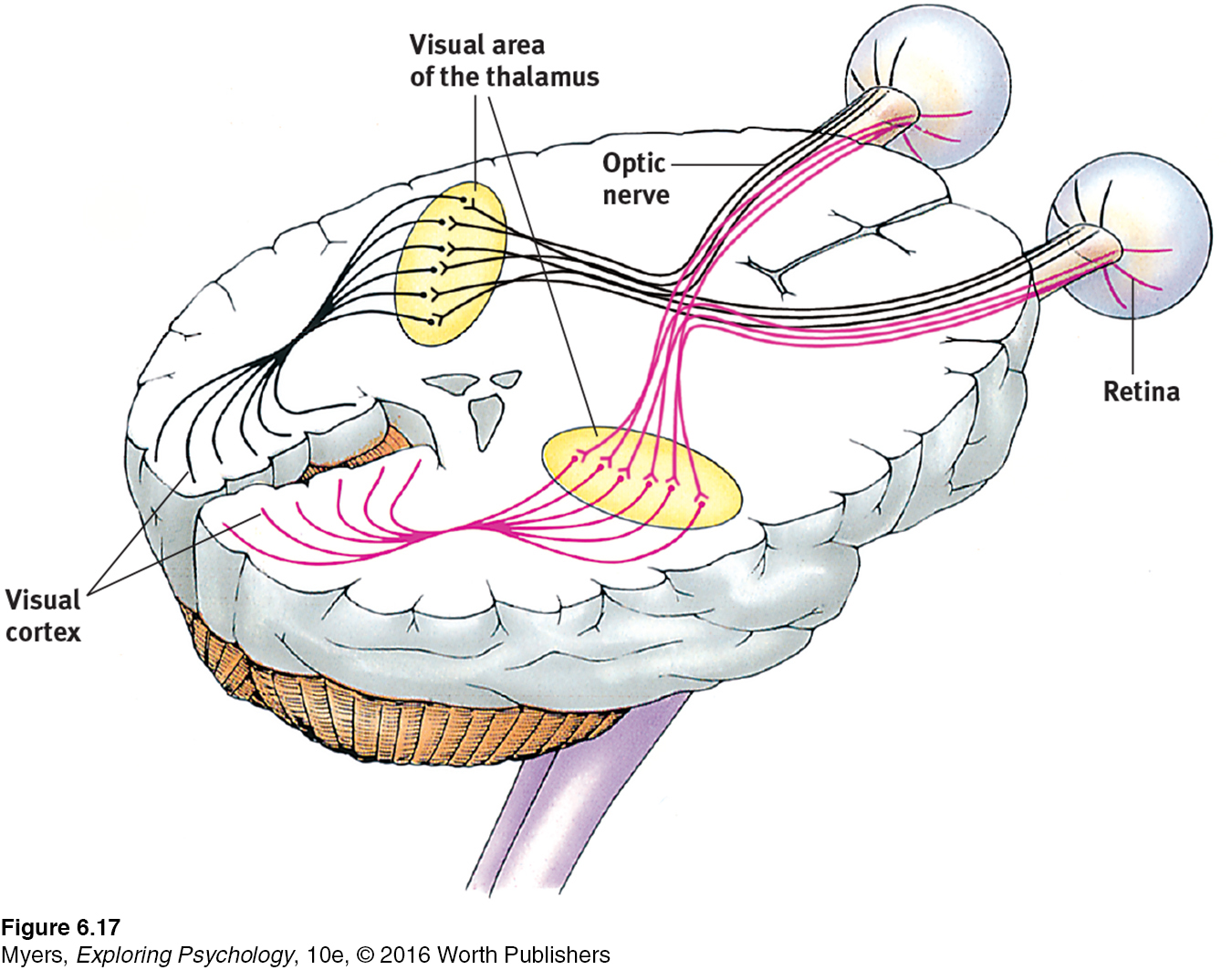

optic nerve the nerve that carries neural impulses from the eye to the brain.

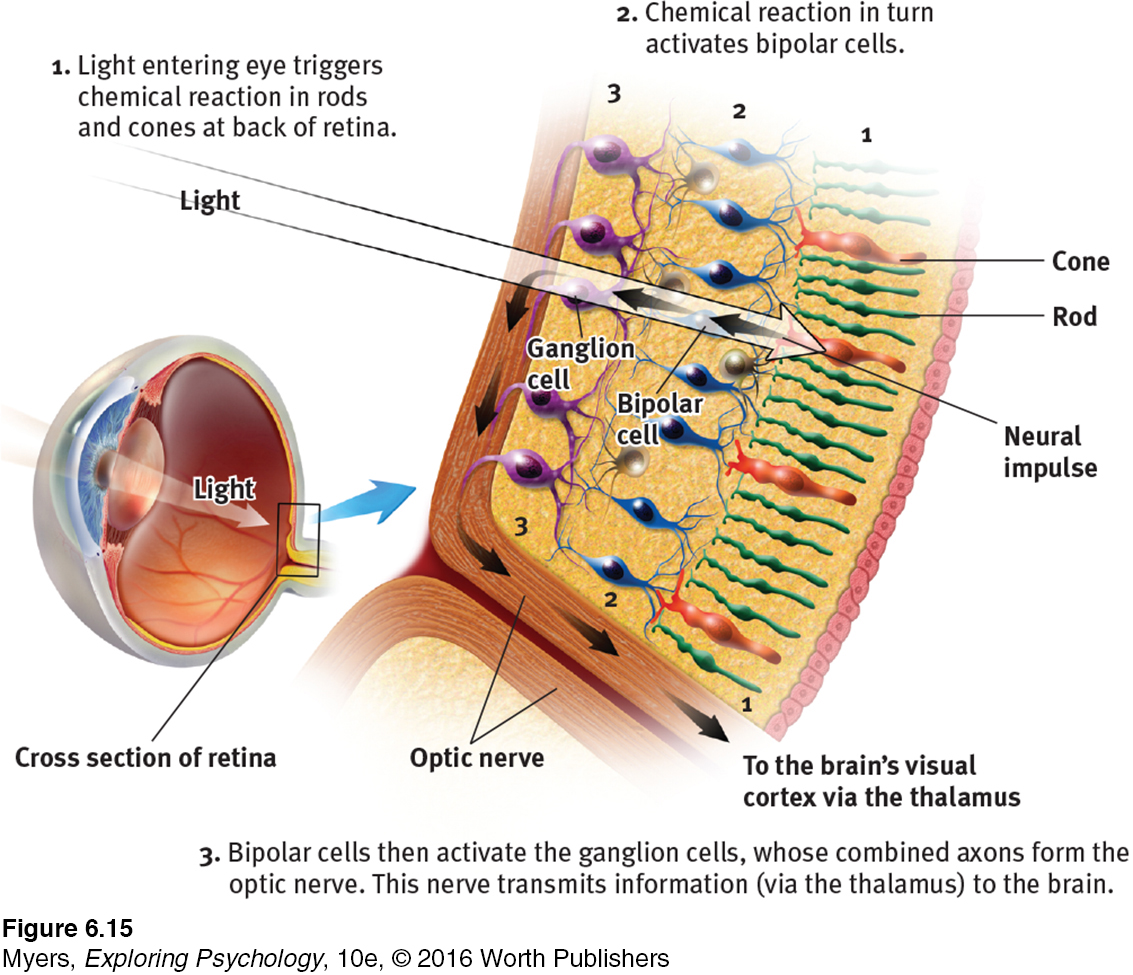

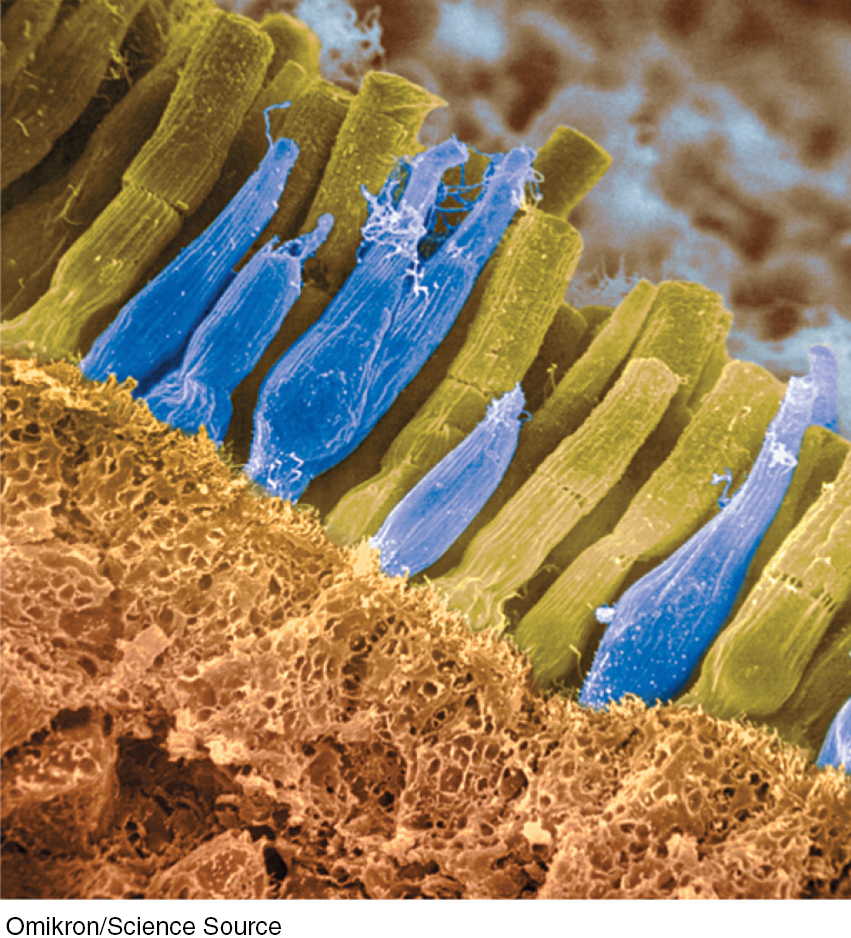

Imagine that you could follow behind a single light-

blind spot the point at which the optic nerve leaves the eye, creating a “blind” spot because no receptor cells are located there.

We pay a small price for this eye-

(Answer)

fovea the central focal point in the retina, around which the eye’s cones cluster.

Rods and cones differ in where they’re found and what they do (TABLE 6.1). Cones cluster in and around the fovea, the retina’s area of central focus (see FIGURE 6.14). Many cones have their own hotline to the brain, which devotes a large area to input from the fovea. These direct connections preserve the cones’ precise information, making them better able to detect fine detail.

Receptors in the Human Eye: Rod-

| Cones | Rods | |

|---|---|---|

| Number | 6 million | 120 million |

| Location in retina | Center | Periphery |

| Sensitivity in dim light | Low | High |

| Color sensitivity | High | Low |

| Detail sensitivity | High | Low |

Rods don’t have dedicated hotlines. Rods share bipolar cells, which send combined messages. To experience this rod-

Cones also enable you to perceive color. In dim light they become ineffectual, so you see no colors. Rods, which enable black-

When you enter a darkened theater or turn off the light at night, your eyes adapt. Your pupils dilate to allow more light to reach your retina, but it typically takes 20 minutes or more before your eyes fully adapt. You can demonstrate dark adaptation by closing or covering one eye for 20 minutes. Then make the light in the room not quite bright enough to read this book with your open eye. Now open the dark-

At the entry level, the retina’s neural layers don’t just pass along electrical impulses; they also help to encode and analyze sensory information. (The third neural layer in a frog’s eye, for example, contains the “bug detector” cells that fire only in response to moving fly-

The same sensitivity that enables retinal cells to fire messages can lead them to misfire, as you can demonstrate. Turn your eyes to the left, close them, and then gently rub the right side of your right eyelid with your fingertip. Note the patch of light to the left, moving as your finger moves.

Why do you see light? Why at the left? This happens because your retinal cells are so responsive that even pressure triggers them. But your brain interprets their firing as light. Moreover, it interprets the light as coming from the left—

RETRIEVE IT

Question

Some nocturnal animals, such as toads, mice, rats, and bats, have impressive night vision thanks to having many more (rods/cones) than (rods/cones) in their retinas. These creatures probably have very poor (color/black-and-white) vision.

Question

Cats are able to open their much wider than we can, which allows more light into their eyes so they can see better at night.

Color Processing

6-9 How do we perceive color in the world around us?

One of vision’s most basic and intriguing mysteries is how we see the world in color. In everyday conversation, we talk as though objects possess color: “A tomato is red.” Recall the old question, “If a tree falls in the forest and no one hears it, does it make a sound?” We can ask the same of color: If no one sees the tomato, is it red?

The answer is No. First, the tomato is everything but red, because it rejects (reflects) the long wavelengths of red. Second, the tomato’s color is our mental construction. As Isaac Newton (1704) noted, “The [light] rays are not colored.” Like all aspects of vision, our perception of color resides not in the object but in the theater of our brains, as evidenced by our dreaming in color.

“Only mind has sight and hearing; all things else are deaf and blind.”

Epicharmus, Fragments, 550 B.C.E.

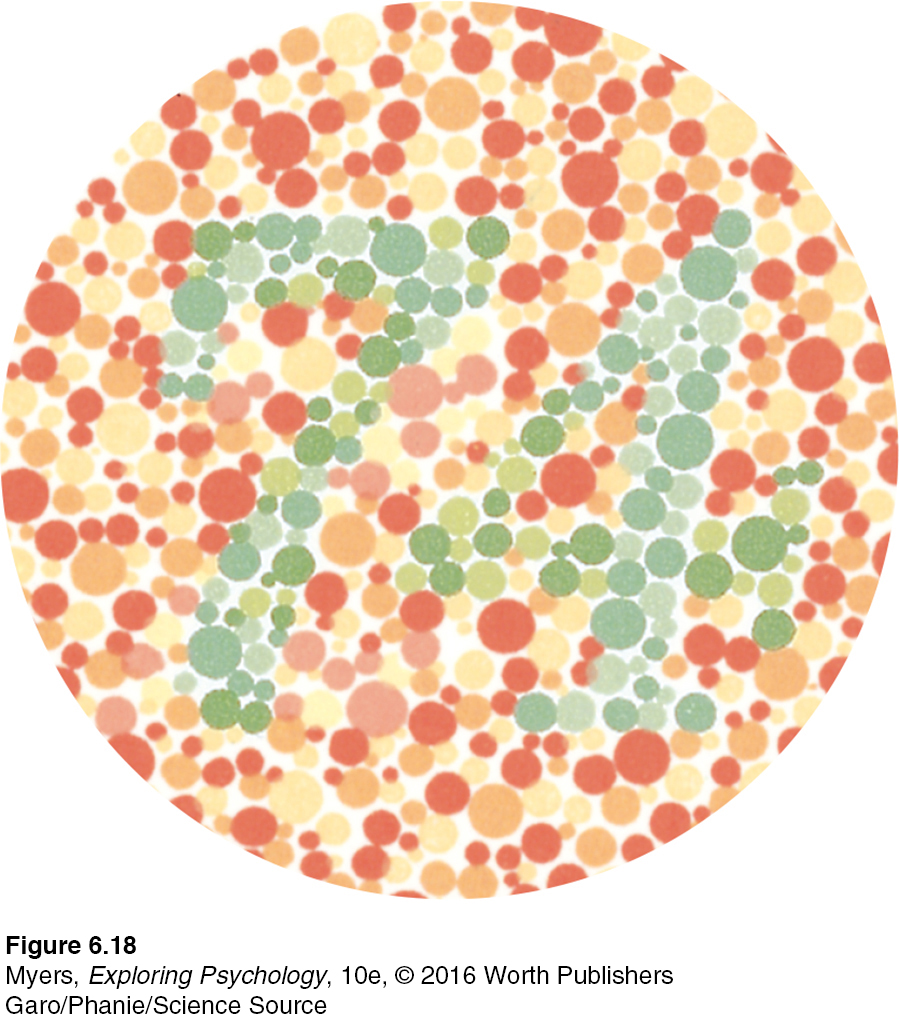

How, from the light energy striking the retina, does our brain construct our experience of color—

Young-

Modern detective work on the mystery of color vision began in the nineteenth century, when Hermann von Helmholtz built on the insights of an English physicist, Thomas Young. Any color can be created by combinations of different amounts of light waves of three primary colors—

Most people with color-

But why do people blind to red and green often still see yellow? And why does yellow appear to be a pure color and not a mixture of red and green, the way purple is of red and blue? As Ewald Hering soon noted, trichromatic theory leaves some parts of the color vision mystery unsolved.

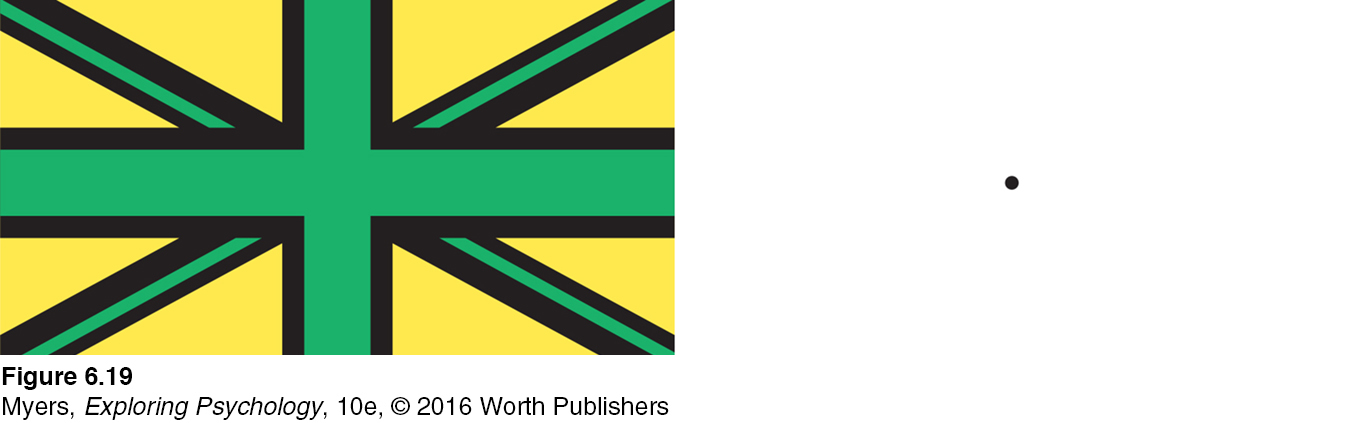

Hering, a physiologist, had found a clue in afterimages. Stare at a green square for a while and then look at a white sheet of paper, and you will see red, green’s opponent color. Stare at a yellow square and its opponent color, blue, will appear on the white paper. (To experience this, try the flag demonstration in FIGURE 6.19.) Hering formed another hypothesis: There must be two additional color processes, one responsible for red-

opponent-process theory the theory that opposing retinal processes (red-

Indeed, a century later, researchers also confirmed Hering’s opponent-process theory. Three sets of opponent retinal processes—

How then do we explain afterimages, such as in the flag demonstration? By staring at green, we tire our green response. When we then stare at white (which contains all colors, including red), only the red part of the green-

For an interactive review and demonstration of these color vision principles, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Colorful World.

For an interactive review and demonstration of these color vision principles, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Colorful World.

The present solution to the mystery of color vision is therefore roughly this: Color processing occurs in two stages. The retina’s red, green, and blue cones respond in varying degrees to different color stimuli, as the Young-

RETRIEVE IT

Question

What are two key theories of color vision? Are they contradictory or complementary? Explain.

Feature Detection

6-

feature detectors nerve cells in the brain that respond to specific features of the stimulus, such as shape, angle, or movement.

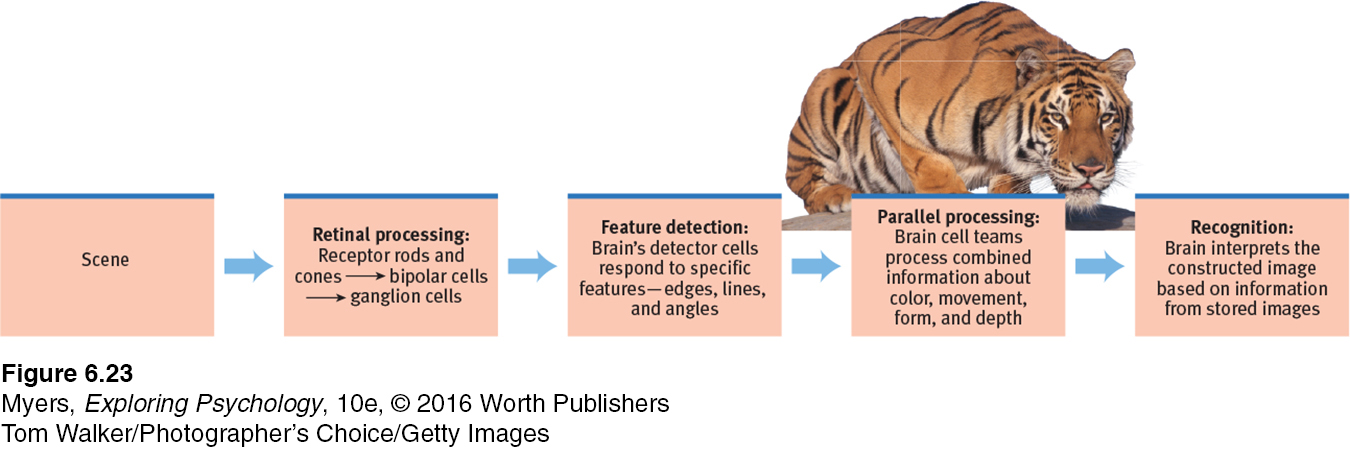

Scientists once likened the brain to a movie screen, on which the eye projected images. But then along came David Hubel and Torsten Wiesel (1979), who showed that our brain’s computing system deconstructs visual images and then reassembles them. Hubel and Wiesel received a Nobel Prize for their work on feature detectors, nerve cells in the brain that respond to a scene’s specific visual features—

Using microelectrodes, they had discovered that some neurons fired actively when cats were shown lines at one angle, while other neurons responded to lines at a different angle. They surmised that these specialized neurons in the occipital lobe’s visual cortex, now known as feature detectors, receive information from individual ganglion cells in the retina. Feature detectors pass this specific information to other cortical areas, where teams of cells (supercell clusters) respond to more complex patterns.

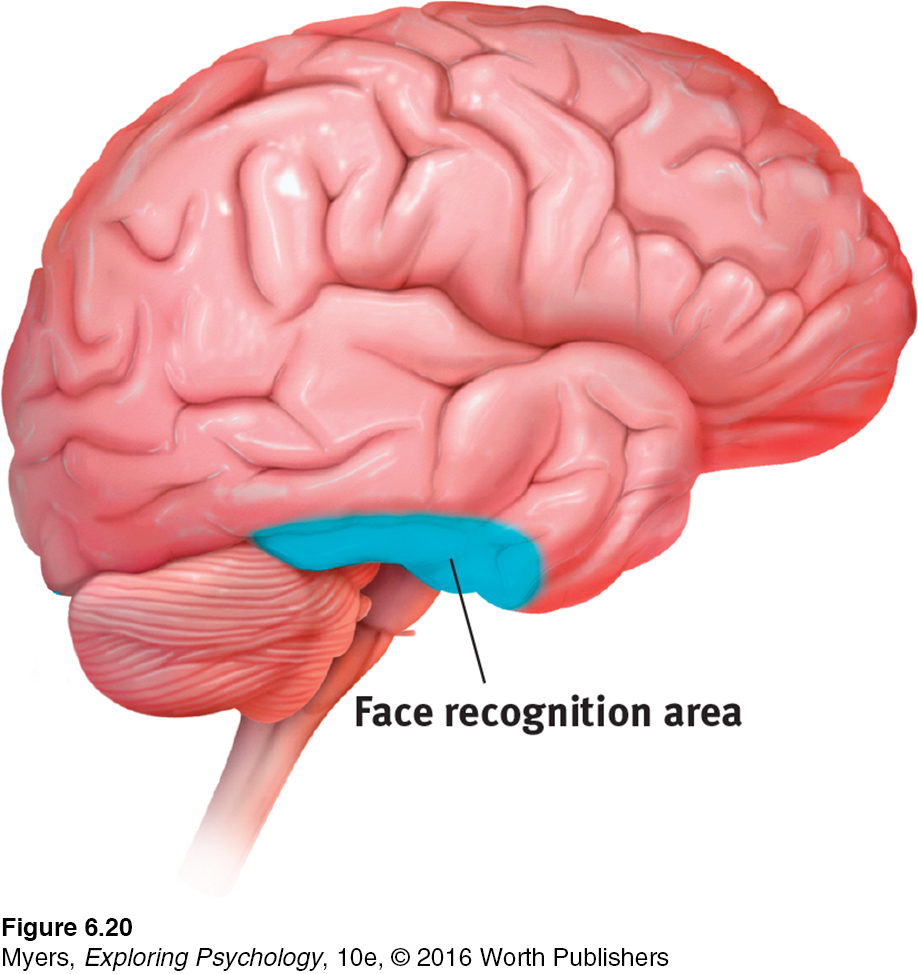

For biologically important objects and events, monkey brains (and surely ours as well) have a “vast visual encyclopedia” distributed as specialized cells (Perrett et al., 1988, 1992, 1994). These cells respond to one type of stimulus, such as a specific gaze, head angle, posture, or body movement. Other supercell clusters integrate this information and fire only when the cues collectively indicate the direction of someone’s attention and approach. This instant analysis, which aided our ancestors’ survival, also helps a soccer player anticipate where to strike the ball, and a driver anticipate a pedestrian’s next movement. One temporal lobe area by your right ear (FIGURE 6.20) enables you to perceive faces and, thanks to a specialized neural network, to recognize them from varied viewpoints (Connor, 2010). If stimulated in this area, you might spontaneously see faces. If this region were damaged, you might recognize other forms and objects, but not familiar faces.

Researchers can temporarily disrupt the brain’s face-

Parallel Processing

6-

parallel processing the processing of many aspects of a problem simultaneously; the brain’s natural mode of information processing for many functions, including vision.

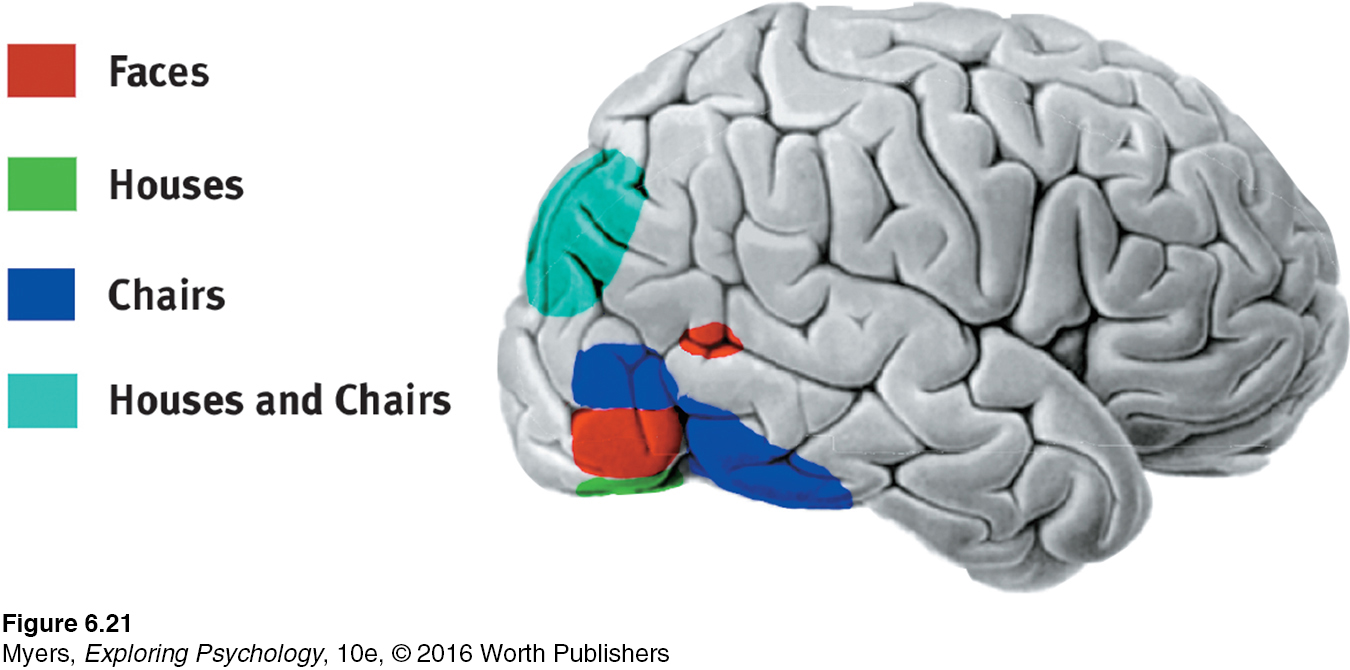

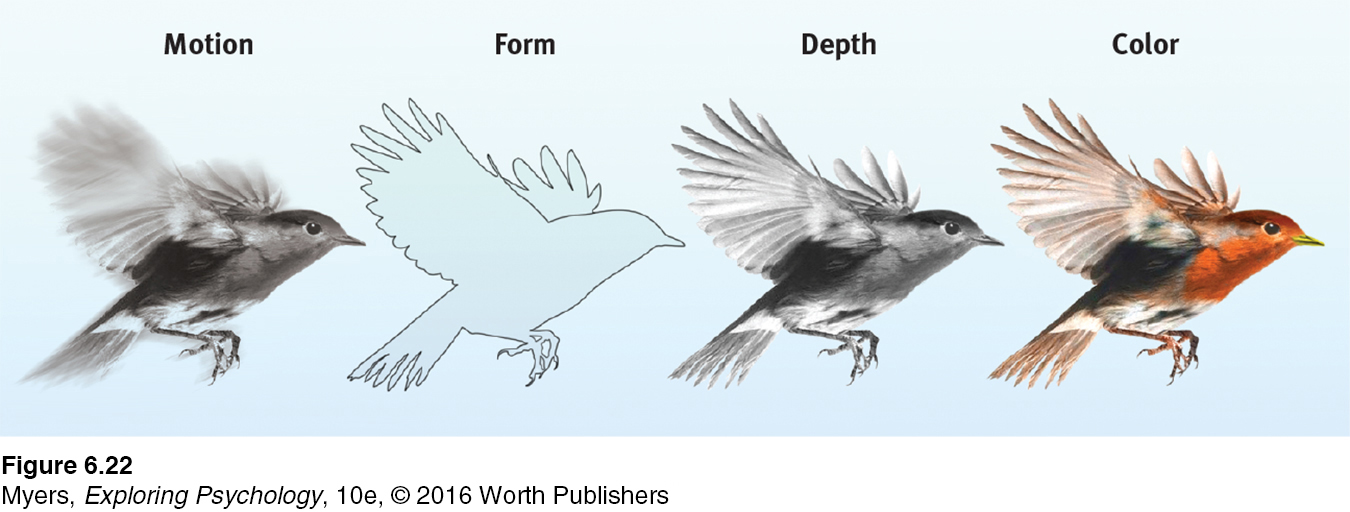

Our brain achieves these and other remarkable feats by parallel processing: doing many things at once. To analyze a visual scene, the brain divides it into subdimensions—

For a 4-

For a 4-

To recognize a face, your brain integrates information projected by your retinas to several visual cortex areas, compares it with stored information, and enables you to recognize the face: Grandmother! Scientists have debated whether this stored information is contained in a single cell or distributed over a vast network of cells. Some supercells—

Destroy or disable a neural workstation for a visual subtask, and something peculiar results, as happened to “Mrs. M.” (Hoffman, 1998). After a stroke damaged areas near the rear of both sides of her brain, she found herself unable to perceive movement. People in a room seemed “suddenly here or there but I [did not see] them moving.” Pouring tea into a cup became a challenge because the fluid appeared frozen—

After stroke or surgery has damaged the brain’s visual cortex, others have experienced blindsight. Shown a series of sticks, they report seeing nothing. Yet when asked to guess whether the sticks are vertical or horizontal, their visual intuition typically offers the correct response. When told, “You got them all right,” they are astounded. There is, it seems, a second “mind”—a parallel processing system—

* * *

Think about the wonders of visual processing. As you read this page, the letters are transmitted by reflected light rays onto your retina, which triggers a process that sends formless nerve impulses to several areas of your brain, which integrates the information and decodes meaning, thus completing the transfer of information across time and space from our minds to your mind (FIGURE 6.23). That all of this happens instantly, effortlessly, and continuously is indeed awesome. As Roger Sperry (1985) observed, the “insights of science give added, not lessened, reasons for awe, respect, and reverence.”

“I am … wonderfully made.”

King David, Psalm 139:14

RETRIEVE IT

Question

What is the rapid sequence of events that occurs when you see and recognize a friend?

Perceptual Organization

6-

It’s one thing to understand how we see colors and shapes. But how do we organize and interpret those sights so that they become meaningful perceptions—

gestalt an organized whole. Gestalt psychologists emphasized our tendency to integrate pieces of information into meaningful wholes.

Early in the twentieth century, a group of German psychologists noticed that when given a cluster of sensations, people tend to organize them into a gestalt, a German word meaning a “form” or a “whole.” As we look straight ahead, we cannot separate the perceived scene into our left and right fields of view. It is, at every moment, one whole, seamless scene. Our conscious perception is an integrated whole.

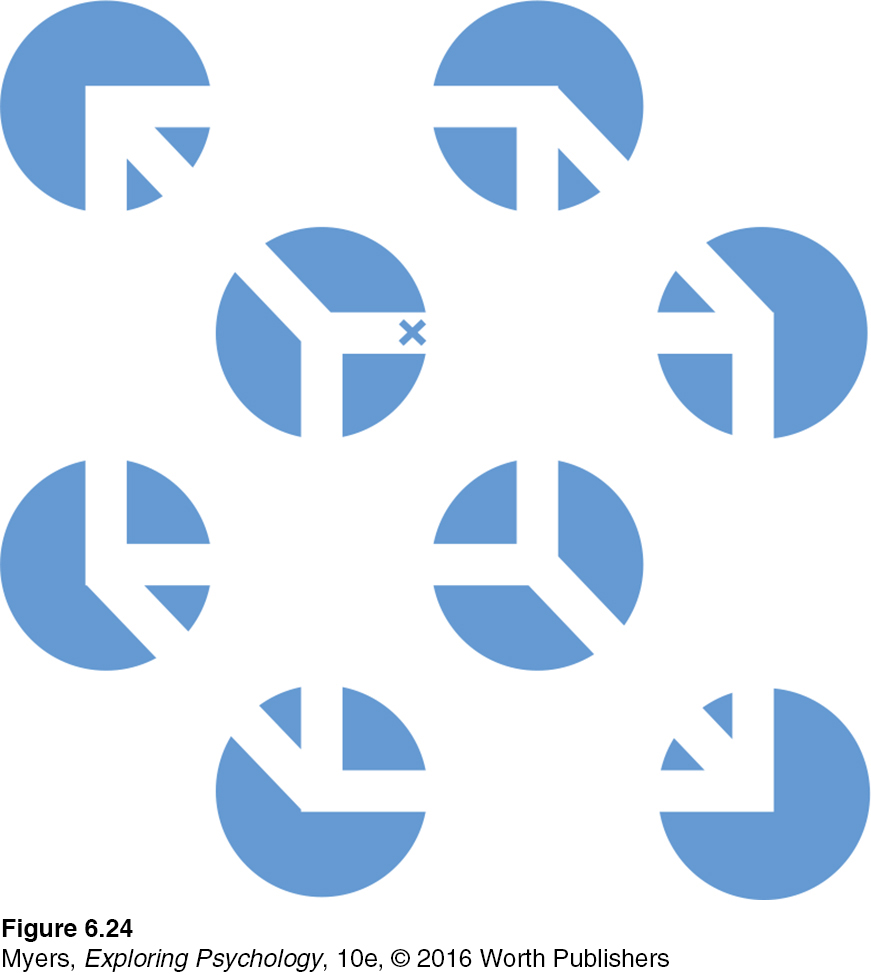

Consider FIGURE 6.24. Note that the individual elements of this figure, called a Necker cube, are really nothing but eight blue circles, each containing three converging white lines. When we view these elements all together, however, we see a cube that sometimes reverses direction. This phenomenon nicely illustrates a favorite saying of Gestalt psychologists: In perception, the whole may exceed the sum of its parts.

Over the years, the Gestalt psychologists demonstrated many principles we use to organize our sensations into perceptions (Wagemans et al., 2012a, b). Underlying all of them is a fundamental truth: Our brain does more than register information about the world. Perception is not just opening a shutter and letting a picture print itself on the brain. We filter incoming information and construct perceptions. Mind matters.

Form Perception

Imagine designing a video-

figure-ground the organization of the visual field into objects (the figures) that stand out from their surroundings (the ground).

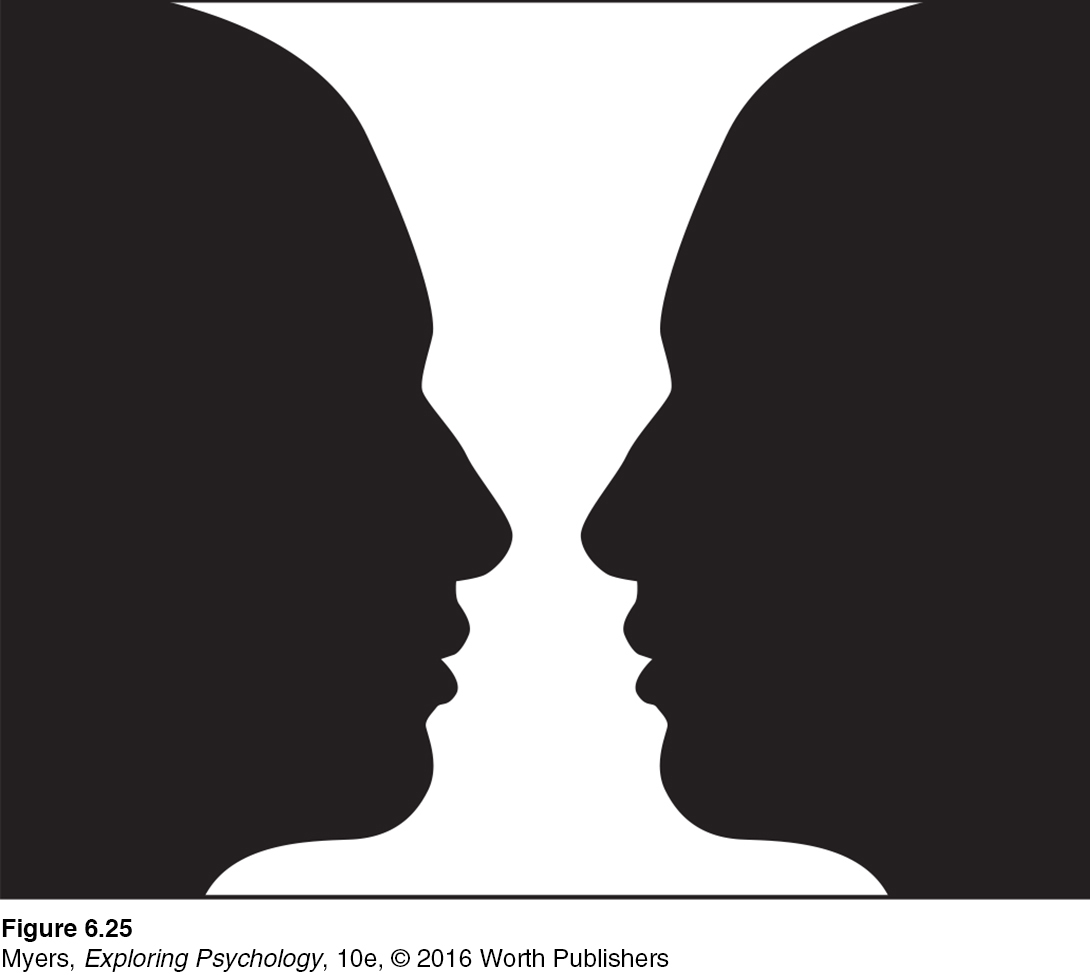

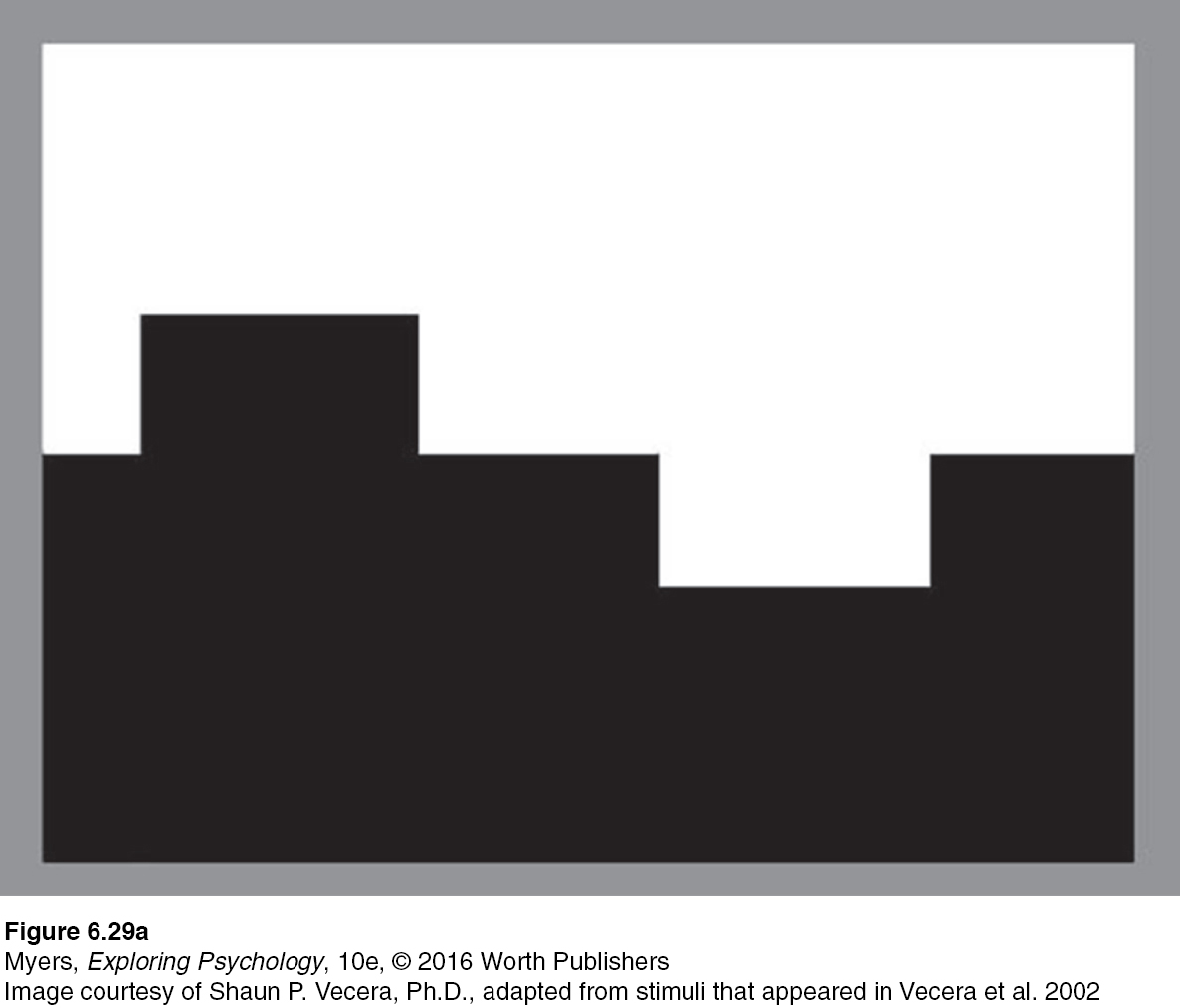

FIGURE AND GROUND To start with, the system would need to separate faces from their backgrounds. Likewise, in our eye-

grouping the perceptual tendency to organize stimuli into coherent groups.

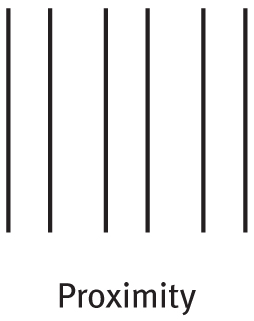

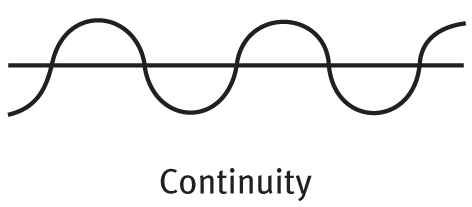

GROUPING Having discriminated figure from ground, we (and our video-

Proximity We group nearby figures together. We see not six separate lines, but three sets of two lines.

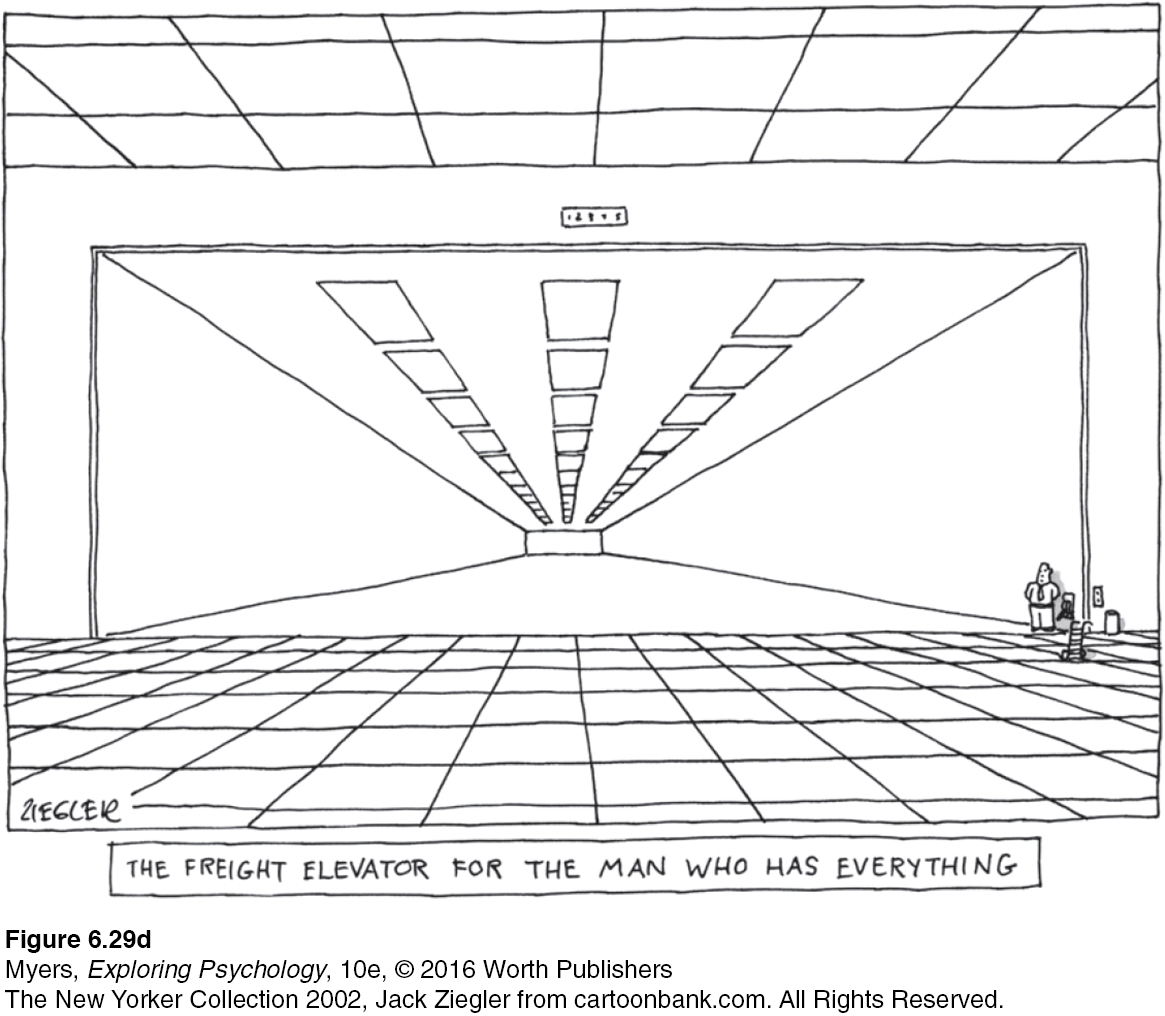

Continuity We perceive smooth, continuous patterns rather than discontinuous ones. This pattern could be a series of alternating semicircles, but we perceive it as two continuous lines—

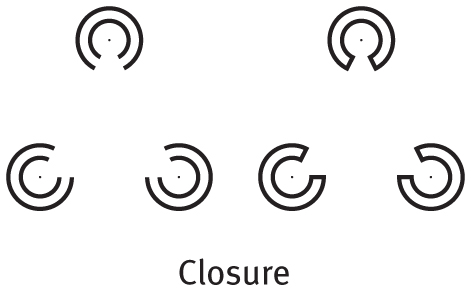

Closure We fill in gaps to create a complete, whole object. Thus we assume that the circles on the left are complete but partially blocked by the (illusory) triangle. Add nothing more than little line segments to close off the circles and your brain stops constructing a triangle.

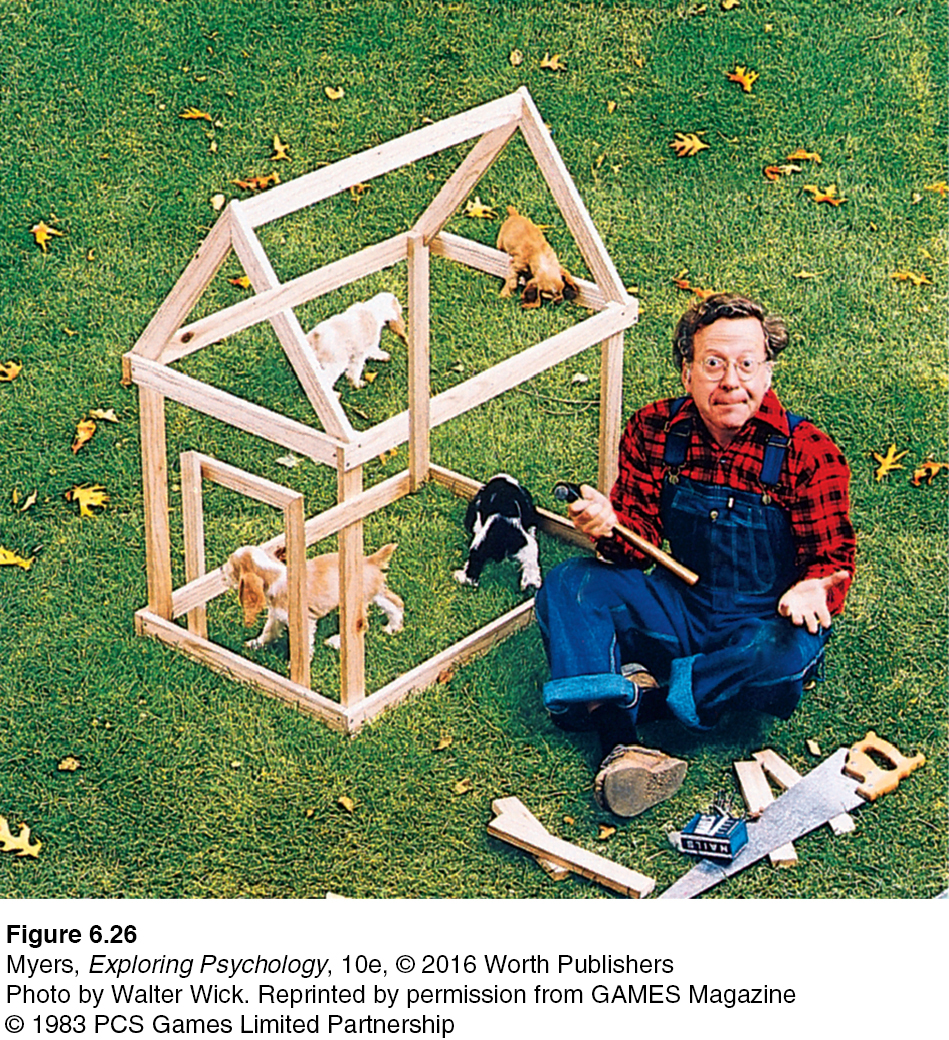

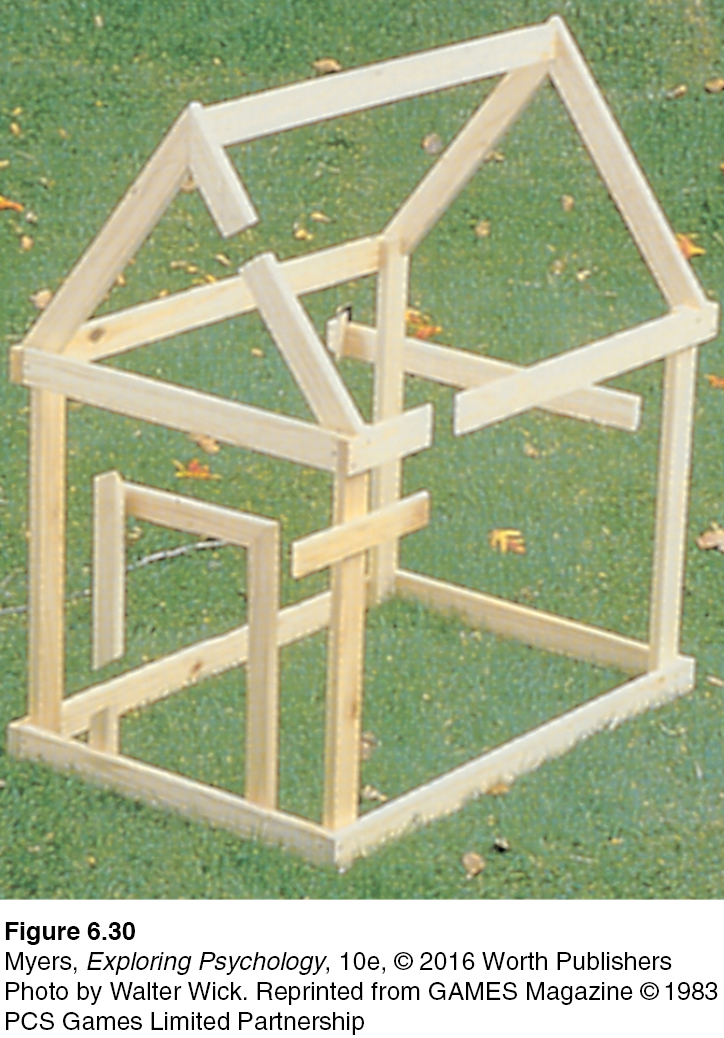

Such principles usually help us construct reality. Sometimes, however, they lead us astray, as when we look at the doghouse in FIGURE 6.26.

RETRIEVE IT

Question

In terms of perception, a band's lead singer would be considered (figure/ground), and the other musicians would be considered (figure/ground).

Question

What do we mean when we say that, in perception, the whole may exceed the sum of its parts?

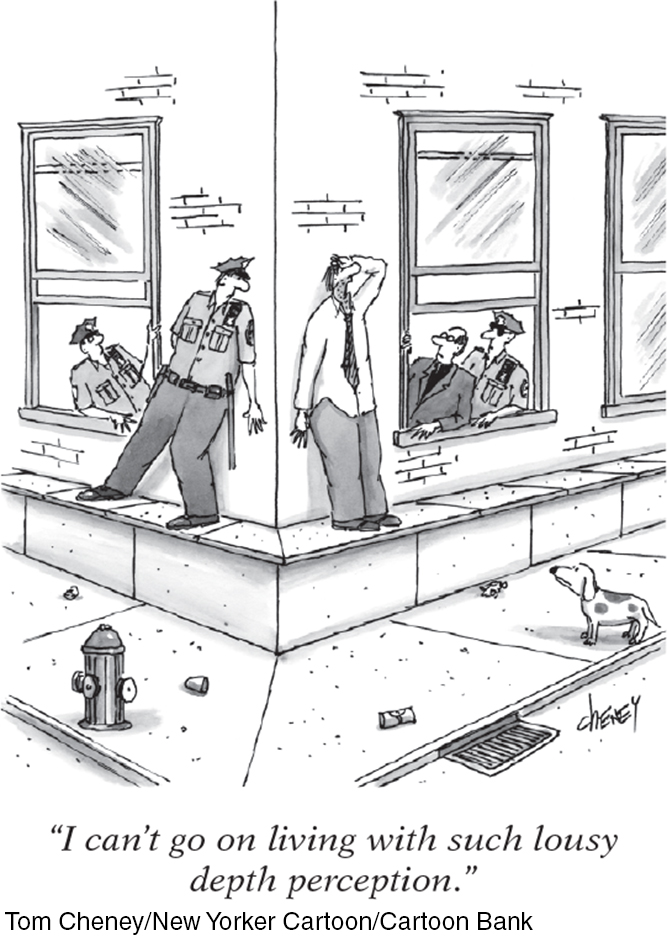

Depth Perception

6-13 How do we use binocular and monocular cues to perceive the world in three dimensions?

depth perception the ability to see objects in three dimensions although the images that strike the retina are two-dimensional; allows us to judge distance.

visual cliff a laboratory device for testing depth perception in infants and young animals.

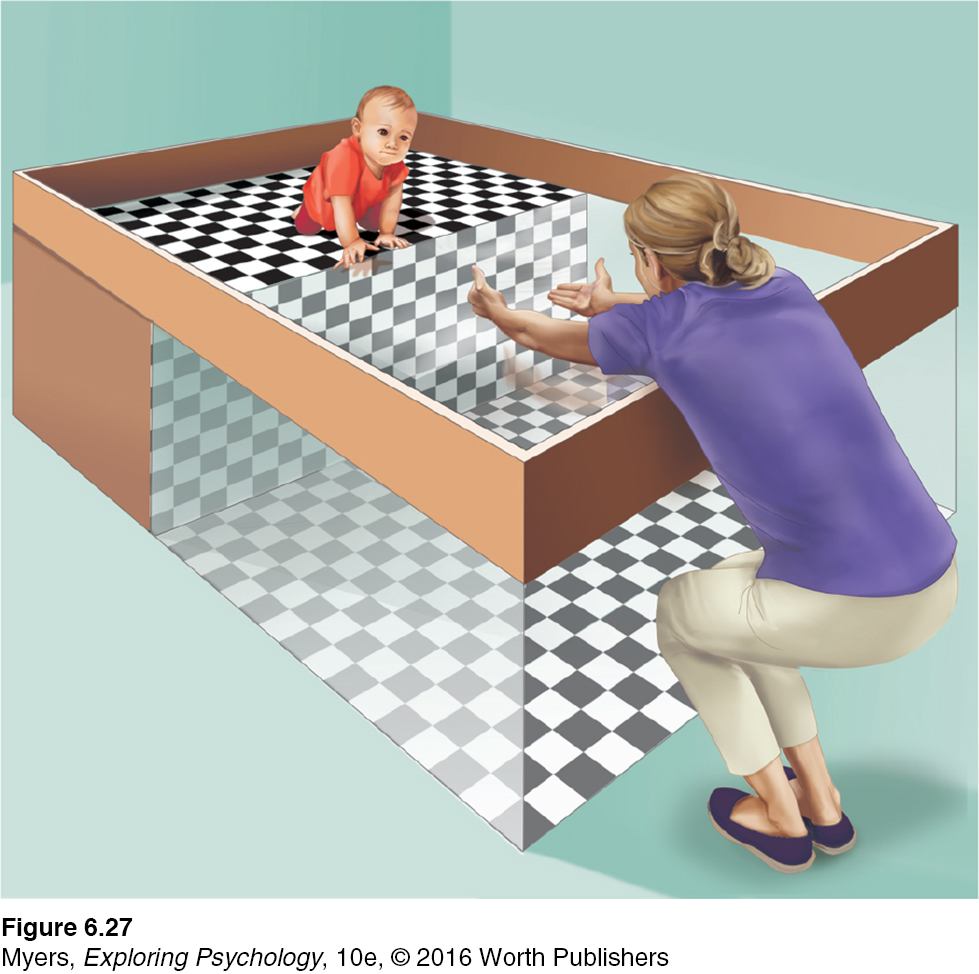

From the two-

Back in their Cornell University laboratory, Gibson and Walk placed 6-

Had they learned to perceive depth? Mobile, newborn animals, such as kittens, come prepared to see depth—

How do we do it? How do we transform two differing two-

binocular cues depth cues, such as retinal disparity, that depend on the use of two eyes.

BINOCULAR CUES Try this: With both eyes open, hold two pens or pencils in front of you and touch their tips together. Now do so with one eye closed. With one eye, the task becomes noticeably more difficult, demonstrating the importance of binocular cues in judging the distance of nearby objects. Two eyes are better than one.

retinal disparity a binocular cue for perceiving depth: By comparing images from the retinas in the two eyes, the brain computes distance—

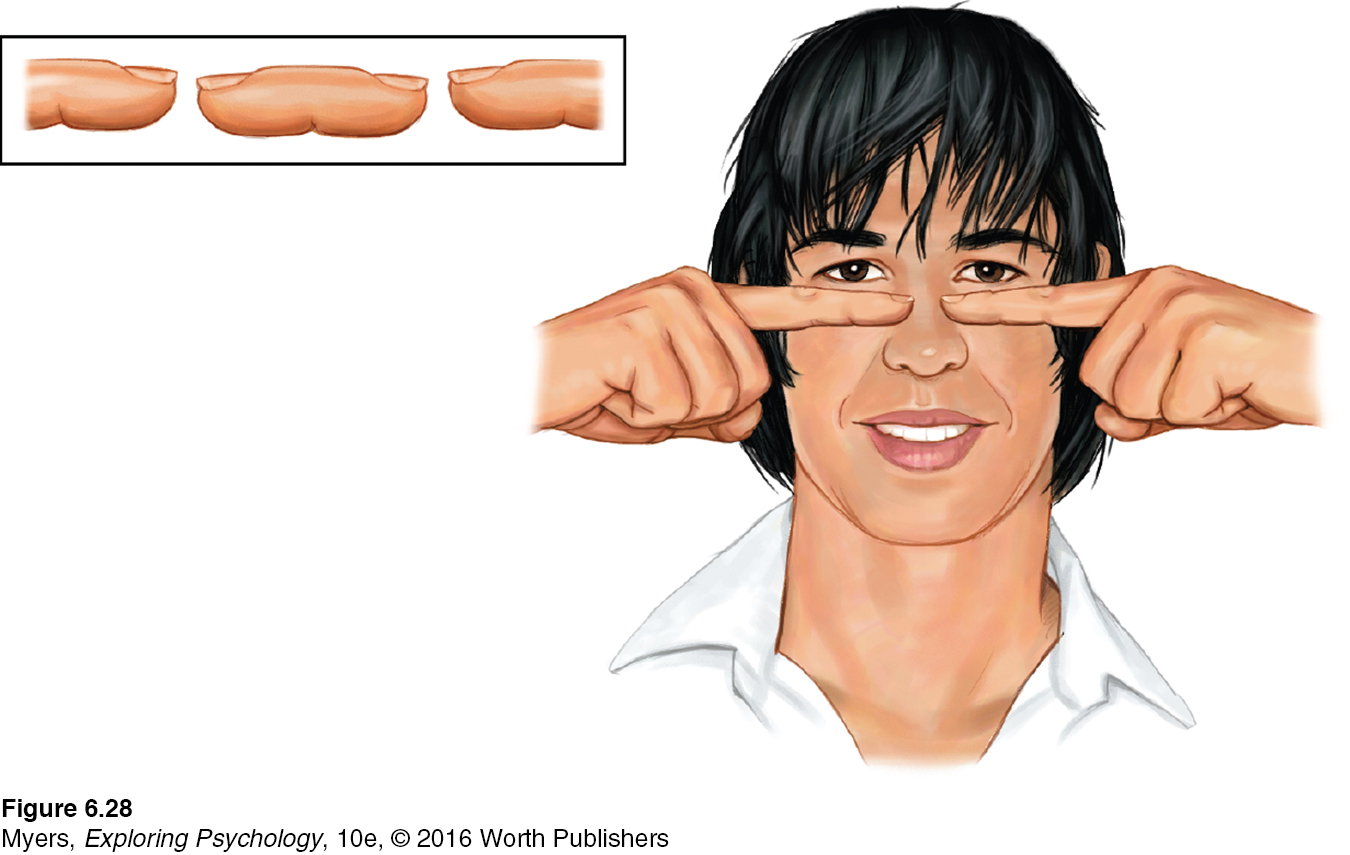

Because your eyes are about 2½ inches apart, your retinas receive slightly different images of the world. By comparing these two images, your brain can judge how close an object is to you. The greater the retinal disparity, or difference between the two images, the closer the object. Try it. Hold your two index fingers, with the tips about half an inch apart, directly in front of your nose, and your retinas will receive quite different views. If you close one eye and then the other, you can see the difference. (Bring your fingers close and you can create a finger sausage, as in FIGURE 6.28.) At a greater distance—

We could easily build this feature into our video-

monocular cues depth cues, such as interposition and linear perspective, available to either eye alone.

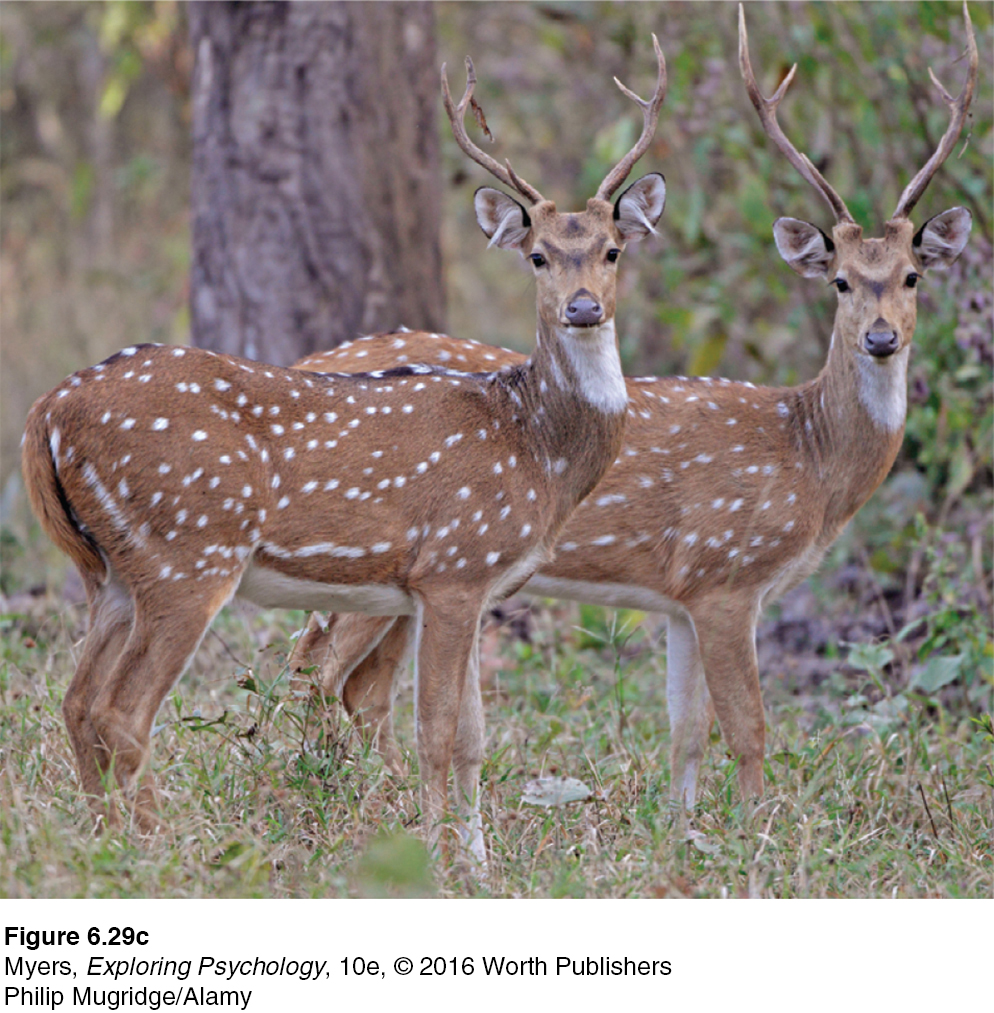

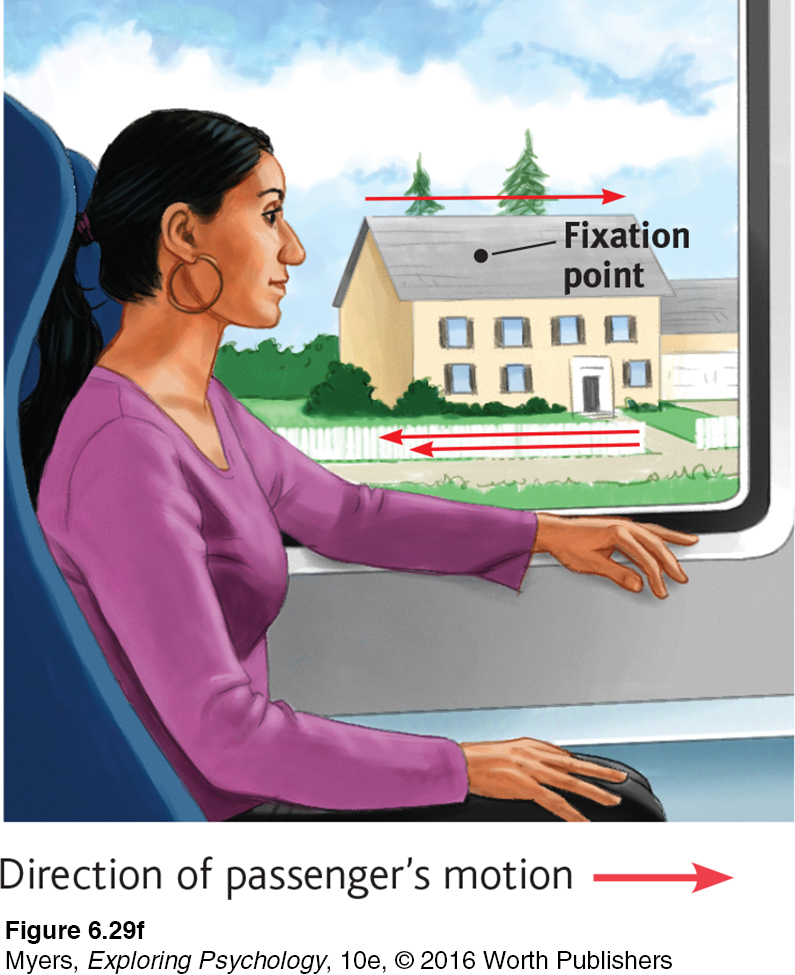

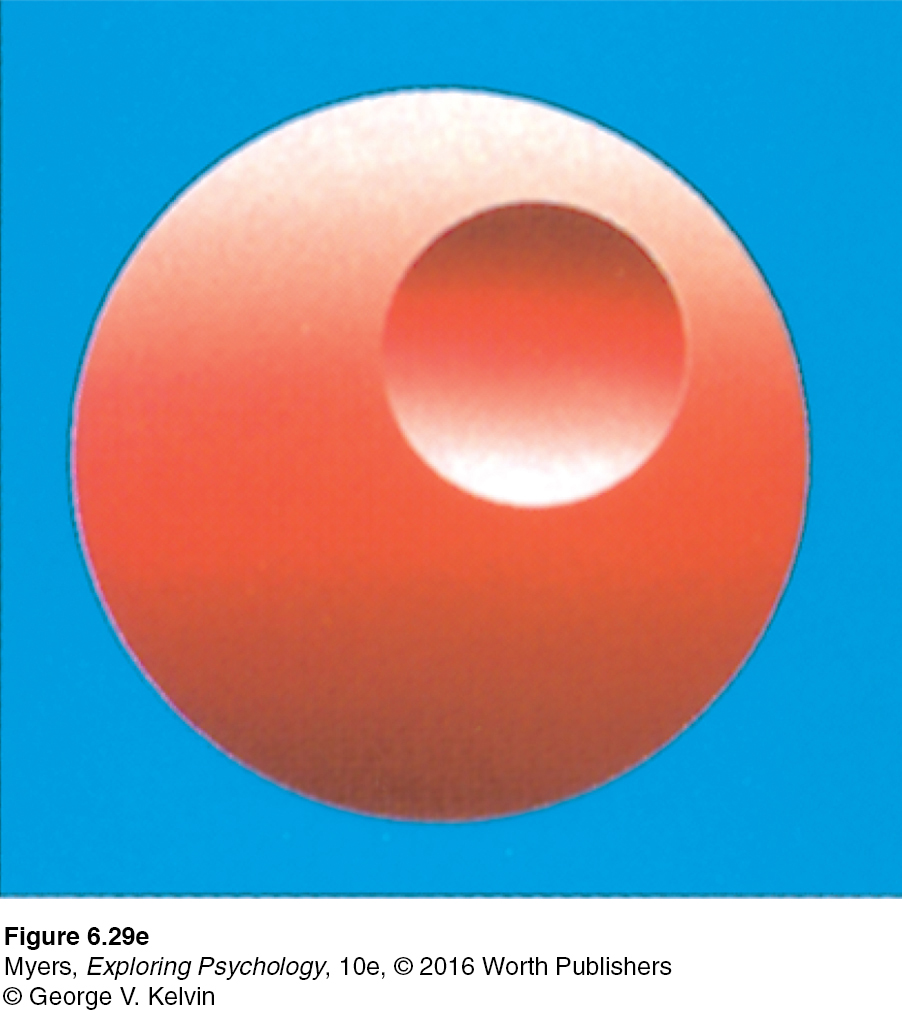

MONOCULAR CUES How do we judge whether a person is 10 or 100 meters away? Retinal disparity won’t help us here, because there won’t be much difference between the images cast on our right and left retinas. At such distances, we depend on monocular cues (depth cues available to each eye separately). See FIGURE 6.29a, b, c, d, e, and f for some examples.

For animated demonstrations and explanations of these cues, visit LaunchPad’s Concept Practice: Depth Cues.

For animated demonstrations and explanations of these cues, visit LaunchPad’s Concept Practice: Depth Cues.

RETRIEVE IT

Question

How do we normally perceive depth?

Perceptual Constancy

6-

perceptual constancy perceiving objects as unchanging (having consistent color, brightness, shape, and size) even as illumination and retinal images change.

So far, we have noted that our video-

color constancy perceiving familiar objects as having consistent color, even if changing illumination alters the wavelengths reflected by the objects.

COLOR AND BRIGHTNESS CONSTANCIES Our experience of color depends on an object’s context. This would be clear if you viewed an isolated tomato through a paper tube over the course of a day. The tomato’s color would seem to change as the light—

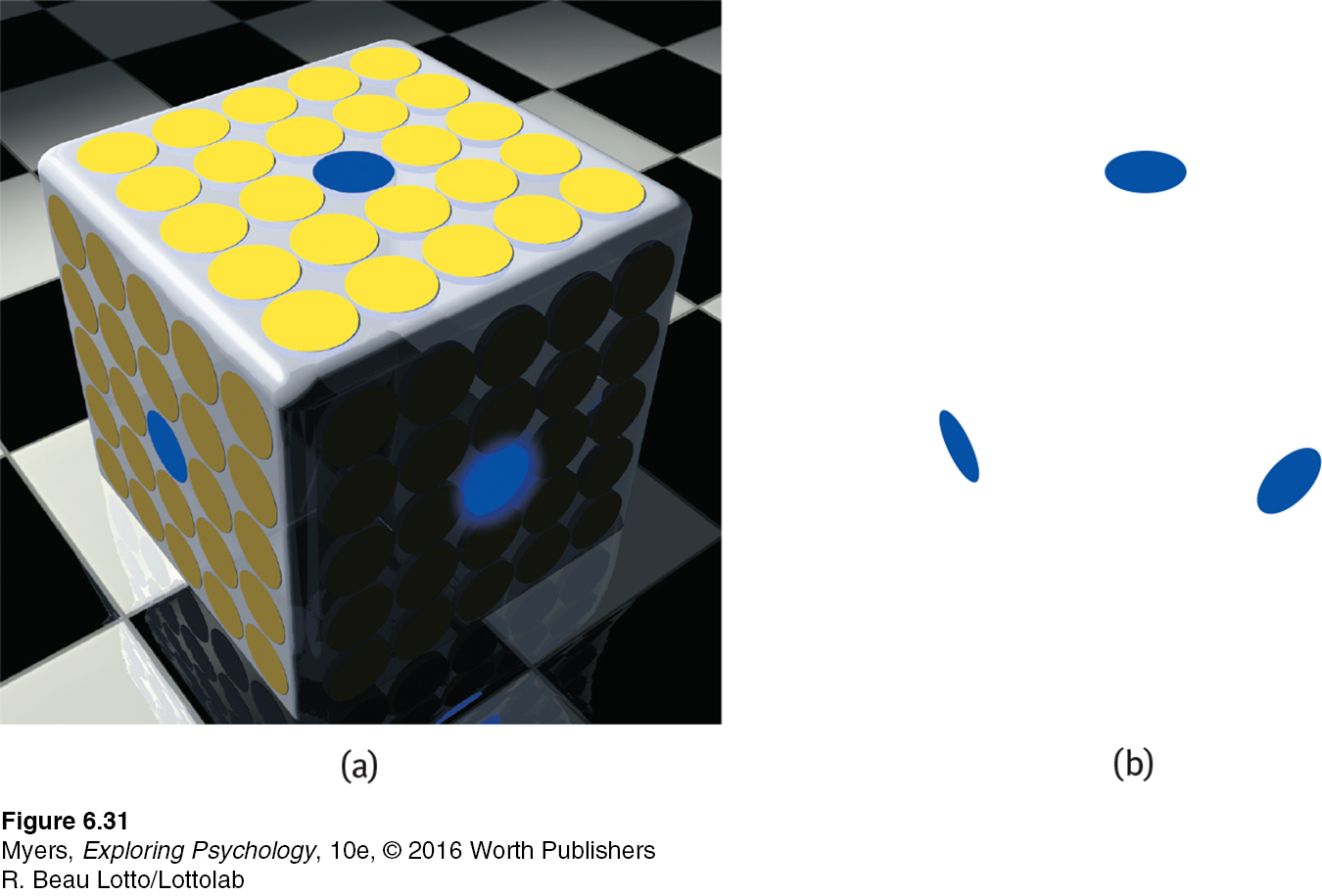

Though we take color constancy for granted, this ability is truly remarkable. A blue poker chip under indoor lighting reflects wavelengths that match those reflected by a sunlit gold chip (Jameson, 1985). Yet bring a goldfinch indoors and it won’t look like a bluebird. The color is not in the bird’s feathers. We see color thanks to our brain’s computations of the light reflected by an object relative to the objects surrounding it. FIGURE 6.31 dramatically illustrates the ability of a blue object to appear very different in three different contexts. Yet we have no trouble seeing these disks as blue. Nor does knowing the truth—

“From there to here, from here to there, funny things are everywhere.”

Dr. Seuss, One Fish, Two Fish, Red Fish, Blue Fish, 1960

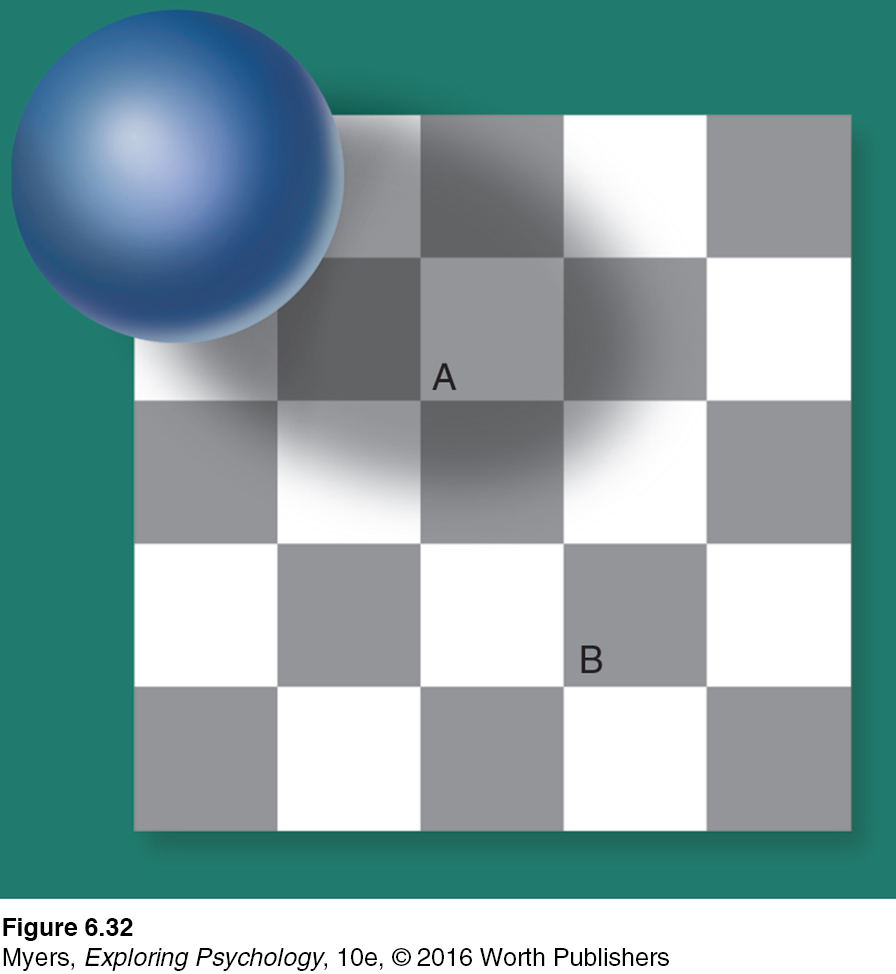

Brightness constancy (also called lightness constancy) similarly depends on context. We perceive an object as having a constant brightness even as its illumination varies. This perception of constancy depends on relative luminance—

This principle—

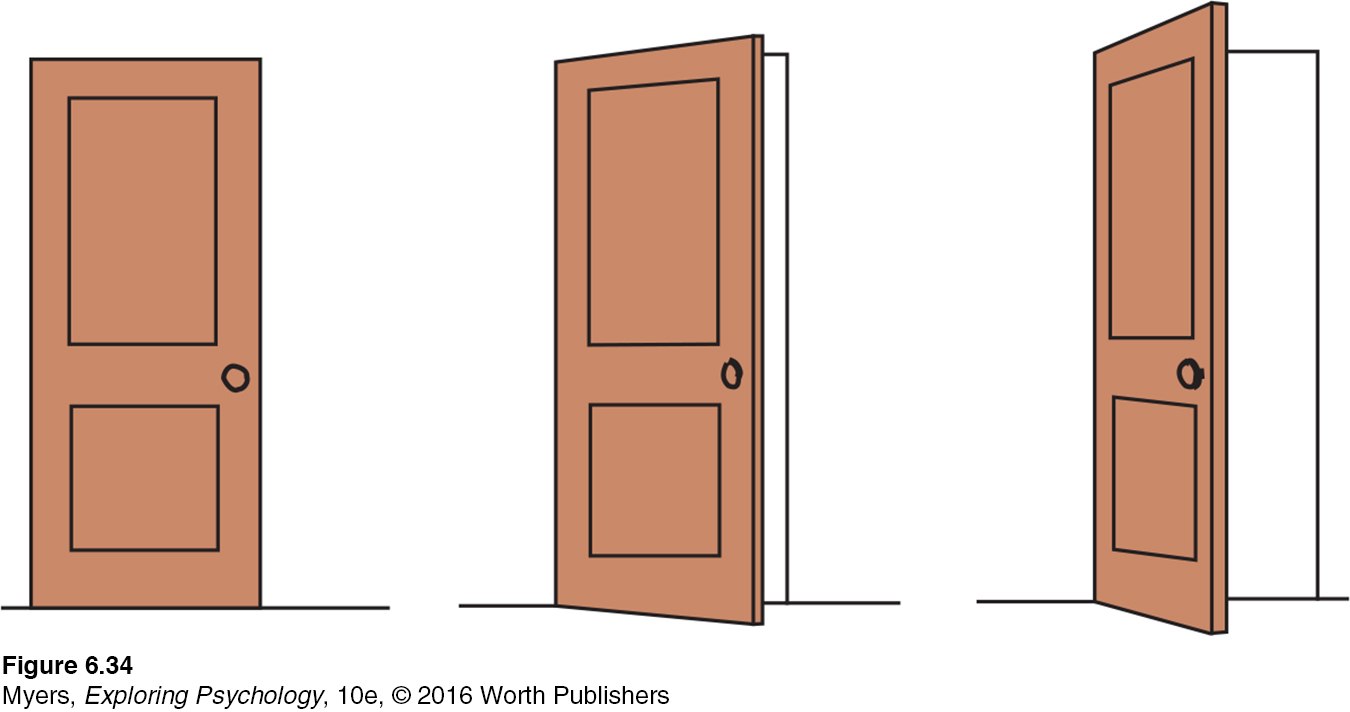

SHAPE AND SIZE CONSTANCIES Sometimes an object whose actual shape cannot change seems to change shape with the angle of our view (FIGURE 6.33). More often, thanks to shape constancy, we perceive the form of familiar objects, such as the door in FIGURE 6.34, as constant even while our retinas receive changing images of them. Our brain manages this feat thanks to visual cortex neurons that rapidly learn to associate different views of an object (Li & DiCarlo, 2008).

Thanks to size constancy, we perceive objects as having a constant size, even while our distance from them varies. We assume a car is large enough to carry people, even when we see its tiny image from two blocks away. This assumption also illustrates the close connection between perceived distance and perceived size. Perceiving an object’s distance gives us cues to its size. Likewise, knowing its general size—

Even in size-

For at least 22 centuries, scholars have wondered (Hershenson, 1989). One reason is that monocular cues to objects’ distances make the horizon Moon appear farther away. If it’s farther away, our brain assumes, it must be larger than the Moon high in the night sky (Kaufman & Kaufman, 2000). Take away the distance cue, by looking at the horizon Moon through a paper tube, and the object will immediately shrink.

Perceptual illusions reinforce a fundamental lesson: Perception is not merely a projection of the world onto our brain. Rather, our sensations are disassembled into information bits that our brain then reassembles into its own functional model of the external world. During this reassembly process, our assumptions—

* * *

Form perception, depth perception, and perceptual constancies illuminate how we organize our visual experiences. Perceptual organization applies to our other senses, too. Listening to an unfamiliar language, we have trouble hearing where one word stops and the next one begins. Listening to our own language, we automatically hear distinct words. This, too, reflects perceptual organization. But it is more, for we even organize a string of letters—

Perceptual Interpretation

To experience more visual illusions, and to understand what they reveal about how you perceive the world, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Visual Illusions.

To experience more visual illusions, and to understand what they reveal about how you perceive the world, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Visual Illusions.

Philosophers have debated whether our perceptual abilities should be credited to our nature or our nurture. To what extent do we learn to perceive? German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724–

“Let us then suppose the mind to be, as we say, white paper void of all characters, without any ideas: How comes it to be furnished? … To this I answer, in one word, from EXPERIENCE.”

John Locke, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, 1690

Experience and Visual Perception

6-

RESTORED VISION AND SENSORY RESTRICTION Writing to John Locke, William Molyneux wondered whether “a man born blind, and now adult, taught by his touch to distinguish between a cube and a sphere” could, if made to see, visually distinguish the two. Locke’s answer was No, because the man would never have learned to see the difference.

Molyneux’s hypothetical case has since been put to the test with a few dozen adults who, though blind from birth, later gained sight (Gregory, 1978; Huber et al., 2015; von Senden, 1932). Most were born with cataracts—

Seeking to gain more control than is provided by clinical cases, researchers have outfitted infant kittens and monkeys with goggles through which they could see only diffuse, unpatterned light (Wiesel, 1982). After infancy, when the goggles were removed, these animals exhibited perceptual limitations much like those of humans born with cataracts. They could distinguish color and brightness, but not the form of a circle from that of a square. Their eyes had not degenerated; their retinas still relayed signals to their visual cortex. But lacking stimulation, the cortical cells had not developed normal connections. Thus, the animals remained functionally blind to shape. Experience guides, sustains, and maintains the brain’s neural organization that enables our perceptions.

In both humans and animals, similar sensory restrictions later in life do no permanent harm. When researchers cover the eye of an adult animal for several months, its vision will be unaffected after the eye patch is removed. When surgeons remove cataracts that develop during late adulthood, most people are thrilled at the return to normal vision.

The effect of sensory restriction on infant cats, monkeys, and humans suggests that for normal sensory and perceptual development there is a critical period—

perceptual adaptation the ability to adjust to changed sensory input, including an artificially displaced or even inverted visual field.

PERCEPTUAL ADAPTATION Given a new pair of glasses, we may feel slightly disoriented, even dizzy. Within a day or two, we adjust. Our perceptual adaptation to changed visual input makes the world seem normal again. But imagine a far more dramatic new pair of glasses—

Could you adapt to this distorted world? Not if you were a baby chicken. When fitted with such lenses, baby chicks continue to peck where food grains seem to be (Hess, 1956; Rossi, 1968). But we humans adapt to distorting lenses quickly. Within a few minutes your throws would again be accurate, your stride on target. Remove the lenses and you would experience an aftereffect: At first your throws would err in the opposite direction, sailing off to the right; but again, within minutes you would readapt.

Indeed, given an even more radical pair of glasses—

At first, when Stratton wanted to walk, he found himself searching for his feet, which were now “up.” Eating was nearly impossible. He became nauseated and depressed. But he persisted, and by the eighth day he could comfortably reach for an object in the right direction and walk without bumping into things. When Stratton finally removed the headgear, he readapted quickly.

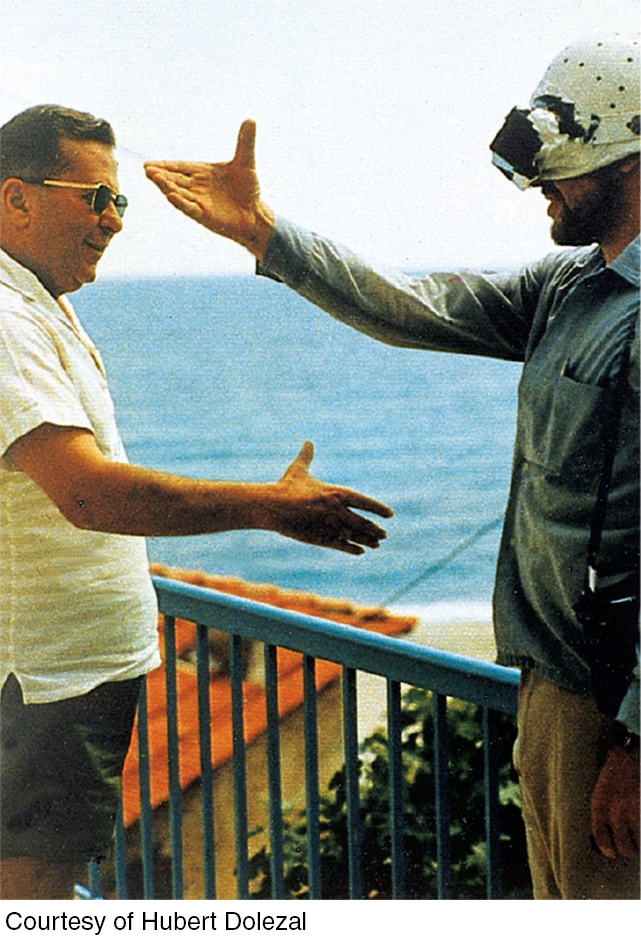

In later experiments, people wearing the optical gear have even been able to ride a motorcycle, ski the Alps, and fly an airplane (Dolezal, 1982; Kohler, 1962). The world around them still seemed above their heads or on the wrong side. But by actively moving about in these topsy-

Learning Objectives

Test Yourself by taking a moment to answer each of these Learning Objective Questions (repeated here from within the chapter). Research suggests that trying to answer these questions on your own will improve your long-

Question

6-

Question

6-

Question

6-

Question

6-

Question

6-

Question

6-

Question

6-

Question

6-

Question

6-

Terms and Concepts to Remember

Test yourself on these terms.

Question

wavelength (p. 209) hue (p. 209) intensity (p. 209) retina (p. 211) accommodation (p. 211) rods (p. 211) cones (p. 211) optic nerve (p. 211) blind spot (p. 211) fovea (p. 212) Young- opponent- feature detectors (p. 215) parallel processing (p. 216) gestalt (p. 217) figure- grouping (p. 217) depth perception (p. 218) visual cliff (p. 218) binocular cues (p. 219) retinal disparity (p. 219) monocular cues (p. 219) perceptual constancy (p. 221) color constancy (p. 221) perceptual adaptation (p. 223) | the theory that opposing retinal processes (red- an organized whole. Gestalt psychologists emphasized our tendency to integrate pieces of information into meaningful wholes. the point at which the optic nerve leaves the eye, creating a "blind" spot because no receptor cells are located there. the perceptual tendency to organize stimuli into coherent groups. a binocular cue for perceiving depth: By comparing images from the retinas in the two eyes, the brain computes distance- nerve cells in the brain that respond to specific features of the stimulus, such as shape, angle, or movement. depth cues, such as retinal disparity, that depend on the use of two eyes. the dimension of color that is determined by the wavelength of light; what we know as the color names blue, green, and so forth. the nerve that carries neural impulses from the eye to the brain. a laboratory device for testing depth perception in infants and young animals. perceiving familiar objects as having consistent color, even if changing illumination alters the wavelengths reflected by the objects. the ability to adjust to changed sensory input, including an artificially displaced or even inverted visual field. the ability to see objects in three dimensions although the images that strike the retina are two- perceiving objects as unchanging (having consistent color, brightness, shape, and size) even as illumination and retinal images change. the amount of energy in a light wave or sound wave, which influences what we perceive as brightness or loudness. Intensity is determined by the wave's amplitude (height). the distance from the peak of one light wave or sound wave to the peak of the next. Electromagnetic wavelengths vary from the short blips of cosmic rays to the long pulses of radio transmission. the light- the theory that the retina contains three different types of color receptors- the process by which the eye's lens changes shape to focus near or far objects on the retina. the processing of many aspects of a problem simultaneously; the brain's natural mode of information processing for many functions, including vision. the central focal point in the retina, around which the eye's cones cluster. retinal receptors that detect black, white, and gray, and are sensitive to movement; necessary for peripheral and twilight vision, when cones don't respond. retinal receptors that are concentrated near the center of the retina and that function in daylight or in well- the organization of the visual field into objects (the figures) that stand out from their surroundings (the ground). depth cues, such as interposition and linear perspective, available to either eye alone. |

Experience the Testing Effect

Test yourself repeatedly throughout your studies. This will not only help you figure out what you know and don’t know; the testing itself will help you learn and remember the information more effectively thanks to the testing effect.

Question 6.8

1. The characteristic of light that determines the color we experience, such as blue or green, is .

Question 6.9

2. The amplitude of a light wave determines our perception of

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 6.10

3. The blind spot in your retina is located where

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 6.11

4. Cones are the eye's receptor cells that are especially sensitive to ________ light and are responsible for our ________ vision.

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 6.12

5. Two theories together account for color vision. The Young-

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 6.13

6. What mental processes allow you to perceive a lemon as yellow?

Question 6.14

7. The cells in the visual cortex that respond to certain lines, edges, and angles are called .

Question 6.15

8. The brain's ability to process many aspects of an object or a problem simultaneously is called .

Question 6.16

9. Our tendencies to fill in the gaps and to perceive a pattern as continuous are two different examples of the organizing principle called

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 6.17

10. In listening to a concert, you attend to the solo instrument and perceive the orchestra as accompaniment. This illustrates the organizing principle of

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 6.18

11. The visual cliff experiments suggest that

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 6.19

12. Depth perception underlies our ability to

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 6.20

13. Two examples of depth cues are interposition and linear perspective.

Question 6.21

14. Perceiving a tomato as consistently red, despite lighting shifts, is an example of

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 6.22

15. After surgery to restore vision, patients who had been blind from birth had difficulty

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 6.23

16. In experiments, people have worn glasses that turned their visual fields upside down. After a period of adjustment, they learned to function quite well. This ability is called .

Use  to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in

to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in  .

.