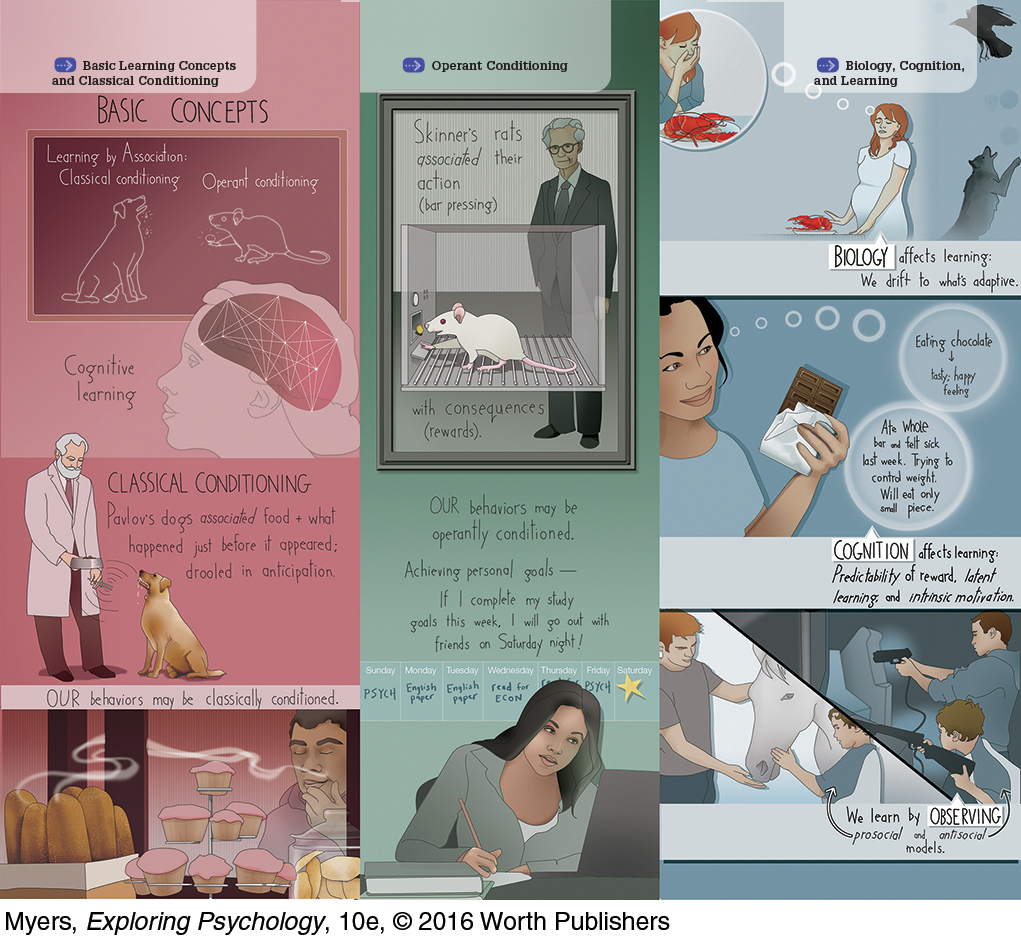

7.1 Basic Learning Concepts and Classical Conditioning

Learning

IN the early 1940s, University of Minnesota graduate students Marian Breland and Keller Breland witnessed the power of a new learning technology. Their mentor, B. F. Skinner, would become famous for shaping rat and pigeon behaviors by delivering well-

While writing about animal trainers, journalist Amy Sutherland wondered if shaping had uses closer to home (2006a, b). If baboons could be trained to skateboard and elephants to paint, might “the same techniques … work on that stubborn but lovable species, the American husband”? Step by step, she “began thanking Scott if he threw one dirty shirt into the hamper. If he threw in two, I’d kiss him [and] as he basked in my appreciation, the piles became smaller.” After two years of “thinking of my husband as an exotic animal species,” she reports, “my marriage is far smoother, my husband much easier to love.”

Like husbands and other animals, much of what we do we learn from experience. Indeed, nature’s most important gift may be our adaptability—

Learning breeds hope. What is learnable we can potentially teach—

No topic is closer to the heart of psychology than learning. In earlier chapters we considered infants’ learning, and the learning of visual perceptions, of a drug’s expected effect, and of gender roles. In later chapters we will see how learning shapes our thoughts and language, our motivations and emotions, our personalities and attitudes. Here in this chapter we examine classical conditioning, operant conditioning, the effects of biology and cognition on learning, and learning by observation.