8.2 Storing and Retrieving Memories

Memory Storage

8-

In Arthur Conan Doyle’s A Study in Scarlet, Sherlock Holmes offers a popular theory of memory capacity:

I consider that a man’s brain originally is like a little empty attic, and you have to stock it with such furniture as you choose. . . . It is a mistake to think that that little room has elastic walls and can distend to any extent. Depend upon it, there comes a time when for every addition of knowledge you forget something that you knew before.

Contrary to Holmes’ “memory model,” our brains are not like attics, which once filled can store more items only if we discard old ones. Our capacity for storing long-

Retaining Information in the Brain

I [DM] marveled at my aging mother-

For a time, some surgeons and memory researchers marveled at patients’ apparently vivid memories triggered by brain stimulation during surgery. Did this prove that our whole past, not just well-

The point to remember: Despite the brain’s vast storage capacity, we do not store information as libraries store their books, in single, precise locations. Instead, brain networks encode, store, and retrieve the information that forms our complex memories.

“Our memories are flexible and superimposable, a panoramic blackboard with an endless supply of chalk and erasers.”

Elizabeth Loftus and Katherine Ketcham, The Myth of Repressed Memory, 1994

EXPLICIT MEMORY SYSTEM: THE FRONTAL LOBES AND HIPPOCAMPUS

8-

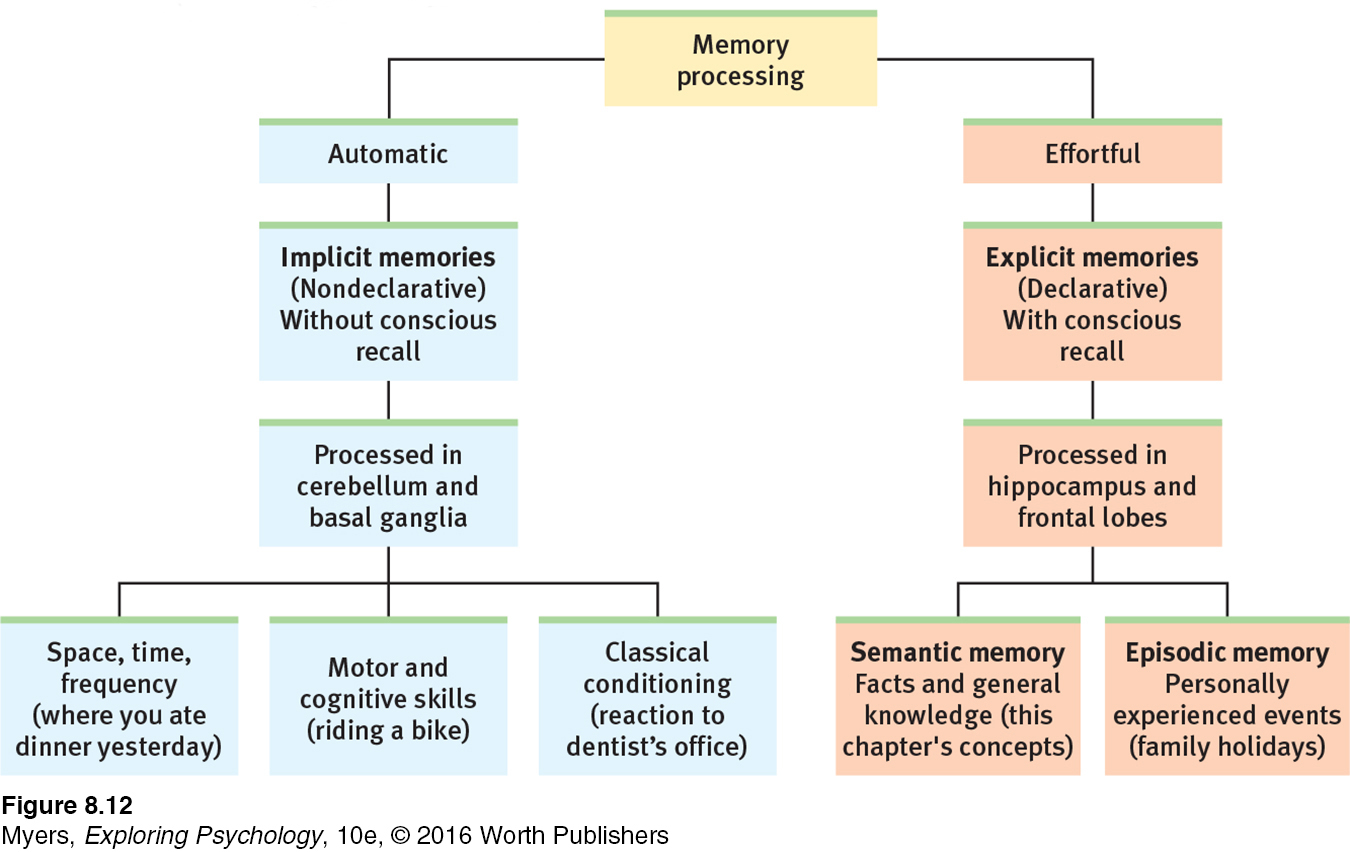

semantic memory explicit memory of facts and general knowledge; one of our two conscious memory systems (the other is episodic memory).

episodic memory explicit memory of personally experienced events; one of our two conscious memory systems (the other is semantic memory).

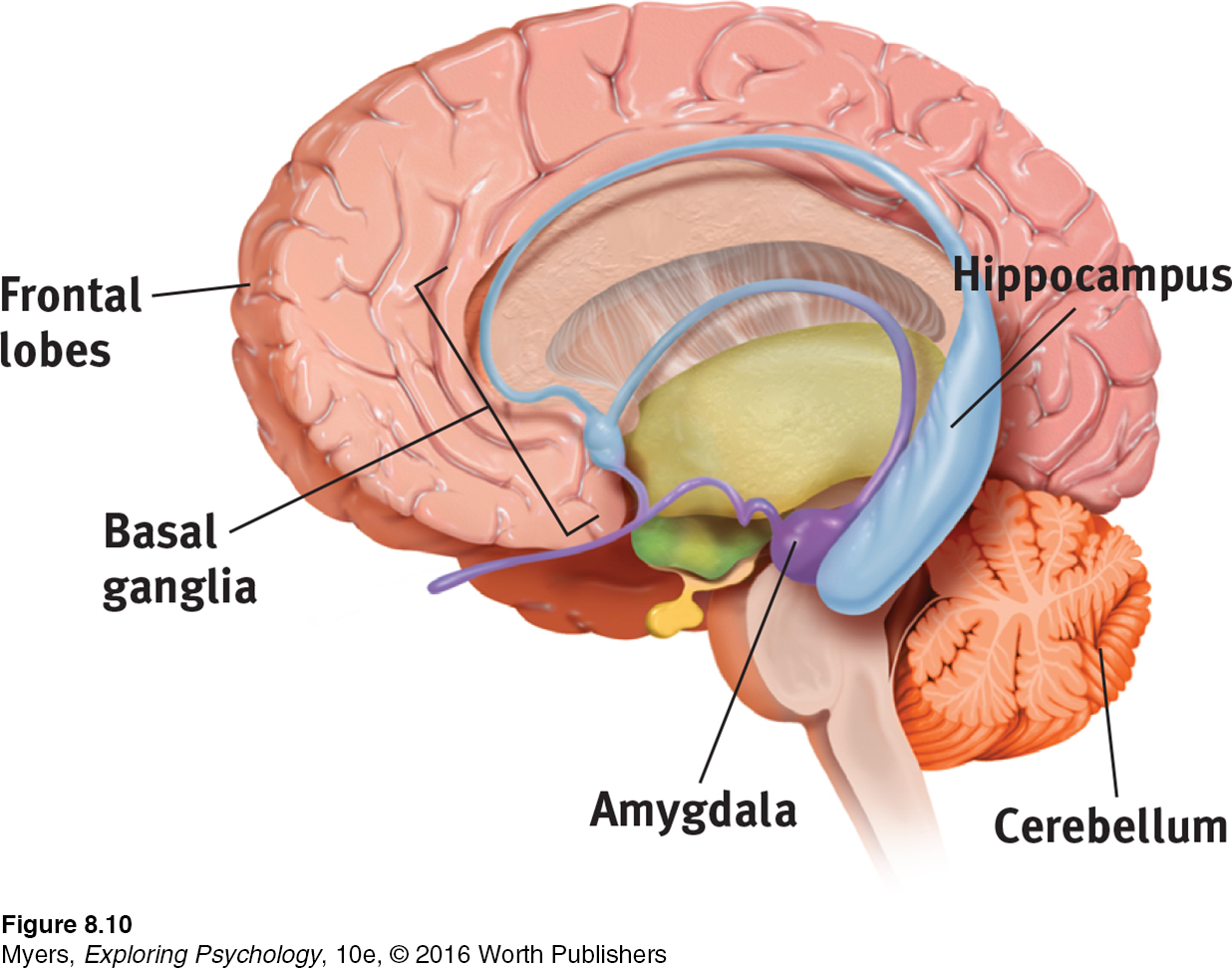

Explicit, conscious memories are either semantic (facts and general knowledge) or episodic (experienced events). The network that processes and stores your explicit memories for these facts and episodes includes your frontal lobes and hippocampus. When you summon up a mental encore of a past experience, many brain regions send input to your frontal lobes for working memory processing (Fink et al., 1996; Gabrieli et al., 1996; Markowitsch, 1995). The left and right frontal lobes process different types of memories. Recalling a password and holding it in working memory, for example, would activate the left frontal lobe. Calling up a visual party scene would more likely activate the right frontal lobe.

hippocampus a neural center located in the limbic system; helps process explicit memories for storage.

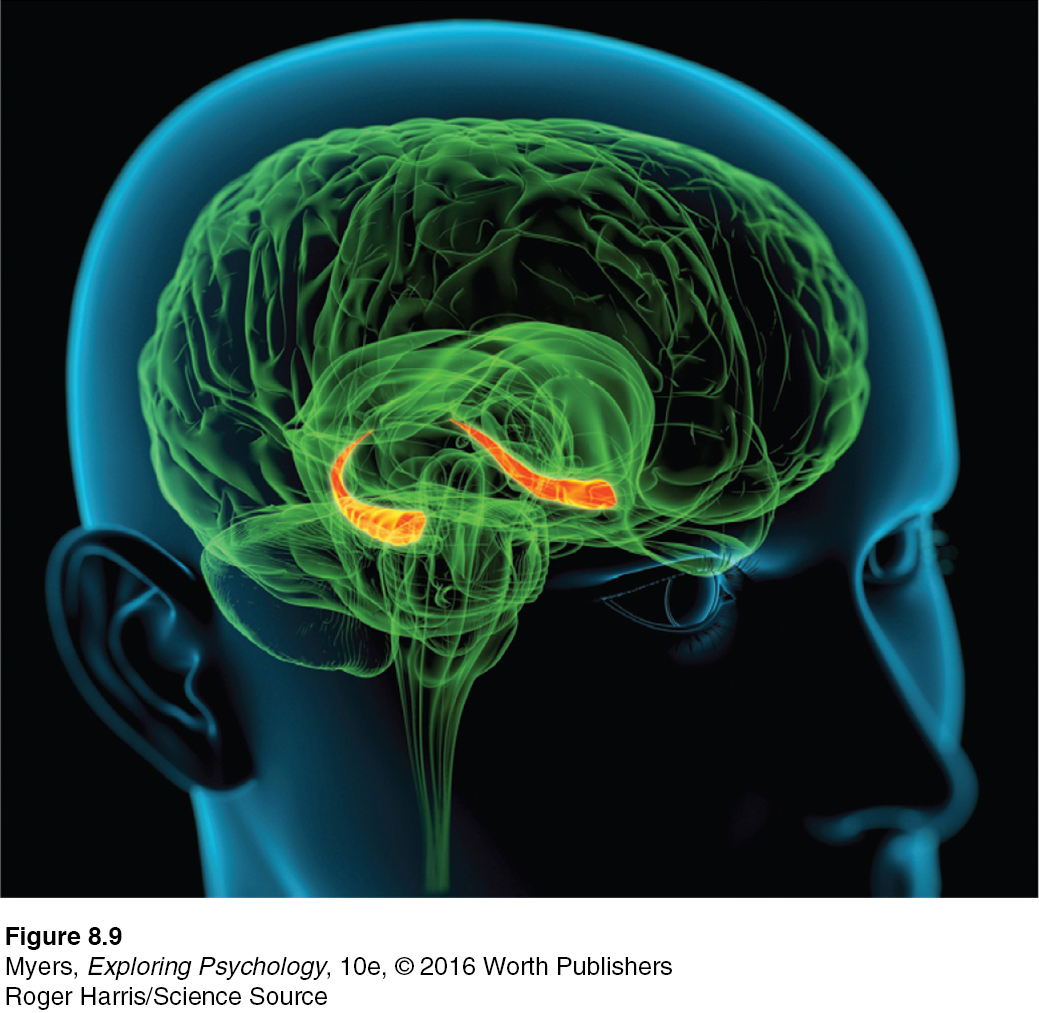

Cognitive neuroscientists have found that the hippocampus, a temporal-

Damage to this structure therefore disrupts recall of explicit memories. Chickadees and other birds can store food in hundreds of places and return to these unmarked caches months later—

Subregions of the hippocampus also serve different functions. One part is active as people learn to associate names with faces (Zeineh et al., 2003). Another part is active as memory champions engage in spatial mnemonics (Maguire et al., 2003b). The rear area, which processes spatial memory, grows bigger as London cabbies learn to navigate the city’s complicated maze of streets (Woolett & Maguire, 2011).

memory consolidation the neural storage of a long-

Memories are not permanently stored in the hippocampus. Instead, this structure seems to act as a loading dock where the brain registers and temporarily holds the elements of a remembered or retrieved episode—

Sleep supports memory consolidation. During deep sleep, the hippocampus processes memories for later retrieval. After a training experience, the greater the hippocampus activity during sleep, the better the next day’s memory will be (Peigneux et al., 2004). Researchers have watched the hippocampus and brain cortex displaying simultaneous activity rhythms during sleep, as if they were having a dialogue (Euston et al., 2007; Mehta, 2007). They suspect that the brain is replaying the day’s experiences as it transfers them to the cortex for long-

IMPLICIT MEMORY SYSTEM: THE CEREBELLUM AND BASAL GANGLIA

8-

Your hippocampus and frontal lobes are processing sites for your explicit memories. But you could lose those areas and still, thanks to automatic processing, lay down implicit memories for skills and newly conditioned associations. Joseph LeDoux (1996) recounted the story of a brain-

The cerebellum plays a key role in forming and storing the implicit memories created by classical conditioning. With a damaged cerebellum, people cannot develop certain conditioned reflexes, such as associating a tone with an impending puff of air—

The basal ganglia, deep brain structures involved in motor movement, facilitate formation of our procedural memories for skills (Mishkin, 1982; Mishkin et al., 1997). The basal ganglia receive input from the cortex but do not return the favor of sending information back to the cortex for conscious awareness of procedural learning. If you have learned how to ride a bike, thank your basal ganglia.

Our implicit memory system, enabled partly by these more ancient brain areas, helps explain why the reactions and skills we learned during infancy reach far into our future. Yet as adults, our conscious memory of our first three years is blank, an experience called infantile amnesia. In one study, events children experienced and discussed with their mothers at age 3 were 60 percent remembered at age 7 but only 34 percent remembered at age 9 (Bauer et al., 2007). Two influences contribute to infantile amnesia: First, we index much of our explicit memory using words that nonspeaking children have not learned. Second, the hippocampus is one of the last brain structures to mature, and as it does, more gets retained (Akers et al., 2014).

RETRIEVE IT

Question

Which parts of the brain are important for implicit memory processing, and which parts play a key role in explicit memory processing?

Question

Your friend has experienced brain damage in an accident. He can remember how to tie his shoes but has a hard time remembering anything you tell him during a conversation. What's going on here?

THE AMYGDALA, EMOTIONS, AND MEMORY

8-

Our emotions trigger stress hormones that influence memory formation. When we are excited or stressed, these hormones make more glucose energy available to fuel brain activity, signaling the brain that something important has happened. Moreover, stress hormones focus memory. Stress provokes the amygdala (two limbic system, emotion-

Significantly stressful events can form almost indelible memories. After traumatic experiences—

flashbulb memory a clear memory of an emotionally significant moment or event.

Emotion-

The people who experienced a 1989 San Francisco earthquake did just that. A year and a half later, they had perfect recall of where they had been and what they were doing (verified by their recorded thoughts within a day or two of the quake). Others’ memories for the circumstances under which they merely heard about the quake were more prone to errors (Neisser et al., 1991; Palmer et al., 1991).

Which is more important—

Our flashbulb memories are noteworthy for their vividness and our confidence in them. But as we relive, rehearse, and discuss them, these memories may come to err. With time, some errors crept into people’s 9/11 recollections (compared with their earlier reports taken right after 9/11). Mostly, however, people’s memories of 9/11 remained consistent over the next two to three years (Conway et al., 2009; Hirst et al., 2009; Kvavilashvili et al., 2009).

Dramatic experiences remain bright and clear in our memory in part because we rehearse them. We think about them and describe them to others. Memories of our best experiences, which we enjoy recalling and recounting, also endure (Storm & Jobe, 2012; Talarico & Moore, 2012). One study invited 1563 Boston Red Sox and New York Yankees fans to recall the baseball championship games between their two teams in 2003 (Yankees won) and 2004 (Red Sox won). Fans recalled much better the game their team won (Breslin & Safer, 2011).

Synaptic Changes

8-

As you read this chapter and think and learn about memory, your brain is changing. Given increased activity in particular pathways, neural interconnections are forming and strengthening.

The quest to understand the physical basis of memory—

long-term potentiation (LTP) an increase in a cell’s firing potential after brief, rapid stimulation. Believed to be a neural basis for learning and memory.

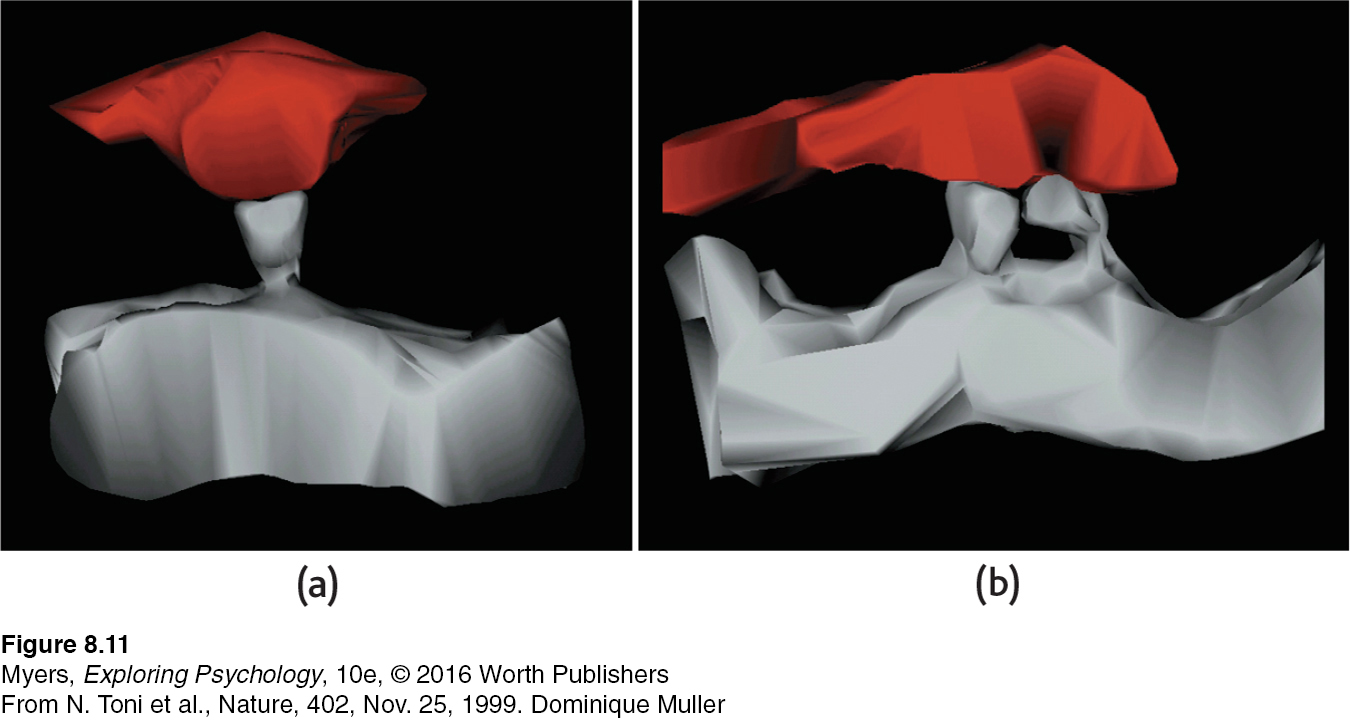

In experiments with people, rapidly stimulating certain memory-

Drugs that block LTP interfere with learning (Lynch & Staubli, 1991).

Mutant mice engineered to lack an enzyme needed for LTP couldn’t learn their way out of a maze (Silva et al., 1992).

Rats given a drug that enhanced LTP learned a maze with half the usual number of mistakes (Service, 1994).

After long-

Recently, I [DM] did a little test of memory consolidation. While on an operating table for a basketball-

Some memory-

Some of us may wish instead for memory-

FIGURE 8.12 summarizes the brain’s two-

RETRIEVE IT

Question

Which brain area responds to stress hormones by helping to create stronger memories?

Question

The neural basis for learning and memory, found at the synapses in the brain's memory-

Memory Retrieval

After the magic of brain encoding and storage, we still have the daunting task of retrieving the information. What triggers retrieval?

Retrieval Cues

8-

Imagine a spider suspended in the middle of her web, held up by the many strands extending outward from her in all directions to different points. If you were to trace a pathway to the spider, you would first need to create a path from one of these anchor points and then follow the strand down into the web.

“Memory is not like a container that gradually fills up; it is more like a tree growing hooks onto which memories are hung.”

Peter Russell, The Brain Book, 1979

The process of retrieving a memory follows a similar principle, because memories are held in storage by a web of associations, each piece of information interconnected with others. When you encode into memory a target piece of information, such as the name of the person sitting next to you in class, you associate with it other bits of information about your surroundings, mood, seating position, and so on. These bits can serve as retrieval cues that you can later use to access the information. The more retrieval cues you have, the better your chances of finding a route to the suspended memory.

For an 8-

For an 8-

The best retrieval cues come from associations we form at the time we encode a memory—

I knew I had been somewhere, and had done particular things with certain people, but where? I could not put the conversations . . . into a context. There was no background, no features against which to identify the place. Normally, the memories of people you have spoken to during the day are stored in frames which include the background.

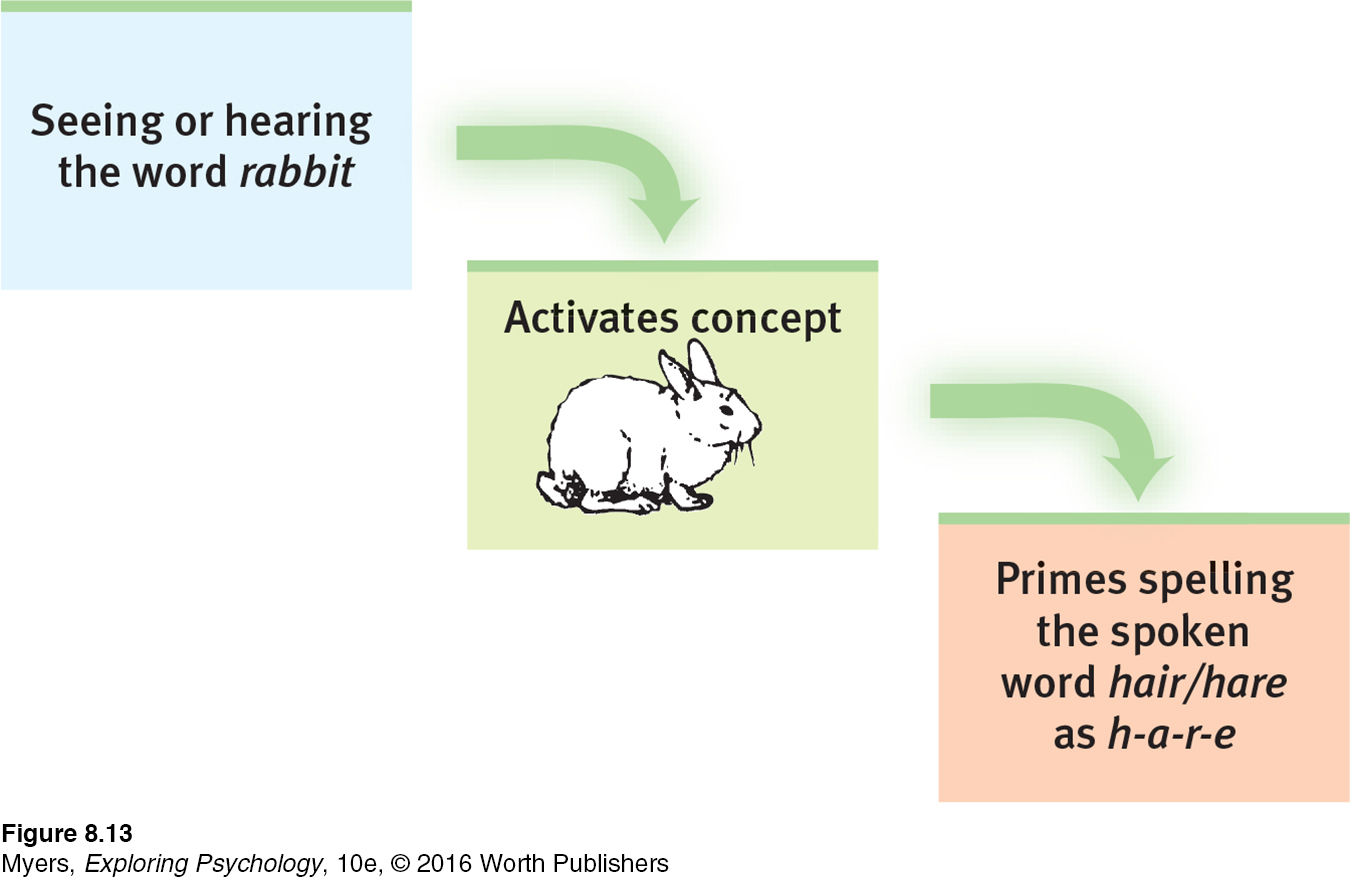

priming the activation, often unconsciously, of particular associations in memory.

PRIMING Often our associations are activated without our awareness. Philosopher-

Priming is often “memoryless memory”—invisible memory, without your conscious awareness. If, walking down a hallway, you see a poster of a missing child, you may then unconsciously be primed to interpret an ambiguous adult-

Priming can influence behaviors as well (Herring et al., 2013). In one study, participants primed with money-

Ask a friend two rapid-

CONTEXT-

By contrast, experiencing something outside the usual setting can be confusing. Have you ever run into your doctor in an unusual place, such as at the store or park? You knew the person but struggled to figure out who it was and how you were acquainted? Our memories depend on context, and on the cues we have associated with that context.

In several experiments, Carolyn Rovee-

STATE-

mood-congruent memory the tendency to recall experiences that are consistent with one’s current good or bad mood.

Our mood states provide an example of memory’s state dependence. Emotions that accompany good or bad events become retrieval cues (Gaddy & Ingram, 2014). Thus, our memories are somewhat mood congruent. If you’ve had a bad evening—

Knowing this mood-

“When a feeling was there, they felt as if it would never go; when it was gone, they felt as if it had never been; when it returned, they felt as if it had never gone.”

George MacDonald, What’s Mine’s Mine, 1886

Mood effects on retrieval help explain why our moods persist. When happy, we recall happy events and therefore see the world as a happy place, which helps prolong our good mood. When depressed, we recall sad events, which darkens our interpretations of current events. For those of us with a predisposition to depression, this process can help maintain a vicious, dark cycle. Moods magnify.

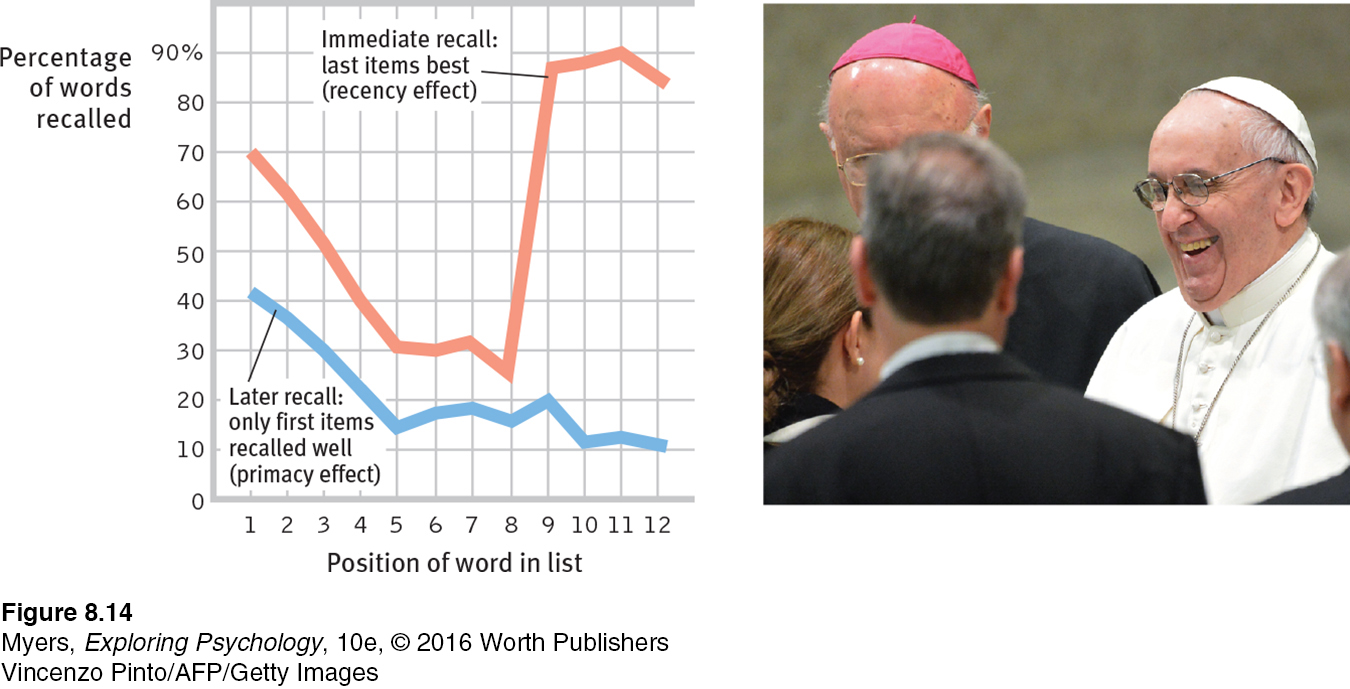

serial position effect our tendency to recall best the last (recency effect) and first (primacy effect) items in a list.

SERIAL POSITION EFFECT Another memory-

Don’t count on it. Because you have spent more time rehearsing the earlier names than the later ones, those are the names you’ll probably recall more easily the next day. In experiments, when people viewed a list of items (words, names, dates, even odors) and immediately tried to recall them in any order, they fell prey to the serial position effect (Reed, 2000). They briefly recalled the last items especially quickly and well (a recency effect), perhaps because those last items were still in working memory. But after a delay, when their attention was elsewhere, their recall was best for the first items (a primacy effect; see FIGURE 8.14).

RETRIEVE IT

Question

What is priming?

Question

When we are tested immediately after viewing a list of words, we tend to recall the first and last items best, which is known as the effect.

REVIEW Storing and Retrieving Memories

Learning Objectives

Test Yourself by taking a moment to answer each of these Learning Objective Questions (repeated here from within the chapter). Research suggests that trying to answer these questions on your own will improve your long-

Question

8-

Question

8-

Question

8-

Question

8-

Question

8-

Question

8-

Terms and Concepts to Remember

Test yourself on these terms.

Question

semantic memory (p. 292) episodic memory (p. 292) hippocampus (p. 293) memory consolidation (p. 293) flashbulb memory (p. 295) long- priming (p. 297) mood- serial position effect (p. 299) | the activation, often unconsciously, of particular associations in memory. a neural center located in the limbic system; helps process explicit memories for storage. the tendency to recall experiences that are consistent with one's current good or bad mood. an increase in a cell's firing potential after brief, rapid stimulation. Believed to be a neural basis for learning and memory. our tendency to recall best the last (recency effect) and first (primacy effect) items in a list. a clear memory of an emotionally significant moment or event. explicit memory of personally experienced events; one of our two conscious memory systems (the other is semantic memory). the neural storage of a long- explicit memory of facts and general knowledge; one of our two conscious memory systems (the other is episodic memory). |

Experience the Testing Effect

Test yourself repeatedly throughout your studies. This will not only help you figure out what you know and don’t know; the testing itself will help you learn and remember the information more effectively thanks to the testing effect.

Question 8.7

1. The hippocampus seems to function as a

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 8.8

2. Hippocampus damage typically leaves people unable to learn new facts or recall recent events. However, they may be able to learn new skills, such as riding a bicycle, which is an (explicit/implicit) memory.

Question 8.9

3. Long-term potentiation (LTP) refers to

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 8.10

4. Specific odors, visual images, emotions, or other associations that help us access a memory are examples of .

Question 8.11

5. When you feel sad, why might it help to look at pictures that reawaken some of your best memories?

Question 8.12

6. When tested immediately after viewing a list of words, people tend to recall the first and last items more readily than those in the middle. When retested after a delay, they are most likely to recall

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Use  to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in

to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in  .

.