Significant Differences

A-

Data are “noisy.” The average score in one group could conceivably differ from the average score in another group not because of any real difference but merely because of chance fluctuations in the people sampled. How confidently, then, can we infer that an observed difference is not just a fluke—

When Is an Observed Difference Reliable?

In deciding when it is safe to generalize from a sample, we should keep three principles in mind:

Representative samples are better than biased (unrepresentative) samples. The best basis for generalizing is from a representative sample of cases, not from the exceptional and memorable cases one finds at the extremes. Research never randomly samples the whole human population. Thus, it pays to keep in mind what population a study has sampled. (To see how an unrepresentative sample can lead you astray, see Thinking Critically About: Cross-

Sectional and Longitudinal Studies below.) Less-

variable observations are more reliable than those that are more variable . As we noted earlier in the example of the basketball player whose game-to- game points were consistent, an average is more reliable when it comes from scores with low variability. More cases are better than fewer cases. An eager prospective student visits two university campuses, each for a day. At the first, the student randomly attends two classes and discovers both instructors to be witty and engaging. At the next campus, the two sampled instructors seem dull and uninspiring. Returning home, the student (discounting the small sample size of only two teachers at each institution) tells friends about the “great teachers” at the first school, and the “bores” at the second. Again, we know it but we ignore it: Averages based on many cases are more reliable (less variable) than averages based on only a few cases.

The greater variability of small samples explains why small schools often are top producers of high-

The point to remember: Smart thinkers are not overly impressed by a few anecdotes. Generalizations based on a few unrepresentative cases are unreliable.

THINKING CRITICALLY ABOUT

Cross-

A-

When interpreting research results, smart thinkers consider how researchers arrived at their conclusions. One way studies vary is in the time period for gathering data.

cross-sectional study research in which people of different ages are compared with one another.

In cross-sectional studies, researchers compare different groups at the same time. When researchers compare intelligence test scores among people in differing age groups, older adults, on average, give fewer correct answers than do younger adults. This could suggest that mental ability declines with age, and indeed, that was the conclusion drawn from many early cross-

longitudinal study research in which the same people are restudied and retested over a long period of time.

In longitudinal studies, researchers study and restudy the same people at different times in their life span. Around 1920, colleges began giving intelligence tests to entering students, and several psychologists saw their chance to study intelligence longitudinally. What they expected to find was a decrease in intelligence after about age 30 (Schaie & Geiwitz, 1982). What they actually found was a surprise: Until late in life, intelligence remained stable. On some tests, it even increased.

Why did these new results differ from the earlier cross-

They were comparing

generally less-

educated people (born, say, in the early 1900s) with better- educated people (born after 1950). people raised in large families with people raised in smaller families.

people from less-

affluent families with people from more- affluent families.

Others have since pointed out that longitudinal studies have their own pitfalls. Participants who survive to the end of longitudinal studies may be the healthiest (and brightest) people. When researchers adjust for the loss of participants, as did one study following more than 2000 people over age 75 in Cambridge, England, they find a steeper intelligence decline, especially as people age after 85 (Brayne et al., 1999).

The point to remember: When interpreting research results, pay attention to the methodology used, such as whether it was a longitudinal or cross-

When Is an Observed Difference “Significant”?

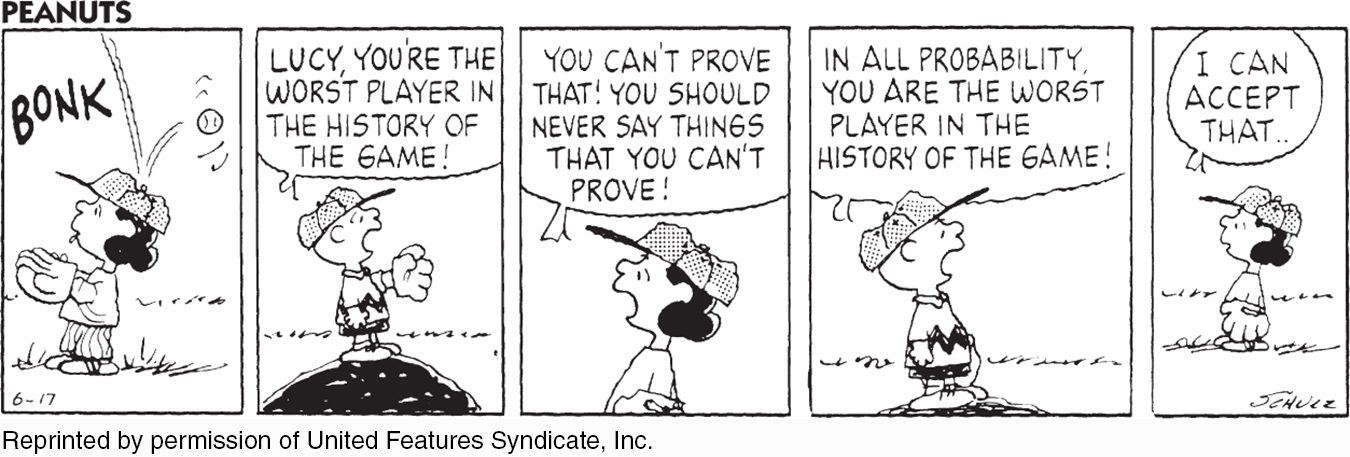

Perhaps you’ve compared men’s and women’s scores on a laboratory test of aggression, and you’ve found a gender difference. But individuals differ. How likely is it that the difference you observed was just a fluke? Statistical testing can estimate the probability of the result occurring by chance.

Here is the underlying logic: When averages from two samples are each reliable measures of their respective populations (as when each is based on many observations that have small variability), then their difference is probably reliable as well. (Example: The less the variability in women’s and in men’s aggression scores, the more confidence we would have that any observed gender difference is reliable.) And when the difference between the sample averages is large, we have even more confidence that the difference between them reflects a real difference in their populations.

statistical significance a statistical statement of how likely it is that an obtained result occurred by chance.

In short, when sample averages are reliable, and when the difference between them is relatively large, we say the difference has statistical significance. This means that the observed difference is probably not due to chance variation between the samples.

See LaunchPad’s Video: Longitudinal and Cross-

See LaunchPad’s Video: Longitudinal and Cross-

In judging statistical significance, psychologists are conservative. They are like juries who must presume innocence until guilt is proven. For most psychologists, proof beyond a reasonable doubt means not making much of a finding unless the odds of its occurring by chance, if no real effect exists, are less than 5 percent.

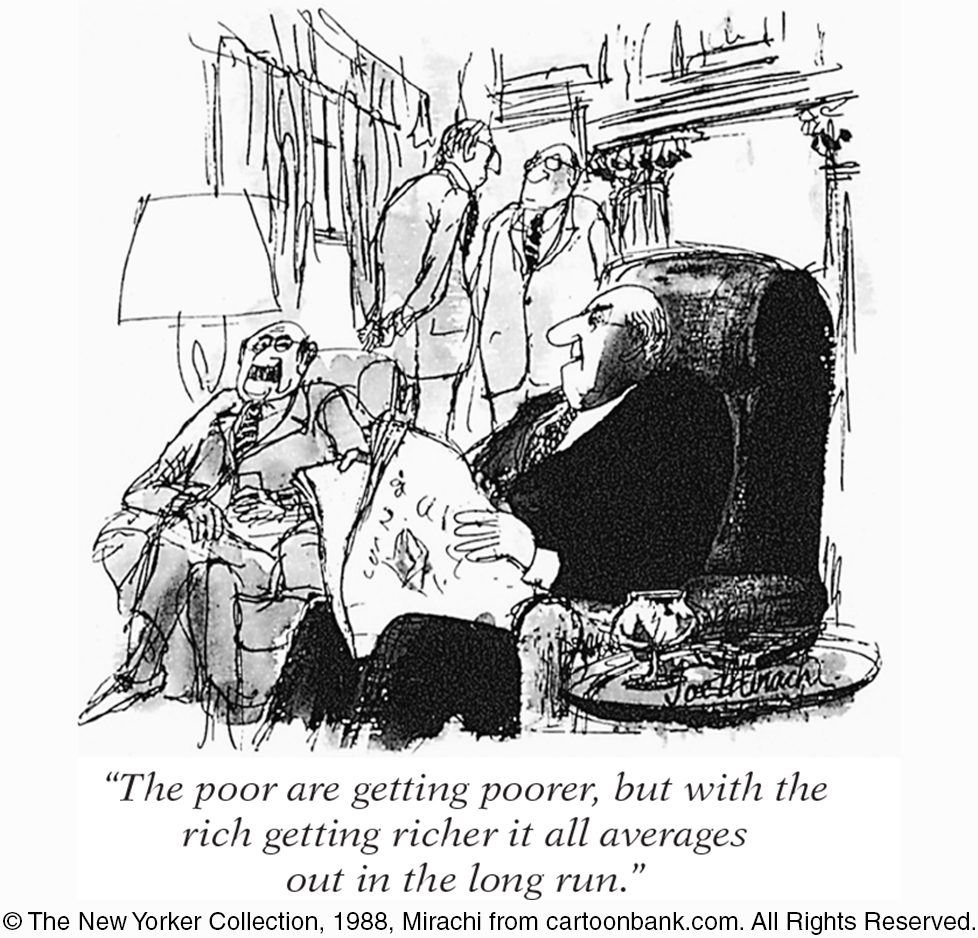

When reading about research, you should remember that, given large enough or homogeneous enough samples, a difference between them may be “statistically significant” yet have little practical significance. For example, comparisons of intelligence test scores among hundreds of thousands of first-

The point to remember: Statistical significance indicates the likelihood that a result will happen by chance. But this does not say anything about the importance of the result.

For a 9.5-

For a 9.5-

RETRIEVE IT

Can you solve this puzzle?

Question

The registrar's office at the University of Michigan has found that usually about 100 students in Arts and Sciences have perfect marks at the end of their first term at the University. However, only about 10 to 15 students graduate with perfect marks. What do you think is the most likely explanation for the fact that there are more perfect marks after one term than at graduation (Jepson et al., 1983)?

Question

statistics summarize data, while statistics determine if data can be generalized to other populations.

REVIEW Statistical Reasoning in Everyday Life

Learning Objectives

Test Yourself by taking a moment to answer each of these Learning Objective Questions (repeated here from within Appendix A). Research suggests that trying to answer these questions on your own will improve your long-

Question

A-

Question

A-

Question

A-

Question

A-

Question

A-

Terms and Concepts to Remember

Test yourself on these terms.

Question

mode (p. A- mean (p. A- median (p. A- range (p. A- standard deviation (p. A- normal curve (p. A- correlation coefficient (p. A- scatterplot (p. A- regression toward the mean (p. A- statistical significance (p. A- cross- longitudinal study (p. A- | a graphed cluster of dots, each of which represents the values of two variables. The slope of the points suggests the direction of the relationship between the two variables. The amount of scatter suggests the strength of the correlation (little scatter indicates high correlation). the arithmetic average of a distribution, obtained by adding the scores and then dividing by the number of scores. a study in which people of different ages are compared with one another. the middle score in a distribution; half the scores are above it and half are below it. research in which the same people are restudied and retested over a long period. the most frequently occurring score(s) in a distribution. the difference between the highest and lowest scores in a distribution. a computed measure of how much scores vary around the mean score. a statistical statement of how likely it is that an obtained result occurred by chance. a statistical index of the relationship between two things (from –1.00 to +1.00). (normal distribution) a symmetrical, bell- the tendency for extreme or unusual scores or events to fall back (regress) toward the average. |

Experience the Testing Effect

Test yourself repeatedly throughout your studies. This will not only help you figure out what you know and don’t know; the testing itself will help you learn and remember the information more effectively thanks to the testing effect.

Question 16.1

1. Which of the three measures of central tendency is most easily distorted by a few very large or very small scores?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 16.2

2. The standard deviation is the most useful measure of variation in a set of data because it tells us

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 16.3

3. Another name for a bell-

Question 16.4

4. In a ________ correlation, the scores rise and fall together; in a(n) ________ correlation, one score falls and the other rises.

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 16.5

5. If a study revealed that tall people were less intelligent than short people, this would suggest that the correlation between height and intelligence is (positive/negative).

Question 16.6

6. A provides a visual representation of the direction and the strength of a relationship between two variables.

Question 16.7

7. What is regression toward the mean, and how can it influence our interpretation of events?

Question 16.8

8. In studies, a characteristic is assessed across different age groups at the same time.

Question 16.9

9. When sample averages are ________ and the difference between them is ________, we can say the difference has statistical significance.

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Use  to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in

to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in  .

.